Jews, Cross the Dniester!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Me Israel Aestra JULU 3-QUGUSU 8 1979 Me Israel Assam Founoed Bu A.Z

me Israel Aestra JULU 3-QUGUSU 8 1979 me Israel Assam FOunoeD bu a.z. ppopes JULU 3-aUGUSB 8 1979 Member of the European Association of Music Festivals Executive Committee: Asher Ben-Natan, Chairman Honorary Presidium: ZEVULUN HAMMER - Minister of Education and Culture Menahem Avidom GIDEON PATT - Minister of Industry, Trade and Tourism Gary Bertini TEDDY KOLLEK - Mayor of Jerusalem Jacob Bistritzky Gideon Paz SHLOMO LAHAT - Mayor of Tel Aviv-Yafo Leah Porath Ya'acov Mishori Jacob Steinberger J. Bistritzky Director, the Israel Festival. Director, The Arthur Rubinstein International Piano Master Competition. Thirty years of professional activity in Artistic Advisor — Prof. Gary Bertini the field of culture and arts, as Director of the Department of International The Public Committee and Council: Cultural Relations in the Ministry of Gershon Achituv Culture and Arts, Warsaw; Director of the Menahem Avidom Polish Cultural Institute, Budapest: Yitzhak Avni Director of the Frédéric Chopin Institute, Warsaw. Mr. Bistritzky's work has Mordechai Bar On encompassed all aspects of the Asher Ben-Natan Finance Committee: development of culture, the arts and mass Gary Bertini Menahem Avidom, Chairman media: promotion, organization and Jacob Bistritzky Yigal Shaham management of international festivals and Abe Cohen Micha Tal competitions. Organizer of Chopin Sacha Daphna competitions in Warsaw and International Meir de-Shalit Chopin year 1960 under auspices of Walter Eytan Festival Staff: U.N.E.S.C.O. Shmuel Federmann Assistant Director: Ilana Parnes Yehuda Fickler Director of Finance: Isaac Levinbuk Daniel Gelmond Secretariat: Rivka Bar-Nahor, Paula Gluck Dr. Reuven Hecht Public Relations: Irit Mitelpunkt Dr. Paul J. -

What's on in Tel Aviv / January

WHAT'S ON IN TEL AVIV / JANUARY MUSIC EVENTS ECHOES PINK FLOYD MAD PROFESSOR SATYRICON 04 LIVE TRIBUTE SHOW 12 AND GAUDI 24 Barby Club Reading 3 Barby Club LED ZEPPELIN 2 – MAURICE EL MEDIONI MANOLIA 07 THE LIVE EXPERIENCE 12 AND NETA ELKAYAM 24 GREEK HITS 08 Bronfman Auditorium Einav Culture Center Suzanne Dellal Center SWING AND RAY GELATO CHRONOS PROJECT THE KOOKS 11 JAZZ CONCERT 15 BY DIMITRA GALANI 27 Barby Club 12 Tel Aviv Museum of Art Tel Aviv Museum of Art 28 MAIN CLASSICAL DANCE 1-4 THE RACE TO THE VIENNA BALL 5-6 THE YOUNG ENSEMBLE, BATSHEVA Strauss, Brahms, Smetana and Dvorak DANCE COMPANY - KAMUYOT Tel Aviv Performing Arts Center Suzanne Dellal Center 5-6 INBAL PINTO AND AVSHALOM POLLAK - OYSTER Suzanne Dellal Center THINGS TO DO FOR FREE ANTIQUE & SECOND HAND ITEMS FAIR Every Tuesday at 10 AM-6 PM and every Friday at 7 AM-4 PM 9 CHRIS ROCK STAND UP SHOW Givon Square Menora Mivtachim Arena TEL AVIV PORT TOUR 19-20 VERTIGO DANCE COMPANY AND Every Thursday at 11 AM REVOLUTION ORCHESTRA - WHITE NOISE Meeting point: Aroma Cafe, 1 Yordei HaSira Tel Aviv Performing Arts Center St. Hangar 9, Tel Aviv Port 4-17 A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM DESIGNERS & FOOD MARKET Opera Every Thursday and Friday, Tel Aviv Performing Arts Center FOR KIDS Dizengoff Center 5 CHRISTMAS VIENNESE BALL 6 BUTTERFLIES IN THE STOMACH TETRIS GAME ON THE St. Nicolas Monastery, Old Jaffa Mediatek, Holon• CITY HALL BUILDING 6 UPSTAIRS DOWNSTAIRS 13 ALICE IN WONDERLAND Every Thursday evening - Rabin Square* DANGEROUS LIAISONS IN MOZART’S OPERAS Circus Y, Circus Tent, Ramat Gan Stadium• SARONA TOUR Tel Aviv Performing Arts Center 13,27 GULLIVER (PLAY) Every Friday at 11 AM 16 BACH – BERNSTEIN Gesher Theatre Meeting point: Sarona Visitor’s Center, 11 Avraham Albert Mendler St. -

