Chapter 1 the Development of Landscape Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Sustainable Regional Design Strategies Successful

sustainability Article Making Sustainable Regional Design Strategies Successful Anastasia Nikologianni 1,*, Kathryn Moore 1 and Peter J. Larkham 2 1 School of Architecture and Design, Birmingham City University, City Centre Campus, B4 7BD Birmingham, UK; [email protected] 2 School of Engineering and the Built Environment, Birmingham City University, B4 7BD Birmingham, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-(0)-7557386272 Received: 18 December 2018; Accepted: 8 February 2019; Published: 16 February 2019 Abstract: This paper identifies innovative methods of strategic spatial design to demonstrate the sustainable outcomes that can be achieved by adopting landscape practices to future-proof our cities and regions. A range of strategic landscape-led models and methodologies are investigated to reveal the structure, administrative processes and key elements that have been adopted in order to facilitate the integration of climate change environmental design and landscape quality. We have found that a strong established framework that demonstrates innovative project management and early integration of environmental ideas is critical in order to be able to deliver landscape schemes that appropriately identify and address current climatic and social challenges. Furthermore, to make a real difference in the way that professional practice and politics deal with landscape infrastructure, the project framework and key concepts related to landscape design and planning, such as low carbon design and spatial quality, need to be clearly supported by legislation and policy at all levels. Together with close attention to the importance of design, this approach is more likely to ensure effective implementation and smooth communication during the development of a landscape scheme, leading to higher levels of sustainability and resilience in the future. -

Environmental Justice + Landscape Architecture: a Student's Guide

ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE a students’ guide This guide was written by three masters of landscape architecture students who wanted to learn more about how landscape architecture can promote social justice and equity through design. In 2016 we became the student representatives for the ASLA's Environmental Justice Professional Practice Network so we could better connect the important work of professionals, academics, and activists working towards environmental justice with students. This guide is a response to our own desires to educate ourselves about environmental justice and share what we learned. It is a starting-off place for students - a compendium of resources, conversations, case studies, and activities students can work though and apply to their studio projects. It is a continuously evolving project and we invite you to get in touch to give us feedback, ask questions, and give us ideas for this guide. We are: Kari Spiegelhalter Cornell University Masters of Landscape Architecture 2018 [email protected] Tess Ruswick Cornell University Masters of Landscape Architecture 2018 [email protected] Patricia Noto Rhode Island School of Design Masters of Landscape Architecture 2018 [email protected] We have a long list of people to thank who helped us seek resources, gave advice, feedback and support as this guide was written. We'd like to give a huge thank you to: The ASLA Environmental Justice Professional Practice Network for helping us get this project off the ground, especially Erin McDonald, Matt Romero, Julie Stevens, -

School of Design and Community Development 1

School of Design and Community Development 1 School of Design and Community Development Nature of the School The majors in the School of Design and Community Development focus on improving the quality of life of individuals and groups by designing interactions, educational programs, and services between people and their environments to better address the needs and desires of communities and their residents. We imagine, educate, evaluate, plan, and produce experiences, products, settings and services that have the potential to transform lives. Given the range of our programs and the portability of skills taught in them, outcomes for students vary. Our graduates find employment in professional design settings and interdisciplinary firms; in communities as teachers, as extension agents, and community development specialists. Graduates create careers as entrepreneurs and in traditional design, business and retail settings. And others find placement in a wide spectrum of innovative organizations that use design and design thinking as a way to fully understand and engage with their clients and markets. Study abroad is strongly encouraged in all of our programs, and is required in Interior Design. Accreditation The agricultural and extension education program is accredited by the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE). The fashion, dress and merchandising program is an affiliate member of the Textile and Apparel Programs Accreditation Commission (TAPAC). The interior design program is accredited by the National Association of Schools of Art and Design (NASAD). The landscape architecture program is accredited by the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA). FACULTY DIRECTOR • Peter Butler - M.L.A. (Iowa State) Landscape Architecture - Cultural landscape planning and interpretation, Community design processes, Design pedagogy PROFESSORS • Cindy Beacham - Ph.D. -

