The Ubuntu Strategy”: Commodification and the Affective Politics of Ubuntu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogo Delle Attività 25-09-2021 11.42.29

Catalogo delle attività 25-09-2021 11.42.29 Class. Nome Telefono Indirizzo Web / Email 0 0.0 Agrisostenibile 20 % SCEC 3898450518 Lavori agricoli di ogni genere. Via Trieste 23 80030 Visciano - Napoli [email protected] Allgreendone 30 % SCEC 3203312475 Termoidraulica, assistenza cellulari,animatore,cameriere, agricoltore, lezioni d'inglese, spagnolo e catalano. Via Verdi 13 80030 Visciano - Napoli [email protected] Associazione Manes 10 % SCEC 3409426212 L'Associazione Manes è nata nella primavera del 2009 attraverso l'incontro di persone che hanno riconosciuto l'importanza dell'educazione nell'organismo sociale. I fondatori hanno deciso di mettere a disposizione e condividere le proprie risorse culturali. Nell'Associazione Manes confluiscono anche quelle persone che sentono di avere dei bisogni nella sfera educativa, artistica e di autoeducazione. L'associazione associa all'attività di ricerca anche quella di divulgazione attraverso convegni, conferenze, corsi e consulenze. L'etimologia della parola educare è come ormai noto quella di tirare fuori e noi dell'Associazione Manes abbiamo cominciato da noi stessi a tirar fuori i nostri talenti e percorsi di ricerca e non ci stancheremo mai di condividere, arricchire e confrontarci con i percorsi altrui. Siamo certi che la competizione appartenga alla sfera culturale perché siamo tutti chiamati alla studio e confronto dell'intuizione pedagogica, del metodo, dell'idea migliore. La ricerca giammai si può considerare conclusa, è un percorso che non ha traguardi ma sempre solo nuove mete. Ci ispiriamo al lavoro di Rudolf Steiner e dei continuatori della sua opera, consapevoli che il genio si manifesta in molteplici forme abbiamo incluso e includeremo tutti quei percorsi che abbiamo riconosciuto e riconosceremo validi attraverso la sperimentazione diretta. -

20P Be Levied on Each Polystyrene Box Taken from the Refectory

Union General Meeting Motion Title: 20p be levied on each polystyrene box taken from the Refectory Proposer: Edmund Bower Seconder: Guido Manfrini This Union Notes: 1.1 That the Refectory does not currently charge for polystyrene boxes 1.2 That the shop does charge 10p for paper cups which biodegrade. 1.3 That polystyrene boxes do not biodegrade and are more harmful to the environment than paper cups 1.4 That the boxes are often used needlessly instead of plates for consumption within the canteen itself This Union Believes: 2.1 A small charge on these boxes would drastically cut down on their use 2.2 That it is not unreasonable to expect those who want to use a box to pay a charge 2.3 That those who need who genuinely need to use the boxes would be prepared to pay a small fee for them This Union Resolves: 3.1 A small charge of 20p be levied on each polystyrene box taken from the Refectory 3.2 Lobby Elior to encourage them to provide biodegradable boxes, or else make food 20p cheaper. Union General Meeting Motion Title: A better practise space for SOAS samba band Proposer: Ella Jeffreys Seconder: Maren Johansen This Union Notes: 1.1 That Samba is an integral part of of the SOAS student lifestyle. 1.2 That Samba have to practice at Russell Square. 1.3 That Samba practice can be distracting for those who have to study on Tuesday evenings. This Union Believes: 2.1 That Samba needs a consistent, secure and preferably soundproofed place to practice to keep the band healthy. -

Product Name Flavour Energy (Kj) Per 100Ml Energy (Kcals) Per 100Ml Energy (Kcals) Per 330Ml* Serving Sugars (G) Per 100Ml Sugar

