Palaeolithic British Isles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bus and Rail Guide

FREQUENCY GUIDE FREQUENCY (MINUTES) Chatham Town Centre Gillingham Town Centre Monday – Friday Saturday Sunday Operator where to board your bus where to board your bus Service Route Daytime Evening Daytime Evening Daytime Evening 1 M Chatham - Chatham Maritime - Dockside Outlet Centre - Universities at Medway Campus 20 minutes - 20 minutes - hourly - AR Destination Service Number Bus Stop (- Gillingham ASDA) - Liberty Quays - The Strand (- Riverside Country Park (Suns)) Fort Amherst d t . i a e Hempstead Valley 116 E J T o e t Coouncil Offices r . R t e Trinity Road S d R e 2 S M Chatham - Chatham Maritime - Dockside Outlet Centre 20 minutes 20 minutes 20 minutes 20 minutes 20 minutes 20 minutes AR m Medway r u ll t Liberty Quays 176 177 (Eves/Sun) D H D o PUBLIC x rt Y i S ha Park o O K M A CAR F n t 6*-11* Grain - Lower Stoke - Allhallows - High Halstow - Hoo - Hundred of Hoo Academy school - - - - - AR 16 e C C e PPARKARK d ro Lower Halstow 326 327 E J e s W W r s Chathamtham Library K i r T Bus and rail guide A t A E S 15 D T S R C tr E E e t 100 M St Mary’s Island - Chatham Maritime - Chatham Rail Station (see also 1/2 and 151) hourly - hourly - - - AR and Community Hub E e t O 19 R E Lower Rainham 131* A J T F r R e A R F e T e E . r D M T n S t Crown St. -

Clarendon Team News 20-04-2014

TEAM CHOIR for Holy Week and Easter Could all Team Choir members please email [email protected] so that we can build Clarendon TEAM news up a distribution list for the Team Choir. We can then let you know about any singing opportunities Clarendon Team Notices for Sunday 20th April 2014 that may come up in the Team. Thank you! Winterslow Christian Aid Lunches Services in Team Churches over the next two weeks Lunches at Truffles coffee shop on Thursday 1st May from 12 - 2pm in aid of Christian Aid. Readings: 20th April - Jeremiah 31.1-6 Acts 10.34-43 John 20.1-18 or Matthew 28.1-10 Whiteparish Music Festival (in aid of Church running costs) 27th April - Exodus 14.10-31; 15.20-21 Acts 2.14a,22-32 John 20.19-31 Tickets now on sale from Whiteparish Village Shop or The Music Room, Salisbury. Saturday 3rd May - “Jazz in the Church”, Wednesday 7th May - “Music for a Summer’s Night”, CHURCH 20th April - 27th April - Sunday 11th May - “Debussy to Disney”. To be held in All Saints Church, Whiteparish. Easter Day Second Sunday of Easter Please see the link for more info: www.clarendonteam.org/WHITEPARISHMUSICFESTIVAL2014.pdf ALDERBURY 9.30am All Age Easter Eucharist 9.30am Healing Eucharist 6pm Evening Prayer (Alt Utd Svc) Open Garden at Kings Farm - Proceeds to C of E, Methodist Church and Parkinsons Society WHADDON Sunday 4th May at Kings Farm, Livery Rd, West Winterslow from 2 - 4pm. There will be bring and at St Mary’s Hall with RC Preacher buy, raffles (Carol Hampton), Tombola (Janet Fry), books, bric-a-brac, tea and cakes. -

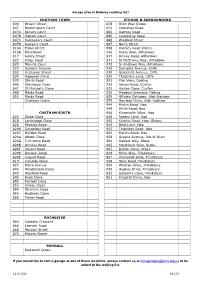

Garage Sites in Medway (Waiting List)

