Name”: Name (Ming 名) As Prime Mover of Political Action in Early China* Yuri Pines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Philosophy

CHINESE PHILOSOPHY Vatican Relations: Problems of Conflicting Authority, 1976–1986 EARLY HISTORY (Cambridge 1992). J. LEUNG, Wenhua Jidutu: Xianxiang yu lunz- heng (Cultural Christian: Phenomenon and Argument) (Hong Shang Dynasty (c.1600–c.1045 B.C.). Chinese Kong 1997). K. C. LIU, ed. American Missionaries in China: Papers philosophical thought took definite shape during the reign from Harvard Seminars (Cambridge 1966). Lutheran World Feder- of the Shang dynasty in Bronze Age China. During this ation/Pro Mundi Vita. Christianity and the New China (South Pasa- period, the primeval forms of ancestor veneration in Neo- dena 1976). L. T. LYALL, New Spring in China? (London 1979). J. G. LUTZ, ed. Christian Missions in China: Evangelist of What? lithic Chinese cultures had evolved to relatively sophisti- (Boston 1965). D. E. MACINNIS, Religion in China Today: Policy cated rituals that the Shang ruling house offered to their and Practice (Maryknoll, NY 1989). D. MACINNIS and X. A. ZHENG, ancestors and to Shangdi, the supreme deity who was a Religion under Socialism in China (Armonk, NY 1991). R. MAD- deified ancestor and progenitor of the Shang ruling fami- SEN, China Catholics: Tragedy and Hope in an Emerging Civil So- ciety (Berkeley 1998). R. MALEK and M. PLATE Chinas Katholiken ly. A class of shamans emerged, tasked with divination suchen neue (Freiburg 1987). Missiones Catholicae cura S. Con- and astrology using oracle bones for the benefit of the rul- gregationis de Propaganda Fide descriptae statistica (Rome 1901, ing class. Archaeological excavations have uncovered 1907, 1922, 1927). J. METZLER, ed. Sacrae Congregationis de Pro- elaborate bronze sacrificial vessels and other parapherna- paganda Fide Memoria Rerum, 1622–1972 (Rome 1976). -

The Zhuan Xupeople Were the Founders of Sanxingdui Culture and Earliest Inhabitants of South Asia

E-Leader Bangkok 2018 The Zhuan XuPeople were the Founders of Sanxingdui Culture and Earliest Inhabitants of South Asia Soleilmavis Liu, Author, Board Member and Peace Sponsor Yantai, Shangdong, China Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas) records many ancient groups of people (or tribes) in Neolithic China. The five biggest were: Zhuan Xu, Di Jun, Huang Di, Yan Di and Shao Hao.However, the Zhuan Xu People seemed to have disappeared when the Yellow and Chang-jiang river valleys developed into advanced Neolithic cultures. Where had the Zhuan Xu People gone? Abstract: Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas) records many ancient groups of people in Neolithic China. The five biggest were: Zhuan Xu, Di Jun, Huang Di, Yan Di and Shao Hao. These were not only the names of individuals, but also the names of groups who regarded them as common male ancestors. These groups used to live in the Pamirs Plateau, later spread to other places of China and built their unique ancient cultures during the Neolithic Age. Shanhaijing reveals Zhuan Xu’s offspring lived near the Tibetan Plateau in their early time. They were the first who entered the Tibetan Plateau, but almost perished due to the great environment changes, later moved to the south. Some of them entered the Sichuan Basin and became the founders of Sanxingdui Culture. Some of them even moved to the south of the Tibetan Plateau, living near the sea. Modern archaeological discoveries have revealed the authenticity of Shanhaijing ’s records. Keywords: Shanhaijing; Neolithic China, Zhuan Xu, Sanxingdui, Ancient Chinese Civilization Introduction Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas) records many ancient groups of people in Neolithic China. -

The Old Master

INTRODUCTION Four main characteristics distinguish this book from other translations of Laozi. First, the base of my translation is the oldest existing edition of Laozi. It was excavated in 1973 from a tomb located in Mawangdui, the city of Changsha, Hunan Province of China, and is usually referred to as Text A of the Mawangdui Laozi because it is the older of the two texts of Laozi unearthed from it.1 Two facts prove that the text was written before 202 bce, when the first emperor of the Han dynasty began to rule over the entire China: it does not follow the naming taboo of the Han dynasty;2 its handwriting style is close to the seal script that was prevalent in the Qin dynasty (221–206 bce). Second, I have incorporated the recent archaeological discovery of Laozi-related documents, disentombed in 1993 in Jishan District’s tomb complex in the village of Guodian, near the city of Jingmen, Hubei Province of China. These documents include three bundles of bamboo slips written in the Chu script and contain passages related to the extant Laozi.3 Third, I have made extensive use of old commentaries on Laozi to provide the most comprehensive interpretations possible of each passage. Finally, I have examined myriad Chinese classic texts that are closely associated with the formation of Laozi, such as Zhuangzi, Lüshi Chunqiu (Spring and Autumn Annals of Mr. Lü), Han Feizi, and Huainanzi, to understand the intellectual and historical context of Laozi’s ideas. In addition to these characteristics, this book introduces several new interpretations of Laozi. -

