Rebel in Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rural Radio Network

ROBERT MOORE a!r1u!uullululu!uulrl!! imi! 11111111! ml! ll! lluum!! mllmlmlllllul !llHml!lumlulllulllul! SELLING NEWS Heads Transradio Press WIKY Tells Audience Why ROBERT E. L. MOORE, vice pres- ident Press Service -AM -FM of Transradio LISTENERS to WIKY since 1945, has been elected presi- FOR Evansville, Ind., 9 a.m. newscasts dent of the corporation, Herbert i]l101p -rv 11'1 p' n1111,opra1rl1;i1j1 It explana- were introduced to daily Moore, founder of whys and wherefores tions of the the company and JOE Mutual recent two - CUMMISKEY, former of radio news during a board chairman, sportscaster, joins WPAT Pater- week sponsorless interlude, the sta- announced last son, N. J., as director of news, tion reports. week. He suc- sports and special events. He form- Purpose of the one -minute "les- ceeds Dixon Stew- erly was featured on Mutual's Inside sons" -the time slot on sponsor- art, Transradio's Sports, was once sports editor of now hiatus for the five-minute news- defunct New York PM and before that president since Ten major farm organizations cast -was to explain "why WIKY on staffs of the NewYork News and they 1945, who has the Buffalo Times. (Grange, etc.) representing 140,- newscasts are different," why been given a new 000 New York state families own of JACK JUREY named news editor of are listened to, the job radio assignment in the Rural Radio Network. Since they for WKBN Youngstown, Ohio. listen first to their network, make news and how news is gathered field of visual a broadcast, John Munger, news Mr. -

Wilkinsburg Williamsport Wyomissing York

WBAX Sports [Repeats: WEJL 630] WPTC Modern Rock* 1240 1000/ 1000 ND 88.1 494w -331ft York +Shamrock Communications Pennsylvania College of Technology WSBA Talk Sister to: WEJL, WEZX, WPZX, WQFM, WQFN 570-327-3761 fax: 570-320-2423 910 5000/ 1000 DA-2 570-961-1842 fax: 570-346-6038 1 College Ave, 17701 +Susquehanna Radio Corp. 149 Penn Ave, Scranton 18503 GM Brad Nason Sister to: WARM-F, WSOX GM Jim Loftus SM Tim Durkin www.pct.edu/wptc/ 717-764-1155 fax:717-252-4708 PD Michael Neff CE Kevin Fitzgerald Williamsport Market PO Box 910, 17402 www.wejl-wbax.com 5989 Susquehanna Plz Dr, 17406 Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Arbitron 0.2 Shr 200 AQH WVYA News / Variety* [Repeats: WVIA-F 89.9] 89.7 3300w -16ft DA GM Thomas Ranker SM Tina Heim WRKC Variety* Northeast PA Ed. TV Associates PD Jim Horn CE Bob Poff 88.5 440w -470ft 570-655-2808 fax:570-655-1180 www.wsba910.com York Arbitron 3.0 Shr 1700 AQH King's College 100 WVIA Way, Pittston 18640 2nd market Lancaster 570-208-5821 GM A. William Kelly SM Molly Worrell 133 N Franklin St, Wilkes Barre 18701 PD Larry Vojtko CE Joe Glynn WQXA Traditional Country GM Sue Henry PD Pete Phillips www.wvia.org 1250 1000133 ND www.kings.edu/wrkc/ Williamsport Market +Citadel Communications Corp. ScrantonAVilkes-Barre Market WCRG Contemporary Christian* [Repeats: WGRC 91.3] Sister to: WCAT-F, WCPP, WQXA-F WCLH Variety* 90.7 3000w -217ft 717-367-7700 fax:717-367-0239 90.7 175w 1020ft +Salt & Light Media Ministries 919 Buckingham Blvd, Elizabethtown 17022 Wilkes College 570-523-1190 fax:570-523-1114 GM Bob Adams SM Mike Stotsky 570-408-5907 fax: 570-408-5908 101 Armory Blvd, Lewlsburg 17837 PD Tim Michaels CE Richard Hill 84 W South St, Wilkes Barre 18766 GM/PD Larry Weidman CE Lamar Smith York Arbitron 1.1 Shr 600 AQH GM Renee Loftus SM Dennis Beishl www.wgrc.com WOYK Sports PD Jillian Ford CEBobReite Williamsport Market 5000/ 1000 DA-1 www.wclh.net 1350 +Starvlew Media, Inc. -

