T H E Wilson Quarter.Ly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faith and Thought

1981 Vol. 108 No. 3 Faith and Thought Journal of the Victoria Institute or Philosophical Society of Great Britain Published by THE VICTORIA INSTITUTE 29 QUEEN STREET, LONDON, EC4R IBH Tel: 01-248-3643 July 1982 ABOUT THIS JOURNAL FAITH AND THOUGHT, the continuation of the JOURNAL OF THE TRANSACTIONS OF THE VICTORIA INSTITUTE OR PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY OF GREAT BRITAIN, has been published regularly since the formation of the Society in 1865. The title was changed in 1958 (Vol. 90). FAITH AND THOUGHT is now published three times a year, price per issue £5.00 (post free) and is available from the Society's Address, 29 Queen Street, London, EC4R 1BH. Back issues are often available. For details of prices apply to the Secretary. FAITH AND THOUGHT is issued free to FELLOWS, MEMBERS AND ASSOCIATES of the Victoria Institute. Applications for membership should be accompanied by a remittance which will be returned in the event of non-election. (Subscriptions are: FELLOWS £10.00; MEMBERS £8.00; AS SOCIATES, full-time students, below the age of 25 years, full-time or retired clergy or other Christian workers on small incomes £5.00; LIBRARY SUBSCRIBERS £10.00. FELLOWS must be Christians and must be nominated by a FELLOW.) Subscriptions which may be paid by covenant are accepted by Inland Revenue Authorities as an allowable expense against income tax for ministers of religion, teachers of RI, etc. For further details, covenant forms, etc, apply to the Society. EDITORIAL ADDRESS 29 Almond Grove, Bar Hill, Cambridge, CB3 8DU. © Copyright by the Victoria Institute and Contributors, 1981 UK ISSN 0014-7028 FAITH 1981 AND Vol. -

Planetarian Index

Planetarian Cumulative Index 1972 – 2008 Vol. 1, #1 through Vol. 37, #3 John Mosley [email protected] The PLANETARIAN (ISSN 0090-3213) is published quarterly by the International Planetarium Society under the auspices of the Publications Committee. ©International Planetarium Society, Inc. From the Compiler I compiled the first edition of this index 25 years ago after a frustrating search to find an article that I knew existed and that I really needed. It was a long search without even annual indices to help. By the time I found it, I had run across a dozen other articles that I’d forgotten about but was glad to see again. It was clear that there are a lot of good articles buried in back issues, but that without some sort of index they’d stay lost. I had recently bought an Apple II computer and was receptive to projects that would let me become more familiar with its word processing program. A cumulative index seemed a reasonable project that would be instructive while not consuming too much time. Hah! I did learn some useful solutions to word-processing problems I hadn’t previously known exist, but it certainly did consume more time than I’d imagined by a factor of a dozen or so. You too have probably reached the point where you’ve invested so much time in a project that it’s psychologically easier to finish it than admit defeat. That’s how the first index came to be, and that’s why I’ve kept it up to date. -

Dictionary.Pdf

THE SEAFARER’S WORD A Maritime Dictionary A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Ranger Hope © 2007- All rights reserved A ● ▬ A: Code flag; Diver below, keep well clear at slow speed. Aa.: Always afloat. Aaaa.: Always accessible - always afloat. A flag + three Code flags; Azimuth or bearing. numerals: Aback: When a wind hits the front of the sails forcing the vessel astern. Abaft: Toward the stern. Abaft of the beam: Bearings over the beam to the stern, the ships after sections. Abandon: To jettison cargo. Abandon ship: To forsake a vessel in favour of the life rafts, life boats. Abate: Diminish, stop. Able bodied seaman: Certificated and experienced seaman, called an AB. Abeam: On the side of the vessel, amidships or at right angles. Aboard: Within or on the vessel. About, go: To manoeuvre to the opposite sailing tack. Above board: Genuine. Able bodied seaman: Advanced deckhand ranked above ordinary seaman. Abreast: Alongside. Side by side Abrid: A plate reinforcing the top of a drilled hole that accepts a pintle. Abrolhos: A violent wind blowing off the South East Brazilian coast between May and August. A.B.S.: American Bureau of Shipping classification society. Able bodied seaman Absorption: The dissipation of energy in the medium through which the energy passes, which is one cause of radio wave attenuation. Abt.: About Abyss: A deep chasm. Abyssal, abysmal: The greatest depth of the ocean Abyssal gap: A narrow break in a sea floor rise or between two abyssal plains. -