Parte I €“ Dilema éTico Y Virtud

Virtud y consecuencia en la literatura histórica y filosófica pre-Han y Han: el dilema ético en la filosofía y sociedad china César Guarde Paz ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tdx.cat) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tdx.cat) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. -

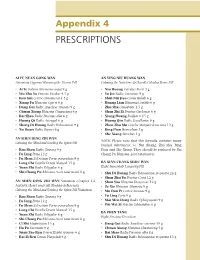

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS AI FU NUAN GONG WAN AN YING NIU HUANG WAN Artemisia-Cyperus Warming the Uterus Pill Calming the Nutritive-Qi [Level] Calculus Bovis Pill • Ai Ye Folium Artemisiae argyi 9 g • Niu Huang Calculus Bovis 3 g • Wu Zhu Yu Fructus Evodiae 4.5 g • Yu Jin Radix Curcumae 9 g • Rou Gui Cortex Cinnamomi 4.5 g • Shui Niu Jiao Cornu Bubali 6 g • Xiang Fu Rhizoma Cyperi 9 g • Huang Lian Rhizoma Coptidis 6 g • Dang Gui Radix Angelicae sinensis 9 g • Zhu Sha Cinnabaris 1.5 g • Chuan Xiong Rhizoma Chuanxiong 6 g • Shan Zhi Zi Fructus Gardeniae 6 g • Bai Shao Radix Paeoniae alba 6 g • Xiong Huang Realgar 0.15 g • Huang Qi Radix Astragali 6 g • Huang Qin Radix Scutellariae 9 g • Sheng Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae 9 g • Zhen Zhu Mu Concha Margatiriferae usta 12 g • Xu Duan Radix Dipsaci 6 g • Bing Pian Borneolum 3 g • She Xiang Moschus 1 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN NOTE: Please note that this formula contains many Calming the Mind and Settling the Spirit Pill banned substances, i.e. Niu Huang, Zhu Sha, Bing • Ren Shen Radix Ginseng 9 g Pian and She Xiang. They should be replaced by Shi • Fu Ling Poria 12 g Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii. • Fu Shen Sclerotium Poriae pararadicis 9 g • Long Chi Fossilia Dentis Mastodi 15 g BA XIAN CHANG SHOU WAN • Yuan Zhi Radix Polygalae 6 g Eight Immortals Longevity Pill • Shi Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii 8 g • Shu Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae preparata 24 g • Shan Zhu Yu Fructus Corni 12 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN Variation (Chapter 14, • Shan Yao Rhizoma Dioscoreae 12 g Anxiety, Heart and Gall Bladder -

Reimagining Revolutionary Labor in the People's Commune

Reimagining Revolutionary Labor in the People’s Commune: Amateurism and Social Reproduction in the Maoist Countryside by Angie Baecker A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Asian Languages and Cultures) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Xiaobing Tang, Co-Chair, Chinese University of Hong Kong Associate Professor Emily Wilcox, Co-Chair Professor Geoff Eley Professor Rebecca Karl, New York University Associate Professor Youngju Ryu Angie Baecker [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0182-0257 © Angie Baecker 2020 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my grandmother, Chang-chang Feng 馮張章 (1921– 2016). In her life, she chose for herself the penname Zhang Yuhuan 張宇寰. She remains my guiding star. ii Acknowledgements Nobody writes a dissertation alone, and many people’s labor has facilitated my own. My scholarship has been borne by a great many networks of support, both formal and informal, and indeed it would go against the principles of my work to believe that I have been able to come this far all on my own. Many of the people and systems that have enabled me to complete my dissertation remain invisible to me, and I will only ever be able to make a partial account of all of the support I have received, which is as follows: Thanks go first to the members of my committee. To Xiaobing Tang, I am grateful above all for believing in me. Texts that we have read together in numerous courses and conversations remain cornerstones of my thinking. He has always greeted my most ambitious arguments with enthusiasm, and has pushed me to reach for higher levels of achievement. -

Foreigners and Propaganda War and Peace in the Imperial Images of Augustus and Qin Shi Huangdi