Garage sites in Medway (waiting list) CHATHAM TOWN STROOD & SURROUNDING 804 Bryant Street 878 Bligh Way Shops 807 Blockmakers Court 879 Carnation Road 807A Joiners Court 882 Darnley Road 807B Oakum Court 885 Leybourne Road 807C Sailmakers Court 888 Windmill Street 807D Sawyers Court 897 North Street 816A Eldon Street 898 Darnley Road Stores 816B Hardstown 916 Avery Way, Allhallows 817 Henry Street 917 Binney Road, Allhallows 823 Kings Road 971 St Matthews Way, Allhallows 829 Melville Court 972 St Andrews Way, Allhallows 830 Symons Avenue 918 Swingate Avenue, Cliffe 832 Ordnance Street 919 Quickrells Avenue, Cliffe 834 Hopewell Drive 920 Thatchers Lane, Cliffe 839 Sturla Road 921 Pips View, Cooling 846 Glenwood Close 922 James Road, Cuxton 847 St Michael’s Close 923 Hayley Close, Cuxton 848 Maida Road 935 Meadow Crescent, Halling 850 Maida Road 939 Hillview Cottages, High Halstow Chatham Grove 979 Harrison Drive, High Halstow 944 Miskin Road, Hoo 945 Wylie Road, Hoo CHATHAM SOUTH 946 Kingsnorth Villas, Hoo 820 Slade Close 948 Ropers Lane, Hoo 818 Lordswood Close 950 Knights Road, Hoo (Shops) 826 Phoenix Road 943 Bells Lane, Hoo 826H Sandpiper Road 955 Trubridge Road, Hoo 826C Bulldog Road 956 Marley Road, Hoo 826A Albion Close 958 Grayne Avenue, Isle of Grain 826G Turnstone Road 981 Mallard Way, Stoke 826B Achilles Road 965 Marshland View, Stoke 826F Valiant Road 967 Button Drive, Stoke 826D Renown Road 926 Miller Way, Frindsbury 826E Cygnet Road 927 Wainscott Walk, Frindsbury 819 Ironside Close 928 Holly Road, Frindsbury 827 Malta Avenue 929 Winston Drive, Frindsbury 842 Walderslade Road 930 Hughes Drive, Frindsbury 843 Wayfield Road 933 Gardenia Close, Frindsbury 849 Ryde Close 951 Kingshill Drive, Hoo 852 Penfold Close 853 Vulcan Close 854 Shanklin Close 855 Anglesey Close 856 Fisher Road ROCHESTER 860 Cordelia Crescent 866 Leander Road 868 Mordon Street 870 Princes Street TWYDALL Eastcourt Green If you would like to rent a garage at one of these locations, please contact us at [email protected] to be added to the waiting list. -

Karl Jordan: a Life in Systematics

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Kristin Renee Johnson for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of SciencePresented on July 21, 2003. Title: Karl Jordan: A Life in Systematics Abstract approved: Paul Lawrence Farber Karl Jordan (1861-1959) was an extraordinarily productive entomologist who influenced the development of systematics, entomology, and naturalists' theoretical framework as well as their practice. He has been a figure in existing accounts of the naturalist tradition between 1890 and 1940 that have defended the relative contribution of naturalists to the modem evolutionary synthesis. These accounts, while useful, have primarily examined the natural history of the period in view of how it led to developments in the 193 Os and 40s, removing pre-Synthesis naturalists like Jordan from their research programs, institutional contexts, and disciplinary homes, for the sake of synthesis narratives. This dissertation redresses this picture by examining a naturalist, who, although often cited as important in the synthesis, is more accurately viewed as a man working on the problems of an earlier period. This study examines the specific problems that concerned Jordan, as well as the dynamic institutional, international, theoretical and methodological context of entomology and natural history during his lifetime. It focuses upon how the context in which natural history has been done changed greatly during Jordan's life time, and discusses the role of these changes in both placing naturalists on the defensive among an array of new disciplines and attitudes in science, and providing them with new tools and justifications for doing natural history. One of the primary intents of this study is to demonstrate the many different motives and conditions through which naturalists came to and worked in natural history. -

2013 CAG Library Index

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

C H a P T E R VII Comparison of Stone Age Cultures the Cultural

158 CHAPTER VII Comparison of Stone Age Cultures The cultural horizons ami pleistocene sequences of the Upper Son Valley are compared with the other regions to know their positions in the development of Stone Age Cultures* However, ft must not be forgotten that the industries of various regions were more or less in fluenced by the local factors: the environment, geology f topography, vegetation, climate and animals; hence some vsriitions are bound to occur in them* The comparison is first made with industries within India and then with those outside India. i) Within India • Punjab Potwar The Potwar region, which lies between the Indus and Jhebm, including the Salt Range, was examined by Oe Terra and Pater son. The latter has recently published a revised 2 stuiy of the cultural horizons. 1. De Terra, H., and Paterson, T.T., 1939, Studies on the Ice Age in India and Associated Human Culture, pp.252-312 2. Paterson, T.T., and Drummond, H.J.H., 1962, Soan,the Palaeolithic of Pakistan. These scholars had successfully located six terraces (Including TD) in the Sohan Valley: "nowhere else in the Potwar is the leistocene history so well recorded as along the So&n Hiver and its tributaries.w The terraces TD and TI placed in the Second Glacial and Second Inter- glacial, respectively fall in the Middle Pleistocene, terraces ? and 3 originated in Third Glacial and Inter- glaual period. Th succeeding terrace viz., T4 has bean connected with the Fourth Glacial period. The last terrace - T5 - belongs to Post-glacLal and Holacene time. The oldest artifacts are located in the Boulder Con glomerate and are placed in the earliest Middle Pleisto cene or Lower Pleistocene. -

Wilsomdor, Chapel Hill, West Grimstead, Price: £585,000 Salisbury, Wiltshire, Sp5 3Sg