SEA8 Techrep Mar Arch.Pdf

SEA8 Technical Report – Marine Archaeological Heritage ______________________________________________________________ Report prepared by: Maritime Archaeology Ltd Room W1/95 National Oceanography Centre Empress Dock Southampton SO14 3ZH © Maritime Archaeology Ltd In conjunction with: Dr Nic Flemming Sheets Heath, Benwell Road Brookwood, Surrey GU23 OEN This document was produced as part of the UK Department of Trade and Industry's offshore energy Strategic Environmental Assessment programme. The SEA programme is funded and managed by the DTI and coordinated on their behalf by Geotek Ltd and Hartley Anderson Ltd. © Crown Copyright, all rights reserved Document Authorisation Name Position Details Signature/ Initial Date J. Jansen van Project Officer Checked Final Copy J.J.V.R 16 April 07 Rensburg G. Momber Project Specialist Checked Final Copy GM 18 April 07 J. Satchell Project Manager Authorised final J.S 23 April 07 Copy Maritime Archaeology Ltd Project No 1770 2 Room W1/95, National Oceanography Centre, Empress Dock, Southampton. SO14 3ZH. www.maritimearchaeology.co.uk SEA8 Technical Report – Marine Archaeological Heritage ______________________________________________________________ Contents I LIST OF FIGURES ......................................................................................................5 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................7 1. NON TECHNICAL SUMMARY................................................................................8 1.1 -

Broadcasting What the NAB Irgser Ds to Din Bout Sex and Violence

A roundup of honors earned by broadcasting What the NAB irgser ds to din bout sex and violence BroadcastingThe newsweekly of broadcasting and allied arts Our 46th Year 1977 Arb,00n. Apnl%Moy'». rSA. AOH. Adv. 55.49. Mon. n. 6:00 AM.I9,00 Midnight. All dota ore .bmoMS and frblecl to srr.ty lhtation.. Mr. fñovPublic Television is proud to be the recipient of five George Foster Peabody Awards -the best showing in all of broadcasting: 1 An innovative series of original A series of varied cultural A documentary on the problems of television dramas by new American performances from Washington's water utilization, presented on the playwrights. Wolf Trap Farm Park. PBS "Americana" series. Protletanu["' Prad,onsteam. VCET /Los Angeles Protlocaam WETA/Washington st. KERA/Da Ilas A series of historical dramas spanning A special report on the PBS 200 years of American history. "USA: People & Politics" series. P`=,:n7WNET surtan: /New York Protlucstatans: WETA/Washington & WNET /New York AMERICA'S PUBLIC TELEVISION STATIONS PUBLIC BROADCASTING SERVICE BroadcastingNJul4 The Week in Brief MORE TEETH IN CODE The NAB boards, meeting last Shiben notes FCC's new standards for screening week in Williamsburg, Va., had a busy four days. Standing employment practices are superior to those used in out was the television board's resolution calling for petitioners' screening. PAGE 29. stronger language against unacceptable programing. PAGE 20. NONDUPLICATION HANGUP The FCC has an inter - bureau split over criteria to be used for waivers. PAGE 31. FAMILY -VIEWING APPEALS Parties aggrieved with Judge Ferguson verdict file appeals. Department of CBS READING PROJECT Cooperative effort with local Justice contends FCC, Chairman Wiley did not pressure school board that has been tried by three network -owned broadcasters into accepting the plan. -

