Nature and Ideology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1 the Development of Landscape Architecture

Revisiting Riverside: A Frederick Law Olmsted Community Chapter 1 The Development of Landscape Architecture Landscape Architecture is a profession that involves human interaction with nature. It entails human impacts upon the land, such as the shaping of landform and the creation of parks, urban spaces, and gardens. Landscape architecture can also include the mitigation of human impacts upon nature. For example, landscape architects are often involved with the restoration of or preservation of areas for wildlife and for the continued success of natural processes (i.e. stormwater collection and purification, groundwater recharge, water quality, the survival of native plants and plant communities, etc.). Landscape architecture is often inspired by social needs. Olmsted’s work was a reaction to the uncleanly, overcrowded conditions of cities in the late nineteenth-century and the need for people to escape from these conditions and restore themselves in a natural setting. This same ethic inspires many of today’s landscape architects who seek to provide safe, inviting parks within cities and to develop housing that responds to the needs of the residents. This housing could be in the form of improved public housing, developed through dialog with residents and informed by the successes and failures of past public housing trends. Landscape Architect’s involvement with planning efforts range from complex and inspired plans such as Riverside in 1868 - 1869, Garden Cities (Radburn, NJ 1928), the Greenbelt town design of the 1930s, and today’s ecologically and culturally sensitive development models, to the typical, ubiquitous, suburban developments that have evolved since the early twentieth century. The scope of landscape architecture ranges from broad projects (town planning and large, national parks) to narrow (small parks, urban plazas, commercial centers and residences). -

Ideas and Tradition Behind Chinese and Western Landscape Design

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Landscape Planning, Horticulture and Agricultural Science Department of Landscape Architecture Ideas and Tradition behind Chinese and Western Landscape Design - similarities and differences Junying Pang Degree project in landscape planning, 30 hp Masterprogramme Urban Landscape Dynamics Independent project at the LTJ Faculty, SLU Alnarp 2012 1 Idéer och tradition bakom kinesisk och västerländsk landskapsdesign Junying Pang Supervisor: Kenneth Olwig, SLU, Department of Landscape Architecture , , Assistant Supervisor: Anna Jakobsson, SLU, Department of Landscape Architecture , , Examiner: Eva Gustavsson, SLU, Department of Landscape Architecture , , Credits: 30 hp Level: A2E Course title: Degree Project in the Masterprogramme Urban Landscape Dynamics Course code: EX0377 Programme/education: Masterprogramme Urban Landscape Dynamics Subject: Landscape planning Place of publication: Alnarp Year of publication: January 2012 Picture cover: http://photo.zhulong.com/proj/detail4350.htm Series name: Independent project at the LTJ Faculty, SLU Online publication: http://stud.epsilon.slu.se Key Words: Ideas, Tradition, Chinese landscape Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Landscape Planning, Horticulture and Agricultural Science Department of Landscape Architecture 2 Forward This degree project was written by the student from the Urban Landscape Dynamics (ULD) Programme at Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU). This programme is a two years master programme, and it relates to planning and designing of the urban landscape. The level and depth of this degree project is Master E, and the credit is 30 Ects. Supervisor of this degree project has been Kenneth Olwig, professor at the Department of Landscape architecture; assistant supervisor has been Anna Jakobsson, teacher and research assistant at the Department of Landscape architecture; master’s thesis coordinator has been Eva Gustavsson, senior lecturer at the Department of Landscape architecture. -

NJASLA 2014 Awards Program

The New Jersey Chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects is pleased to present the 2014 Professional Awards. The awards program is intended to help broaden the boundaries of our profession; increase public awareness of the role of landscape architects; raise the standards of our discipline; and bring recognition to organizations and individuals who demonstrate superior skill in the practice and study of landscape architecture. A jury of distinguished landscape architects reviewed twenty-one submissions and selected win- ners in fi ve categories. We invite you to view the winning projects throughout the conference on our continuously-running video presentation located on the conference fl oor. The winners will also be featured in upcoming newsletters, our website and other events which promote our profes- sion throughout the state during the course of the year. Thank you for attending this year’s presentation. We hope you enjoy this year’s ceremonies and strongly encourage you to consider submitting your work for next year’s program. Eric Mattes Denise Mattes HONORINGour past 2014 AWARDS JURY EMBRACING Dr. Wolfram Hoefer, Rutgers University our future Wolfram is an Associate Professor at the Department of Landscape Architecture at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey and serves as Undergraduate Program Director for the department. He also serves as Co-Director of the #NJASLA50 Rutgers Center for Urban Environmental Sustainability. In 1992 he earned a Diploma in Landscape Architecture from the Technische Universität Berlin and received a doctoral degree from Technische Universtät München in 2000. He is a licensed Landscape Architect in the state of Bavaria, Germany. -

