The Delius Society Journal Spring 2013, Number 153

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITEL PROUDLY REPRESENTS the INTERNATIONAL TV DISTRIBUTION of Browse Through the Complete Unitel Catalogue of More Than 2,000 Titles At

UNITEL PROUDLY REPRESENTS THE INTERNATIONAL TV DISTRIBUTION OF Browse through the complete Unitel catalogue of more than 2,000 titles at www.unitel.de Date: March 2018 FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] [email protected] Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] CONTENT BRITTEN: GLORIANA Susan Bullock/Toby Spence/Kate Royal/Peter Coleman-Wright Conducted by: Paul Daniel OPERAS 3 Staged by: Richard Jones BALLETS 8 Cat. No. A02050015 | Length: 164' | Year: 2016 DONIZETTI: LA FILLE DU RÉGIMENT Natalie Dessay/Juan Diego Flórez/Felicity Palmer Conducted by: Bruno Campanella Staged by: Laurent Pelly Cat. No. A02050065 | Length: 131' | Year: 2016 OPERAS BELLINI: NORMA Sonya Yoncheva/Joseph Calleja/Sonia Ganassi/ Brindley Sherratt/La Fura dels Baus Conducted by: Antonio Pappano Staged by: Àlex Ollé Cat. -

COCKEREL Education Guide DRAFT

VICTOR DeRENZI, Artistic Director RICHARD RUSSELL, Executive Director Exploration in Opera Teacher Resource Guide The Golden Cockerel By Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov Table of Contents The Opera The Cast ...................................................................................................... 2 The Story ...................................................................................................... 3-4 The Composer ............................................................................................. 5-6 Listening and Viewing .................................................................................. 7 Behind the Scenes Timeline ....................................................................................................... 8-9 The Russian Five .......................................................................................... 10 Satire and Irony ........................................................................................... 11 The Inspiration .............................................................................................. 12-13 Costume Design ........................................................................................... 14 Scenic Design ............................................................................................... 15 Q&A with the Queen of Shemakha ............................................................. 16-17 In The News In The News, 1924 ........................................................................................ 18-19 -

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

Syphilis' Impact on Late Works of Classical Music Composers

SYPHILIS’ IMPACT ON LATE WORKS OF CLASSICAL MUSIC COMPOSERS Rempelakos L1, Poulakou-Rebelakou E1, Tsiamis C1, Rempelakos A2 1History of Medicine, Athens University Medical School, Athens, Greece 2Urologic Department, Hippocrateion Hospital, Athens, Greece INTRODUCTION & OBJECTIVE: To present the effects of the tertiary stage syphilis on the last works of some famous European classical music composers who suffered from the disease. METHODS: The review of the biographies of seven documented syphilis cases of composers, focusing on the events of their last period of life and the review of the critics for their artistic expression under disease-affected circumstances. RESULTS: The 19th century is undeniably considered as the golden age of classical music but, at the same time, some of the most famous composers were victims of this disease-menace, strongly stigmatizing themselves and their families, the latter trying to keep the shameful secret, aftermath destructing sources and documents. Seven cases of musicians with syphilis have been studied: Franz Schubert died at the age of 31, while Robert Schumann and Hugo Wolf (age at death 46 and 43 respectively), both attempted suicide and passed the rest of their lives in insane asylums. Moreover, Gaetano Donizetti infected his wife, Virginia, who died in childbirth before his own death occurring between catatonic symptoms and bouts of persecution mania. Bedrich Smetana predicted his death entitling his composition “final page” and indeed, he did not compose anymore and died soon in a mental asylum. Frederick Delius lived for fifteen years blind and paralyzed dictating his scores to a young follower of his music, although the quality of the late compositions cannot be compared with the priors. -

Neil Thomson — Biografia

Neil Thomson — Biografia Neil Thomson é um dos mais respeitados e versáteis maestros britânicos de sua geração. Nascido em 1966, estudou com Norman Del Mar na Royal College of Music em Londres e mais tarde em Tanglewood, com Leonard Bernstein e Kurt Sanderling. O maestro assume em 2014 a regência titular e direção artística da Orquestra Filarmônica de Goiás. Ele já gravou com a Orquestra Sinfônica de Londres, Orquestra Filarmônica Real de Liverpool e trabalhou nos concertos da Orquestra Filarmônica de Londres, da Philharmonia, da Orquestra Filarmônica da BBC, da Royal Scottish National Orchestra, da Hallé, da Orquestra Filarmônica Real, da Aarhus Symphony Orchestra, da Orquestra do Teatro Massimo em Palermo, Orquestra Sinfônica de Yucatan no México, Romanian Radio Chamber Orchestra e a RTE Concert Orchestra. Em maio de 2005, o maestro foi convidado para reger o concerto em homenagem ao cinquentenário da morte de George Enescu com a Orquestra Nacional da Romênia e os solistas David Geringas e Carmen Oprisanu. Ele fez atualmente estreias bem-sucedidas com a Orquestra Filarmônica de Tóquio, com as Orquestras Sinfônicas de Lahtu e de Oulu na Finlândia, a Royal Northern Sinfonia, a Orquestra Sinfônica de Israel, a Orquestra Sinfonica do Porto Casa da Música, a Orquestra da Rádio WDR, a Koln, Orquestra da Ópera Nacional de Gales, Orchestra of Opera North, a Royal Oman Symphony Orchestra, a Aurora Orchestra e a Nordic Youth Orchestra. Ele tem se apresentado com vários solistas ilustres, como Sir James Galway, Dame Moura Lympany, Sir Thomas Allen, Dame Felicity Lott, Philip Langridge, Sarah Chang, Ittai Shapira, Steven Isserlis, Julian Lloyd Webber, David Geringas, Natalie Clein, Gyorgy Pauk, Brett Dean, Jean-Philippe Collard,Stephen Hough,Peter Jablonski e Sir Richard Rodney Bennett. -