WILSOMDOR, CHAPEL HILL, WEST GRIMSTEAD, PRICE: £585,000 SALISBURY, WILTSHIRE, SP5 3SG A BEAUTIFULLY PRESENTED DETACHED HOUSE WITH EXCELLENT ANNEXE AND SOUTH FACING GARDEN ON THE EAST SIDE OF SALISBURY DIRECTIONS: From Salisbury proceed out south east on the A36 Southampton Road and continue along the Alderbury bypass until you see a turning on the left signposted The Grimsteads. Turn off here, branch left at the T-junction and continue along here until you come to another junction and then turn left into Crockford Lane. Proceed along here until you come to the railway bridge, turn right into Chapel Hill and the property will be found immediately on the right hand side. DESCRIPTION: This is a superb detached house with the benefit of a one bedroom annexe, located in a very popular village on the eastern side of Salisbury. The original house dates back to the early 1970s, was extended in 2016 and has been completely refurbished in recent years. Construction is of brick elevations under a tile roof and the house has the benefit of LPG central heating, part of which is under floor, as well as full double glazing. To the side of the house the former double garage has been converted into an excellent one bedroom annexe with a kitchen/breakfast room, living room, dressing room, shower room and double bedroom on the first floor. There is also parking for four cars to the front of the annexe and an attractive south facing garden with patio and lawn and views over open fields. LOCATION: The property is located in West Grimstead some five miles to the east of the city of Salisbury. -

172 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

172 bus time schedule & line map 172 Chatham - Lodge Hill View In Website Mode The 172 bus line (Chatham - Lodge Hill) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chatham: 9:27 AM - 12:27 PM (2) Lodge Hill: 10:20 AM - 4:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 172 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 172 bus arriving. Direction: Chatham 172 bus Time Schedule 34 stops Chatham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 9:27 AM - 12:27 PM Lodge Hill Lane, Lodge Hill Tuesday 9:27 AM - 12:27 PM Swinton Avenue, Lodge Hill Wednesday 9:27 AM - 12:27 PM Kirby Road, Lodge Hill Thursday 9:27 AM - 12:27 PM Copse Farm, Hoo St. Werburgh Civil Parish Friday 9:27 AM - 12:27 PM Primary School, Chattenden Tudor Grove, Hoo St. Werburgh Civil Parish Saturday 9:27 AM - 2:07 PM Liberty Park, Wainscott 1A Wainscott Road, Frindsbury Extra Civil Parish Higham Road, Wainscott 172 bus Info 4 Wainscott Road, Frindsbury Extra Civil Parish Direction: Chatham Stops: 34 Greenƒelds Close, Wainscott Trip Duration: 28 min Holywood Lane, Frindsbury Extra Civil Parish Line Summary: Lodge Hill Lane, Lodge Hill, Swinton Avenue, Lodge Hill, Kirby Road, Lodge Hill, Primary Jarrett Avenue, Wainscott School, Chattenden, Liberty Park, Wainscott, Higham 63 Hollywood Lane, Frindsbury Extra Civil Parish Road, Wainscott, Greenƒelds Close, Wainscott, Jarrett Avenue, Wainscott, Hollywood Lane Middle, Hollywood Lane Middle, Wainscott Wainscott, Cooling Road, Frindsbury, Lower 121 Hollywood Lane, Frindsbury Extra Civil Parish -

A CRITICAL EVALUATION of the LOWER-MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD of the CHALK UPLANDS of NORTHWEST EUROPE Lesley

A CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE LOWER-MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD OF THE CHALK UPLANDS OF NORTHWEST EUROPE The Chilterns, Pegsdon, Bedfordshire (photograph L. Blundell) Lesley Blundell UCL Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD September 2019 2 I, Lesley Blundell, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: 3 4 Abstract Our understanding of early human behaviour has always been and continues to be predicated on an archaeological record unevenly distributed in space and time. More than 80% of British Lower-Middle Palaeolithic findspots were discovered during the late 19th/early 20th centuries, the majority from lowland fluvial contexts. Within the British planning process and some academic research, the resultant findspot distributions are taken at face value, with insufficient consideration of possible bias resulting from variables operating on their creation. This leads to areas of landscape outside the river valleys being considered to have only limited archaeological potential. This thesis was conceived as an attempt to analyse the findspot data of the Lower-Middle Palaeolithic record of the Chalk uplands of southeast Britain and northern France within a framework complex enough to allow bias in the formation of findspot distribution patterns and artefact preservation/discovery opportunities to be identified and scrutinised more closely. Taking a dynamic, landscape = record approach, this research explores the potential influence of geomorphology, 19th/early 20th century industrialisation and antiquarian collecting on the creation of the Lower- Middle Palaeolithic record through the opportunities created for artefact preservation and release. -