Energy (kcals) Energy (kJ) Energy (kcals) Sugars (g) per 330ml* Product Name Flavour per 330ml* Sugars (g) per 100ml per 100ml per 100ml serving serving Fentimans Traditional Curiosity Cola 750ml Cola 196 47 154 11.3 37 Lidl Freeway Cola Cola 190 45 150 10.9 36 Tesco Classic Cola 2 Litre Cola 184 44 145 10.9 36 Sainsbury's Classic Cola 2L Cola 184 44 145 10.8 36 Marks & Spencer Cola Cola 185 44 146 10.7 35 Essential Waitrose Cola 2 litres Cola 184 44 145 10.7 35 Asda Chosen by You Cola 2 Litres Cola 183 44 144 10.7 35 Coca-Cola 2 Litre Cola 180 43 142 10.6 35 Morrisons Cola Cola 186 44 147 10.6 35 Pepsi can Cola 182 43 143 10.6 35 Aldi VIVE Original Cola Cola 181 43 143 10.6 35 Barr Cola 500ml Cola 180 43 142 10.4 34 The Co-operative Cola 2 Litre Cola 180 43 142 10.4 34 UBUNTU cola Cola 176 42 139 10.4 34 Dr Pepper 2 Litre Cola 177 42 140 10.4 34 Tesco Original Cola Cola 165 39 130 9.7 32 Barr's Originals Cream Soda with a Twist of Raspberry 330ml Cream Soda 195 47 154 11.5 38 Marks & Spencer Cream Soda Cream Soda 185 44 146 10.9 36 Waitrose Cream Soda 2 Litres Cream Soda 181 43 143 10.6 35 Asda Chosen by You Cream Soda 2 Litres Cream Soda 107 26 84 6.1 20 Fentimans Traditional Dandelion & Burdock 750ml Dandelion & Burdock 196 47 154 11.8 39 Marks & Spencer Dandelion & Burdock Dandelion & Burdock 165 39 130 9.8 32 Asda Chosen by You Dandelion & Burdock 2 Litres Dandelion & Burdock 125 30 99 6.8 22 Morrisons Dandelion & Burdock Dandelion & Burdock 87 21 69 4.2 14 Tesco Finest Grape & Elderflower Spritz Elderflower 192 46 151 11.3 37 Shloer -

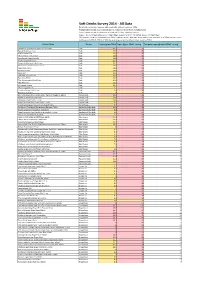

Soft Drinks Survey 2014

Soft Drinks Survey 2014 - All Data Data table sorted by category, alphabetically, highest sugar per 100g Product information was collected online, instore or direct from manufacturers Colour coding based on new front of pack traffic Light labelling criteria Sugars - Red >13.5g/portion or >11.25g/100g, Amber >2.5≤11.25/100g, Green ≤2.25g/100g *serving size has been standardised to 330ml, regular can size. Product Name Flavour Sugars/100g Sugars/330ml* serving Teaspoons sugar equiv/330ml* serving Fentimans Traditional Curiosity Cola 750ml Cola 11.3 37 9 Best-in American Cola Cola 10.9 36 9 Lidl Freeway Cola Cola 10.9 36 9 Tesco Classic Cola 2 Litre Cola 10.9 36 9 Sainsbury's Classic Cola 2L Cola 10.8 36 9 Marks & Spencer Cola Cola 10.7 35 9 Essential Waitrose Cola 2 litres Cola 10.7 35 9 Asda Chosen by You Cola 2 Litres Cola 10.7 35 9 Coca-Cola 2 Litre Cola 10.6 35 9 Morrisons Cola Cola 10.6 35 9 Pepsi can Cola 10.6 35 9 Aldi VIVE Original Cola Cola 10.6 35 9 Barr Cola 500ml Cola 10.4 34 9 The Co-operative Cola 2 Litre Cola 10.4 34 9 UBUNTU cola Cola 10.4 34 9 Dr Pepper 2 Litre Cola 10.4 34 9 Tesco Original Cola can Cola 10.2 34 8 Tesco Original Cola Cola 9.7 32 8 Country Spring Cola 3 Litre Cola 4.8 16 4 Best-in Cola 2 Litre Cola 4 13 3 Barr's Originals Cream Soda with a Twist of Raspberry 330ml Cream Soda 11.5 38 9 Marks & Spencer Cream Soda Cream Soda 10.9 36 9 Waitrose Cream Soda 2 Litres Cream Soda 10.6 35 9 Asda Chosen by You Cream Soda 2 Litres Cream Soda 6.1 20 5 Country Spring American Cream Soda 3 Litres Cream Soda 5.7 19 5 Fentimans -