* Omslag Dutch Ships in Tropical:DEF 18-08-09 13:30 Pagina 1

* omslag Dutch Ships in Tropical:DEF 18-08-09 13:30 Pagina 1 dutch ships in tropical waters robert parthesius The end of the 16th century saw Dutch expansion in Asia, as the Dutch East India Company (the VOC) was fast becoming an Asian power, both political and economic. By 1669, the VOC was the richest private company the world had ever seen. This landmark study looks at perhaps the most important tool in the Company’ trading – its ships. In order to reconstruct the complete shipping activities of the VOC, the author created a unique database of the ships’ movements, including frigates and other, hitherto ignored, smaller vessels. Parthesius’s research into the routes and the types of ships in the service of the VOC proves that it was precisely the wide range of types and sizes of vessels that gave the Company the ability to sail – and continue its profitable trade – the year round. Furthermore, it appears that the VOC commanded at least twice the number of ships than earlier historians have ascertained. Combining the best of maritime and social history, this book will change our understanding of the commercial dynamics of the most successful economic organization of the period. robert parthesius Robert Parthesius is a naval historian and director of the Centre for International Heritage Activities in Leiden. dutch ships in amsterdam tropical waters studies in the dutch golden age The Development of 978 90 5356 517 9 the Dutch East India Company (voc) Amsterdam University Press Shipping Network in Asia www.aup.nl dissertation 1595-1660 Amsterdam University Press Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters The development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) shipping network in Asia - Robert Parthesius Founded in as part of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Amsterdam (UvA), the Amsterdam Centre for the Study of the Golden Age (Amsterdams Centrum voor de Studie van de Gouden Eeuw) aims to promote the history and culture of the Dutch Republic during the ‘long’ seventeenth century (c. -

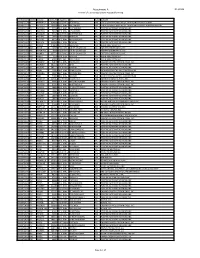

Attachment a DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing

Attachment A DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing File Number Service Callsign Facility ID Frequency City State Licensee 0000072254 FL WMVK-LP 124828 107.3 MHz PERRYVILLE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMN. 0000072255 FL WTTZ-LP 193908 93.5 MHz BALTIMORE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 0000072258 FX W253BH 53096 98.5 MHz BLACKSBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072259 FX W247CQ 79178 97.3 MHz LYNCHBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072260 FX W264CM 93126 100.7 MHz MARTINSVILLE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072261 FX W279AC 70360 103.7 MHz ROANOKE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072262 FX W243BT 86730 96.5 MHz WAYNESBORO VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072263 FX W241AL 142568 96.1 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072265 FM WVRW 170948 107.7 MHz GLENVILLE WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072267 AM WESR 18385 1330 kHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072268 FM WESR-FM 18386 103.3 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072270 FX W289CE 157774 105.7 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072271 FM WOTR 1103 96.3 MHz WESTON WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072274 AM WHAW 63489 980 kHz LOST CREEK WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072285 FX W206AY 91849 89.1 MHz FRUITLAND MD CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. 0000072287 FX W284BB 141155 104.7 MHz WISE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072288 FX W295AI 142575 106.9 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072293 FM WXAF 39869 90.9 MHz CHARLESTON WV SHOFAR BROADCASTING CORPORATION 0000072294 FX W204BH 92374 88.7 MHz BOONES MILL VA CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. -

