Transit System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

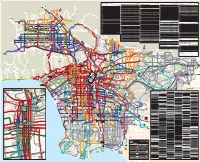

Metro Bus and Metro Rail System

Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Metro Bus Lines East/West Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays North/South Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Limited Stop Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Special Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Approximate frequency in minutes Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Weekdays Saturdays Sundays 102 Walnut Park-Florence-East Jefferson Bl- 200 Alvarado St 5-8 11 12-30 10 12-30 12 12-30 302 Sunset Bl Limited 6-20—————— 603 Rampart Bl-Hoover St-Allesandro St- Local Service To/From Downtown LA 29-4038-4531-4545454545 10-12123020-303020-3030 Exposition Bl-Coliseum St 201 Silverlake Bl-Atwater-Glendale 40 40 40 60 60a 60 60a 305 Crosstown Bus:UCLA/Westwood- Colorado St Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve 3045-60————— NEWHALL 105 202 Imperial/Wilmington Station Limited 605 SANTA CLARITA 2 Sunset Bl 3-8 9-10 15-30 12-14 15-30 15-25 20-30 Vernon Av-La Cienega Bl 15-18 18-20 20-60 15 20-60 20 40-60 Willowbrook-Compton-Wilmington 30-60 — 60* — 60* — —60* Grande Vista Av-Boyle Heights- 5 10 15-20 30a 30 30a 30 30a PRINCESSA 4 Santa Monica Bl 7-14 8-14 15-18 12-18 12-15 15-30 15 108 Marina del Rey-Slauson Av-Pico Rivera 4-8 15 18-60 14-17 18-60 15-20 25-60 204 Vermont Av 6-10 10-15 20-30 15-20 15-30 12-15 15-30 312 La Brea -

Staff Report

Staff Report TO: Mayor, and City Council Members FROM: Elizabeth Gibbs, Director of Community Services DATE February 4, 2020 SUBJECT: Opposition Letter – SunLine Transit Agency Proposed Commuter Link Route 10 Background and Analysis: On November 7, 2019, SunLine Transit Agency (SunLine) announced to the Transportation Now (T-Now) committee that they had completed a new draft schedule for their Commuter Link 220, which provides service from Palm Desert to the Riverside Metrolink Station, with stops at Casino Morongo and Beaumont Walmart (Attachment A). On November 12, 2019, SunLine held a community meeting at the Beaumont Civic Center and presented a proposed new commuter link route with service from the Coachella Valley to California State University San Bernardino’s (CSUSB) main campus in San Bernardino, with a stop at Beaumont Walmart (Attachment B). SunLine presented their proposal as follows: Current Service - Three (3) eastbound and three (3) westbound trips from Coachella Valley to Riverside, - FY 19 ridership was 13,561 passenger trips, Proposed Service - Four (4) eastbound and four (4) westbound trips from Coachella Valley to San Bernardino, and - Target passengers are CSUSB students. Following the community meeting, City staff contacted SunLine staff and requested a meeting to discuss the proposed route to gain more information about future service; however, no response was received. On January 9, 2020, SunLine staff emailed a draft support letter for their grant application for a solar microgrid to hydrogen transit project. In the letter, they introduced a new Commuter Link Route 10 bus service from Indio to San Bernardino, with stops at Beaumont Walmart and the San Bernardino Transit Center (SBTC) (Attachment C). -