![Volume 51 Issue 04 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6781/volume-51-issue-04-pdf-1646781.webp)

Volume 51 Issue 04 [PDF]

Cornell Alumni News Volume 51, Number 4 October 15, 1948 Price 25 Cents Johnny Parson Club on Beebe Lake Bollinger '45 and persistence conquer all things"—BENJAMIN FRANKLIN Why power now serves us better When it comes to power, the dreams of our childhood are home . approaching man's dreams for the future through fast becoming a reality. For no matter what our needs, spe- research and engineering. This also takes such materials as cial motors or engines are now designed to meet them. carbon . from which the all-important graphite, used to From the tiny thumb-sized motors in electric razors — "control" the splitting atom, is made. and the surge of the engines in our cars—to the pulsing tur- The people of Union Carbide produce materials that help bines that propel our ocean liners . today's power is bet- science and industry improve the sources and uses of power ter, more dependable than ever before. And these advances ...to help maintain American leader- were brought about by research and engineering . and ship in meeting the needs of mankind. by today's better materials. FREE : You are invited to send for the neiv i lus- Examples? Better metals for giant turbines and genera- trated booklet, '"''Products and Processes,''' which shows how science and industry use L CC's tors, improved transformers and transmission lines. Stain- Alloys, Chemicals, Carbons, Gases and Plastics. less steel, resistant to rust and corrosion. Better plastics that make insulation fire-resistant, and more flexible and wear- proof . for the millions of miles of wires it takes to make power our servant. -

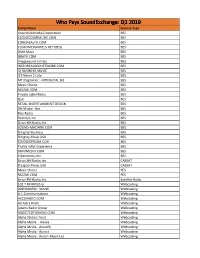

Who Pays SX Q3 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q3 2019 Entity Name License Type AMBIANCERADIO.COM BES Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES F45 Training Incorporated BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It's Never 2 Late BES Jukeboxy BES MANAGEDMEDIA.COM BES MIXHITS.COM BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES Music Maestro BES Music Performance Rights Agency, Inc. BES MUZAK.COM BES NEXTUNE.COM BES Play More Music International BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Startle International Inc. BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio #1 Gospel Hip Hop Webcasting 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 411OUT LLC Webcasting 630 Inc Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting AD VENTURE MARKETING DBA TOWN TALK RADIO Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting africana55radio.com Webcasting AGM Bakersfield Webcasting Agm California - San Luis Obispo Webcasting AGM Nevada, LLC Webcasting Agm Santa Maria, L.P. Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting -

The Ithacan, 1951-10-19

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1951-52 The thI acan: 1950/51 to 1959/60 10-19-1951 The thI acan, 1951-10-19 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1951-52 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 1951-10-19" (1951). The Ithacan, 1951-52. 2. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1951-52/2 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1950/51 to 1959/60 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1951-52 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. CORTLAND GAME GIVE TO THE TONIGHT RED FEATHER HERE tttalt CAMPAIGN Vol. 23, No. 3 Ithaca College, Ithaca, New York, October 19, 1951 Oracle Sponsored WIT J Return To Air Marked Student Loan Fund Central Theme Highlights Again Available By Intensified Programming The Dean's' Loan Fund and the fund sponsored by Oracle are again avail Frosh Frolics Of .1951 Ith.tea College's radio station, WITJ, returned. to the air ~onday evening, Oct. 15, with a I?umber of ~e.V.: programs designed to acquaint ~he able to Ithaca College Students. Differing from former years, Frosh Frolics, a show produced by community more fully with. t~e a~tivm~s of t~e Co\\ege~ as we\\ as to give The purpose of the Dean's Loan freshman girls at Ithaca College will be typed around a central theme. students more thorough trammg m radio stat10n operation. Fund, founded by the Ithaca College To provide a unifying climax, a finale involving members of all departments This semester, WIT.T will broadcast Woman's Club, is to put at the disposal will be presented. -