Foreigners and Propaganda War and Peace in the Imperial Images of Augustus and Qin Shi Huangdi This thesis is presented by Dan Qing Zhao (317884) to the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the field of Classics in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies Faculty of Arts University of Melbourne Principal Supervisor: Dr Hyun Jin Kim Secondary Supervisor: Associate Professor Frederik J. Vervaet Submission Date: 20/07/2018 Word Count: 37,371 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements i Translations and Transliterations ii Introduction 1 Current Scholarship 2 Methodology 7 Sources 13 Contention 19 Chapter One: Pre-Imperial Attitudes towards Foreigners, Expansion, and Peace in Early China 21 Western Zhou Dynasty and Early Spring and Autumn Period (11th – 6th century BCE) 22 Late Spring and Autumn Period (6th century – 476 BCE) 27 Warring States Period (476 – 221 BCE) 33 Conclusion 38 Chapter Two: Pre-Imperial Attitudes towards Foreigners, Expansion, and Peace in Rome 41 Early Rome (Regal Period to the First Punic War, 753 – 264 BCE) 42 Mid-Republic (First Punic War to the End of the Macedonian Wars, 264 – 148 BCE) 46 Late Republic (End of the Macedonian Wars to the Second Triumvirate, 148 – 43 BCE) 53 Conclusion 60 Chapter Three: Peace through Warfare 63 Qin Shi Huangdi 63 Augustus 69 Conclusion 80 Chapter Four: Morality, Just War, and Universal Consensus 82 Qin Shi Huangdi 82 Augustus 90 Conclusion 104 Chapter Five: Victory and Divine Support 106 Qin Shi Huangdi 108 Augustus 116 Conclusion 130 Conclusion 132 Bibliography 137 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to offer my sincerest thanks to Dr Hyun Jin Kim. -

Empresses, Bhikṣuṇῑs, and Women of Pure Faith

EMPRESSES, BHIKṢUṆῙS, AND WOMEN OF PURE FAITH EMPRESSES, BHIKṢUṆῙS, AND WOMEN OF PURE FAITH: BUDDHISM AND THE POLITICS OF PATRONAGE IN THE NORTHERN WEI By STEPHANIE LYNN BALKWILL, B.A. (High Honours), M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © by Stephanie Lynn Balkwill, July 2015 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2015) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Empresses, Bhikṣuṇīs, and Women of Pure Faith: Buddhism and the Politics of Patronage in the Northern Wei AUTHOR: Stephanie Lynn Balkwill, B.A. (High Honours) (University of Regina), M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. James Benn NUMBER OF PAGES: x, 410. ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is a study of the contributions that women made to the early development of Chinese Buddhism during the Northern Wei Dynasty 北魏 (386–534 CE). Working with the premise that Buddhism was patronized as a necessary, secondary arm of government during the Northern Wei, the argument put forth in this dissertation is that women were uniquely situated to play central roles in the development, expansion, and policing of this particular form of state-sponsored Buddhism due to their already high status as a religious elite in Northern Wei society. Furthermore, in acting as representatives and arbiters of this state-sponsored Buddhism, women of the Northern Wei not only significantly contributed to the spread of Buddhism throughout East Asia, but also, in so doing, they themselves gained increased social mobility and enhanced social status through their affiliation with the new, foreign, and wildly popular Buddhist tradition. -

The Power of an Alleged Tradition: a Prophecy Flattering Han Emperor Wu and Its Relation to the Sima Clan*

The Power of an Alleged Tradition: A Prophecy Flattering Han Emperor Wu and its Relation to the Sima Clan* by Dorothee Schaab-Hanke . es muß stets eine lange Übermittlerkette vorhanden sein, damit sich die Hinweise oder Gedanken, die Kommentare, wie immer man es nennt, dehnen. Sie müsen durch zehn Hirne hindurch, um einen Satz zu ergeben.** (Alexander Kluge) Introduction During the early reign of Liu Che ᄸ, posthumously honored as Emperor Wu r. 141–87) of the Han, a severe struggle for infl uence and power seems to) ܹن have arisen among competing groups of experts concerned with the establishment of new imperial rites. This is at least the impression that the Shiji͑৩ (The Scribe’s Record) conveys to the reader in chapter 28, the “Treatise on the Feng and Shan Sacrifi ces” (Fengshan shuܱᑐए). According to the account given there, the compet- ing partners in this struggle were mainly the ru ኵ (here used in the sense of scholars who maintained that any advice in the question of ritual should entirely be based upon evidence drawn from the “Classics”) and a group of specialists called fangshī ʦ (a term which should be translated by “masters of techniques” rather than by the often used, but rather biased term magicians). * I am indebted to Prof. Dr. Hans Stumpfeldt (Hamburg), Dr. Achim Mittag (Essen) and Dr. Monique Nagel- Angermann (Münster) for their helpful and inspiring comments on the text. Special thanks to Dr. Martin Svens- son Ekström (Stockholm), Prof. Dr. E. Bruce Brooks and Dr. A. Taeko Brooks (Amherst, Mass.) as well as two anonymous readers for the BMFEA for their competent and engaged revising of the draft. -