Regional Transit Technical Advisory Committee October 29, 2014 Full

MEETING OF THE REGIONAL TRANSIT TECHNICAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE Wednesday, October 29, 2014 10:00 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. SCAG Los Angeles Main Office 818 W. 7th Street, 12th Floor, Policy Committee Room A Los Angeles, California 90017 (213) 236-1800 Teleconferencing Available: Please RSVP with Ed Rodriguez at [email protected] 24 hours in advance. Videoconferencing Available: Orange SCAG Office Ventura SCAG Office 600 S. Main St, Ste. 906 Orange, CA 92863 950 County Square Dr, Ste 101 Ventura, CA 93003 Imperial SCAG Office Riverside SCAG Office 1405 North Imperial Ave., Suite 1 , CA 92243 3403 10th Street, Suite 805 Riverside, CA 92501 SCAG San Bernardino Office 1170 W. 3rd St, Ste. 140 San Bernardino, CA 92410 If members of the public wish to review the attachments or have any questions on any of the agenda items, please contact Matt Gleason at (213) 236-1832 or [email protected]. REGIONALTRANSIT TECHNICAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE AGENDA October 29, 2014 The Regional Transit Technical Advisory Committee may consider and act upon any TIME PG# of the items listed on the agenda regardless of whether they are listed as information or action items. 1.0 CALL TO ORDER (Wayne Wassell, Metro, Regional Transit TAC Chair) 2.0 PUBLIC COMMENT PERIOD - Members of the public desiring to speak on items on the agenda, or items not on the agenda, but within the purview of the Regional Transit Technical Advisory Committee, must fill out and present a speaker’s card to the assistant prior to speaking. Comments will be limited to three minutes. -

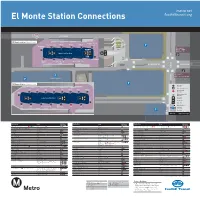

El Monte Station Connections Foothilltransit.Org

metro.net El Monte Station Connections foothilltransit.org BUSWAY 10 Greyhound Foothill Transit El Monte Station Upper Level FT Silver Streak Discharge Only FT486 FT488 FT492 Eastbound Metro ExpressLanes Walk-in Center Discharge 24 25 26 27 28 Only Bus stop for: 23 EMT Red, EMT Green EMS Civic Ctr Main Entrance Upper Level Bus Bays for All Service B 29 22 21 20 19 18 Greyhound FT481 FT Silver Streak Metro Silver Line Metro Bike Hub FT494 Westbound RAMONA BL RAMONA BL A Bus stop for: EMS Flair Park (am/pm) Metro Parking Structure Division 9 Building SANTA ANITA AV El Monte Station Lower Level 1 Bus Bay A Bus Stop (on street) 267 268 487 190 194 FT178 FT269 FT282 2 Metro Rapid 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Bus Bay 577X Metro Silver Line 8 18 Bus Bay Lower Level Bus Bays Elevator 76 Escalator 17 Bike Rail 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 EMS Bike Parking 270 176 Discharge Only Commuter 770 70 Connection Parking Building 13-0879 ©2012 LACMTA DEC 2012 Subject to Change Destinations Lines Bus Bay or Destinations Lines Bus Bay or Destinations Lines Bus Bay or Street Stop Street Stop Street Stop 7th St/Metro Center Rail Station Metro Silver Line 18 19 Hacienda Heights FT282 16 Pershing Square Metro Rail Station Metro Silver Line , 70, 76, 770, 1 2 17 18 37th St/USC Transitway Station Metro Silver Line 18 19 FT Silver Streak 19 20 21 Harbor Fwy Metro Rail Station Metro Silver Line 18 19 Pomona TransCenter ÅÍ FT Silver Streak 28 Alhambra 76, 176 6 17 Highland Park 176 6 Altadena 267, 268 9 10 Puente Hills Mall FT178, FT282 14 16 Industry Å 194, FT282 13 16 Arcadia 268, -

SATS Final Transit Element Report

PPPINAL CCCOUNTY small area transportation study FINAL Transit Element Report PPPREPARED FFFOROROR ::: PPPINAL CCCOUNTY DDDEVELOPMENT SSSERVICES DDDEPARTMENT OF PPPUBLIC WWWORKS PPPREPARED BBBYYY::: KKKIRKHAM MMMICHAEL CCCONSULTING EEENGINEERS IIININ AAASSOCIATIONASSOCIATION WITH LLLIMA &&& AAASSOCIATES August 2006 KM Project # 0504900 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXISTING TRANSIT CONDITIONS ..............................................................1 1.1 Existing Transit Characteristics ................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Demographics ....................................................................................................................1 1.1.2 Current Mode to Work .......................................................................................................2 1.2 Existing Transit Services ............................................................................................. 2 1.2.1 Coolidge Cotton Express....................................................................................................2 1.2.2 Inter-city Bus Service..........................................................................................................3 1.2.3 Special Needs Transit Services ...........................................................................................4 1.2.4 Amtrak Passenger Rail Service ...........................................................................................4 1.2.5 Regional Airport Shuttle .....................................................................................................7 -