Preliminary List of Dutch Naval Vessel Built Or Required in the Period 1700-1799

Preliminary list of Dutch naval vessel built or required in the period 1700-1799 Ron van Maanen As a working paper the layout is temporarily and the sources are excluded. no. 1, gaffship, admirality Maze, hired 1793-1799, monthly ¦ 300, 4 guns, 40 men. no. 1, gunsloop, admirality Zeeland, mentioned 1795. no.1, gaffschuyt, admiralty Maze, mentioned 1793. no.1, gaffship, departement Rotterdam, hired 1799-1801, returned to owner, 4 guns. no. 1, gungalliot, department Amsterdam built 1798, broken up 1809, 7 guns. no. 2, gaffship/-schuyt, admirality Maze, hired 1793-1799 monthly ¦ 300,-, 4 guns, 40 men. no. 2, gaffelaar, departement Rotterdam, hired 1799, returned to owner, 4 guns. no.2, gungalliot, department Amsterdam built 1798, broken up 1810. 7 guns. no. 3, gaffship, admiralty Maze, hired 1793-1795, 4 guns, 40 men. uitlegger no. 4, admiralty Maze, hired 1793-1793, 4 guns, 40 men. gaffship no. 4, mentioned 1798, paid off, 4 guns gaffelaar no. 4, department Rotterdam hired 1799, returned to owner 1800, 4 guns. gaffship no. 5, admiralty Maze, mentioned 1793-1798, 4 guns, 40 men gunhooker no. 5, admiralty Zeeland, mentioned 1795. gaffelaar no. 5, department Rotterdam hired 1799, returned to owner 1800, 4 guns. gaffship no. 6, admiralty Maze, mentioned 1793-1798, 4 guns, 40 men. gunhooker no. 6, admirality Zeeland, mentioned 1795. gaffelaar no. 6, department Rotterdam, hired 1799, returned to owners 1800, 4 guns. gaffship no. 7, admiralty Maze, mentioned >1794-1798<, 4 guns. gunhooker no. 7, admirality Zeeland, mentioned 1795. Preliminary list of Dutch naval vessel built or required in the period 1700-1799. -

Guide to the William A. Baker Collection

Guide to The William A. Baker Collection His Designs and Research Files 1925-1991 The Francis Russell Hart Nautical Collections of MIT Museum Kurt Hasselbalch and Kara Schneiderman © 1991 Massachusetts Institute of Technology T H E W I L L I A M A . B A K E R C O L L E C T I O N Papers, 1925-1991 First Donation Size: 36 document boxes Processed: October 1991 583 plans By: Kara Schneiderman 9 three-ring binders 3 photograph books 4 small boxes 3 oversized boxes 6 slide trays 1 3x5 card filing box Second Donation Size: 2 Paige boxes (99 folders) Processed: August 1992 20 scrapbooks By: Kara Schneiderman 1 box of memorabilia 1 portfolio 12 oversize photographs 2 slide trays Access The collection is unrestricted. Acquisition The materials from the first donation were given to the Hart Nautical Collections by Mrs. Ruth S. Baker. The materials from the second donation were given to the Hart Nautical Collections by the estate of Mrs. Ruth S. Baker. Copyright Requests for permission to publish material or use plans from this collection should be discussed with the Curator of the Hart Nautical Collections. Processing Processing of this collection was made possible through a grant from Mrs. Ruth S. Baker. 2 Guide to The William A. Baker Collection T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Biographical Sketch ..............................................................................................................4 Scope and Content Note .......................................................................................................5 Series Listing -