Double Anniversary for the Israeli-American Maestro of the Ruhr Region Steven Sloane's Projects and Concerts in the 2019/20 Season

Double anniversary for the Israeli-American maestro of the Ruhr region Steven Sloane's projects and concerts in the 2019/20 season General Music Director in Bochum for 25 years and the 100th birthday of his orchestra – 2019 is a very special year for Steven Sloane and his audience. The orchestra's anniversary year has been bookended at the start of the 19/20 season by a Ruhrtriennale production of a new music-theatre work by Kornél Mundruczó, and the regional capital of the Ruhr area also has some surprises in store in the symphonic realm. A second music-theatre highlight will follow in the spring with the first German performance of David Lang's “Prisoner of the State,” of which Sloane will give more national premières in Rotterdam, Bruges, Barcelona and Malmö. At the Swedish opera house, he will also be in charge of the new production of Puccini's “Tosca” from December as Principal Guest Conductor. In addition, as the Music Director Designate of the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra, Sloane will already be presenting three programmes with his new orchestra. These days, you'd need to search for a long time to find a General Music Director who has held this position in the same location for a quarter of a century while instigating the kind of thoroughgoing changes that Steven Sloane has in Bochum, displaying a constant innovative energy both artistically and in the field of cultural policy. Since he took up his position in the heart of the Ruhr area in 1994, he has turned the Bochumer Symphoniker (BoSy for short) into one of the top German orchestras. -

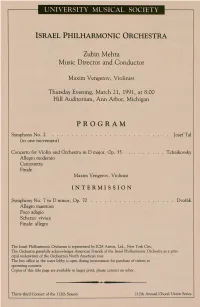

Israel Philharmonic Orchestra Program

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY ISRAEL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA Zubin Mehta Music Director and Conductor Maxim Vengerov, Violinist Thursday Evening, March 21, 1991, at 8:00 Hill Auditorium, Ann Arbor, Michigan PROGRAM Symphony No. 2 ......................... Josef Tal (in one movement) Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in D major, Op. 35 ........ Tchaikovsky Allegro moderate Canzonetta Finale Maxim Vengerov, Violinist INTERMISSION Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70 .................. DvoMk Allegro maestoso Poco adagio Scherzo: vivace Finale: allegro The Israel Philharmonic Orchestra is represented by ICM Artists, Ltd., New York City. The Orchestra gratefully acknowledges American Friends of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra as a prin cipal underwriter of the Orchestra's North American tour. The box office in the outer lobby is open during intermission for purchase of tickets to upcoming concerts. Copies of this title page are available in larger print; please contact an usher. Thirty-third Concert of the 112th Season 112th Annual Choral Union Series Program Notes Symphony No. 2 transparent figures. The episodes that follow JOSEF TAL (b.1910) are in the same vein, based either upon Honoring the composer's 80th birthday linear, melodic formulation or, as in the last he Polish-born Israeli composer episode, upon strong rhythmic patterns. The Josef Tal was born September 18, work comes to its climax in the last episode, 1910, near Poznan. After study in which all the previously heard elements ing at the Hochschule fur Musik participate. After this, there is a more sub in Berlin, he emigrated to Pales dued atmosphere and, towards the conclu tineT in 1934 and taught composition and sion, the full twelve-tone-row is heard in a piano at the Jerusalem Academy of Music, melodic presentation." serving as its director from 1948 to 1952. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 77, 1957-1958

SEVENTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1957-195 8 Boston Symphony Orchestra CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor C ON CE RT BULLETIN with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk Copyright, 1958, by Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot President Jacob J. Kaplan Vice-President Richard C. Paine Treasurer Talcott M. Banks E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Theodore P. Ferris Michael T. Kelleher Alvan T. Fuller Palfrey Perkins Francis W. Hatch Charles H. Stockton Harold D. Hodgkinson Raymond S. Wilkins C. D. Jackson Oliver Wolcott TRUSTEES EMERITUS Philip R. Allen M. A. DeWolfe Howe N. Penrose Hallowell Lewis Perry Edward A. Taft Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager Norman S. Shirk James J. Brosnahan Assistant Manager Business Administrator Leonard Burkat Rosario Mazzeo Music Administrator Personnel Manager SYMPHONY HALL BOSTON 15 [833] The LIVING TRUST The Living Trust is a Trust which you establish during your lifetime ... as part of your overall estate plan . and for the purpose of obtaining experienced management for a specified portion of your property ... as a protection to you and your family during the years ahead. May we discuss the benefits of a Living Trust with you and your attorney? Write or call THE PERSONAL TRUST DEPARTMENT The "N&tional Shawmut Bank of 'Boston Tel. LAfayette 3-6800 Member F.D.I.C. [834] SYMPHONIANA Exhibition Marcel Mule Reports from Israel EXHIBITION SHe %>usseau7/bttse ofjdoston An exhibition of paintings from the deCordova and Dana Museum of Lin- coln, Massachusetts is now on view in the Gallery. &>. v< .*>**$ • • o>r<^«-~ MARCEL MULE Marcel Mule was born in Aube (Orne) in 1901, studied both piano and violin, but in addition he learned to play the saxophone under the instruc- tion of his father, himself a virtuoso. -

EDVARD GRIEG Complete Symphonic Works • Vol. 1

EDVARD GRIEG Complete Symphonic Works Vol. 1 • Symphonic Dances, Op. 64 • Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46 incidental music to Peer Gynt by Ibsen • Peer Gynt Suite No. 2, Op. 55 incidental music to Peer Gynt by Ibsen • funeral March in Memory of Rikard Nordraak EG 107 WDR SINfONIEORCHESTER KöLN EIVIND AADLAND, conductor recording date: Oktober 2010 Philharmonie, Köln release date: 24 June 2011 »audite« Ludger Böckenhoff • Tel.: +49 (0) 52 31-870 320 • Fax: +49 (0) 52 31-870 321 • [email protected] • www.audite.de EDVARD GRIeg Complete Symphonic Works Vol. II • Two Elegiac Melodies, Op. 34 • Holberg Suite, Op. 40 • Two Melodies, Op. 53 • Two Nordic Melodies, Op. 63 recording date: August / September 2009 relese date: August 2011 audite 92.579 (SACD / digipac) Vol. III • Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 • Old Norwegian Romance with Variations for orchestra, Op. 51 • Lyric Suite for Orchestra, Op. 54 • “Glockengeläute” recording date: September 2011 / February 2012 audite 92.669 (SACD / digipac) Vol. IV • “I host“ (In Autumn), concert overture for orchestra, Op. 11 • Six Orchestral Songs • Two Lyric Pieces • “Der Bergentrückte“ • Three Orchestral Pieces from Sigurd Jorsalfar, Op.56 audite 92.670 (SACD / digipac) Vol. V • Symphony No. 1 • Norwegian Dances • “Vor der Klosterpforte“ • etc. audite 92.671 (SACD / digipac) WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln Eivind Aadland, conductor »audite« Ludger Böckenhoff • Tel.: +49 (0) 52 31-870 320 • Fax: +49 (0) 52 31-870 321 • [email protected] • www.audite.de PLAYS ON ALL CD- AND SACD- PLAYERS! MUSIKPRODUKTION Press Info: EDVARD GRIEG Complete Symphonic Works • Vol. I • Symphonic Dances, Op. -