Gold Coast Transit District

Ventura Local Agency Formation Commission Gold Coast Transit District Municipal Service Review Prepared By: Ventura Local Agency Formation Commission 800 S. Victoria Avenue Ventura, CA 93009-1850 Accepted by the Commission on July 15, 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Gold Coast Transit District Profile ........................................................................................................ 3 Growth and Population Projections ................................................................................................... 10 Review of Municipal Services ............................................................................................................. 11 Written Determinations ...................................................................................................................... 13 Appendix A........................................................................................................................................... 17 TABLE OF FIGURES Figure 1: Population and Service Area Table ....................................................................................... 5 Figure 2: Operating Revenues Table .................................................................................................... 8 Figure 3: Operating Expenses Table ..................................................................................................... 9 -

Sunline Transit Agency Board of Directors Agenda for 20 June 2018

SunLine Transit Agency June 20, 2018 12:00 p.m. AGENDA Regular Board of Directors Meeting Board Room 32-505 Harry Oliver Trail Thousand Palms, CA 92276 In compliance with the Brown Act and Government Code Section 54957.5, agenda materials distributed 72 hours prior to the meeting, which are public records relating to open session agenda items, will be available for inspection by members of the public prior to the meeting at SunLine Transit Agency’s Administration Building, 32505 Harry Oliver Trail, Thousand Palms, CA 92276 and on the Agency’s website, sunline.org. In compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, Government Code Section 54954.2, and the Federal Transit Administration Title VI, please contact the Clerk of the Board at (760) 343-3456 if special assistance is needed to participate in a Board meeting, including accessibility and translation services. Notification of at least 48 hours prior to the meeting time will assist staff in assuring reasonable arrangements can be made to provide assistance at the meeting. ITEM RECOMMENDATION 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. ROLL CALL 3. PRESENTATIONS a) Capital Projects Update (Staff: Rudy Le Flore, Chief Project Consultant) b) SunLine University: Talent Development (Staff: Jenny Bellinger, Performance Project Assistant) 4. FINALIZATION OF AGENDA 5. APPROVAL OF MINUTES – APPROVE MAY 23, 2018 BOARD MEETING (PAGE 4-6) SUNLINE TRANSIT AGENCY BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING PAGE 2 JUNE 20, 2018 ITEM RECOMMENDATION 6. PUBLIC COMMENTS RECEIVE COMMENTS NON AGENDA ITEMS Members of the public may address the Board regarding any item within the subject matter jurisdiction of the Board; however, no action may be taken on off-agenda items unless authorized. -

Transit Service Plan

Attachment A 1 Core Network Key spines in the network Highest investment in customer and operations infrastructure 53% of today’s bus riders use one of these top 25 corridors 2 81% of Metro’s bus riders use a Tier 1 or 2 Convenience corridor Network Completes the spontaneous-use network Focuses on network continuity High investment in customer and operations infrastructure 28% of today’s bus riders use one of the 19 Tier 2 corridors 3 Connectivity Network Completes the frequent network Moderate investment in customer and operations infrastructure 4 Community Network Focuses on community travel in areas with lower demand; also includes Expresses Minimal investment in customer and operations infrastructure 5 Full Network The full network complements Muni lines, Metro Rail, & Metrolink services 6 Attachment A NextGen Transit First Service Change Proposals by Line Existing Weekday Frequency Proposed Weekday Frequency Existing Saturday Frequency Proposed Saturday Frequency Existing Sunday Frequency Proposed Sunday Frequency Service Change ProposalLine AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl R2New Line 2: Merge Lines 2 and 302 on Sunset Bl with Line 200 (Alvarado/Hoover): 15 15 15 20 30 60 7.5 12 7.5 15 30 60 12 15 15 20 30 60 12 12 12 15 30 60 20 20 20 30 30 60 12 12 12 15 30 60 •E Ğǁ >ŝŶĞϮǁ ŽƵůĚĨŽůůŽǁ ĞdžŝƐƟŶŐ>ŝŶĞƐϮΘϯϬϮƌŽƵƚĞƐŽŶ^ƵŶƐĞƚůďĞƚǁ -

