ISSN 1060-1503 [Article] (Forthcoming)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

TRANSNATIONAL SMYTH: SUFFRAGE, COSMOPOLITANISM, NETWORKS Erica Fedor a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty at the University Of

TRANSNATIONAL SMYTH: SUFFRAGE, COSMOPOLITANISM, NETWORKS Erica Fedor A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Annegret Fauser David Garcia Tim Carter © 2018 Erica Fedor ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Erica Fedor: Transnational Smyth: Suffrage, Cosmopolitanism, Networks (Under the direction of Annegret Fauser) This thesis examines the transnational entanglements of Dame Ethel Smyth (1858–1944), which are exemplified through her travel and movement, her transnational networks, and her music’s global circulation. Smyth studied music in Leipzig, Germany, as a young woman; composed an opera (The Boatswain’s Mate) while living in Egypt; and even worked as a radiologist in France during the First World War. In order to achieve performances of her work, she drew upon a carefully-cultivated transnational network of influential women—her powerful “matrons.” While I acknowledge the sexism and misogyny Smyth encountered and battled throughout her life, I also wish to broaden the scholarly conversation surrounding Smyth to touch on the ways nationalism, mobility, and cosmopolitanism contribute to, and impact, a composer’s reputations and reception. Smyth herself acknowledges the particular double-bind she faced—that of being a woman and a composer with German musical training trying to break into the English music scene. Using Ethel Smyth as a case study, this thesis draws upon the composer’s writings, reviews of Smyth’s musical works, popular-press articles, and academic sources to examine broader themes regarding the ways nationality, transnationality, and locality intersect with issues of gender and institutionalized sexism. -

Disability and Music

th nd 19 November to 22 December UKDHM 2018 will focus on Disability and Music. We want to explore the links between the experience of disablement in a world where the barriers faced by people with impairments can be overwhelming. Yet the creative impulse, urge for self expression and the need to connect to our fellow human beings often ‘trumps’ the oppression we as disabled people have faced, do face and will face in the future. Each culture and sub-culture creates identity and defines itself by its music. ‘Music is the language of the soul. To express ourselves we have to be vibrating, radiating human beings!’ Alasdair Fraser. Born in Salford in 1952, polio survivor Alan Holdsworth goes by the stage name ‘Johnny Crescendo’. His music addresses civil rights, disability pride and social injustices, making him a crucial voice of the movement and one of the best-loved performers on the disability arts circuit. In 1990 and 1992, Alan co- organised Block Telethon, a high-profile media and community campaign which culminated in the demise of the televised fundraiser. His albums included Easy Money, Pride and Not Dead Yet, all of which celebrate disabled identity and critique disabling barriers and attitudes. He is best known for his song Choices and Rights, which became the anthem for the disabled people’s movement in Britain in the late 1980s and includes the powerful lyrics: Choices and Right That’s what we gotta fight for Choices and rights in our lives I don’t want your benefit I want dignity from where I sit I want choices and rights in our lives I don’t want you to speak for me I got my own autonomy I want choices and rights in our lives https://youtu.be/yU8344cQy5g?t=14 The polio virus attacked the nerves. -

Cyril Scott (1879 - 1970)

SRCD.365 STEREO/UHJ DDD The songs of Cyril Scott (1879 - 1970) 1 Pierrot and the Moon Maiden (1912) Dowson 3.01 2 Daffodils Op. 68 No. 1 (1909) Erskine 1.57 3 Spring Song (1913) C Scott 2.33 The songs of 4 Don't Come in Sir, Please! Op. 43 No. 2 (1905) trans. Giles 2.15 5 Willows Op. 24 No. 2 (1903) C Scott 2.21 Cyril Scott 6 In a Fairy Boat Op. 61 No. 2 (1908) Weller 2.05 7 Lovely Kind & Kindly Loving Op. 55 No. 1(1907) Breton 2.23 8 Scotch Lullabye Op. 57 No. 3 (1908) W Scott 3.37 9 The Watchman (1920) Hildyard 3.15 10 Water-Lilies (1920) O’Reilly 2.06 11 Voices of Vision Op. 24 No. 1 (1903) C Scott 4.42 12 Sundown (1919) Grenside 2.55 Charlotte de Rothschild 13 Autumn’s Lute (1914) R.M Watson 2.05 14 A Valediction Op. 36 No. 1 (1904) Dowson 2.21 Adrian Farmer 15 Lullaby Op. 57 No. 2 (1908) C Rossetti 2.25 Charlotte de Rothschild, soprano Adrian Farmer, piano c & © 2018 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Lyrita is a registered trade mark. Made in the UK LYRITA RECORDED EDITION. Produced under an exclusive licence from Lyrita by Wyastone Estate Ltd, PO Box 87, Monmouth, NP25 3WX, UK SRCD 365 16 SRCD 365 1 The Songs of Cyril Scott Cyril Scott(1879- 1970) A composer who writes songs arguably allows us into a very personal side of his or her character. An instrumental composition gives us access to a composer’s imagination 16 The Unforeseen Op. -

