The Two Aspects of Airline Competition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

Liste-Exploitants-Aeronefs.Pdf

EN EN EN COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, XXX C(2009) XXX final COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No xxx/2009 of on the list of aircraft operators which performed an aviation activity listed in Annex I to Directive 2003/87/EC on or after 1 January 2006 specifying the administering Member State for each aircraft operator (Text with EEA relevance) EN EN COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No xxx/2009 of on the list of aircraft operators which performed an aviation activity listed in Annex I to Directive 2003/87/EC on or after 1 January 2006 specifying the administering Member State for each aircraft operator (Text with EEA relevance) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, Having regard to Directive 2003/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 October 2003 establishing a system for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community and amending Council Directive 96/61/EC1, and in particular Article 18a(3)(a) thereof, Whereas: (1) Directive 2003/87/EC, as amended by Directive 2008/101/EC2, includes aviation activities within the scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community (hereinafter the "Community scheme"). (2) In order to reduce the administrative burden on aircraft operators, Directive 2003/87/EC provides for one Member State to be responsible for each aircraft operator. Article 18a(1) and (2) of Directive 2003/87/EC contains the provisions governing the assignment of each aircraft operator to its administering Member State. The list of aircraft operators and their administering Member States (hereinafter "the list") should ensure that each operator knows which Member State it will be regulated by and that Member States are clear on which operators they should regulate. -

CTA Carriers US DOT Carriers

CTA Carriers The Canadian Transportation Agency (CTA) has defined the application and disclosure of interline baggage rules for travel to or from Canada for tickets issued on or after 1 April 2015. The CTA website offers a list of carriers filing tariffs with the CTA at https://www.otc-cta.gc.ca/eng/carriers-who-file-tariffs-agency. US DOT Carriers The following is a list of carriers that currently file general rule tariffs applicable for travel to/from the United States. This list should be used by subscribers of ATPCO’s Baggage product for determining baggage selection rules for travel to/from the United States. For international journeys to/from the United States, the first marketing carrier’s rules apply. The marketing carrier selected must file general rules tariffs to/from the United States. Systems and data providers should maintain a list based on the carriers listed below to determine whether the first marketing carrier on the journey files tariffs (US DOT carrier). Effective Date: 14AUG17 Code Carrier Code Carrier 2K Aerolineas Galapagos (AeroGal) AA American Airlines 3P Tiara Air Aruba AB Air Berlin 3U Sichuan Airlines AC Air Canada 4C LAN Colombia AD Azul Linhas Aereas Brasileiras 4M LAN Argentina AF Air France 4O ABC Aerolineas S.A. de C.V. AG Aruba Airlines 4V BVI Airways AI Air India 5J Cebu Pacific Air AM Aeromexico 7I Insel Air AR Aerolineas Argentinas 7N Pan American World Airways Dominicana AS Alaska Airlines 7Q Elite Airways LLC AT Royal Air Maroc 8I Inselair Aruba AV Avianca 9V Avoir Airlines AY Finnair 9W Jet Airways AZ Alitalia A3 Aegean Airlines B0 Dreamjet SAS d/b/a La Compagnie Page 1 Revised 31 July 2017 Code Carrier Code Carrier B6 JetBlue Airways GL Air Greenland BA British Airways HA Hawaiian Airlines BE Flybe Group HM Air Seychelles Ltd BG Biman Bangladesh Airlines HU Hainan Airlines BR Eva Airways HX Hong Kong Airlines Limited BT Air Baltic HY Uzbekistan Airways BW Caribbean Airlines IB Iberia CA Air China IG Meridiana CI China Airlines J2 Azerbaijan Airways CM Copa Airlines JD Beijing Capital Airlines Co., Ltd. -

