A Visual Journey Into the Bible the Book of Genesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creativity Over Time and Space

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Serafinelli, Michel; Tabellini, Guido Working Paper Creativity over Time and Space IZA Discussion Papers, No. 12644 Provided in Cooperation with: IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Suggested Citation: Serafinelli, Michel; Tabellini, Guido (2019) : Creativity over Time and Space, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 12644, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), Bonn This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/207469 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12644 Creativity over Time and Space Michel Serafinelli Guido Tabellini SEPTEMBER 2019 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12644 Creativity over Time and Space Michel Serafinelli University of Essex, IZA and CReAM Guido Tabellini IGIER, Università Bocconi, CEPR, CESifo and CIFAR SEPTEMBER 2019 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. -

ARTIST Is in Caps and Min of 6 Spaces from the Top to Fit in Before

PAUL BRIL (Antwerp c. 1554 – 1626 Rome) A Landscape with a Hunting Party and Roman Ruins On canvas, 27¾ x 38 ¾ ins. (70.5 x 98.4 cm) Provenance: The Duke of Sutherland, Dunrobin Castle, by 1921 By whom sold, Christie’s, London, 29 November 1957, lot 31 Where purchased by Thos. Agnew & Sons, London Denys Sutton (1917-1991), London Thence by descent to the previous owner Exhibited: Thos. Agnew & Sons Ltd., London, 1958 Ideal & Classical Landscape, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, 6 February – 3 April 1960, cat. no. 18 L’Ideale classico del Seicento in Italia e la pittura di paesaggio, Bologna, 8 September – 11 November, 1962, cat. no. 124 Literature: The Duke of Sutherland, Dunrobin Castle Catalogue, 1921, no. 253 Art News, April 1958, vol. 57, no. 2, p. 4 (reproduced) F. Cappelletti, Paul Bril, et la pittura di paesaggio a Roma 1580- 1630, Rome, 2005, p. 304, cat. no. 166 (reproduced) Note: We are grateful to Drs. Luuk Pijl for confirming the attribution to Bril, based on photographs. Drs. Pijl dates the work to between 1617-1620 and will include it in his forthcoming catalogue raisonné of Paul Bril’s paintings. VP4601 Paul Bril trained in Antwerp before making his way to Italy sometime before 1582. In Rome, he joined his older brother Matthijs (c. 1550-83), who was already established in the employment of Pope Gregory XIII, producing fresco decorations for the Vatican. Initially, Paul assisted his brother, but after Matthijs’s premature death in 1583, he assumed responsibility for the papal commissions both in the Vatican and in various churches and villas in and around Rome. -

The Unification of Violence and Knowledge in Cornelis Van Haarlem’S Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon

History of Art MA Dissertation, 2017 Ruptured Wisdom: The Unification of Violence and Knowledge in Cornelis van Haarlem’s Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon Cornelis van Haarlem, Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon, 1588 History of Art MA – University College London HART G099 Dissertation September 2017 Supervisor: Allison Stielau Word Count: 13,999 Candidate Number: QBNB8 1 History of Art MA Dissertation, 2017 Ruptured Wisdom: The Unification of Violence and Knowledge in Cornelis van Haarlem’s Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon Striding into the wood, he encountered a welter of corpses, above them the huge-backed monster gloating in grisly triumph, tongue bedabbled with blood as he lapped at their pitiful wounds. -Ovid, Metamorphoses, III: 55-57 Introduction The visual impact of the painting Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon (figs.1&2), is simultaneously disturbing and alluring. Languidly biting into a face, the dragon stares out of the canvas fixing the viewer in its gaze, as its unfortunate victim fails to push it away, hand resting on its neck, raised arm slackened into a gentle curve, the parody of an embrace as his fight seeps away with his life. A second victim lies on top of the first, this time fixed in place by claws dug deeply into the thigh and torso causing the skin to corrugate, subcutaneous tissue exposed as blood begins to trickle down pale flesh. Situated at right angles to each other, there is no opportunity for these bodies to be fused into a single cohesive entity despite one ending where the other begins. -