Rosaleen Norton's Contribution to The

ROSALEEN NORTON’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE WESTERN ESOTERIC TRADITION NEVILLE STUART DRURY M.A. (Hons) Macquarie University; B.A. University of Sydney; Dip. Ed. Sydney Teachers College Submission for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Science University of Newcastle NSW, Australia Date of submission: September 2008 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY This work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Signed: Date: Neville Stuart Drury ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP I hereby certify that the work embodied in this Thesis is the result of original research, the greater part of which was completed subsequent to admission for the degree. Signed: Date: Neville Stuart Drury 2 CONTENTS Introduction 5 Chapter One: Rosaleen Norton – A Biographical Overview 16 Chapter Two: Sources of the Western Esoteric Tradition 61 Chapter Three: Aleister Crowley and the Magic of the Left-Hand Path 127 Chapter Four: Rosaleen Norton’s Magical Universe 214 Chapter Five: Rosaleen Norton’s Magical Practice 248 Chapter Six: Rosaleen Norton as a Magical Artist 310 Chapter Seven: Theories and Definitions of Magic 375 Chapter Eight: Rosaleen Norton’s Contribution to the Western Esoteric Tradition 402 Appendix A: Transcript of the interview between Rosaleen Norton and L.J. -

Journal83-1.Pdf

The Delius Society Journal July 1984',Number 83 The DeliusSociety Full Membershipf,8.00 per year Studentsf,5.00 Subscriptionto Libraries(Journal only) f,6.00 per year USA and CanadaUS $ 17.00 per year President Eric Fenby OBE, Hon D Mus, Hon D Litt, Hon RAM Vice Presidents The Rt Hon Lord Boothby KBE, LLD Felix AprahamianHon RCO Roland GibsonM Sc,Ph D (FounderMember) Sir CharlesGroves CBE Stanford RobinsonOBE, ARCM (Hon), Hon CSM MeredithDavies CBE, MA, B Mus, FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE, Hon D Mus Vernon Handley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse, Mount Park Road,Harrow, Middlesex Treasurer Peter Lyons 160 WishingTree Road, St. Leonards-on-Sea,East Sussex Secretary Miss Diane Eastwood 28 Emscote Street South, Bell Hall, Halifax, Yorkshire Tel: (0422) 50537 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill, Luton,Bedfordshire LUI 5EG Tel: Luton (0582)20075 Contents Editoria! 'Delius as they saw him' by Robert Threlfall Kenneth Spenceby Lionel Hill t9 Margot La Rouge at Camden Festival 2l RPS Sir John Barbirolli concert 23 Midlands Branch meetins: Arnold Bax 24 Cynara in the Midlands 24 Midlands Branch meeting: an eveningof film 25 Forthcoming Events 26 Acknowledgements The cover illustration is an early sketchof Delius by Edvard Munch (no. 1 in Robert Threlfall's Iconography,see page 7), reproducedby kind per- missionof the Curator of the Munch Museum, Oslo. The photographicplates in this issuehave been financed by a legacyto the Delius Societyfrom the late Robert Aickman. The photographson pp. 8, 9 and 17 are reproduced by kind permission of Andrew Boyle with acknowledgementto Lionel Carley, the owner of the two heads.The two photographson page 13were taken by the Editor with the permissionof Denis Blood. -