SULIS: Sustainable Urban Landscape Information Series — Design

AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND NATURAL RESOURCES SULIS: Sustainable Urban Landscape Information Series — Design PARTS IN THIS SERIES SUSTAINABILITY AND LANDSCAPE DESIGN Discusses the major considerations that need to be incorporated into a landscape design if a sustainable landscape is to be the outcome. Landscape functionality, cost effectiveness, and environmental impacts are a few of the items discussed. THE BASE PLAN Describes how information is gathered, compiled and used in the development of a landscape design. How to conduct an interview, carry out a site survey and site analysis, and how to use information collected from counties, municipalities and developers are some of the topics discussed. THE LANDSCAPE DESIGN SEQUENCE Explains the essential steps to create a sustainable landscape design. The design sequence includes the creation of bubble diagrams, concept plans, and draft designs THE COMPLETED LANDSCAPE DESIGN Describes the transition from a draft to the completed landscape design. Important principles and elements of design are defined. Examples of how each is used in the development of a sustainable design are included. © 2018, Regents of the University of Minnesota. University of Minnesota Extension is an equal opportunity educator and employer. In accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, this publication/material is available in alternative formats upon request. Direct requests to 612-624-0772 or [email protected]. SUSTAINABILITY AND LANDSCAPE DESIGN There are five considerations in designing a sustainable landscape. The landscape should be: Visually Pleasing Cost Effective Functional Maintainable Environmentally Sound These considerations are not new nor have they been without considerable discussion. Problems arise, however when some considerations are forgotten or unrecognized until after the design process is complete and implementation has started. -

Anthrozoology and Sharks, Looking at How Human-Shark Interactions Have Shaped Human Life Over Time

Anthrozoology and Public Perception: Humans and Great White Sharks (Carchardon carcharias) on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA Jessica O’Toole A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Marine Affairs University of Washington 2020 Committee: Marc L. Miller, Chair Vincent F. Gallucci Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Marine and Environmental Affairs © Copywrite 2020 Jessica O’Toole 2 University of Washington Abstract Anthrozoology and Public Perception: Humans and Great White Sharks (Carchardon carcharias) on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA Jessica O’Toole Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Marc L. Miller School of Marine and Environmental Affairs Anthrozoology is a relatively new field of study in the world of academia. This discipline, which includes researchers ranging from social studies to natural sciences, examines human-animal interactions. Understanding what affect these interactions have on a person’s perception of a species could be used to create better conservation strategies and policies. This thesis uses a mixed qualitative methodology to examine the public perception of great white sharks on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. While the area has a history of shark interactions, a shark related death in 2018 forced many people to re-evaluate how they view sharks. Not only did people express both positive and negative perceptions of the animals but they also discussed how the attack caused them to change their behavior in and around the ocean. Residents also acknowledged that the sharks were not the only problem living in the ocean. They often blame seals for the shark attacks, while also claiming they are a threat to the fishing industry. -

August 2018 Texas Master Gardener Newsletter President's Message

August 2018 Texas Master Gardener Newsletter President's Message 2019 TMGA Conference Happy August! I heard last night on the news that my neighborhood near Houston has had temperatures above 95 degrees for 24 days straight! Many counties in our state are experiencing significant drought once again. While I was able to go to Canada for a reprieve from the heat, our gardens have not Victoria Master Gardeners are excited about the upcoming 2019 been as fortunate. As trained Master Gardeners, however, we are cognizant of conference. At the Directors Meeting, Victoria MG representatives providing proper plant selection, soil preparation, mulching, water conservation, etc. reported that the City of Victoria is eager to have Master Gardeners next to give our gardens the best possible chance of surviving. If we follow these proven April. In fact, they think this may be the biggest single group of visitors principles, the likelihood is good that our landscapes will make it through these tough that Victoria has ever experienced! Several great speakers and tours are times. As far as how the heat affects us as humans, well, that’s something different already being finalized. The website for the conference is “up,” but altogether! registration and details are planned to be ready on the website around September 1. Bookmark and visit the website frequently to watch for Stay cool and remember that everything changes in time! Autumn comes each year more details and registration. without fail! April 25-27 (Leadership Seminar, April 24) Nicky Maddams Pyramid Island Lake “Victoria – Nature’s Gateway” 2018 TMGA President Jasper National Park, Alberta, Canada Victoria Community Center, 2905 E. -