Robert Schumann Vol. Ii

ROBERT SCHUMANN Complete Symphonic Works VOL. II HEINZ HOLLIGER WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln ROBERT SCHUMANN Complete Symphonic Works • Vol. II recording date: January 23-27, 2012 (Symphony No. 2) March 19-23, 2012 (Symphony No. 3) Symphony No. 2 in C major, Op. 61 36:10 I. Sostenuto assai – Allegro ma non troppo 12:01 P Eine Produktion des Westdeutschen Rundfunks Köln, 2012 II. Scherzo. Allegro vivace 7:03 lizenziert durch die WDR mediagroup GmbH III. Adagio espressivo 8:26 recording location: Köln, Philharmonie IV. Allegro molto vivace 8:40 executive producer (WDR): Siegwald Bütow recording producer & editing: Günther Wollersheim recording engineer: Brigitte Angerhausen Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 97 ‘Rhenish’ 30:35 Recording assistant: Astrid Großmann I. Lebhaft 8:58 photos: Heinz Holliger (page 8): Julieta Schildknecht II. Scherzo. Sehr mäßig 5:40 WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln (page 5): WDR Thomas Kost III. Nicht schnell 5:08 WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln (page 9): Mischa Salevic IV. Feierlich 5:04 front illustration: ‘Sonnenuntergang (Brüder)’ Caspar David Friedrich V. Lebhaft 5:45 art direction and design: AB•Design executive producer (audite): Dipl.-Tonmeister Ludger Böckenhoff e-mail: [email protected] • http: //www.audite.de HEINZ HOLLIGER © 2014 Ludger Böckenhoff WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln Robert Schumann‘s instrumental sound – the sound towards The C-major Symphony not only sketched, but also developed. Symphonies which Brahms and Franck also strove” He also spent more time revising works, A peculiar contradiction has marked the (Jon W. Finson). He attained it, above all, If one were to count Schumann’s Sym- both during their preparatory stages and reception of Schumann’s symphonies. -

Odessa Soundscapes Одесса Мама Еврейская Музыка Mama of Odessa Одессы

Center for the Study of Cultures of Place in the מרכז לחקר המוסיקה היהודית Modern Jewish World JEWISH MUSIC RESEARCH CENTRE Supported by the I-CORE Program of the Planning and Budgeting Committee and The Israel Science Foundation (grant No 1798/12) אימא אודסה המוסיקה של אודסה Jewish היהודית Odessa Soundscapes Одесса Мама Еврейская Музыка Mama of Odessa Одессы Music of the Synagogue and the Jewish Street in Odessa at the Beginning of the 20th Century Sunday, 25 March 2018 Cantor Azi Schwartz (Park Avenue Synagogue, New York) Vira Lozinski - Yiddish and Russian songs The Chamber Choir of the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance Conductor: Stanley Sperber Piano and organ: Raymond Goldstein Da'at Hamakom - Center for the Study of Cultures of Place in the Modern Jewish World Jewish Music Research Centre - Faculty of the Humanities - The Hebrew University of Jerusalem In collaboration with Park Avenue Synagogue, New York Idea and production: Anat Rubinstein, Eliyahu Schleifer, Edwin Seroussi (Jewish Music Research Centre) Technical support and production coordination: Anat Reches (Da'at Hamakom), Sari Salis, Tali Schach (Jewish Music Research Centre) Production coordination for the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance: Chana Englard The Chamber Choir of the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance Conductor and musical manager: Stanley Sperber Assistant conductor: Taum Karni Musical adviser: Tami Kleinhaus Choir pianist: Irina Lunkevitch Choir manager: Maya Politzer Acting choir manager: Yif'at Shachar Choir members: Soprano Alto Tenor Bass Maria -