Commission Decision of 14 August 1998 On

21.5.1999 EN Official Journal of the European Communities L 128/1 II (Acts whose publication is not obligatory) COMMISSION COMMISSION DECISION of 14 August 1998 on aid granted by Greece to Olympic Airways (notified under document number C(1998) 2423) (Only the Greek text is authentic) (Text with EEA relevance) (1999/332/EC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN market and the Agreement on the European COMMUNITIES, Economic Area (the EEA Agreement') by virtue of Article 92(3)(c) of the Treaty and of Article 61(3)(c) of the EEA Agreement. The aid Having regard tothe Treaty establishing the European comprised: Community, and in particular the first subparagraph of Article 93(2) thereof, (a) loan guarantees extended to the company Having regard to the Agreement on the European until then pursuant toArticle 6 ofGreek Economic Area, and in particular point (a) of Article Law No96/75 of26 June 1975; 62(1) thereof, (b) new loan guarantees totalling USD 378 Having given the parties concerned notice (1), in million for loans to be contracted before 31 accordance with the provisions of the abovementioned December 1997 for the purchase of new Articles, tosubmit their comments,and having regard aircraft; to those comments, (c) easing of the undertaking's debt burden by Whereas: GRD 427 billion; (d) conversion of GRD 64 billion of the undertaking's debt toequity; THE FACTS I (e) a capital injection of GRD 54 billion in three instalments of GRD 19, 23 and 12 billion in 1995, 1996 and 1997 respectively. (1) On 7 October 1994, the Commission adopted Decision 94/696/EC on the aid granted by Greece toOlympic Airways ( 2) (hereinafter the initial Decison' according to which the aid (2) The last four of these five measures formed part granted and tobe granted by Greece toOlympic of a restructuring and recapitalisation plan for Airways (OA') is compatible with the common OA which had initially been submitted tothe Commission. -

CORSIA Aeroplane Operator to State Attributions

CORSIA Aeroplane Operator to State Attributions This is a preliminary version of the ICAO document “CORSIA Aeroplane Operator to State Attributions” that has been prepared to support the timely implementation of CORSIA from 1 January 2019. It contains aeroplane operators with international flights, and to which State they are attributed, based on information reported by States by 30 November 2018 in accordance with the Environmental Technical Manual (Doc 9501), Volume IV – Procedures for Demonstrating Compliance with the CORSIA, Chapter 3, Table 3-1. Terms used in the tables on the following pages are: • Aeroplane Operator Name is the full name of the aeroplane operator as reported by the State; • Attribution Method is one of three options as selected by the State: "ICAO Designator", "Air Operator Certificate" or "Place of Juridical Registration" in accordance with Annex 16 – Environmental Protection, Volume IV – Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), Part II, Chapter 1, 1.2.4; and • Identifier is associated with each Attribution Method as reported by the State: o If the Attribution Method is "ICAO Designator", the Identifier is the aeroplane operator's three-letter designator according to ICAO Doc 8585; o If the Attribution Method is "Air Operator Certificate", the Identifier is the number of the AOC (or equivalent) of the aeroplane operator; o If the Attribution Method is "Place of Juridical Registration", the Identifier is the name of the State where the aeroplane operator is registered as juridical person. Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of the material presented herein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of ICAO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Facts & Figures & Figures

OCTOBER 2019 FACTS & FIGURES & FIGURES THE STAR ALLIANCE NETWORK RADAR The Star Alliance network was created in 1997 to better meet the needs of the frequent international traveller. MANAGEMENT INFORMATION Combined Total of the current Star Alliance member airlines: FOR ALLIANCE EXECUTIVES Total revenue: 179.04 BUSD Revenue Passenger 1,739,41 bn Km: Daily departures: More than Annual Passengers: 762,27 m 19,000 Countries served: 195 Number of employees: 431,500 Airports served: Over 1,300 Fleet: 5,013 Lounges: More than 1,000 MEMBER AIRLINES Aegean Airlines is Greece’s largest airline providing at its inception in 1999 until today, full service, premium quality short and medium haul services. In 2013, AEGEAN acquired Olympic Air and through the synergies obtained, network, fleet and passenger numbers expanded fast. The Group welcomed 14m passengers onboard its flights in 2018. The Company has been honored with the Skytrax World Airline award, as the best European regional airline in 2018. This was the 9th time AEGEAN received the relevant award. Among other distinctions, AEGEAN captured the 5th place, in the world's 20 best airlines list (outside the U.S.) in 2018 Readers' Choice Awards survey of Condé Nast Traveler. In June 2018 AEGEAN signed a Purchase Agreement with Airbus, for the order of up to 42 new generation aircraft of the 1 MAY 2019 FACTS & FIGURES A320neo family and plans to place additional orders with lessors for up to 20 new A/C of the A320neo family. For more information please visit www.aegeanair.com. Total revenue: USD 1.10 bn Revenue Passenger Km: 11.92 m Daily departures: 139 Annual Passengers: 7.19 m Countries served: 44 Number of employees: 2,498 Airports served: 134 Joined Star Alliance: June 2010 Fleet size: 49 Aircraft Types: A321 – 200, A320 – 200, A319 – 200 Hub Airport: Athens Airport bases: Thessaloniki, Heraklion, Rhodes, Kalamata, Chania, Larnaka Current as of: 14 MAY 19 Air Canada is Canada's largest domestic and international airline serving nearly 220 airports on six continents. -