Elements and Principles of Landscape Design the Visual Appeal of the Landscape

Landscape Design: Elements and Principles Author: Gail Hansen, PhD Environmental Horticulture Department University of Florida IFAS Extension Elements and Principles of Landscape Design The Visual Appeal of the Landscape Outside The Not So Big House 2006 Kit of Parts (with instructions) From Concept to Form in Landscape Design, 1993, Reid, pg 103 From Concept to Form in Landscape Design,1993, Reid, pg 104 Elements - the separate “parts” Principles – the instructions or that interact and work with each guidelines for putting together the other to create a cohesive design parts (elements) to create the design Elements of Design • Line - the outline that creates all forms and patterns in the landscape • Form - the silhouette or shape of a plant or other features in the landscape • Texture - how course or fine a plant or surface feels or looks • Color - design element that adds interest and variety • Visual Weight – the emphasis or force of an individual feature in relation to other features in composition Line • Lines define form and creates patterns. They direct eye movement, and control physical movement. They are real or perceived Straight lines are structural and forceful, curved lines are relaxed and natural, implying movement Lines are found in: • Plant bedlines • Hardscape lines • Plant outlines From Concept to Form in Landscape Design, 1993, Reid, pg 97 Plant Bedlines - connect plant material, house and hardscape. Defines spaces. Garden, Deck and Landscape, spring 1993, pg 60 Bedlines delineate the perimeter of a Landscaping, Better -

American Society of Landscape Architects Medal of Excellence Nominations C/O Carolyn Mitchell 636 Eye Street, NW Washington, DC 20001-3736

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF American Society of Landscape Architects LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS Medal of Excellence Nominations NEW YORK 205 E 42nd St, 14th floor c/o Carolyn Mitchell New York, NY 10017 636 Eye Street, NW 212.269.2984 Washington, DC 20001-3736 www.aslany.org Re: Nomination of Central Park Conservancy for Landscape Architects Medal of Excellence Dear Colleagues: I am thrilled to write this nomination of the Central Park Conservancy for the Landscape Architects Medal of Excellence. The Central Park Conservancy (CPC) is a leader in park management dedicated to the preserving the legacy of urban parks and laying the foundations for future generations to benefit from these public landscapes. Central Park is a masterpiece of landscape architecture created to provide a scenic retreat from urban life for the enjoyment of all. Located in the heart of Manhattan, Central Park is the nation’s first major urban public space, attracting millions of visitors, both local and tourists alike. Covering 843 acres of land, this magnificent park was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1963 and as a New York City Scenic Landmark in 1974. As the organization entrusted with the responsibility of caring for New York’s most important public space, the Central Park Conservancy is founded on the belief that citizen leadership and private philanthropy are key to ensuring that the Park and its essential purpose endure. Conceived during the mid-19th century as a recreational space for residents who were overworked and living in cramped quarters, Central Park is just as revered today as a peaceful retreat from the day-to-day stresses of urban life — a place where millions of New Yorkers and visitors from around the world come to experience the scenic beauty of one of America’s greatest works of art. -

Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design

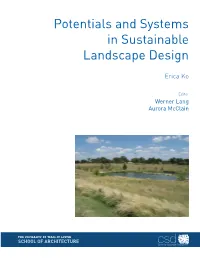

Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design Erica Ko Editor Werner Lang Aurora McClain csd Center for Sustainable Development II-Strategies Site 2 2.2 Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design Erica Ko Based on a presentation by Ilse Frank Figure 1: Five-acre retention pond and native prairie grasses filter and slowly release storm water run-off from adjacent residential development at Mueller Austin, serving an ecological function as well as an aesthetic amenity. Sustainable Landscape Design quickly as possible using heavy urban infra- structure. Today, we are more likely to take Landscape architecture will play an important advantage of the potential for reusing water role in structuring the cities of tomorrow by onsite for irrigation and gray water systems, for allowing landscape strategies to speak more providing habitat, and for slowing storm water closely to shifting cultural paradigms. A de- flows and allowing infiltration to groundwater signed landscape has the ability to illuminate systems—all of which can inspire new forms the interactions between a culture’s view of for integrating water into the built environ- its societal structure and its natural systems. ment. Water can be utilized in remarkable Landscape architecture employs many of the variety of ways–-as a physical boundary, an same design techniques as architecture, but is ecological habitat, or even a waste filtration unique in how it deals with time as a function system. A large-scale example of an outmoded of design (Figure 2), its materials palette, and approach is the Rio Bravo/Rio Grande, which how form is made. -

Lehigh County Potato Region

Agricultural Resources of Pennsylvania, c 1700-1960 Lehigh County Potatoes Historic Agricultural Region, 1850-1960 2 Lehigh County Potatoes Historic Agricultural Region, 1850-1960 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 Location ......................................................................................................................... 8 Climate, Soils, and Topography .................................................................................... 9 Historical Farming Systems ........................................................................................... 9 1850-1910: Potatoes as One Component of a Diversified Farming System ................................................................................................. 9 1910-1960: Potatoes as a Primary Cash Crop with Diversified Complements .....................................................................................................30 Property Types and Registration Requirements – Criterion A, Pennsylvania......................................................................................... 78 Property Types and Registration Requirements – Criterion A, Lehigh County Potatoes Historic Agricultural Region, 1850-1960 ............................................................................... 82 Property Types and Registration Requirements – Criterion B, C, and D ............................................................................................... -

LSU Hilltop Arboretum Master Plan

LSU Hilltop Arboretum Master Plan August 2017 HISTORY AND OVERVIEW Hilltop Arboretum was entrusted to Louisiana State University in 1981 as a gift from its former resident and creator, Emory Smith. Emory and his wife Annette lived a humble lifestyle at the Highland Road property for over 50 years. The land functioned as a working vegetable and livestock farm, however there is more to the story. Emory had a deep love for the plants of Louisiana and spent countless hours collecting native specimens along the Gulf Coast to grow and display on his property. He opened the farm to the public - including classes of students in landscape architecture - and provided walking trails throughout the planted ravines so as to share the enjoyment of his extensive collection. Today, under the careful guidance of the LSU Robert Reich School of Landscape Architecture and the Friends of Hilltop Arboretum, Hilltop continues to carry on Emory’s legacy. Hilltop site circa 1941 MISSION The mission of the LSU Hilltop Arboretum is to provide a sanctuary where students and visitors can learn about natural systems, plants, and landscape design. SHARED VISION The LSU Hilltop Arboretum will be a nationally- recognized center for the study of plants and landscape design. Hilltop will build upon donor Emory Smith’s love for native Louisiana plants and sanctuary. Stewardship of Hilltop is shared by the LSU Robert Reich School of Landscape Architecture and the Friends of Hilltop. Hilltop is an integral part of the School which uses the arboretum in its research, teaching, and service activities. Friends of Hilltop will provide education programs to engage the broader community, operational support, and fundraising activities. -

Garden Design and Plant Selection

Garden Design and Plant Selection Now that you have selected your project goals and learned about your site’s light and soil conditions, you can start designing your Stormwater Action Project. A design shows the shape of your conservation garden and the placement of plants, trees, and shrubs. It usually is done on a grid, so that you can plan the garden dimensions and pick the right number of plants. As you draw the plants on the design, you will leave the appropriate amount of space between them. (Different plants need different amounts of growing space.) The design process usually takes a number of draft drawings, as you try out different garden shapes and different plants. Here are some design guidelines that might help: Have fun and trust your creative spirit. A tree or shrubs can act as focal points or as backdrops, depending upon the site. Have a mix of short, medium, and tall plants. Usually, short ones go in the front and tall ones in The centers of perennial plants are usually 12 to back. 18 inches apart. Trees and shrubs are placed many feet apart. Their spacing will need to be Select plants that bloom in different months, so you will have color throughout the season. researched. Large groups of flowers are more dramatic than Clearly defined borders of a garden can bring unity many small groups. A mix of large groupings and to an informal shape. smaller ones draw a viewer’s attention. Repetition of flowers or colors throughout a Odd numbers of plants are esthetically pleasing.