On the Record Reporting (512) 450-0342 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brooklyn Law Notes| the MAGAZINE of BROOKLYN LAW SCHOOL SPRING 2018

Brooklyn Law Notes| THE MAGAZINE OF BROOKLYN LAW SCHOOL SPRING 2018 Big Deals Graduates at the forefront of the booming M&A business SUPPORT THE ANNUAL FUND YOUR CONTRIBUTIONS HELP US • Strengthen scholarships and financial aid programs • Support student organizations • Expand our faculty and support their nationally recognized scholarship • Maintain our facilities • Plan for the future of the Law School Support the Annual Fund by making a gift TODAY Visit brooklaw.edu/give or call Kamille James at 718-780-7505 Dean’s Message Preparing the Next Generation of Lawyers ROSPECTIVE STUDENTS OFTEN ask about could potentially the best subject areas to focus on to prepare for qualify you for law school. My answer is that it matters less what several careers.” you study than how you study. To be successful, it Boyd is right. We is useful to study something that you love and dig made this modest Pdeep in a field that best fits your interests and talents. Abraham change in our own Lincoln, perhaps America’s most famous and respected lawyer, admissions process advised aspiring lawyers: “If you are resolutely determined to encourage to make a lawyer of yourself, the thing is more than half done highly qualified students from diverse academic and work already…. Get the books, and read and study them till you backgrounds to apply and pursue a law degree. Our Law understand them in their principal features; and that is the School long has attracted students who come to us with deep main thing.” experience and study in myriad fields. Currently, more than Today, with so much information and knowledge available 60 percent of our applicants have one to five years of work in cyberspace, Lincoln’s advice is more relevant than ever. -

REPORT Donations Are Fully Tax-Deductible

SUPPORT THE NYCLU JOIN AND BECOME A CARD-CARRYING MEMBER Basic individual membership is only $20 per year, joint membership NEW YORK is $35. NYCLU membership automatically extends to the national CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION American Civil Liberties Union and to your local chapter. Membership is not tax-deductible and supports our legal, legislative, lobbying, educational and community organizing efforts. ANNUAL MAKE A TAX-DEDUCTIBLE GIFT Because the NYCLU Foundation is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, REPORT donations are fully tax-deductible. The NYCLU Foundation supports litigation, advocacy and public education but does not fund legislative lobbying, which cannot be supported by tax-deductible funds. BECOME AN NYCLU ACTIVIST 2013 NYCLU activists organize coalitions, lobby elected officials, protest civil liberties violations and participate in web-based action campaigns THE DESILVER SOCIETY Named for Albert DeSilver, one of the founders of the ACLU, the DeSilver Society supports the organization through bequests, retirement plans, beneficiary designations or other legacy gifts. This special group of supporters helps secure civil liberties for future generations. THE AMICUS CLUB Lawyers and legal professionals are invited to join our Amicus Club with a donation equal to the value of one to four billable hours. Club events offer members the opportunity to network, stay informed of legal developments in the field of civil liberties and earn CLE credits. THE EASTMAN SOCIETY Named for the ACLU’s co-founder, Crystal Eastman, the Eastman Society honors and recognizes those patrons who make an annual gift of $5,000 or more. Society members receive a variety of benefits. Go to www.nyclu.org to sign up and stand up for civil liberties. -

Harvard Kennedy School Journal of Hispanic Policy a Harvard Kennedy School Student Publication