Directory of Radio Braddock Heights Brunswick Catonsville Crisfield

Maryland Directory of Radio Berlin Sports. News staff: one. Target aud: 25 -54. Spec prog: Relg 5 hrs Licensee: WTBO -WKGO Corp. LLC. Group owner. Wooster Republican wkly. *Troy D. Hill, gen mgr, Shane Walker, opns mgr; Shan Sheriff, Printing Co. Population served: 2,000,000 Natl. Network: Westwood progmg dir; Mike Delmer, news dir; Bryan Harz, engrg dir; Dwight One. Format: Classic rock, new rock. News staff: one; News: one hr WOCO(FU) June 25, 1981: 103.9 mhz; 3 kw. 328 ft TL: N38 22 58 - Cromwell, reporter; Bob Kinnamon, sports cmtr. wkly. Target aud: 25 -54. Richard Cornwell, adv mgr; Jim Van, local W75 18 58. Stereo. Hrs open: 24 20200 DuPont Blvd., Georgetown, news ed; Mark St. John, disc jockey; Ray Wagner, disc jockey; Tim 19947. Fax: (302) 856 -7633. Web Site: www.oc104.com. Licensee: Martin, disc jockey. Great Scott Broadcasting. Group owner: Great Scott Broadcasting acq WCEM -FM- Jan 29, 1968; 1063 mhz; 6 kw. Ant 325 ft TL: N38 35 11 -7 -97; $2.775 million). Population served: 228,000 Format RhythmicJCHR. 03 W76 04 54. Stereo. Hrs open: 2 Bay Street, 21613. Secondary News staff: one; News: 4 hrs wkly. Target aud: 18-49. Sue Tramons, address: Box 237 21613. Phone: (410) 228 -4800. Fax: (410) 228 -0130. WROG(FM)- 1948: 102.9 mhz; 32 kw. Mt 1,440 ft TL: N39 34 56 gen mgr. E -mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.mtslive.com. (Acq 1993; W78 53 53. Stereo. His open: 24 516 White Ave., 21502. Plane: (301) FIR: 8-23-93). -

Gresham College

GRE SHA M . co Reproduction of this tefi, or any efiract from it, must credit Gresham College THE SKY’S THE LIMIT! A Lectire by PROFESSOR HEATHER COUPER BSC DLitt(Hon) FRAS Gresham Professor of Astronomy 16 November 1994 .,, . .. .,,... .,..’.. -. , i GRESH.4.bI COLLEGE Policy & Objectives h independently funded educational institution, Gresham College exists . to continue the free public lectures which have been given for 400 years, and to reinterpret the ‘new lehg’ of Sir ~omas Gresham’s day in contemporary terms; to engage in study, teaching and research, particularly in those disciplines represented by the Gresham Professors; to foster academic consideration of contemporary problems; to challenge those who live or work in the City of London to engage in intellectual debate on those subjects in which the City has a proper concern; and to provide a window on the City for le-ed societies, both national and international. GreshamCollege,Barnard’sInn Hall, Holbom, LondonEClN 2HH Tel: 020783 I 0j75 Fax: 02078315208 e-mail:[email protected] THE SKY’S THE LIMIT! Professor Heather Couper Why do astronomers do astronomy? A lot of people (especially cynical journalists) ask me this question. It’s often assumed that astronomy - at best - is the useless pursuit of measuring the positions of stars in the sky, or - at worst - is something to do with being engaged in a secret follow-up to President Reagan’s Star Was military prograrnme. Whatever, astronomy is believed to be other-worldly, irrelevant, a waste of money, and something that is only studied by old men with long white beards. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 471 391 CS 511 612 AUTHOR McClure, Amy A., Ed.; Kristo, Janice V., Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K--Grade 6. 13th Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-0073-2 ISSN ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 579p.; Foreword by Rudine Sims Bishop. For the 12th Edition, see ED 437 668. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock no. 00732-1659: $29.95 NCTE members; $39.95 nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF03/PC24 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Childrens Literature; Cultural Context; Elementary Education; *Fiction; *Nonfiction; Picture Books; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Material Selection IDENTIFIERS *Information Books ABSTRACT In this 13th edition of "Adventuring with Books," teachers and librarians will find descriptions of more than 850 texts (published between 1999 and 2001) suitable for student use in background research, unit study, or pleasure reading, and children will find books that delight, amuse, and entertain. The texts described in the book are divided into 24 general topics, including Science Nonfiction; Struggle and Survival; Fantasy Literature; Sports; Games and Hobbies; and Mathematics in Our World. To highlight literature that reflects the schools' multiple ethnicities, the booklist also introduces readers to recent literature that celebrates African American, Asian and Pacific Island, Hispanic American, and indigenous cultures. Each chapter begins with a brief list of selection criteria, a streamlined list of all annotated titles in that chapter, and an introduction in which chapter editors discuss their criteria and the status of available books in that subject area.