EU Competition Report Q3

EU Competition Report JULY – SEPTEMBER 2010 www.clearygottlieb.com HORIZONTAL AGREEMENTS cartel, and the attribution of liability among the various companies of the same group), together with supporting evidence. Immediately Commission decisions afterwards, the Commission granted each party access (at the DRAM Cartel Commission’s premises) to a selection of key documents from the On May 19, 2010, the European Commission issued its long-awaited case file, including all leniency statements. Parties were also invited first cartel settlement decision (the first since the Commission to comment on the Commission’s allegations at this stage. 1 introduced the settlement procedure in June 2008). The settlement • During the second meeting the Commission provided parties with decision imposed a total of €331,273,800 in fines on ten producers of feedback on their arguments and observations submitted following Dynamic Random Access Memory (“DRAM”) chips that were found to the first meeting and partial file access. have participated in cartel conduct in violation of Article 101 TFEU. Between July 1, 1998, and June 15, 2002, the cartel participants • Finally, during a third meeting the Commission disclosed to each engaged in a network of mostly bilateral contacts through which they party the range within which its fine would ultimately fall, without exchanged pricing information and coordinated prices and quotations disclosing methodology that the Commission intended to use to for DRAM sold to major PC or server manufacturers in the EEA. All calculate the actual fine. participants agreed to follow the settlement procedure and received a Following the third settlement meeting, the Commission set a time limit 2 10% settlement discount as provided by the Settlement Notice. -

08-06-2021 Airline Ticket Matrix (Doc 141)

Airline Ticket Matrix 1 Supports 1 Supports Supports Supports 1 Supports 1 Supports 2 Accepts IAR IAR IAR ET IAR EMD Airline Name IAR EMD IAR EMD Automated ET ET Cancel Cancel Code Void? Refund? MCOs? Numeric Void? Refund? Refund? Refund? AccesRail 450 9B Y Y N N N N Advanced Air 360 AN N N N N N N Aegean Airlines 390 A3 Y Y Y N N N N Aer Lingus 053 EI Y Y N N N N Aeroflot Russian Airlines 555 SU Y Y Y N N N N Aerolineas Argentinas 044 AR Y Y N N N N N Aeromar 942 VW Y Y N N N N Aeromexico 139 AM Y Y N N N N Africa World Airlines 394 AW N N N N N N Air Algerie 124 AH Y Y N N N N Air Arabia Maroc 452 3O N N N N N N Air Astana 465 KC Y Y Y N N N N Air Austral 760 UU Y Y N N N N Air Baltic 657 BT Y Y Y N N N Air Belgium 142 KF Y Y N N N N Air Botswana Ltd 636 BP Y Y Y N N N Air Burkina 226 2J N N N N N N Air Canada 014 AC Y Y Y Y Y N N Air China Ltd. 999 CA Y Y N N N N Air Choice One 122 3E N N N N N N Air Côte d'Ivoire 483 HF N N N N N N Air Dolomiti 101 EN N N N N N N Air Europa 996 UX Y Y Y N N N Alaska Seaplanes 042 X4 N N N N N N Air France 057 AF Y Y Y N N N Air Greenland 631 GL Y Y Y N N N Air India 098 AI Y Y Y N N N N Air Macau 675 NX Y Y N N N N Air Madagascar 258 MD N N N N N N Air Malta 643 KM Y Y Y N N N Air Mauritius 239 MK Y Y Y N N N Air Moldova 572 9U Y Y Y N N N Air New Zealand 086 NZ Y Y N N N N Air Niugini 656 PX Y Y Y N N N Air North 287 4N Y Y N N N N Air Rarotonga 755 GZ N N N N N N Air Senegal 490 HC N N N N N N Air Serbia 115 JU Y Y Y N N N Air Seychelles 061 HM N N N N N N Air Tahiti 135 VT Y Y N N N N N Air Tahiti Nui 244 TN Y Y Y N N N Air Tanzania 197 TC N N N N N N Air Transat 649 TS Y Y N N N N N Air Vanuatu 218 NF N N N N N N Aircalin 063 SB Y Y N N N N Airlink 749 4Z Y Y Y N N N Alaska Airlines 027 AS Y Y Y N N N Alitalia 055 AZ Y Y Y N N N All Nippon Airways 205 NH Y Y Y N N N N Amaszonas S.A. -

