The Art of Networking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Healthcare Riskops Manifesto

The Healthcare RiskOps Manifesto “Committees are, by nature, timid. They are based on the premise of safety in numbers; content to survive inconspicuously, rather than take risks and move independently ahead. Without independence, without the freedom for new ideas to be tried, to fail, and to ultimately succeed, the world will not move ahead, but rather live in fear of its own potential” Ferdinand Porsche And you may ask yourself, "How do I work this?" And you may ask yourself, "Where is that large automobile?" And you may tell yourself, "This is not my beautiful house." And you may tell yourself, "This is not my beautiful wife." David Byrne The End is Near “People of Earth, hear this!” A specter is haunting healthcare. And we’ve got work to do. It’s about challenging the old assumptions of managing risk because nothing has changed. Yet, everything has changed. It’s about heralding a new vision because the old one doesn’t work. Change creates opportunities. Change drives outcomes. And healthcare needs secure outcomes. Healthcare risk needs change. We must challenge assumptions: identity, role, purpose, place, power. Change built on strong beliefs that will upset the status quo. We don’t care. We are focused on moving the industry forward. Le risque est avant-gardiste. Futurism. Vorticism. Dada. Surrealism. Situationism. Neoism. Risk the Elephant. Uncaged. Risk is Nazaré. It’s a red balloon. Risk is sunflower fields. And fire on the mountain. Risk guides the first decision. It’s as old as Eden. Fight. Or flight. Risk is nucleotide. To ego. -

Agregue Y Devuelva, MAIL ART En Las Colección Del MIDE-CIANT/UCLM

AGREGUE Y DEVUELVA MAIL ART en las colecciones del MIDE-CIANT/UCLM © de los textos e ilustraciones: sus autores. © de la edición: Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha. Textos de: José Emilio Antón, Ibírico, Ana Navarrete Tudela, Sylvia Ramírez Monroy, César Reglero y Pere Sousa. Edita: Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, MIDE-CIANT y Fundación Antonio Pérez. Colección CALEIDOSCOPIO n.º 17. Serie Cuadernos del Media Art. Dir.: Ana Navarrete Tudela Equipo de documentación: Ana Alarcón Vieco, Roberto J. Alcalde López y Clara Rodrigo Rodríguez. Fotografías: Montserrat de Pablo Moya Corrección de textos: Antonio Fernández Vicente I.S.B.N.: 978-84-9044-421-4 (Edición impresa) I.S.B.N.: 978-84-9044-422-1 (Edición electrónica) Doi: http://doi.org/10.18239/caleidos_2021.17.00 D.L.: CU 11-2021 Esta editorial es miembro de la UNE, lo que garantiza la difusión y comercialización de sus publicaciones a nivel nacional e internacional. Diseño y maquetación: CIDI (UCLM) Impresión: Trisorgar Artes Gráficas Hecho en España (U.E.) – Made in Spain (E.U.) Esta obra se encuentra bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons CC BY 4.0. Cualquier forma de reproducción, distribución, comunicación pública o transformación de esta obra no incluida en la licencia Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 solo puede ser realizada con la autorización expresa de los titulares, salvo excepción prevista por la ley. Puede Vd. acceder al texto completo de la licencia en este enlace: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.es EXPOSICIONES: Comisariado: Patricia Aragón Martín, Ana Navarrete Tudela, Montserrat de Pablo Moya Coordinación: Ana Navarrete Tudela Ayudantes de coordinación: Adoración Saiz Cañas, Ana Alarcón Vieco, Ignacio Page Valero Dirección de montaje: MIDE-CIANT/UCLM, Fundación Antonio Pérez, ArteTinta Digitalización: Ana Alarcón Vieco, Patricia Aragón y Clara Rodrigo Rodríguez Montaje y transporte: ArteTinta Centros: Sala ACUA, Cuenca. -