Transportation & Mobility Element (Policy Maps)

Policy Map TM-1 Roadway Network County Boundary Roadway Designation Community Planning Area Freeway Incorporated City/Town Major Divided Highway Major Roadway w/o Designa tion Major Arterial Highway Major Highway Secondary Highway Controlled/Limited Access Collector Mountain Major Highway Mountain Secondary Highway State Highway (Special Standards or Conditions) Æÿ15 ÿÆ58 ÿÆ40 ÿÆ15 Æÿ395 Æÿ40 ÿÆ247 ÿÆ18 ÿÆ15 ÿÆ18 ÿÆ138 Æÿ247 ÿÆ173 ÿÆ15 ÿÆ138 Æÿ18 ÿÆ215 Æÿ38 Æÿ30 ÿÆ330 Æÿ210 ÿÆ210 Æ Æ Æÿ62 ÿ62 Æÿ15 ÿ66 ÿÆ215 Æ Æÿ10 ÿ83 Æ ÿÆ60 ÿ10 ÿÆ71 Miles 0 4 8 12 16 Date: 7/6/2020 Created by PlaceWorks, Fehr & Peers | Source: County of San Bernardino 2018 G r an d A v e Arrow Hwy Arrow Walnut Walnut vAe Æ ÿ 71 71 Ed sion A e v EdA sion e B u t t e Central Ave r f i e l d R a n c h San An R d d Mt Bal Mountain Ave Heigh 16Th 16Th St Riverside Dr E u d d i c l v e e 8Th 8Th St A ton Æ ÿ 83 83 t dy s Hol Hol io Fourth Fourth St t Blvd MtBa l dy Campus Ave R d 0 ÿÆ 60 Gro ev Ave Mission Blvd Blvd Mission t an Sil 1 nerCa Vineyard Ave 19Th St W 2 il Archibald Ave son Ave Æ ÿ 210 Jurupa Jurupa St 3 Haven Ave Base Lne Rd Valley Valley 4 Milliken A ve i Airport Airport Dr 5 M Æ ÿ Banyan Banyan St iles 15 15 Day Creek Blvd Etiwanda Ave Ly Ly Date:7/6/2020 Mulb rery Ave t l Arrow Arrow Rte e Creek Ch rery Ave Basel Basel uJ S rupa Ave ine Ave H u i m g m Beech Ave h L y t l l i e t C a r n A e Created by PlaceWorks, Fehr & | Peers Source: County of San Bernardino 2018 e d v k R e d Æ ÿ A 10 Va l Va Æ ÿ v Citrus Ave 15 e e l ey ey Blvd Æ ÿ 210 San San Bernard -

Greater Los Aneles Office Q4 2020

M A R K E T B E AT GREATER LOS ANGELES Office Q4 2020 YoY 12-Mo. ECONOMIC OVERVIEW: Slow Recovery, Record Job Losses in 2020 and Vaccine Optimism Chg Forecast Although total nonfarm employment in Los Angeles County increased by 29,800 in November and has since made up 47.6% of the job deficit sustained in March and April, it remained below year-ago levels with every industry sector posting job reductions. With 17.9% the loss of 386,100 jobs in the last year (-8.3%), Los Angeles County’s unemployment rate rose from 4.3% in November 2019 to Vacancy Rate 11.0% in November 2020. Sectors that fuel the demand for office space posted significant declines with the professional and business services contracting by 47,000 jobs, the information sector losing 36,400 jobs and the educational and health services -4.5M sector posting the lost of 37,900 jobs. Net Abs. YTD, SF SUPPLY: Office Inventory Rises at Year-end and Asking Rental Rates Not Indicative of the Market The Greater Los Angeles’ (GLA) current office inventory of 205.9 million square feet (msf) has increased by 2.2 msf from this time last $3.62 year, with 27 office buildings added throughout 2020. There are more than 6.7 msf of new office projects (Under Construction/Under Asking Rent, PSF Renovation) still under way, LA Central and LA West lead the market with 2.0 msf and 2.9 msf respectively. While demand remains (Overall psf/mo, All PropertyClasses) uncertain in the near future and more available space hits the market, it is expected that most new developments would be on hold until later in 2021. -