A Fair Chance to Know It's Fair

A Fair Chance to Know It’s Fair A study of online communication within the field of Fair Trade consumption Sara Blomberg Maria Busck Student Umeå School of Business and Economics Degree Project, 30 ECTS Spring semester 2013 Supervisor: Vladimir Vanyushyn II ABSTRACT The rise of ethical consumerism has contributed to that organisations increasingly include CSR policies in their business and marketing strategies. Consumers want to make more ethically based purchasing decisions, and are guided by organisations’ ethical claims and by product labels. However, there are many different ethical organisations and labels on the market today and consumers find it difficult to separate them and know what each of them stands for. Ethical consumerism stems from green consumerism and has contributed to the development and rise of the Fair Trade movement. The general idea of Fair Trade is to support producers in poor countries, and by purchasing Fair Trade products consumers can contribute to realising the Fair Trade objectives. Previous research has identified a gap between consumers’ attitudes and actual behaviour regarding Fair Trade consumption. Consumers clearly express a positive attitude towards the Fair Trade movement and Fair Trade products, but their attitudes are not reflected in actual purchases. Researchers suggest that the gap could depend on lack of information and proof that Fair Trade actually contribute to better working and living conditions of producers in poor countries, but this had not yet been investigated. Our main purpose with this degree project is to identify factors that could affect the attitude-behaviour gap, and more precisely how access to information affects the existing gap. -

A Thirst for Sugar? New Research Exposes Shockingly High Sugar Content in Fizzy Drinks and Calls for Immediate Action

Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine Barts and The London School of Medicine & Dentistry Queen Mary University of London Telephone: 020 7882 6018 London EC1M 6BQ Embargoed until 00.01 hrs GMT 12th June 2014 A THIRST FOR SUGAR? NEW RESEARCH EXPOSES SHOCKINGLY HIGH SUGAR CONTENT IN FIZZY DRINKS AND CALLS FOR IMMEDIATE ACTION 79% of sugary fizzy drinks contain 6 or more teaspoons of sugar per can (330ml) – WHO’s recommended daily MAXIMUM for sugar [1-2] 9 out of 10 sugary fizzy drinks would receive a RED (high) traffic light for sugars [3] A typical can of cola contains as much sugar as three and half Krispy Kreme Donuts [4] Some elderflower sparkling drinks contain more sugars than Coca Cola Two thirds (63%) of ginger beer drinks contain MORE sugars than Coca Cola NEW independent research by Action on Sugar reveals the shockingly high and unnecessary levels of sugar in carbonated sugar-sweetened soft drinks and calls for immediate action NOW to set targets to reduce sugar levels of ALL products in order to halt the obesity epidemic [5]. The survey analysed 232 sugar-sweetened drinks from leading supermarkets [6]. Interestingly the findings revealed huge variations in the sugar content of very similar products, demonstrating sugar levels can come down significantly in soft drinks without it drastically affecting the taste [7]. Sugar-sweetened fizzy drinks are a large contributor to sugars in our diets, especially for children and a hidden source of calories. On average, 16% of adult’s daily added sugar intake comes from soft drinks. For teenagers, it makes up nearly a THIRD (29%) of their daily added sugar intake and contributes to 4.8% of their total energy intake [8]. -