Real.Izing the Utopian Longing of Experimental Poetry

REAL.IZING THE UTOPIAN LONGING OF EXPERIMENTAL POETRY by Justin Katko Printed version bound in an edition of 20 @ Critical Documents 112 North College #4 Oxford, Ohio 45056 USA http://plantarchy.us REEL EYE SING THO YOU DOH PEON LAWN INC O V.EXPER(T?) I MEANT ALL POET RE: Submitted to the School of Interdisciplinary Studies (Western College Program) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy Interdisciplinary Studies by Justin Katko Miami University Oxford, Ohio April 10, 2006 APPROVED Advisor: _________________ Xiuwu Liu ABSTRACT Capitalist social structure obstructs the potentials of radical subjectivities by over-determining life as a hierarchy of discrete labors. Structural analyses of grammatical syntax reveal the reproduction of capitalist social structure within linguistic structure. Consider how the struggle of articulation is the struggle to make language work.* Assuming an analog mesh between social and docu-textual structures, certain experimental poetries can be read as fractal imaginations of anarcho-Marxist utopianism in their fierce disruption of linguistic convention. An experimental poetry of radical political efficacy must be instantiated by and within micro-social structures negotiated by practically critical attentions to the material conditions of the social web that upholds the writing, starting with writing’s primary dispersion into the social—publishing. There are recent historical moments where such demands were being put into practice. This is a critical supplement to the first issue of Plantarchy, a hand-bound journal of contemporary experimental poetry by American, British, and Canadian practitioners. * Language work you. iii ...as an object of hatred, as the personification of Capital, as the font of the Spectacle. -

Neoist Interruptus and the Collapse of Originality

Neoist Interruptus and the Collapse of Originality Stephen Perkins 2005 Presented at the Collage As Cultural Practice Conference, University of Iowa, March 26th, Iowa City Tracing the etymology of the word collage and its compound colle becomes a fascinating journey that branches out into a number of different directions all emanating from the act of gluing things together. After reading a number of definitions that detail such activities as sticking, gluing, pasting, adhering, and the utilization of substances such as gum (British), rubber cement (US) and fish glue, one comes upon another meaning of a rather different order. In France collage has a colloquial usage to describe having an affair, and colle more specifically means to live together or to shack up together.1 While I lay no great claims to any expertise in the area of linguistic history, I would suggest that this vernacular meaning of colle arises when living together would have generated far more excitement than the term, and the activity, generates today. And, while the dictionary definition of the word does not support the interpretation that I am going to suggest here, I would argue that its usage in its original context would have generated a very particular kind of frisson that would have been implicitly associated with the act of two people being collaged or glued together, in other words fucking, or to fuck, or simply fuck. What has this to do with a paper on collage as cultural intervention, you might ask? It’s simple really, well relatively. My subject is a late 20th century international avant-garde movement known as the Neoist Cultural Conspiracy (Neoism for short), which I would argue is the last of the historic avant-gardes of the 20th century. -

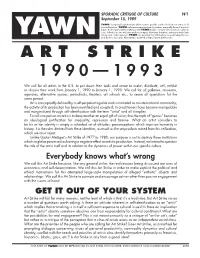

Artists in the U.S

SPORADIC CRITIQUE OF CULTURE Nº1 September 15, 1989 YAWN is a sporadic communiqué which seeks to provide a critical look at our culture in all its manifestations. YAWN welcomes responses from its readers, especially those of a critical nature. Be forewarned that anything sent to YAWN may be considered for inclusion in a future issue. Submissions are welcome and encouraged. Monetary donations are requested to help defray costs. Subscriptions to YAWN are available for $10 (cash or unused stamps) for one YAWN year by first class mail. All content is archived at http://yawn.detritus.net/. A R T S T R I K E 1 9 9 0 — 1 9 9 3 We call for all artists in the U.S. to put down their tools and cease to make, distribute, sell, exhibit or discuss their work from January 1, 1990 to January 1, 1993. We call for all galleries, museums, agencies, alternative spaces, periodicals, theaters, art schools etc., to cease all operations for the same period. Art is conceptually defined by a self-perpetuating elite and is marketed as an international commodity; the activity of its production has been mystified and co-opted; its practitioners have become manipulable and marginalized through self-identification with the term “artist” and all it implies. To call one person an artist is to deny another an equal gift of vision; thus the myth of “genius” becomes an ideological justification for inequality, repression and famine. What an artist considers to be his or her identity is simply a schooled set of attitudes; preconceptions which imprison humanity in history. -

Practices of Networking in Grassroots Communities from Mail Art to the Case of Anna Adamolo

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Article Volume 2 (2): 68 - 78 (November 2010) Bazzichelli, Critique of social networking Towards a critique of social networking: practices of networking in grassroots communities from mail art to the case of Anna Adamolo Tatiana Bazzichelli1 Abstract This article follows my reflections on the topic of networking art in grassroots communities as a challenge for socio-political transformation. It analyses techniques of networking developed in collective networks in the last half of the twentieth century, which inspired the structure of Web 2.0 platforms and have been used as a model to expand the markets of business enterprises. I aim to advance upon earlier studies on networked art, rejecting the widely accepted idea that social networking is mainly technologically determined. The aim is to reconstruct the roots of collaborative art practices in which the artist becomes a networker, a creator of shared networks that expand virally through collective interventions. The focus is collaborative networking projects such as the network of mail art and multiple identities projects such as the Luther Blissett Project (LBP), the Neoist network- web conspiracy and, referring to the contemporary scenario of social networking, the Italian case of Anna Adamolo (2008-2009). The Anna Adamolo case is presented as a clear example of how networking strategies, and viral communication techniques, might be used to generate political criticism both of the media (in this case of the social media) and society. This case study becomes even more relevant if framed by a long series of hacktivist practices realized in the Italian activist movement since the eighties, where collective and social interventions played a crucial role. -