References Geological Society, London, Memoirs

Geological Society, London, Memoirs References Geological Society, London, Memoirs 2002; v. 25; p. 297-319 doi:10.1144/GSL.MEM.2002.025.01.23 Email alerting click here to receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article service Permission click here to seek permission to re-use all or part of this article request Subscribe click here to subscribe to Geological Society, London, Memoirs or the Lyell Collection Notes Downloaded by on 3 November 2010 © 2002 Geological Society of London References ABBATE, E., BORTOLOTTI, V. & PASSERINI, P. 1970. Olistostromes and olis- ARCHER, J. B, 1980. Patrick Ganly: geologist. Irish Naturalists' Journal, 20, toliths. Sedimentary Geology, 4, 521-557. 142-148. ADAMS, J. 1995. Mines of the Lake District Fells. Dalesman, Skipton (lst ARTER. G. & FAGIN, S. W. 1993. The Fieetwood Dyke and the Tynwald edn, 1988). fault zone, Block 113/27, East Irish Sea Basin. In: PARKER, J. R. (ed.), AGASSIZ, L. 1840. Etudes sur les Glaciers. Jent & Gassmann, Neuch~tel. Petroleum Geology of Northwest Europe: Proceedings of the 4th Con- AGASSIZ, L. 1840-1841. On glaciers, and the evidence of their once having ference held at the Barbican Centre, London 29 March-1 April 1992. existed in Scotland, Ireland and England. Proceedings of the Geo- Geological Society, London, 2, 835--843. logical Society, 3(2), 327-332. ARTHURTON, R. S. & WADGE A. J. 1981. Geology of the Country Around AKHURST, M. C., BARNES, R. P., CHADWICK, R. A., MILLWARD, D., Penrith: Memoir for 1:50 000 Geological Sheet 24. Institute of Geo- NORTON, M. G., MADDOCK, R. -

OBITUARIES Sir Edward Poulton, F.R.S

No. 3870, jANUARY 1, 1944 NATURE 15 the University of Edinburgh, previously held by a tragic death, and his successor, F. Hasenohrl, was Black. To him we owe the discovery of the maximum killed in action on the Italian front in 1915. The density of water. The centenary of John Dalton falls chemists born in 1844 include Prof. J. Emerson on July 27 of this year, but any commemoration Reynolds (died 1920), who occupied for twenty-eight must inevitably be clouded over by the results of years the chair of chemistry in the University of the air raid of December 24, 1940, when the premises Dublin, and Ferdinand Hurter (died 1898), a native of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society of Schaffhausen, Switzerland, who came to England were completely destroyed. From 1817 until 1844 in 1867 and became principal chemist to the United DaJton was president of the Society, and within its Alkali Company. Among astronomers, Prof. W. R. walls he taught, lectured and experimented. The Brooks (died 1921) of the United States was famous Society had an unequalled collection of his apparatus, as a 'comet hunter'. Charles Trepied (died 1907) was but after digging among the ruins the only things for many years director of the Observatory at found were his gold watch, a spark eudiometer and Bouzariah, eleven kilometres from Algiers, while some charred remains of letters and note-books. A Annibale Ricco (died 1919), though he began life as month after Dalton passed away in Manchester, an engineer, for nineteen years directed the observa Francis Baily died in London, after a life devoted to tory of Catania and Etna, his special subject being astronomy and kindred subjects. -

Historiographical Approaches to Past Archaeological Research

Historiographical Approaches to Past Archaeological Research Gisela Eberhardt Fabian Link (eds.) BERLIN STUDIES OF THE ANCIENT WORLD has become increasingly diverse in recent years due to developments in the historiography of the sciences and the human- ities. A move away from hagiography and presentations of scientifi c processes as an inevitable progression has been requested in this context. Historians of archae- olo gy have begun to utilize approved and new histo- rio graphical concepts to trace how archaeological knowledge has been acquired as well as to refl ect on the historical conditions and contexts in which knowledge has been generated. This volume seeks to contribute to this trend. By linking theories and models with case studies from the nineteenth and twentieth century, the authors illuminate implications of communication on archaeological knowledge and scrutinize routines of early archaeological practices. The usefulness of di erent approaches such as narratological concepts or the concepts of habitus is thus considered. berlin studies of 32 the ancient world berlin studies of the ancient world · 32 edited by topoi excellence cluster Historiographical Approaches to Past Archaeological Research edited by Gisela Eberhardt Fabian Link Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. © 2015 Edition Topoi / Exzellenzcluster Topoi der Freien Universität Berlin und der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Typographic concept and cover design: Stephan Fiedler Printed and distributed by PRO BUSINESS digital printing Deutschland GmbH, Berlin ISBN 978-3-9816384-1-7 URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:11-100233492 First published 2015 The text of this publication is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC 3.0 DE.