MAY JUNE 2019 VEGAN a Bit More About It

VEGAN MAY JUNE 2019 VEGAN A bit more about it.. People choose to be vegan for health, environmental, and/or ethical reasons. Some vegans feel that consuming eggs and dairy products promotes the meat industry. Some people avoid these items because of the conditions associated with their production. Many vegans choose this lifestyle to promote a more humane and caring world. They know they are not perfect, but believe they have a responsibility to try to do their best, while not being judgmental of others. Whatever your reason for choosing vegan, we have everything that you could wish for, this list includes cheese, milk and meat alternatives, vegan chocolate and much more. Key BFGSOV B - Biodynamic // F - Fairtrade // G - Gluten-Free // 0 - Organic // S - Added Sugar // V - Vegan All prices are correct at time of print and stock is subject to availabilty. code product size rrp bfgosv ALCOHOL FREE BEVERAGES BOTONIQUE JU789 Blush 750ml 7.99 V JU791 Crisp White 750ml 7.99 V ALCOHOLIC DRINKS FENTIMANS & BLOOM RT031 Gin & Rose Lemonade 275ml 4.15 SV RT005 Gin and Tonic 275ml 4.15 SV HOLLOWS From Fentimans RT013 Superior Alcoholic Ginger Beer 330ml 2.25 SV RT017 Superior Alcoholic Ginger Beer 500ml 5.35 SV BABY & CHILD FOOD ANNABEL KARMEL BB092 Baby Pasta Shells 250g 1.39 OV BABEASE BB100 Banana & Pear Coconut Water 100g 1.35 GOV BB088 Butternut, Carrot & Broccli 100g 1.35 GOV BB090 Garden Vegetable Risotto 130g 1.75 GOV BB096 Pumpkin & Peas 100g 1.35 GOV BB103 Root Vegetable & Quinoa Pilaf 130g 1.75 GOV BB097 Strawberry,Apple Coconut Water -

Den Finländska Rejäl Handelns Rötter Finns I Ekenäs 2 2/2012 PÄÄKIRJOITUS PS

Reilun kaupan erikoislehti jo vuodesta 1984. Numero 2/2012 Colaa humaanisti Makeaa monessa muodossa Orjuuttava sokeriruoko Den finländska rejäl handelns rötter finns i ekenäs 2 2/2012 PääkirJOitUs Ps. Tammisaaren Emmaus ANNA PALAUTETTA! Mikä miellytti, mikä ärsytti, mikä puhutti tai mikä herätti lisää kysymyksiä tässä lehdessä? – edelläkävijä Arvomme kaikkien 10.10.2012 mennes sä lehteä kommentoineiden kesken 50 euron lahjakortin Maailmankauppojen dag är detta taan kuinka Emmaus toi reilun tyksen henkilöjäsenyhdistys” myös ihmisten asenteisiin, tekee verkkokauppoihin. Lähetä vastauksesi osoitteeseen [email protected] viktigt: vi kaupan ajatuksen ja toiminnan kuten RKEYn silloinen toimin- niistä ”glokaalimpia”. Isojen tai jätä ne Maailmankauppa Kirahvin behöver rötter, Suomeen jo 60-luvulla. Kun nanjohtaja Lasse Kosonen sitä ketjujen myymälöitä parempi markkinatelttaan Tammisaaren (20.– kuvasi, maailmankaupat monilla ostopaikka niin reilun kaupan 21.9.) tai Salon (27.–29.9.) markkinoilla. vi måste ha maan ensimmäinen varsinainen Lehti pidättää oikeuden julkaista vingar. Känslan för lokalsamfun- kehitysmaakauppa, Juuttiputiikki, paikkakunnilla muodostivat sen tuotteille kuin muutenkin, ovat saamiaan kysymyksiä, kommentteja ja ”I palautteita seuraavassa lehdessä sekä det, hembygden måste nödvän- perustettiin Ouluun vuonna 1978, perustaa ja antoivat tilojaan ja pienet lähiruoka- ja luomukaupat verkkosivuillaan. Voit jättää mielipiteesi digt berikas med globalt tänkan- taustavoimana oli Tammisaaren verkostojaan uuden yhdistyksen sekä -