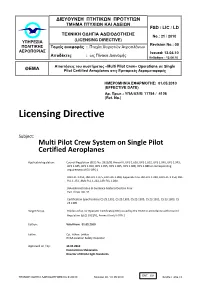

Licensing Directive)

∆ΙΕΥΘΥΝΣΗ ΠΤΗΤΙΚΩΝ ΠΡΟΤΥΠΩΝ ΤΜΗΜΑ ΠΤΥΧΙΩΝ ΚΑΙ Α∆ΕΙΩΝ FSD / LIC / LD ΤΕΧΝΙΚΗ Ο∆ΗΓΙΑ Α∆ΕΙΟ∆ΟΤΗΣΗΣ No.: 21 / 2010 (LICENSING DIRECTIVE) ΥΠΗΡΕΣΙΑ Revision No.: 00 ΠΟΛΙΤΙΚΗΣ Τοµείς αναφοράς : Πτυχία Χειριστών Αεροπλάνων ΑΕΡΟΠΟΡΙΑΣ Issued: 13.04.10 Αποδέκτες : ως Πίνακα ∆ιανοµής Εκδόθηκε : 13.04.10 Απαιτήσεις του συστήµατος «Multi Pilot Crew» Operations σε Single ΘΕΜΑ Pilot Certified Aeroplanes στις Εµπορικές Αεροµεταφορές ΗΜΕΡΟΜΗΝΙΑ ΕΦΑΡΜΟΓΗΣ : 01.05.2010 (EFFECTIVE DATE) Αρ . Πρωτ .: ΥΠΑ /∆2/ Β/ 11754 / 4126 (Ref. No.) Licensing Directive Subject: Multi Pilot Crew System on Single Pilot Certified Aeroplanes Applicable legislation: Council Regulation (EEC) No. 3922/91 Annex III, OPS 1.650, OPS 1.652, OPS 1.940, OPS 1.943, OPS 1.945, OPS 1.950, OPS 1.955, OPS 1.965, OPS 1.968, OPS 1.980 or corresponding requirement of EU-OPS 1 JAR-FCL 1.050, JAR-FCL 1.075, JAR-FCL 1.080, Appendix 1 to JAR-FCL 1.220, JAR-FCL 1.250, JAR- FCL 1.251, AMC FCL 1.261, JAR-FCL 1.280 JAA Administrative & Guidance Material Section Four Part Three TGL 44 Certification Specifications CS 25.1301, CS 25.1303, CS 25.1305, CS 23.1301, CS 23.1303, CS 23.1305 Target Group: Holders of an Air Operator Certificate (AOC) issued by the HCAA in accordance with Council Regulation (EEC) 3922/91, Annex III or EU-OPS 1 Edition: Valid from: 01.05.2010 Editor: Cpt. Athan. Lekkas HCAA Aviation Safety Inspector Approved on / by: 13.04.2010 Konstantinos Sfakianakis Director of HCAA Flight Standards ΕΝΤ. : 633 ΤΕΧΝΙΚΗ Ο∆ΗΓΙΑ Α∆ΕΙΟ∆ΟΤΗΣΗΣ Νο 21/2010 Revision 00 / 01.05.2010 Σελίδα 1 από 13 Summary 0. -

DHL and Leipzig Now Lead ATM Stats 3 European Airline Operations in April According to Eurocontrol

Issue 56 Monday 20 April 2020 www.anker-report.com Contents C-19 wipes out 95% of April air traffic; 1 C-19 wipes out 95% of April air traffic; DHL and Leipzig now lead movements statistics in Europe. DHL and Leipzig now lead ATM stats 3 European airline operations in April according to Eurocontrol. The coronavirus pandemic has managed in the space of a According to the airline’s website, Avinor has temporarily month to reduce European air passenger travel from roughly its closed nine Norwegian airports to commercial traffic and 4 Alitalia rescued (yet again) by Italian normal level (at the beginning of March) to being virtually non- Widerøe has identified alternatives for all of them, with bus government; most international existent (at the end of March). Aircraft movement figures from transport provided to get the passengers to their required routes from Rome face intense Eurocontrol show the rapid decrease in operations during the destination. competition; dominant at Milan LIN. month. By the end of the month, flights were down around Ryanair still connecting Ireland and the UK 5 Round-up of over 300 new routes 90%, but many of those still operating were either pure cargo flights (from the likes of DHL and FedEx), or all-cargo flights Ryanair’s current operating network comprises 13 routes from from over 60 airlines that were being operated by scheduled airlines. Ireland, eight of which are to the UK (from Dublin to supposed to have launched during Birmingham, Bristol, Edinburgh, Glasgow, London LGW, London the last five weeks involving Leipzig/Halle is now Europe’s busiest airport STN and Manchester as well as Cork to London STN). -