Un Manifiesto Hacker

UN MANIFIESTO HACKER ALPHA. BET & GIMMEL McKENZIE WARK UN MANIFIESTO HACKER Traducción de Laura Mañero ALPHA DECAY Gracias a: AG, AR, BH, BL, CD, CF, el di funto CH, CL, CS, DB, DG, DS, FB, FS, GG, GL, HJ, IV, JB, JD, JF, JR, KH, KS, LW, MD, ME, MH, ML MT, MV, NR, OS, PM, RD, RG, RN, RS, SB, SD, SH, SK, SL, SS, TB, TC, TW. Versiones anteriores de Un manifiesto hacker aparecieron en Critical Secret, Feeler- gauge, Fibreculture Reader, Sarai Reader y Subsol In memoriam: Kathy Rey de los piratas Acker ÍNDICE Abstracción ..................................................................... 15 Clase.................................................................................. 23 Educación ....................................................................... 33 Hackear ........................................................................... 43 Historia ........................................................................... 53 Información..................................................................... 67 Naturaleza ....................................................................... 73 Producción....................................................................... 81 Propiedad ....................................................................... 89 Representación .............................................................. 103 Revuelta........................................................................... 113 Estado ............................................................................. 123 Sujeto.............................................................................. -

Situationist

Situationist The Situationist International (SI), an international political and artistic movement which has parallels with marxism, dadaism, existentialism, anti- consumerism, punk rock and anarchism. The SI movement was active in the late 60's and had aspirations for major social and political transformations. The SI disbanded after 1968.[1] The journal Internationale Situationniste defined situationist as "having to do with the theory or practical activity of constructing situations." The same journal defined situationism as "a meaningless term improperly derived from the above. There is no such thing as situationism, which would mean a doctrine of interpretation of existing facts. The notion of situationism is obviously devised by antisituationists." One should not confuse the term "situationist" as used in this article with practitioners of situational ethics or of situated ethics. Nor should it be confused with a strand of psychologists who consider themselves "situationist" as opposed to "dispositionist". History and overview The movement originated in the Italian village of Cosio d'Arroscia on 28 July 1957 with the fusion of several extremely small artistic tendencies, which claimed to be avant-gardistes: Lettrist International, the International movement for an imaginist Bauhaus, and the London Psychogeographical Association. This fusion traced further influences from COBRA, dada, surrealism, and Fluxus, as well as inspirations from the Workers Councils of the Hungarian Uprising. The most prominent French member of the group, Guy Debord, has tended to polarise opinion. Some describe him as having provided the theoretical clarity within the group; others say that he exercised dictatorial control over its development and membership, while yet others say that he was a powerful writer, but a second rate thinker. -

Santos, Osmar. Sassu, Antonio

233 2556 Geometric Landscape. Postcard by original collage work. Signed, dated: 1983. Not postal using. Rubberoid, Rudi ( J. S. Palmer). Box 2432, Bellingham, WA-98227 2557 Large white envelope covered with rubbers & stickers on both sides. To GP. Postmarking: 22:02:88 2558 <Sunshine envelope. 23x31 cm. light beige cover with a colourful collage work (sunrise) in the middle. Cut stamps and other accents. Sent to GP., 22:05:90 2559 Subversive Twilight Zone. Long-size envelope with rubbers and stickers. Back: Statement about „...abolish the arts...“ (text by a red rubber stamp). 2553 Sent to GP. 22:06:90 2560 Flower pots. Self-made postcard with an advertisement by cut & collage work. Sent to GP. 12:09:90 2561 Gonzo journalist. Long-size envelope with colourful rubbers. Sent to GP., 02:04:91 2555 2556 2562 Yellow Umbrella. Long-size envelope with a hand coloured frawing and colourful rubbers. Sent to GP., 06:06:91 2563 Foot Notes. Foot shaped paper with a handwritten letter to GP. Signed, dated: 5 December 1991 2564 Physicians Mutual. Small envelope with rubbers and stickers. Sent to GP. 07:10:93 2563 2559 a / b (Fragment) 234 Ruch, Günther. 315 Route de Peney, Genève-Peney. CH-1242 2565 Greetings from Genova. Offset card from ‘74 (100 copies). Back: letter to GP. Signed, n.d. (1984) 2566 3x Communication. Offset card from 1976. Back: mailed, signed to GH. Postmarking: 02:06:86 2467 Rose letter (this isn‘t a rose...). Poem-postcard, OUT-Press, offset, from 2557 1983. Back: letter to GP. Signed, dated: 15 - 1 - 91. -