Press Information Eno 2013/14 Season

PRESS INFORMATION ENO 2013/14 SEASON 1 #ENGLISHENO1314 NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 CONTENTS Autumn 2013 4 FIDELIO Beethoven 6 DIE FLEDERMAUS Strauss 8 MADAM BUtteRFLY Puccini 10 THE MAGIC FLUte Mozart 12 SATYAGRAHA Glass Spring 2014 14 PeteR GRIMES Britten 18 RIGOLetto Verdi 20 RoDELINDA Handel 22 POWDER HeR FAce Adès Summer 2014 24 THEBANS Anderson 26 COSI FAN TUtte Mozart 28 BenvenUTO CELLINI Berlioz 30 THE PEARL FISHERS Bizet 32 RIveR OF FUNDAMent Barney & Bepler ENGLISH NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 3 FIDELIO NEW PRODUCTION BEETHoven (1770–1827) Opens: 25 September 2013 (7 performances) One of the most sought-after opera and theatre directors of his generation, Calixto Bieito returns to ENO to direct a new production of Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio. Bieito’s continued association with the company shows ENO’s commitment to highly theatrical and new interpretations of core repertoire. Following the success of his Carmen at ENO in 2012, described by The Guardian as ‘a cogent, gripping piece of work’, Bieito’s production of Fidelio comes to the London Coliseum after its 2010 premiere in Munich. Working with designer Rebecca Ringst, Bieito presents a vast Escher-like labyrinth set, symbolising the powerfully claustrophobic nature of the opera. Edward Gardner, ENO’s highly acclaimed Music Director, 2013 Olivier Award-nominee and recipient of an OBE for services to music, conducts an outstanding cast led by Stuart Skelton singing Florestan and Emma Bell as Leonore. Since his definitive performance of Peter Grimes at ENO, Skelton is now recognised as one of the finest heldentenors of his generation, appearing at the world’s major opera houses, including the Metropolitan Opera, New York, and Opéra National de Paris. -

CHAN 3000 FRONT.Qxd

CHAN 3000 FRONT.qxd 22/8/07 1:07 pm Page 1 CHAN 3000(2) CHANDOS O PERA IN ENGLISH David Parry PETE MOOES FOUNDATION Puccini TOSCA CHAN 3000(2) BOOK.qxd 22/8/07 1:14 pm Page 2 Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) Tosca AKG An opera in three acts Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica after the play La Tosca by Victorien Sardou English version by Edmund Tracey Floria Tosca, celebrated opera singer ..............................................................Jane Eaglen soprano Mario Cavaradossi, painter ..........................................................................Dennis O’Neill tenor Baron Scarpia, Chief of Police................................................................Gregory Yurisich baritone Cesare Angelotti, resistance fighter ........................................................................Peter Rose bass Sacristan ....................................................................................................Andrew Shore baritone Spoletta, police agent ........................................................................................John Daszak tenor Sciarrone, Baron Scarpia’s orderly ..............................................Christopher Booth-Jones baritone Jailor ........................................................................................................Ashley Holland baritone A Shepherd Boy ............................................................................................Charbel Michael alto Geoffrey Mitchell Choir The Peter Kay Children’s Choir Giacomo Puccini, c. 1900 -

Disability and Music

th nd 19 November to 22 December UKDHM 2018 will focus on Disability and Music. We want to explore the links between the experience of disablement in a world where the barriers faced by people with impairments can be overwhelming. Yet the creative impulse, urge for self expression and the need to connect to our fellow human beings often ‘trumps’ the oppression we as disabled people have faced, do face and will face in the future. Each culture and sub-culture creates identity and defines itself by its music. ‘Music is the language of the soul. To express ourselves we have to be vibrating, radiating human beings!’ Alasdair Fraser. Born in Salford in 1952, polio survivor Alan Holdsworth goes by the stage name ‘Johnny Crescendo’. His music addresses civil rights, disability pride and social injustices, making him a crucial voice of the movement and one of the best-loved performers on the disability arts circuit. In 1990 and 1992, Alan co- organised Block Telethon, a high-profile media and community campaign which culminated in the demise of the televised fundraiser. His albums included Easy Money, Pride and Not Dead Yet, all of which celebrate disabled identity and critique disabling barriers and attitudes. He is best known for his song Choices and Rights, which became the anthem for the disabled people’s movement in Britain in the late 1980s and includes the powerful lyrics: Choices and Right That’s what we gotta fight for Choices and rights in our lives I don’t want your benefit I want dignity from where I sit I want choices and rights in our lives I don’t want you to speak for me I got my own autonomy I want choices and rights in our lives https://youtu.be/yU8344cQy5g?t=14 The polio virus attacked the nerves. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op