SUSTAINABLE LANDSCAPE DESIGN at Macomb Community College

SUSTAINABLE LANDSCAPE DESIGN at Macomb Community College BASIC LANDSCAPE DESIGN CERTIFICATES IN LANDSCAPE DESIGN CERTIFICATE—(6 Classes) • Basic Landscape Design Landscape Design Graphics • Advanced Landscape Design Learn the principles of drafting and plan reading. Different design • Environmental Horticulture styles will be explored and practiced. Learn the required skills and receive state-of-the-art information Landscape Design Principles necessary to develop a solid foundation in the original “Green Explore how design principles and elements of art are applied to Industry.” The Sustainable Landscape Design Program encourages create a functional, sustainable, and aesthetically pleasing outdoor professional standards, a strong work ethic, and sound management extension of indoor living. practices. Your classes will be taught by Rick Lazzell, a Certified Natural The Design & Sales Process Shoreline Professional with over 30 years of experience. Review marketing your services, initial client contact, client interview, design presentation, and portfolio development. If applicable, bring ENVIRONMENTAL HORTICULTURE your site evaluation rendering to the first session. CERTIFICATE—(7 Classes) Residential Landscape Planting Design Learn plant material composition and design characteristics. Basic Horticulture/How Plants Grow Review sustainable landscape design criteria, including selection, Discover how a plant grows, its relationship with the soil, its climate, cultural suitability, availability, costs, and maintenance. water and nutrient -

Ideas and Tradition Behind Chinese and Western Landscape Design

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Landscape Planning, Horticulture and Agricultural Science Department of Landscape Architecture Ideas and Tradition behind Chinese and Western Landscape Design - similarities and differences Junying Pang Degree project in landscape planning, 30 hp Masterprogramme Urban Landscape Dynamics Independent project at the LTJ Faculty, SLU Alnarp 2012 1 Idéer och tradition bakom kinesisk och västerländsk landskapsdesign Junying Pang Supervisor: Kenneth Olwig, SLU, Department of Landscape Architecture , , Assistant Supervisor: Anna Jakobsson, SLU, Department of Landscape Architecture , , Examiner: Eva Gustavsson, SLU, Department of Landscape Architecture , , Credits: 30 hp Level: A2E Course title: Degree Project in the Masterprogramme Urban Landscape Dynamics Course code: EX0377 Programme/education: Masterprogramme Urban Landscape Dynamics Subject: Landscape planning Place of publication: Alnarp Year of publication: January 2012 Picture cover: http://photo.zhulong.com/proj/detail4350.htm Series name: Independent project at the LTJ Faculty, SLU Online publication: http://stud.epsilon.slu.se Key Words: Ideas, Tradition, Chinese landscape Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Landscape Planning, Horticulture and Agricultural Science Department of Landscape Architecture 2 Forward This degree project was written by the student from the Urban Landscape Dynamics (ULD) Programme at Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU). This programme is a two years master programme, and it relates to planning and designing of the urban landscape. The level and depth of this degree project is Master E, and the credit is 30 Ects. Supervisor of this degree project has been Kenneth Olwig, professor at the Department of Landscape architecture; assistant supervisor has been Anna Jakobsson, teacher and research assistant at the Department of Landscape architecture; master’s thesis coordinator has been Eva Gustavsson, senior lecturer at the Department of Landscape architecture. -

Growth by Design

Report - June 2011 Growth by Design This report details the powerful economic impact of New York's architecture and design sectors. It shows that New York has far more designers than any other U.S. city, but concludes that far more could be done to harness the sector's growth potential. by David Giles This is an excerpt. Click here to read the full report (PDF). Facing the possibility that New York City’s financial services sector will never again reach the job levels of 2007, city economic development officials are moving aggressively to identify ways to grow and diversify the economy. Policymakers have embraced sectors from digital media and biotechnology to clean tech. But thus far little attention has been paid to a part of the economy that has experienced phenomenal growth over the past decade and for which New York holds a significant competitive advantage: design. Though fewer and fewer products are actually made in high-cost cities like New York, the Big Apple has cemented its status as one of the few global hubs for where things are designed. In 2009, the New York metro-region was home to 40,470 designers, which is far and away the largest pool of design talent in the country and among two or three of the largest in the world. In addition, no other American city has strengths in so many design fields—from architecture to fashion design, graphic design, interior design, furniture design and industrial design. Image not readable or empty /images/uploads/Growth_by_Design_-_Info.png The design sector has also been expanding at a rapid clip. -