1455189355674.Pdf

THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN Cover by: Peter Bradley LEGAL PAGE: Every effort has been made not to make use of proprietary or copyrighted materi- al. Any mention of actual commercial products in this book does not constitute an endorsement. www.trolllord.com www.chenaultandgraypublishing.com Email:[email protected] Printed in U.S.A © 2013 Chenault & Gray Publishing, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Storyteller’s Thesaurus Trademark of Cheanult & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Chenault & Gray Publishing, Troll Lord Games logos are Trademark of Chenault & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS 1 FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR 1 JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN 1 INTRODUCTION 8 WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT 8 THE STORYTeller’s RESPONSIBILITY: RESEARCH 9 WHAT THIS BOOK DOES NOT CONTAIN 9 A WHISPER OF ENCOURAGEMENT 10 CHAPTER 1: CHARACTER BUILDING 11 GENDER 11 AGE 11 PHYSICAL AttRIBUTES 11 SIZE AND BODY TYPE 11 FACIAL FEATURES 12 HAIR 13 SPECIES 13 PERSONALITY 14 PHOBIAS 15 OCCUPATIONS 17 ADVENTURERS 17 CIVILIANS 18 ORGANIZATIONS 21 CHAPTER 2: CLOTHING 22 STYLES OF DRESS 22 CLOTHING PIECES 22 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 24 CHAPTER 3: ARCHITECTURE AND PROPERTY 25 ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AND ELEMENTS 25 BUILDING MATERIALS 26 PROPERTY TYPES 26 SPECIALTY ANATOMY 29 CHAPTER 4: FURNISHINGS 30 CHAPTER 5: EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 ADVENTurer’S GEAR 31 GENERAL EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 2 THE STORYTeller’s Thesaurus KITCHEN EQUIPMENT 35 LINENS 36 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS -

9780816644629.Pdf

COLLECTIVISM AFTER ▲ MODERNISM This page intentionally left blank COLLECTIVISM ▲ AFTER MODERNISM The Art of Social Imagination after 1945 BLAKE STIMSON & GREGORY SHOLETTE EDITORS UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA PRESS MINNEAPOLIS • LONDON “Calling Collectives,” a letter to the editor from Gregory Sholette, appeared in Artforum 41, no. 10 (Summer 2004). Reprinted with permission of Artforum and the author. An earlier version of the introduction “Periodizing Collectivism,” by Blake Stimson and Gregory Sholette, appeared in Third Text 18 (November 2004): 573–83. Used with permission. Copyright 2007 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Collectivism after modernism : the art of social imagination after 1945 / Blake Stimson and Gregory Sholette, editors. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8166-4461-2 (hc : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8166-4461-6 (hc : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8166-4462-9 (pb : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8166-4462-4 (pb : alk. paper) 1. Arts, Modern—20th century—Philosophy. 2. Collectivism—History—20th century. 3. Art and society—History—20th century. I. Stimson, Blake. II. Sholette, Gregory. NX456.C58 2007 709.04'5—dc22 2006037606 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. -

Albert Einstein .Welcome!

“Creativity is more important than knowledge” - Albert Einstein .Welcome! The High School Art Classes are educational experiences centered around creativity in a structured, but fun and enjoyable atmosphere. They are designed for all students, not just the “naturally talented artist”. Don’t worry about it if you can’t draw or paint - that is why you are taking this class - to learn these skills. The following handbook for the art room is a policy/procedure guide for students to reference. This book is designed to help all students achieve their greatest potential in the art program by having a smooth and efficient running classroom. With this in mind, clear policies and procedures need to be set forth that affect the student, the class environment, fellow peers, the instructor, and the safety of all. If there are questions about the information set forth, please feel free to ask any time. Logistics POLICIES • Appropriate behavior is expected. School rules and policies are upheld. Simply use your best judgment. • Consequences are as stated in school policy (may include coming in for activity period, staying after school, detention, etc.). • Promote an environment which ensures a smooth running and enjoyable educational experience. In addition to the standard set of school rules, there are 6 additional general rules in the art room: 1) “Do those things which support your learning and the learning of others” - use your best judgment 2) Everyone’s ideas are valued - no one or their ideas are to be put down or made fun of. You must feel comfortable taking chances and exploring artistic ideas in an inviting atmosphere.