Toccata Classics TOCC0147 Notes

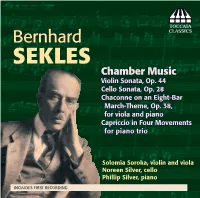

TOCCATA Bernhard CLASSICS SEKLES Chamber Music Violin Sonata, Op. 44 Cello Sonata, Op. 28 Chaconne on an Eight-Bar March-Theme, Op. 38, for viola and piano ℗ Capriccio in Four Movements for piano trio Solomia Soroka, violin and viola Noreen Silver, cello Phillip Silver, piano INCLUDES FIRST RECORDING REDISCOVERING BERNHARD SEKLES by Phillip Silver he present-day obscurity of Bernhard Sekles illustrates how porous is contemporary knowledge of twentieth-century music: during his lifetime Sekles was prominent as teacher, administrator and composer alike. History has accorded him footnote status in two of these areas of endeavour: as an educator with an enviable list of students, and as the Director of the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt from 923 to 933. During that period he established an opera school, much expanded the area of early-childhood music-education and, most notoriously, in 928 established the world’s irst academic class in jazz studies, a decision which unleashed a storm of controversy and protest from nationalist and fascist quarters. But Sekles was also a composer, a very good one whose music is imbued with a considerable dose of the unexpected; it is traditional without being derivative. He had the unenviable position of spending the prime of his life in a nation irst rent by war and then enmeshed in a grotesque and ultimately suicidal battle between the warring political ideologies that paved the way for the Nazi take-over of 933. he banning of his music by the Nazis and its subsequent inability to re-establish itself in the repertoire has obscured the fact that, dating back to at least 99, the integration of jazz elements in his works marks him as one of the irst European composers to use this emerging art-form within a formal classical structure. -

Table of Contents Provided by Blackwell's Book Services and R.R

List of Illustrations p. xiii Chronology p. xv Introduction p. xxi The Man Forebears p. 5 [The Aldridge Saga Begins] (1933) [Aldridge Family Strengths] (1933) [Aldridge Family Weaknesses] (1933) [Frank and Clara Aldridge] (1933) Father p. 15 John H. Grainger (1956) [John H. Grainger in Adelaide] (ca. 1933) My Father's Comment on Cyril Scott's Magnificat (1953) Mother's Experience with Scotch & Irish (1953) How Would We Ordinary Men Get On If the Clever Ones Did Not Destroy Themselves? (1953) My Father in My Childhood (1954) Mother p. 27 Dates of Important Events and Movements in the Life of Rose Grainger (1923) [How I Have Loved Her, How I Love Her Now] (1922) Thought Mother Was 'God'. Something of This Still Remains (1923) Arguments with Beloved Mother (1926) Mother's Neuralgia in Australia (1926) Mother on My Love of Being Pitied (1926) Beloved Mother's Swear-Words (1926) Mother a Nietzschean? (1926) Thots of Mother while Scoring To a Nordic Princess (1928) Bird's-Eye View of the Together-Life of Rose Grainger and Percy Grainger (1947) Friends p. 79 [Dr Henry O'Hara] (1933) Dr Hamilton Russell Called Me 'A Tiger for Work' (1953) A Day of Motoring with Dr Russell (1953) Karl Klimsch's Purse of Money, for Mother to Get Well On (1945) The English Are Fickle Friends, Tho Never Vicious in Their Fickleness (1954) My First Meeting with Cyril Scott (1944) Walter Creighton & Cyril Scott (1944) Walter Creighton on Roger Quilter's Hide-Fain-th ((Secretiveness)) (1944) Roger Quilter Failed Me at Harrogate (1944) Balfour Gardiner Disliked What He Considered Political Falsification in Busoni & Harold Bauer (1953) Balfour Gardiner with Me in Norway, 1922 (1953) Mrs L[owrey] and My Early London Days (1945) Frau Kwast-Hiller, Evchen, Mrs Lowrey in Berlin (1953) Miss Devlin's Sweet Australian Ways (1953) Jacques Jacobs on First Ada Crossley Tour (1953) Eliza Wedgewood, Out to Buy Old Furniture from Folksingers (1953) Sargent's and His Set's Set-of-Mind toward My Betrothal to Margot (1944) Wife p. -

IGOR STRAVINSKY (1882-1971) IGOR STRAVINSKY SOMMCD 266-2 Music for Solo Piano (CD1) Music for Piano and Orchestra (CD2)* Music For

IGOR STRAVINSKY (1882-1971) IGOR STRAVINSKY SOMMCD 266-2 Music for Solo Piano (CD1) Music for Piano and Orchestra (CD2)* Music for Southampton Piano Solo and Piano and Orchestra TURNER SIMS Peter Donohoe piano Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra * David Atherton conductor * CD1 1 - 3 Three Movements from Petrushka 16:50 4 - 7 Four Etudes, Op. 7 8:19 2000 © 2000. Venue & Personnel as above. & Personnel Venue 2000 © 2000. 8 - bm Piano Sonata in F-sharp minor 29:15 bn - bp Piano Sonata (1924) 10:18 Total duration: 64:43 CD2 1 - 4 Serenade in A 11:43 5 Piano-Rag-Music 3:34 6 Tango 3:13 7 - 9 Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments* 19:18 bl - bp Movements for Piano and Orchestra* 9:30 : Recorded in Tsuen Wan Town Hall, Hong Kong, 4-6 July 1995. Hong Kong, Hall, Town Wan Tsuen in : Recorded bq - bs Capriccio for Piano and Orchestra* 16:35 PETER DONOHOE piano 2000 HK Phil under exclusive licence to GMN Inc to © 2000 GMN licence under exclusive 2000 HK Phil Total duration: 64:04 CD 1 and tracks 1 to 6 of CD 2 recorded 14-16 6 of CD 2 recorded 1 to CD 1 and tracks September 2016 and 24 June 2017 Arden-Taylor. Engineer: Paul Oke. Siva Southampton. Producer: Sims Concert Hall, Turner at Capriccio Earth. Engineer: Mike Floating Johns. Hatch, Stephen Producer: Jan 26-29, 1999. Concerto & Movements: Piano Front cover photo: © 2017 Olivier Fleury / Festival International de Musique de Dinard International de Musique de Dinard © 2017 Olivier Fleury photo: / Festival cover Front Design: Andrew Giles Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra © & 2018 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND DDD Made in the EU DAVID ATHERTON IGOR STRAVINSKY CD 1 IGOR STRAVINSKY CD 2 Three Movements from Petrushka (16:50) Serenade in A (11:43) 1 1. -