STAR ALLIANCE to ESTABLISH CENTRE of EXCELLENCE in SINGAPORE New Setup Reflects Global Character of the Alliance

STAR ALLIANCE TO ESTABLISH CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE IN SINGAPORE New setup reflects global character of the Alliance FRANKFURT – March 22, 2021 – Star Alliance will establish a management office in the city state of Singapore later this year. This was a decision taken by its Chief Executive Board, comprising the Chief Executive Officers of its 26 member airlines, who considered a new centre of excellence to be an important dimension of positioning the Alliance to deliver on its post-Coronavirus strategy, and for it to remain innovative, resilient and nimble. All businesses are reimagining a post-pandemic world fundamentally changed by COVID-19, and the associated disruption to global networks, economies, and the livelihoods of many. A consequence of the world’s reaction to COVID-19 has been the destabilizing effect it has had on aviation. This decision to future-proof the Alliance was made against this backdrop. Effectively, Star Alliance will maintain two centres of excellence internationally, in keeping with the global character of the Alliance. The Singapore office will complement the long-standing office in Frankfurt, Germany and will focus on progressing its strategy in digital customer experience. Two members of the Alliance, Lufthansa and Singapore Airlines, have established innovation hubs in the City, another benefit as the Alliance continues its ground-breaking digital customer experience innovations. Singapore was selected based on considered criteria, such as access to innovation and global competitiveness. Singapore has also been ranked highly for the ease of doing business by the World Bank on a consistent basis and has been ranked the most competitive country in the world on several occasions. -

356 Partners Found. Check If Available in Your Market

367 partners found. Check if available in your market. Please always use Quick Check on www.hahnair.com/quickcheck prior to ticketing P4 Air Peace BG Biman Bangladesh Airl… T3 Eastern Airways 7C Jeju Air HR-169 HC Air Senegal NT Binter Canarias MS Egypt Air JQ Jetstar Airways A3 Aegean Airlines JU Air Serbia 0B Blue Air LY EL AL Israel Airlines 3K Jetstar Asia EI Aer Lingus HM Air Seychelles BV Blue Panorama Airlines EK Emirates GK Jetstar Japan AR Aerolineas Argentinas VT Air Tahiti OB Boliviana de Aviación E7 Equaflight BL Jetstar Pacific Airlines VW Aeromar TN Air Tahiti Nui TF Braathens Regional Av… ET Ethiopian Airlines 3J Jubba Airways AM Aeromexico NF Air Vanuatu 1X Branson AirExpress EY Etihad Airways HO Juneyao Airlines AW Africa World Airlines UM Air Zimbabwe SN Brussels Airlines 9F Eurostar RQ Kam Air 8U Afriqiyah Airways SB Aircalin FB Bulgaria Air BR EVA Air KQ Kenya Airways AH Air Algerie TL Airnorth VR Cabo Verde Airlines FN fastjet KE Korean Air 3S Air Antilles AS Alaska Airlines MO Calm Air FJ Fiji Airways KU Kuwait Airways KC Air Astana AZ Alitalia QC Camair-Co AY Finnair B0 La Compagnie UU Air Austral NH All Nippon Airways KR Cambodia Airways FZ flydubai LQ Lanmei Airlines BT Air Baltic Corporation Z8 Amaszonas K6 Cambodia Angkor Air XY flynas QV Lao Airlines KF Air Belgium Z7 Amaszonas Uruguay 9K Cape Air 5F FlyOne LA LATAM Airlines BP Air Botswana IZ Arkia Israel Airlines BW Caribbean Airlines FA FlySafair JJ LATAM Airlines Brasil 2J Air Burkina OZ Asiana Airlines KA Cathay Dragon GA Garuda Indonesia XL LATAM Airlines