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media -

Alwood, Edward, Dark Days in the Newsroom

DARK DAYS IN THE NEWSROOM DARK DAYS in the NEWSROOM McCarthyism Aimed at the Press EDWARD ALWOOD TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia Temple University Press 1601 North Broad Street Philadelphia PA 19122 www.temple.edu/tempress Copyright © 2007 by Edward Alwood All rights reserved Published 2007 Printed in the United States of America Text design by Lynne Frost The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Alwood, Edward. Dark days in the newsroom : McCarthyism aimed at the press / Edward Alwood. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 13: 978-1-59213-341-3 ISBN 10: 1-59213-341-X (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 13: 978-1-59213-342-0 ISBN 10: 1-59213-342-8 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Anti-communist movements—United States—History—20th century. 2. McCarthy, Joseph, 1908–1957—Relations with journalists. 3. Journalists— United States—History—20th century. 4. Journalists—United States— Political activity—History—20th century. 5. Press and politics—United States—History—20th century. 6. United States—Politics and government— 1945–1953. 7. United States—Politics and government—1953–1961. I. Title. E743.5.A66 2007 973.921—dc22 2006034205 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 In Memoriam Margaret A. Blanchard Teacher, Mentor, and Friend Do the people of this land . desire to preserve those so carefully protected by the First Amendment: Liberty of religious worship, freedom of speech and of the press, and the right as freemen peaceably to assemble and petition their government for a redress of grievances? If so, let them withstand all beginnings of encroachment. -

(Annual) Costs; the Third Vector Presents Cost As a Function of Environment

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 024 286 64 EM 007 013 Cost Study of Educational Media Systems and Their Equipment Components. Volume II, Technical Report. Final Repor t. General Learning Corp., Washington, D.C. Spons Agency-Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. Bureau of Research. Bureau No- BR- 7-9006 Pub Date Jun 68 Contract- OEC- 1- 7-079006-5139 Note- 334p. EDRS Price MF-S1.25 HC-$16.80 Descriptors- Airborne Television, Capital Outlay (for Fixed Assets), Closed Circuit Television, Dial Access Information Systems,EducationalEnvironment,*EquipmentWilization,*Estimated Costs,Films,Initial Expenses, *Instructional Media, Instructional Technology, Instructional Television, Language Laboratories, Learning Laboratories, *Media Technology, Operating Expenses, Radio, *Technical Reports, Video Tape Recordings A common instrucrionaltask and a set of educational environments are hypothesized for analysis of media cost data.The analytic structure may be conceptulized as a three-dimensional matrix: the first vector separates costs into production, distribution, and reception; the second vector delineates capital (initial) and operating (annual) costs; the third vector presents cost as a function of environment. Per studentequivalentannualcosts are estimatedfor airborne television,InstructionalTelevisionFixed Service(ITFS),satellitetelevision, UHF television, closed circuittelevision,video tape recordings,film,radio, language laboratories, and dial access systems. The appendix analyzes componential and operating costs for five media systems (instructional television, audiovisual media system1 educational radio, learning and language laboratories, dial access), using guidelines established in VolumeI of the study. Estimated costs are presented graphically with price ranges and design considerations. Researchers must examine the possibilities of cost savings in media development and consider the relationship of instructional technology to the educational system, government, and the knowledge industry. -

The Times Square Zipper and Newspaper Signs in an Age Of

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive All Faculty Publications 2018-02-01 News in Lights: The imesT Square Zipper and Newspaper Signs in an Age of Technological Enthusiasm Dale L. Cressman PhD Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Original Publication Citation Dale L. Cressman, "News in Lights: The imeT s Square Zipper and Newspaper Signs in an Age of Technological Enthusiasm," Journalism History 43:4 (Winter 2018), 198-208 BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Cressman, Dale L. PhD, "News in Lights: The imeT s Square Zipper and Newspaper Signs in an Age of Technological Enthusiasm" (2018). All Faculty Publications. 2074. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/2074 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. DALE L. CRESSMAN News in Lights The Times Square Zipper and Newspaper Signs in an Age of Technological Enthusiasm During the latter half of the nineteenth century, when the telegraph had produced an appetite for breaking news, New York City newspaper publishers used signs on their buildings to report headlines and promote their newspapers. Originally, chalkboards were used to post headlines. But, fierce competition led to the use of new technologies, such as magic lantern projections. These and, later, electrically lighted signs, would evoke amazement. In 1928, during an age of invention, the New York Times installed an electric “moving letter” sign on its building in Times Square. -