HNA April 11 Cover-Final.Indd

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 28, No. 1 April 2011 Jacob Cats (1741-1799), Summer Landscape, pen and brown ink and wash, 270-359 mm. Hamburger Kunsthalle. Photo: Christoph Irrgang Exhibited in “Bruegel, Rembrandt & Co. Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850”, June 17 – September 11, 2011, on the occasion of the publication of Annemarie Stefes, Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850, Kupferstichkabinett der Hamburger Kunsthalle (see under New Titles) HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone/Fax: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Board Members Contents Dagmar Eichberger (2008–2012) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009–2013) Matt Kavaler (2008–2012) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010–2014) Exhibitions -

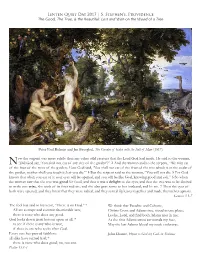

Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel, the Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man (1617)

Lenten Quiet Day 2017 | S. Stephen’s, Providence The Good, The True, & the Beautiful: Lost and Won on the Wood of a Tree Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel, The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man (1617) ow the serpent was more subtle than any other wild creature that the Lord God had made. He said to the woman, N“Did God say, ‘You shall not eat of any tree of the garden’?” 2 And the woman said to the serpent, “We may eat of the fruit of the trees of the garden; 3 but God said, ‘You shall not eat of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden, neither shall you touch it, lest you die.’” 4 But the serpent said to the woman, “You will not die. 5 For God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” 6 So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate; and she also gave some to her husband, and he ate. 7 Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made themselves aprons. Genesis 3.1-7 The fool has said in his heart, “There is no God.” * We think that Paradise and Calvarie, All are corrupt and commit abominable acts; Christs Cross and Adams tree, stood in one place; there is none who does any good. -

1 Curriculum Vitae Prof. Dr. Ron Spronk

Curriculum Vitae Prof. dr. Ron Spronk Professor of Art History Department of Art History and Art Conservation Ontario Hall, Room 315 67 University Avenue Kingston, Ontario Canada K7L 3N6 SNS Reaal Fund Hieronymus Bosch Chair (20% FTE) Radboud University Nijmegen The Netherlands T: 613 533-6000, extension 78288 F: 613 533-6891 E: [email protected] Degrees: Ph.D., Groningen University, the Netherlands, Department of History of Art and Architecture, 2005. Doctoral Candidacy, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA, Art History Department, 1994. Master’s degree equivalent (Dutch Doctoraal Diploma), Groningen University, the Netherlands, Department of History of Art and Architecture, 1993. Employment history: Since 2010: Hieronymus Bosch Chair, Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands (20% FTE). Since 2007: Professor of Art History (tenured), Department of Art, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Department Head from 2007 to 2010. 2006-2007: Research Curator, Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard University Art Museums, Cambridge MA, USA. 2005-2007: Lecturer on History of Art and Architecture, Department of History of Art and Architecture, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. 1999-2006: Associate Curator for Research, Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard University Art Museums, Cambridge MA, USA. 2004: Lecturer, Department of History of Art and Architecture, Groningen University, the Netherlands. 1997-1999: Research Associate for Technical Studies, Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard University Art Museums, Cambridge MA, USA. 1996-1997: Andrew W. Mellon Research Fellow, Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard University Art Museums, Cambridge MA, USA. 1995-1996: Special Conservation Intern, Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard University Art Museums, Cambridge MA, USA. -

The Collecting, Dealing and Patronage Practices of Gaspare Roomer

ART AND BUSINESS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NAPLES: THE COLLECTING, DEALING AND PATRONAGE PRACTICES OF GASPARE ROOMER by Chantelle Lepine-Cercone A thesis submitted to the Department of Art History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (November, 2014) Copyright ©Chantelle Lepine-Cercone, 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the cultural influence of the seventeenth-century Flemish merchant Gaspare Roomer, who lived in Naples from 1616 until 1674. Specifically, it explores his art dealing, collecting and patronage activities, which exerted a notable influence on Neapolitan society. Using bank documents, letters, artist biographies and guidebooks, Roomer’s practices as an art dealer are studied and his importance as a major figure in the artistic exchange between Northern and Sourthern Europe is elucidated. His collection is primarily reconstructed using inventories, wills and artist biographies. Through this examination, Roomer emerges as one of Naples’ most prominent collectors of landscapes, still lifes and battle scenes, in addition to being a sophisticated collector of history paintings. The merchant’s relationship to the Spanish viceregal government of Naples is also discussed, as are his contributions to charity. Giving paintings to notable individuals and large donations to religious institutions were another way in which Roomer exacted influence. This study of Roomer’s cultural importance is comprehensive, exploring both Northern and Southern European sources. Through extensive use of primary source material, the full extent of Roomer’s art dealing, collecting and patronage practices are thoroughly examined. ii Acknowledgements I am deeply thankful to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Sebastian Schütze. -