The Opera: 'Ashmedi' by City Tro.Upe

THE NEW YORK TIMES, FRIDAY, APRIL 2, 1976 The Opera: 'Ashmedi' by City Tro.upe Work by Josef Tal Is The Cast It's A~other Devil of a ASHMEOAI, ooera ln lwo act br Joseoh Tal. Lobrette br Israel Eliraz; Engllsn at State Theater Iransialion br Alan ll.arbe, Concuct•d • Triumph Over Man by Gary Berlinl. Staged by Harold ------------ Printe. Sets de,i9nc<l by Euo~e Lee. Costumes dP.signed by Franne lP.P. By HAROLD C. SCHONBERG . Chorrograohod by Ron Fleld. Lighfino brilliant in characterization bv Ken Billinglon, Olrector ol electronic Add to your Iist of operas Sound, Eck.hard Marron. Ame-r.ran were Eileen Schauler as the with devils: "Ashmedei" by oremiere bt tne Ntw Vork City OPera Queen, Richard Taylor as the at lhe N;IY Vork State Theater. Josef Tal. lt was composed Ouetn .................. Eileen Schauler Prince, Gianni Rolandi ao:; the in 1971 and bad its American Mistre1i ot lnn ••....•... Patricia .Crai!;l Oaughl•; ................ Cianna Roland I Daughtcr and Patricia Craig premiere last night at the KinlJ •.•.•••••••••••••• , ••••. Paul Ukena New York ()tate Theater. Mr. Ashmodal ................ John Lanksion as the Mistress of the Inn. Son ..................... Richard TayiO<' Tal is an Israeli composer Tailor ..........••••....•... Jerold Siena Smaller roles were also well and is considered one of the First Counsellor .......... Oavld Gritiith handled. 2d Counsellor ........ Thoma; Jamerson avant-gardists there. But if lj Counsellor • , ........... Oavld Ronson Gary Bertini, tht> Israeli· this opera is .representative Exe-cutioner ...•....• , ...•. lrwin Oenst·l1 conductor, led the ._~rform Citlzen . • .. .. • .. • • . Don Vule or his work, his avant-garde Firsr Soldier ........... -

Oberlin Contemporary Music Ensemble

������ ������������������������ ������������������������������������� ��������������������� ���������������������������� ��������������������������������������� ����������������� �������������� ������������ �������������� ������������������������������������������������ ������������������������ ���������������������������������������� �������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ������������������������������� ������������������������������������������ ������������������ ������������������������������� ���������������� ������������������������ ������� �������������� ������������������������������� Oberlin Contemporary Music �������������������������� ���������������Ensemble ������������� ������������������������������������Timothy Weiss, conductor ����������������������������������������������������� ������������������Jonathan Moyer, organ �������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������� �������������������Yuri Popowycz, violin ��������������� ���������������� ������������������������������������ ����������������������������������������������������� ����������������������� ��������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������ -