NJASLA 2014 Awards Program

The New Jersey Chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects is pleased to present the 2014 Professional Awards. The awards program is intended to help broaden the boundaries of our profession; increase public awareness of the role of landscape architects; raise the standards of our discipline; and bring recognition to organizations and individuals who demonstrate superior skill in the practice and study of landscape architecture. A jury of distinguished landscape architects reviewed twenty-one submissions and selected win- ners in fi ve categories. We invite you to view the winning projects throughout the conference on our continuously-running video presentation located on the conference fl oor. The winners will also be featured in upcoming newsletters, our website and other events which promote our profes- sion throughout the state during the course of the year. Thank you for attending this year’s presentation. We hope you enjoy this year’s ceremonies and strongly encourage you to consider submitting your work for next year’s program. Eric Mattes Denise Mattes HONORINGour past 2014 AWARDS JURY EMBRACING Dr. Wolfram Hoefer, Rutgers University our future Wolfram is an Associate Professor at the Department of Landscape Architecture at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey and serves as Undergraduate Program Director for the department. He also serves as Co-Director of the #NJASLA50 Rutgers Center for Urban Environmental Sustainability. In 1992 he earned a Diploma in Landscape Architecture from the Technische Universität Berlin and received a doctoral degree from Technische Universtät München in 2000. He is a licensed Landscape Architect in the state of Bavaria, Germany. -

Anthrozoology and Sharks, Looking at How Human-Shark Interactions Have Shaped Human Life Over Time

Anthrozoology and Public Perception: Humans and Great White Sharks (Carchardon carcharias) on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA Jessica O’Toole A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Marine Affairs University of Washington 2020 Committee: Marc L. Miller, Chair Vincent F. Gallucci Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Marine and Environmental Affairs © Copywrite 2020 Jessica O’Toole 2 University of Washington Abstract Anthrozoology and Public Perception: Humans and Great White Sharks (Carchardon carcharias) on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA Jessica O’Toole Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Marc L. Miller School of Marine and Environmental Affairs Anthrozoology is a relatively new field of study in the world of academia. This discipline, which includes researchers ranging from social studies to natural sciences, examines human-animal interactions. Understanding what affect these interactions have on a person’s perception of a species could be used to create better conservation strategies and policies. This thesis uses a mixed qualitative methodology to examine the public perception of great white sharks on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. While the area has a history of shark interactions, a shark related death in 2018 forced many people to re-evaluate how they view sharks. Not only did people express both positive and negative perceptions of the animals but they also discussed how the attack caused them to change their behavior in and around the ocean. Residents also acknowledged that the sharks were not the only problem living in the ocean. They often blame seals for the shark attacks, while also claiming they are a threat to the fishing industry. -

Home Landscape Design

Home Landscape Design well-designed and functional home landscape can add to Ayour family’s joy and increase the value of your property. Modern landscapes are meant to be beautiful and useful. A well- Figure 1. Front landscape. Drawing by Richard Martin III. planned landscape provides your family with recreation, privacy, and pleasure. Conscientious homeowners know that the landscape should also have a positive environmental impact. Figures 1 and 2 depict the front and back yards of a Southern home. Throughout this publica - tion, each step of landscape design is illustrated using this sample landscape. If you want to jump ahead, the completed landscape plan is Figure 33 . This publication is designed for avid gardeners and gives simple, basic approaches to creating a visu - ally appealing, practical home landscape. If you are computer savvy, you may find it helpful to use a landscape design software program to help you through the process. By following the step-by-step process of landscape design, you can beautify your property, add to its value and bring it to life with your own personality and style. The best landscapes reflect the uniqueness of the family and the region. Whether you want to do it yourself or leave it to a professional, this publica - tion will help you understand the process that is involved in designing a landscape. Understanding the process will help you to ask the right questions when and if you consult a professional. Figure 2. Back landscape. Drawing by Richard Martin III. Professional Help Value of Landscaping The idea of designing a home landscape can intimidate An ideal home landscape design should have value in four even serious gardeners. -

American Society of Landscape Architects Medal of Excellence Nominations C/O Carolyn Mitchell 636 Eye Street, NW Washington, DC 20001-3736