Otto Klemperer Curriculum Vitae

Dick Bruggeman Werner Unger Otto Klemperer Curriculum vitae 1885 Born 14 May in Breslau, Germany (since 1945: Wrocław, Poland). 1889 The family moves to Hamburg, where the 9-year old Otto for the first time of his life spots Gustav Mahler (then Kapellmeister at the Municipal Theatre) out on the street. 1901 Piano studies and theory lessons at the Hoch Conservatory, Frankfurt am Main. 1902 Enters the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory in Berlin. 1905 Continues piano studies at Berlin’s Stern Conservatory, besides theory also takes up conducting and composition lessons (with Hans Pfitzner). Conducts the off-stage orchestra for Mahler’s Second Symphony under Oskar Fried, meeting the composer personally for the first time during the rehearsals. 1906 Debuts as opera conductor in Max Reinhardt’s production of Offenbach’s Orpheus in der Unterwelt, substituting for Oskar Fried after the first night. Klemperer visits Mahler in Vienna armed with his piano arrangement of his Second Symphony and plays him the Scherzo (by heart). Mahler gives him a written recommendation as ‘an outstanding musician, predestined for a conductor’s career’. 1907-1910 First engagement as assistant conductor and chorus master at the Deutsches Landestheater in Prague. Debuts with Weber’s Der Freischütz. Attends the rehearsals and first performance (19 September 1908) of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony. 1910 Decides to leave the Jewish congregation (January). Attends Mahler’s rehearsals for the first performance (12 September) of his Eighth Symphony in Munich. 1910-1912 Serves as Kapellmeister (i.e., assistant conductor, together with Gustav Brecher) at Hamburg’s Stadttheater (Municipal Opera). Debuts with Wagner’s Lohengrin and conducts guest performances by Enrico Caruso (Bizet’s Carmen and Verdi’s Rigoletto). -

Lincolnshire Posy Abbig

A Historical and Analytical Research on the Development of Percy Grainger’s Wind Ensemble Masterpiece: Lincolnshire Posy Abbigail Ramsey Stephen F. Austin State University, Department of Music Graduate Research Conference 2021 Dr. David Campo, Advisor April 13, 2021 Ramsey 1 Introduction Percy Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy has become a staple of wind ensemble repertoire and is a work most professional wind ensembles have performed. Lincolnshire Posy was composed in 1937, during a time when the wind band repertoire was not as developed as other performance media. During his travels to Lincolnshire, England during the early 20th century, Grainger became intrigued by the musical culture and was inspired to musically portray the unique qualities of the locals that shared their narrative ballads through song. While Grainger’s collection efforts occurred in the early 1900s, Lincolnshire Posy did not come to fruition until it was commissioned by the American Bandmasters Association for their 1937 convention. Grainger’s later relationship with Frederick Fennell and Fennell’s subsequent creation of the Eastman Wind Ensemble in 1952 led to the increased popularity of Lincolnshire Posy. The unique instrumentation and unprecedented performance ability of the group allowed a larger audience access to this masterwork. Fennell and his ensemble’s new approach to wind band performance allowed complex literature like Lincolnshire Posy to be properly performed and contributed to establishing wind band as a respected performance medium within the greater musical community. Percy Grainger: Biography Percy Aldridge Grainger was an Australian-born composer, pianist, ethnomusicologist, and concert band saxophone virtuoso born on July 8, 1882 in Brighton, Victoria, Australia and died February 20, 1961 in White Plains, New York.1 Grainger was the only child of John Harry Grainger, a successful traveling architect, and Rose Annie Grainger, a self-taught pianist. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father.