Weaponry During the Period of Disunity in Imperial China with a Focus on the Dao

Weaponry During the Period of Disunity in Imperial China With a focus on the Dao An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty Of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE By: Bryan Benson Ryan Coran Alberto Ramirez Date: 04/27/2017 Submitted to: Professor Diana A. Lados Mr. Tom H. Thomsen 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 List of Figures 4 Individual Participation 7 Authorship 8 1. Abstract 10 2. Introduction 11 3. Historical Background 12 3.1 Fall of Han dynasty/ Formation of the Three Kingdoms 12 3.2 Wu 13 3.3 Shu 14 3.4 Wei 16 3.5 Warfare and Relations between the Three Kingdoms 17 3.5.1 Wu and the South 17 3.5.2 Shu-Han 17 3.5.3 Wei and the Sima family 18 3.6 Weaponry: 18 3.6.1 Four traditional weapons (Qiang, Jian, Gun, Dao) 18 3.6.1.1 The Gun 18 3.6.1.2 The Qiang 19 3.6.1.3 The Jian 20 3.6.1.4 The Dao 21 3.7 Rise of the Empire of Western Jin 22 3.7.1 The Beginning of the Western Jin Empire 22 3.7.2 The Reign of Empress Jia 23 3.7.3 The End of the Western Jin Empire 23 3.7.4 Military Structure in the Western Jin 24 3.8 Period of Disunity 24 4. Materials and Manufacturing During the Period of Disunity 25 2 Table of Contents (Cont.) 4.1 Manufacturing of the Dao During the Han Dynasty 25 4.2 Manufacturing of the Dao During the Period of Disunity 26 5. -

The “Masters” in the Shiji

T’OUNG PAO T’oungThe “Masters” Pao 101-4-5 in (2015) the Shiji 335-362 www.brill.com/tpao 335 The “Masters” in the Shiji Martin Kern (Princeton University) Abstract The intellectual history of the ancient philosophical “Masters” depends to a large extent on accounts in early historiography, most importantly Sima Qian’s Shiji which provides a range of longer and shorter biographies of Warring States thinkers. Yet the ways in which personal life experiences, ideas, and the creation of texts are interwoven in these accounts are diverse and uneven and do not add up to a reliable guide to early Chinese thought and its protagonists. In its selective approach to different thinkers, the Shiji under-represents significant parts of the textual heritage while developing several distinctive models of authorship, from anonymous compilations of textual repertoires to the experience of personal hardship and political frustration as the precondition for turning into a writer. Résumé L’histoire intellectuelle des “maîtres” de la philosophie chinoise ancienne dépend pour une large part de ce qui est dit d’eux dans l’historiographie ancienne, tout particulièrement le Shiji de Sima Qian, qui offre une série de biographies plus ou moins étendues de penseurs de l’époque des Royaumes Combattants. Cependant leur vie, leurs idées et les conditions de création de leurs textes se combinent dans ces biographies de façon très inégale, si bien que l’ensemble ne saurait être considéré comme l’équivalent d’un guide de la pensée chinoise ancienne et de ses auteurs sur lequel on pourrait s’appuyer en toute confiance. -

The Influence of the Translator's Culture On

THE INFLUENCE OF THE TRANSLATOR’S CULTURE ON THE TRANSLATION OF SELECTED RHETORICAL DEVICES IN CONFUCIUS’ ANALECTS by CHEN-SHU FANG A dissertation submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master’s in Language Practice Department of Linguistics and Language Practice Faculty of the Humanities University of the Free State January 2016 Supervisor: Prof. K. Marais External co-supervisor: Prof. Y. Ma i DECLARATION I, Chen-Shu Fang, hereby declare that this dissertation submitted by me for a Master’s degree in Language Practice at the University of the Free State is my own independent work that has not previously been submitted by me at another university or faculty. Furthermore, I do cede copyright of this dissertation in favour of the University of the Free State. Signature Date ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I wish to express my immense gratitude to the Almighty God for making this dissertation possible by providing me with wisdom, good health, courage, knowledgeable supervisors and a supportive family. I feel a deep sense of gratitude to the following people who contributed to the preparation and production of this dissertation: I want to sincerely thank Prof. Kobus Marais, my supervisor, for his support, warm-hearted encouragement, invaluable advice and informative suggestions throughout this project. Without his input, completing this dissertation would have been impossible. I admire his knowledge and personality. His character guided me throughout the writing process. I am also grateful to Prof. Yue Ma, my co-supervisor, for his good advice, assistance and insightful comments, especially about the cultural and rhetorical parts of the study.