Defining De Backer New Evidence on the Last Phase of Antwerp Mannerism Before Rubens

Originalveröffentlichung in: Gazette des beaux-arts 6. Pér., 137, 143. année (2001), S. 167-192 DEFINING DE BACKER NEW EVIDENCE ON THE LAST PHASE OF ANTWERP MANNERISM BEFORE RUBENS BY ECKHARD LEUSCHNER VEN Carel van Mander, though praising has became an art-collector's synonym for a the great talent of the late 16th-century certain type of 'elegant' paintings made by the last painter Jacob ('Jacques') de Backer, knew generation of Antwerp artists before Rubens, just little about this Antwerp-based artist and as 'Jan Brueghel' once was a synonym for early E 1 the scope of his activities . It is, therefore, not 17th-century Antwerp landscapes. Yet, while many surprising to find De Backer's pictures cited in efforts have been made in recent years to comparatively few Antwerp art inventories of the constitute a corpus of Jan Brueghel's paintings and 17th and 18th centuries2. The provenance of only a drawings, the art of Jacob de Backer remains to be handful of the paintings today attributed to Jacob explored. de Backer can be documented. The artist's name, Scholarly approaches to De Backer have so far moreover, never features in the membership lists been limited to efforts at a traditional ceuvre ('liggeren') of Antwerp's guild of painters. The art catalogue3. Miiller Hofstede, Huet, Foucart, and market, however, does not appear to be impressed everyone else following them (the author of this by this fact: The name of De Backer is regularly paper included) tried to create or enlarge a corpus applied to late 16th-century Flemish pictures with of works of art produced by a distinct personality marble-like figures reminiscent of the Florentine called Jacob de Backer. -

And Where He Did

Vol. 2 No. 9 October 1992 $4.00 and where he did Volume 2 Number 9 I:URI:-KA STRI:-eT October 1992 A m agazine of public affairs, the arts and theology 21 CoNTENTS TOPGUN Michael McGirr reports on gun laws and the calls for capital punishment in the 4 Philippines. COMMENT In this year of elections we are only as good 22 as our choices, says Peter Steele. Andrew DON'T KISS ME, HARDY Hamilton looks at the Columbus quin James Griffin concludes his series on the centary, and decides that the past must be Wren-Evatt letters. owned as well as owned up to (pS). 6 25 ORIENTATIONS LETTERS Peter Pierce and Robin Gerster take their pens to Shanghai and Saigon; Emmanuel 7 Santos and Hwa Goh take their cameras to COMMISSIONS AND OMISSIONS Tianjin. ICAC chief Ian Temby Margaret Simons talks to Australia's top speaks for himself: p 7 crime-busters. 34 11 BOOKS AND ARTS Cover photo: A member of Was the oldest part of the Pentateuch CAPITAL LETTER the Tianjing city planning office written by a woman? Kevin Hart reviews in Jei Fang Bei Road, three books by Harold Bloom, who thinks the 'Wall Street' of Tianjin. 12 it was; Robert Murray sizes up Columbus BLINDED BY THE LIGHT and colonialism (p38 ). Cover photo and photos pp25, 29 and 30 Bruce Williams visits the Columbus light by Emmanuel Santos; house in Santo Domingo, and wonders who Photo p27 by Hwa Goh; will be enlightened. 40 Photos p12 by Belinda Bain; FLASH IN THE PAN Photo p41 by Bill Thomas; 15 Reviews of the films Patriot Games Cartoons pp6, 36 and 3 7 by Dean Moore; Zentropa, Edward II, and Deadly. -