Techniques Et Enjeux Du Recruteur

Techniques et enjeux du recruteur VOS ATTENTES « LA NORMALITÉ N’EST PAS LE SUMMUM DE CE QUE L’ON PEUT ATTEINDRE » « LA PLUPART DES GENS QUI NE TROUVENT PAS LE TRAVAIL DE LEURS RÊVES ÉCHOUENT DANS LEUR QUÊTE NON PAS PARCE QU’ILS MANQUENT D’INFORMATION SUR LE MARCHÉ DE L’EMPLOI, MAIS PARCE QU’ILS MANQUENT D’INFORMATION SUR EUX-MÊMES. » « LA MEILLEURE MANIÈRE DE CONNAÎTRE LA VRAIE SATISFACTION, C’EST DE FAIRE CE QUE VOUS CONSIDÉREZ COMME ÉTANT DU BON TRAVAIL. ET LA MEILLEURE MANIÈRE DE FAIRE DU BON TRAVAIL, C’EST DE FAIRE CE QUE VOUS AIMEZ. SI VOUS N’AVEZ PAS ENCORE TROUVÉ CE QUE VOUS AIMEZ, CONTINUEZ DE CHERCHER » « SI VOTRE QUESTION FINANCIÈRE ÉTAIT RÉSOLUE, COMMENT OCCUPERIEZ-VOUS VOTRE TEMPS ? » HÉRITAGE DE L’ONCLE RALPH ANNÉE 1 : APPRENDRE ANNÉE 2 : S’INVESTIR DANS UNE CAUSE ANNÉE 3 : CARTE BLANCHE RECRUTEMENT 3.0 ? RIEN NE CHANGE L’HISTOIRE DES TAXIS LE SERVICE CLIENT RÉÉQUILIBRAGE DU RAPPORT LA PUISSANCE DES VOIX L’EXPLOSION DE L’EXIGENCE LE CANDIDAT, UN CLIENT ? UNE APPROCHE BUSINESS SOMMES-NOUS LA SNCF ? 81% 85% 79% QUEL EST MON STANDARD ? CE QUI NE FONCTIONNE PAS NE PAS RÉPONDRE AVANCER CACHÉ LE TRAITEMENT INFORME LA LANGUE DE BOIS LA PAROLE DESCENDANTE L’information abonde et circule Équilibrage de la relation candidat- recruteur Risque ou opportunité ? Les ambassadeurs de l’entreprise Marque employeur vs Sourcing La marque employeur 47 82% 75% MAIS AU FAIT ? COMMENT FONCTIONNE … Humanisation de la relation Ce qui est beau à l’intérieur se voit à l’extérieur ! L’émergence de nouveaux métiers LE COMMUNITY MANAGER RH Le sourcing -