Undergraduate Student Handbook 2019

UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT HANDBOOK 2019 - 2020 Property of_______________________________________________________ Phone__________________________________________________________ In case of emergency, please notify: Name__________________________________________________________ Phone__________________________________________________________ Please Note: Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information presented in this handbook. All event schedules were obtained in spring 2019, and therefore, are subject to change. If you have any questions or suggestions for next year’s calendar, please contact the Office of Enrollment Management and Student Affairs, 319 Ulmer Hall, Lock Haven, PA 17745. An Official Publication LOCK HAVEN UNIVERSITY LOCK HAVEN, PENNSYLVANIA TABLE OF CONTENTS LHU Mission & Vision .....................................................................................................................1 Nondiscrimination ......................................................................................................................... 1-5 Academic Matters ....................................................................................................................... 5-13 Services for Students ................................................................................................................. 13-24 Residence Hall/Suite/Apartment Living .................................................................................... 24-25 Important Policies Governing Residence Halls/ Suites/Apartments -

Fall Newsletter 2018

South Williamsport Area School District FALL NEWSLETTER 2018 An Equal Opportunity Employer in Compliance with Title VI, Title IX, and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. South Williamsport Area School District Newsletter FALL 2018 A Letter from the Superintendent In August 2018, the district launched a new comprehensive strategic plan aligned with current trends in education nationally, and designed to meet changing Newsletter • FALL 2018 local demands. The vision for the district is based on seven strategic imperatives BOARD OF at the elementary and at the secondary SCHOOL DIRECTORS level. The elementary plan is focused on Chris Branton – President core academic and social learning where ([email protected]) the secondary plan priorities innovation, Region III risk, and career trajectories. The strategic Gregg Anthony – Vice President ([email protected]) plan represents a collaborative approach Region II by multiple committees and staff input Cathy Bachman over eighteen months of planning. It is ([email protected]) a growth orientated model that seeks to Region III leverage every opportunity to increase Sue Davenport students’ engagement and learning. ([email protected]) However, as bold as the vision is, it must be Region III supported by the commitment to robust Nathan Miller – Treasurer resources to leverage the full potential of • Central Elementary is expanding ([email protected]) the vision. the impact of its Positive Behavior Region I Intervention and Support program Erica Molino With the new district plan at the center by adding additional layers of student ([email protected]) of the conversation, the school board supports and staff training. Region II approved a budget of 19.8 million dollars. -

Who's Who in the Media Cartel

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 24, Number 4, January 17, 1997 if not stopped, will escalate even more rapidly, as the result III. Corporate Profiles of the federal government'scapitulation to the "deregulation" frenzy. Deregulation spells cartelization, and a growing tyr anny of censorship and manipulation of how you think and what you know. For purposes of clarity, we have grouped the corporate profiles into two categories: those companies under direct Who's who in British control, and those controlled by British-allied, Ameri can entities. the media cartel Clearly, there are genuine differences of policy, among these media giants. There have also been substantial policy differences between the Clinton administration and the Brit The brief profiles that follow illustrate the point that has been ish interests, which have periodically exploded into the me made throughout this report: that an increasingly British dia. Media control and manipulation, as we have shown, does dominated, highly centralized group of powerful individuals not mean that a monolithic "Big Brother" serves up one, and and multinational companies dominates the American news only one distorted version of reality. The media cabal defines media. The rate of consolidation of power is escalating-and, the boundary conditions of the "news," and, therefore, shapes broadcasting; they apparently succeeded in eliminating the provision in the House version that would have raised this 50% New communications bill particular limit to after one year. • The federal limit on no one entity owning more than furthers cartelization 20 AM plus 20 FM radio stations has been eliminated entirely. Caps are placed on four levels of local markets; for example, in a market with 45 or more radio stations, On Feb.