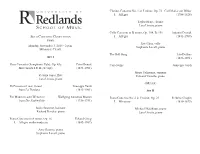

Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F minor, Op. 73 Carl Maria von Weber I. Allegro (1786-1826) Taylor Heap, clarinet Lara Urrutia, piano Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104, B. 191 Antonin Dvorák SOLO CONCERTO COMPETITION I. Allegro (1841-1904) Finals Xue Chen, cello Monday, November 3, 2014 - 2 p.m. Stephanie Lovell, piano MEMORIAL CHAPEL The Bell Song Léo Delibes SET I (1836-1891) Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op. 43a Peter Benoit Caro Nome Guiseppe Verdi Movements I & II (excerpt) (1834-1901) Mayu Uchiyama, soprano Victoria Jones, flute Edward Yarnelle, piano Lara Urrutia, piano - BREAK - Di Provenza il mar, il suol Giuseppe Verdi from La Traviata (1813-1901) SET II Ein Madehen oder Weibchen Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 Frédéric Chopin from Die Zauberflöte (1756-1791) I. Maestoso (1810-1849) Justin Brunette, baritone Michael Malakouti, piano Richard Bentley, piano Lara Urrutia, piano Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 Edvard Grieg I. Allegro molto moderato (1843-1907) Amy Rooney, piano Stephanie Lovell, piano Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle Charles Gounod ABOUT THE CONCERTO COMPETITION from Roméo et Juliette (1818-1893) Beginning in 1976, the Concerto Competition has become an annual event Cruda Sorte Gioacchino Rossini for the University of Redlands School of Music and its students. Music from L’Ataliana in Algeri (1792-1868) students compete for the coveted prize of performing as soloist with the Redlands Symphony Orchestra, the University Orchestra or the Wind Jordan Otis, soprano Ensemble. Twyla Meyer, piano This year the Preliminary Rounds of the Competition took place on Friday, October 31st and Saturday, November 1st. -

Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’

‘The Art-Twins of Our Timestretch’: Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’ Catherine Sarah Kirby Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Music (Musicology) April 2015 Melbourne Conservatorium of Music The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract This thesis explores Percy Grainger’s promotion of the music of Frederick Delius in the United States of America between his arrival in New York in 1914 and Delius’s death in 1934. Grainger’s ‘Delius campaign’—the title he gave to his work on behalf of Delius— involved lectures, articles, interviews and performances as both a pianist and conductor. Through this, Grainger was responsible for a number of noteworthy American Delius premieres. He also helped to disseminate Delius’s music by his work as a teacher, and through contact with publishers, conductors and the press. In this thesis I will examine this campaign and the critical reception of its resulting performances, and question the extent to which Grainger’s tireless promotion affected the reception of Delius’s music in the USA. To give context to this campaign, Chapter One outlines the relationship, both personal and compositional, between Delius and Grainger. This is done through analysis of their correspondence, as well as much of Grainger’s broader and autobiographical writings. This chapter also considers the relationship between Grainger, Delius and others musicians within their circle, and explores the extent of their influence upon each other. Chapter Two examines in detail the many elements that made up the ‘Delius campaign’. -

Download the Concert Programme (PDF)

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Wednesday 15 February 2017 7.30pm Barbican Hall UK PREMIERE: MARK-ANTHONY TURNAGE London’s Symphony Orchestra Mark-Anthony Turnage Håkan (UK premiere, LSO co-commission) INTERVAL Rachmaninov Symphony No 2 John Wilson conductor Håkan Hardenberger trumpet Concert finishes approx 9.30pm Supported by LSO Patrons 2 Welcome 15 February 2017 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief Welcome to tonight’s LSO concert at the Barbican, THE LSO ON TOUR which features the UK premiere of one of two works by Mark-Anthony Turnage co-commissioned by the This month, the LSO will embark on a landmark LSO this season. Håkan is Mark-Anthony Turnage’s tour of the Far East. On 20 February the Orchestra second work for trumpeter Håkan Hardenberger; will open the UK-Korea Year of Culture in Seoul, regular members of the audience will remember the followed by performances in Beijing, Shanghai and LSO’s performance of the first concerto, From the Macau. To conclude the tour, on 4 March the LSO will Wreckage, in 2013. It is a great pleasure to welcome make history by becoming the first British orchestra this collaboration of composer and soloist once again. to perform in Vietnam, conducted by Elim Chan, winner of the 2014 Donatella Flick LSO Conducting The LSO is very pleased to welcome conductor Competition. A trip of this scale is possible thanks to John Wilson for this evening’s performance, and the support of our tour partners. The LSO is grateful is grateful to him for stepping in to conduct at to Principal Partner Reignwood, China Taiping, short notice.