For Soft Drinks Players

The Voice of the UK Soft Drinks Industry The British Soft Drinks Association is the national trade association representing the collective interests of producers and manufacturers of soft drinks including carbonated soft drinks, still and dilutable drinks, fruit juices and smoothies, and bottled waters. Join the BSDA today and have your say in your industry! ,QÀXHQFLQJ*RYHUQPHQW Communicating with the Media Promoting Sustainablity Enhancing Skills ,I\RXZLVKWRUHFHLYHIXUWKHULQIRUPDWLRQDERXWDOOWKHEHQH¿WV%6'$PHPEHUVKLS has to offer please call us on +44 (0)207 430 0356 or email [email protected]. Soft Drinks Internationa l – March 2010 ConTEnTS 1 news Europe 4 Africa 8 Middle East 10 The leading English language magazine published in Europe, devoted exclusively to the Asia Pacific 12 manufacture, distribution and marketing of soft drinks, fruit juices and bottled water. Americas 14 Ingredients 18 features Juices & Juice Drinks 22 Energy & Sports 24 Aslanoba Foods Enters The Turkish Juice Market 40 Waters & Water Plus Drinks 26 With the help of Tetra Pak, Teas 29 Aslanoba is on track to reach its target 10% market share bY the end Carbonates 30 of 2010. Traditional 32 Generating Price Premiums 42 Packaging 50 Recent research undertaken bY Quest For New Citrus Notes 34 Beneo-Group has shoWn that price Environment 52 Consumers are looking for neW premiums are still possible if beVerage eXperiences Which are consumers understand and Value People 54 authentic, fresh, Vibrant, sophisticated health benefits. Events 55 and natural, saYs DaWn Streich from GiVaudan. Bubbling Up 57 Clean It Up 44 Implementing an appropriate Water From Flavours To The treatment process can deliVer Tailor-made Product financial and enVironmental gains, regulars Concept 36 maintains Puresep. -

Fizzy Drinks 2014 Data

Soft Drinks Survey 2014 - All Data Data table sorted by category, alphabetically, highest sugar per 100g Product information was collected online, instore or direct from manufacturers Colour coding based on new front of pack traffic Light labelling criteria Sugars - Red >13.5g/portion or >11.25g/100ml, Amber >2.5≤11.25/100ml, Green ≤2.25g/100ml *Serving size has been standardised to 330ml, regular can size. Although many varieties are available in a 330ml can size, some bottles provide 150ml, 250ml or 500ml as a serving size and have been recalculated as 330ml. Product Name Flavour Sugars (g) per 100ml Sugars (g) per 330ml* serving Teaspoons sugar (g) equiv/330ml* serving Fentimans Traditional Curiosity Cola 750ml Cola 11.3 37 9 Best-in American Cola Cola 10.9 36 9 Lidl Freeway Cola Cola 10.9 36 9 Tesco Classic Cola 2 Litre Cola 10.9 36 9 Sainsbury's Classic Cola 2L Cola 10.8 36 9 Marks & Spencer Cola Cola 10.7 35 9 Essential Waitrose Cola 2 litres Cola 10.7 35 9 Asda Chosen by You Cola 2 Litres Cola 10.7 35 9 Coca-Cola 2 Litre Cola 10.6 35 9 Morrisons Cola Cola 10.6 35 9 Pepsi can Cola 10.6 35 9 Aldi VIVE Original Cola Cola 10.6 35 9 Barr Cola 500ml Cola 10.4 34 9 The Co-operative Cola 2 Litre Cola 10.4 34 9 UBUNTU cola Cola 10.4 34 9 Dr Pepper 2 Litre Cola 10.4 34 9 Tesco Original Cola Cola 9.7 32 8 Country Spring Cola 3 Litre Cola 4.8 16 4 Best-in Cola 2 Litre Cola 4 13 3 Barr's Originals Cream Soda with a Twist of Raspberry 330ml Cream Soda 11.5 38 9 Marks & Spencer Cream Soda Cream Soda 10.9 36 9 Waitrose Cream Soda 2 Litres Cream -

Le Duopole Coca-Pepsi

Sommaire Présentation de l’entreprise..............................................................................................................3 Histoire de la société :..................................................................................................................3 Mission :......................................................................................................................................3 Objectif :......................................................................................................................................3 Stratégie :.....................................................................................................................................4 Le microenvironnement...................................................................................................................4 Les fournisseurs...........................................................................................................................4 Les intermédiaires : les sous-traitants, l’internationalisation........................................................5 Les clients....................................................................................................................................6 Concurrence :...............................................................................................................................6 Distributeurs :..............................................................................................................................7 Pepsi-Cola