Simonetta Prosperi Valenti Rodinò

©Ministero per beni e le attività culturali-Bollettino d'Arte SIMONETTA PROSPERI VALENTI RODINÒ IL CARDINAL GIUSEPPE RENATO IMPERIALI COMMITTENTE E COLLEZIONISTA I. - LE COMMITTENZE ARTISTICHE Il gusto art1st1co e il mecenatismo si erano mani Dopo essere stata la capitale europea dell'arte con festati anche in altri esponenti della famiglia, di anti i Barberini, i Pamphilj e i Chigi, Roma vive alla fine chissima origine genovese, che con l'acquisto di feudi del XVII secolo un lento declino legato alle vicende -Oria e Francavilla in terra d'Otranto e Sant'Angelo politiche, che la porta a cedere il suo primato alla dei Lombardi nell'Avellinese - a cavallo tra il XVI Francia; mentre l'Inghilterra e le corti nascenti della e il XVII secolo, iniziò gradualmente a gravitare sul Regno di Napoli,4l Particolarmente importante nella Germania consolidano o iniziano una politica di acqui sti di opere d'arte per le gallerie che si vanno creando. storia del collezionismo era stato Gian Vincenzo, Roma conserva un ruolo importante come capitale ammiraglio della flotta genovese, uomo politico e del mondo classico, ma non si caratterizza più come letterato: i più bei pezzi della sua quadreria, tra cui centro propulsore di movimenti artistici, quale era Tiziano, Rubens, Veronese, Correggio, passarono nel stata con il Bernini, il Borromini e Pietro da Cortona. 1667 da Genova a Roma nella collezione di Cristina Si assiste peraltro, tra la fine del Sei e l'inizio del di Svezia.s> Settecento, al proliferare di committenze "minori " di cardinali nelle chiese del loro titolo ed al formarsi di numerose quadrerie in palazzi nobiliari, che con sentono di ricostruire il complesso panorama artistico romano di quegli anni.1> Pur essendo ancora molto ambite le committenze pontificie, furono piuttosto i collezionisti - quali il marchese Niccolò Pallavicini, i cardinali Alessandro Albani, Pietro Ottoboni, Neri Corsini, Silvio Valenti Gonzaga, per citare solo i più importanti 2 > - a deter minare il diffondersi di un gusto o l'affermarsi di un pittore loro protetto. -

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka 3930424 March 2018 Master Thesis Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context University of Utrecht Prof. dr. M.A. Weststeijn Prof. dr. E. Manikowska 1 Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Index Introduction p. 4 Historiography and research motivation p. 4 Theoretical framework p. 12 Research question p. 15 Chapters summary and methodology p. 15 1. The collection of Stanisław August 1.1. Introduction p. 18 1.1.1. Catalogues p. 19 1.1.2. Residences p. 22 1.2. Netherlandish painting in the collection in general p. 26 1.2.1. General remarks p. 26 1.2.2. Genres p. 28 1.2.3. Netherlandish painting in the collection per stylistic schools p. 30 1.2.3.1. The circle of Rubens and Van Dyck p. 30 1.2.3.2. The circle of Rembrandt p. 33 1.2.3.3. Italianate landscapists p. 41 1.2.3.4. Fijnschilders p. 44 1.2.3.5. Other Netherlandish artists p. 47 1.3. Other painting schools in the collection p. 52 1.3.1. Paintings by court painters in Warsaw p. 52 1.3.2. Italian paintings p. 53 1.3.3. French paintings p. 54 1.3.4. German paintings p. -

South Netherlandish School

southern netherlandish school c.1500 The Virgin and Child oil on panel (arched top) 49.2 x 34.2 cm (19⅜ x 13½ in) HIS DEPICTION OF THE VIRGIN AND CHILD WAS a popular composition in Netherlandish painting during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, but this version stands slightly apart for several reason, not least its exceptional quality. The Virgin gently cradles the infant tChrist in both hands and stares serenely and maternally at Him. She is depicted as Queen of Heaven, dressed in a luxurious pink cloak over a fine tunic and delicate lace veil. She wears a jewelled headband, stands against a richly coloured hanging, and the wall behind her has been inscribed with detailed patterning. Beyond this wall is an extensive landscape dotted with copses of trees, and the whole composition is framed by a decorative foliate arch. The painting is exquisitely painted, with the attention to detail that characterises the best work of the so-called Flemish Primitives. The modelling of light is superb, as it picks out the hollow of the Virgin’s throat, highlights the sculptural folds of her cloak, and shimmers through both figures’ hair. Details such as the slight flush of the Virgin’s cheeks are typical of the overall subtlety of execution. The long slender fingers and rigid postures are also common features of southern Netherlandish painting of this period. As previously mentioned, the composition of the present work was a popular one during this period. Max Friedländer believed it ultimately originated from Rogier van der Weyden’s depiction of the Virgin and Child in his Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin (fig.