Land Use Element Designates the General Distribution and Location Patterns of Such Uses As Housing, Business, Industry, and Open Space

CIRCULATION ELEMENT CITY OF HAWTHORNE GENERAL PLAN Adopted April, 1990 Prepared by: Cotton/Beland/Associates, Inc. 1028 North Lake Avenue, Suite 107 Pasadena, California 91104 Revision Table Date Case # Resolution # 07/23/2001 2001GP01 6675 06/28/2005 2005GP03 & 04 6967 12/09/2008 2008GP03 7221 06/26/2012 2012GP01 7466 12/04/2015 2015GP02 7751 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page I. Introduction to the Circulation Element 1 Purpose of this Element 1 Relation to Other General Plan Elements 1 II. Existing Conditions 2 Freeways 2 Local Vehicular Circulation and Street Classification 3 Transit Systems 4 Para-transit Systems 6 Transportation System Management 6 TSM Strategies 7 Non-motorized Circulation 7 Other Circulation Related Topics 8 III. Issues and Opportunities 10 IV. Circulation Element Goals and Policies 11 V. Crenshaw Station Active Transportation Plan 23 Circulation Element March 1989 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page Figure1: Street Classification 17 Figure 2: Traffic Volume Map 18 Figure 3: Roadway Standards 19 Figure 4: Truck Routes 20 Figure 5: Level of Service 21 LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Definitions of Level-of-Service 22 Circulation Element March 1989 SECTION I - INTRODUCTION TO THE CIRCULATION ELEMENT Circulation and transportation systems are one of the most important of all urban systems in determining the overall structure and form of the areas they service. The basic purpose of a transportation network within the City of Hawthorne is the provision of an efficient, safe, and serviceable framework which enables people to move among various sections of the city in order to work, shop, or spend leisure hours. -

The Transit Advocate

How to join SO.CA.TA: Yearly dues are $30.00 cates. In all other cases, permission must be ($12.00 low income). Dues are prorated on a secured from the copyright holder. quarterly basis. Disclaimer: The Southern California Transit THE TRANSIT ADVOCATE Submission of materials: ALL materials for the Advocates is not affiliated with any governmental TRANSIT ADVOCATE newsletter go to Andrew agency or transportation provider. Names and Newsletter of the Southern California Transit Advocates Novak at P.O. Box 2383, Downey California 90242 logos of agencies appear for information and or to [email protected]. Please enclose a self reference purposes only. November 2011 Vol. 19, No. 11 ISSN 1525-2892 addressed stamped envelope for returns. SO.CA.TA officers, 2011 Newsletter deadlines are the Fridays a week President: Nate Zablen before SO.CA.TA meetings, at 6:00 p.m. Pacific Vice President: Kent Landfield time, unless otherwise announced. Recording Secretary: Edmund Buckley Executive Secretary: Dana Gabbard Opinions: Unless clearly marked as "Editorial" or Treasurer: Dave Snowden "Position Paper", all written material within, Directors at Large: Ken Ruben including all inserted flyers and postcards, are the J.K. Drummond expressed opinions of the authors and not Joe Dunn necessarily that of the Southern California Transit ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Advocates. Newsletter Editor: Andrew Novak Newsletter Prod. Mgr: Dana Gabbard Copyright: © 2011 Southern California Transit Webmaster: Charles Hobbs Advocates. Permission is freely granted to repro-