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF American Society of Landscape Architects LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS Medal of Excellence Nominations NEW YORK 205 E 42nd St, 14th floor c/o Carolyn Mitchell New York, NY 10017 636 Eye Street, NW 212.269.2984 Washington, DC 20001-3736 www.aslany.org Re: Nomination of Central Park Conservancy for Landscape Architects Medal of Excellence Dear Colleagues: I am thrilled to write this nomination of the Central Park Conservancy for the Landscape Architects Medal of Excellence. The Central Park Conservancy (CPC) is a leader in park management dedicated to the preserving the legacy of urban parks and laying the foundations for future generations to benefit from these public landscapes. Central Park is a masterpiece of landscape architecture created to provide a scenic retreat from urban life for the enjoyment of all. Located in the heart of Manhattan, Central Park is the nation’s first major urban public space, attracting millions of visitors, both local and tourists alike. Covering 843 acres of land, this magnificent park was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1963 and as a New York City Scenic Landmark in 1974. As the organization entrusted with the responsibility of caring for New York’s most important public space, the Central Park Conservancy is founded on the belief that citizen leadership and private philanthropy are key to ensuring that the Park and its essential purpose endure. Conceived during the mid-19th century as a recreational space for residents who were overworked and living in cramped quarters, Central Park is just as revered today as a peaceful retreat from the day-to-day stresses of urban life — a place where millions of New Yorkers and visitors from around the world come to experience the scenic beauty of one of America’s greatest works of art. -

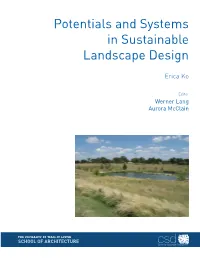

Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design

Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design Erica Ko Editor Werner Lang Aurora McClain csd Center for Sustainable Development II-Strategies Site 2 2.2 Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design Erica Ko Based on a presentation by Ilse Frank Figure 1: Five-acre retention pond and native prairie grasses filter and slowly release storm water run-off from adjacent residential development at Mueller Austin, serving an ecological function as well as an aesthetic amenity. Sustainable Landscape Design quickly as possible using heavy urban infra- structure. Today, we are more likely to take Landscape architecture will play an important advantage of the potential for reusing water role in structuring the cities of tomorrow by onsite for irrigation and gray water systems, for allowing landscape strategies to speak more providing habitat, and for slowing storm water closely to shifting cultural paradigms. A de- flows and allowing infiltration to groundwater signed landscape has the ability to illuminate systems—all of which can inspire new forms the interactions between a culture’s view of for integrating water into the built environ- its societal structure and its natural systems. ment. Water can be utilized in remarkable Landscape architecture employs many of the variety of ways–-as a physical boundary, an same design techniques as architecture, but is ecological habitat, or even a waste filtration unique in how it deals with time as a function system. A large-scale example of an outmoded of design (Figure 2), its materials palette, and approach is the Rio Bravo/Rio Grande, which how form is made. -

LSU Hilltop Arboretum Master Plan

LSU Hilltop Arboretum Master Plan August 2017 HISTORY AND OVERVIEW Hilltop Arboretum was entrusted to Louisiana State University in 1981 as a gift from its former resident and creator, Emory Smith. Emory and his wife Annette lived a humble lifestyle at the Highland Road property for over 50 years. The land functioned as a working vegetable and livestock farm, however there is more to the story. Emory had a deep love for the plants of Louisiana and spent countless hours collecting native specimens along the Gulf Coast to grow and display on his property. He opened the farm to the public - including classes of students in landscape architecture - and provided walking trails throughout the planted ravines so as to share the enjoyment of his extensive collection. Today, under the careful guidance of the LSU Robert Reich School of Landscape Architecture and the Friends of Hilltop Arboretum, Hilltop continues to carry on Emory’s legacy. Hilltop site circa 1941 MISSION The mission of the LSU Hilltop Arboretum is to provide a sanctuary where students and visitors can learn about natural systems, plants, and landscape design. SHARED VISION The LSU Hilltop Arboretum will be a nationally- recognized center for the study of plants and landscape design. Hilltop will build upon donor Emory Smith’s love for native Louisiana plants and sanctuary. Stewardship of Hilltop is shared by the LSU Robert Reich School of Landscape Architecture and the Friends of Hilltop. Hilltop is an integral part of the School which uses the arboretum in its research, teaching, and service activities. Friends of Hilltop will provide education programs to engage the broader community, operational support, and fundraising activities.