International Piano Master Competition April 1977 Israel the Second

THE SECOND A’ & „,a^ J INTERNATIONAL PIANO MASTER COMPETITION APRIL 1977 ISRAEL THE SECOND INTERNATIONAL PANO MASTER COMPETITION APRIL 1977 ISRAEL HONORARY PRESIDENT: MAESTRO ARTHUR RUBINSTEIN a grand lady dedicated to a great man and a peerless artist HONORARY ’COMMITTEE GUIDO AGOSTI-Italy LAJOS HERNADI -Hungary HAIM ALEXANDER - Israel MIECZYSLAW HORSZOWSKI - U.S.A. Mr. & Mrs. AMIOT - France SOL HUROK - U.S.A. HERBERT ARMSTRONG - U.S.A. RENE HUYGHE - France CLAUDIO ARRAU - Chile EUGENE ISTOMIN - U.S.A. GOLDA MEIR-Chairman ERNEST J. JAFET VLADIMIR ASHKENAZY-Iceland JOSEPH KESSEL - France ASHER BEN—NATAN - Vice-Chairman THEODORE KOLLEK STEFAN ASKENASE - Belgium MOSHE KOL - Vice-Chairman YOCHEVED KOPERNIK-DOSTROVSKY GEORGES AURIC - France IRVING KOLODIN - U.S.A. MICHAEL SELA-Vice-Chairman SHLOMO LAHAT MENAHEM AVIDOM - Israel LORIN MAAZEL - U.S.A. AHARON YADLIN-Vice-Chairman ITZHAK LIVNI GINA BACHAUER - England NIKITA MAGALOFF - Switzerland HS. LOWENBERG DANIEL BARENBOIM - Israel FREDRIC R. MANN-U.S.A. SECOND YIGAL ALLON MOSHE MAYER A. BENEDETTI MICHELANGELI - Italy SIR ROBERT MAYER - England ITZHAK ARTZI BEN-ZION ORGAD ANDRE MARESCOTTI - Switzerland ARTHUR RUBINSTEIN PAUL BEN-HAIM ODEON PARTOS ASHER BEN-NATAN - Israel WILLIAM MAZER -U.S.A. INTERNATIONAL HAIM BEN—SHAHAR LEA PORATH DIANE BENVENUTI - France ZUBIN MEHTA-India GARY BERTINI YEHOSHUA RABINOWITZ LENNOX BERKELEY - England YEHUDI MENUHIN - England PIANO MASTER AVRAHAM ROZENMAN LEONARD BERNSTEIN -U.S.A. DARIUS MILHAUD - France THE INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION MOSHE SANBAR JACK BORNOFF - England SIR CLAUS MOSER - England WALTER EYTAN SH. SHALOM FOUNDERS' NADIA BOULANGER - France VICTOR NAJAR France SAMUEL FEDERMAN MICHAL SMOIRA—COHN MONIQUE DE LA BROUCHOLLERIE - f MARLOS NOBRE - Brazil BARUCH GROSS ARIE VARDI COMMITTEE MARQUESA OLGA DE CADAVAL - Pon EUGENE ORMANDY - U.S.A. -

Damen-Trio-Inglese2014.Pdf

DAMEN TRIO Stefania Bonfadelli Laura Polverelli soprano mezzo-soprano Nicoletta Olivieri piano Three female protagonists of the contemporary international opera scene join together in a refined and unique project to celebrate the art of chamber singing, with special attention to the role of women Three contemporary primedonne and a program of arias and duets composed by the most famous primedonne of the 19th Century Arias and duets by Angelica Catalani, Josephine Fodor Mainvielle, Maria Malibran, Caroline Ungher Sabatier, Isabella Colbran, Marietta Brambilla, Giuditta Pasta, Pauline Viardot e Adelina Patti Arias and duets by Angelica Catalani, Josephine Fodor Mainvielle, Maria Malibran, Caroline Ungher Sabatier, Isabella Colbran, Marietta Brambilla, Giuditta Pasta, Pauline Viardot e Adelina Patti Angelica Catalani (1780-1849) Variations on the aria “Nel cor piu’ non mi sento” Isabella Colbran (1785-1825) from PETITS AIRS ITALIENS: Benche’ tu sia crudel Vorrei che almen per gioco Per costume o mio bel nume T’intendo si’ mio cor Ch’io mai vi possa lasciar d’amare Josephine Fonder Mainvielle (1789-1870) Mes adieux a Naples Nell’alto della notte Giuditta Pasta (1797-1865) Invito alla campagna Caroline Ungher Sabatier (1803-1877) Nocturne Der Madchen Friedenslieder Stornello Toscano (duetto) Maria Malibran (1808-1836) Il Gondoliere (duetto) La Fiancée du brigand Addio a Nice La visita della Morte Rataplan tambour habile Marietta Brambilla (1807-1875) L’ora d’amore La Veneziana Salve o sterile pianura! La Capanna (duetto) Pauline Viardot Garcia (1821-1918) L’enfant de la montagne Évocation Deux Mazurkas: Aime moi, L’oiselet Les Bohémiennes (duetto) Adelina Patti (1843-1919) Speme Arcana Il bacio d ’Addio The program includes arias and duets composed in the XIX Century by the absolute female protagonists of operatic theatre.