Harvard Kennedy School Journal of Hispanic Policy A Harvard Kennedy School Student Publication Volume 30 Staff Kristell Millán Editor-in-Chief Estivaliz Castro Senior Editor Alberto I. Rincon Executive Director Bryan Cortes Senior Editor Leticia Rojas Managing Editor, Print Jazmine Garcia Delgadillo Senior Amanda R. Matos Managing Editor, Editor Digital Daniel Gonzalez Senior Editor Camilo Caballero Director, Jessica Mitchell-McCollough Senior Communications Editor Rocio Tua Director, Alumni & Board Noah Toledo Senior Editor Relations Max Wynn Senior Editor Sara Agate Senior Editor Martha Foley Publisher Elizabeth Castro Senior Editor Richard Parker Faculty Advisor Recognition of Former Editors A special thank you to the former editors Alex Rodriguez, 1995–96 of the Harvard Kennedy School Journal of Irma Muñoz, 1996–97 Hispanic Policy, previously known as the Myrna Pérez, 1996–97 Harvard Journal of Hispanic Policy, whose Eraina Ortega, 1998–99 legacy continues to be a source of inspira- Nereyda Salinas, 1998–99 tion for Latina/o students Harvard-wide. Raúl Ruiz, 1999–2000 Maurilio León, 1999–2000 Henry A.J. Ramos, Founding Editor, Sandra M. Gallardo, 2000–01 1984–86 Luis S. Hernandez Jr., 2000–01 Marlene M. Morales, 1986–87 Karen Hakime Bhatia, 2001–02 Adolph P. Falcón, 1986–87 Héctor G. Bladuell, 2001–02 Kimura Flores, 1987–88 Jimmy Gomez, 2002–03 Luis J. Martinez, 1988–89 Elena Chávez, 2003–04 Genoveva L. Arellano, 1989–90 Adrian J. Rodríguez, 2004–05 David Moguel, 1989–90 Edgar A. Morales, 2005–06 Carlo E. Porcelli, 1990–91 Maria C. Alvarado, 2006–07 Laura F. Sainz, 1990–91 Tomás J. García, 2007–08 Diana Tisnado, 1991–92 Emerita F. -

February 20, 2018 by USPS Express Mail the Honorable Wilbur L. Ross, Jr. Secretary of Commerce U.S. Department of Commerce 1401

131 West 33rd Street Suite 610 New York, NY 10001 (212) 627-2227 www.nyic.org February 20, 2018 By USPS Express Mail The Honorable Wilbur L. Ross, Jr. Secretary of Commerce U.S. Department of Commerce 1401 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20230 John M. Mulvaney Director of the Office of Management and Budget 725 17th Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20503 Dear Secretary Ross and Director Mulvaney: On behalf of 106 undersigned organizations throughout New York State, we are requesting that you reject any effort by the Department of Justice to add a question regarding citizenship to the 2020 decennial Census. To do otherwise, would severely undermine the accuracy and non- partisan legitimacy of the Census, impair the delicate trust between the community and the role of the Census, and skyrocket the cost of the Census. A non-partisan, reliable and responsive 2020 Census is needed to ensure the proper distribution of over $600 billion in federal funding to communities across this country for needed schools, hospitals, housing, and transportation. For that reason, great effort has been expended by the Census to ensure questions will elicit both an accurate and high response rate, a process that has involved extensive screening, focus groups, and field tests. At this stage in the process, there is no time to add questions that have not been properly vetted, especially since citizenship is already included in the American Community Survey. There is no doubt that adding a citizenship question to the decennial Census would pose a chilling effect and result in a significant undercount, particularly by already under-counted racial and ethnic minority groups, including immigrants and non-citizens. -

EXHIBIT 4 Case 1:18-Cv-11657-ER Document 48-4 Filed 01/17/19 Page 2 of 32

Case 1:18-cv-11657-ER Document 48-4 Filed 01/17/19 Page 1 of 32 EXHIBIT 4 Case 1:18-cv-11657-ER Document 48-4 Filed 01/17/19 Page 2 of 32 New York Office Office for Civil Rights U.S. Department of Education 32 Old Slip, 26th Floor New York, NY 10005-2500 September 27,2012 RE The admissions process for New York City's elite public high schools violates Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and its implementing regulations Dear New York Office Each year, nearly 30,000 eighth and ninth graders compete for the chance to attend Stuyvesant High School (Stuyvesant), The Bronx High School of Science (Bronx Science), Brooklyn Technical High School (Brooklyn Tech), and five other public high schools that are among the best schools in New York City and, indeed, the nation. Known as the "Specialized High Schools," these eight prestigious institurtions are operated by the New York City Departrnent of Education (NYCDOE). They provide a pathway to opportunity for their graduates, rnany of whom go on to attend the country's best colleges and universities, and become leaders in our nation's economic, political, and civic life. For decades, a single factor has been used to determine access to these Specialized High Schools-a student's rank-order score on a2.5 hour multiple choice test called the Specialized High School Adrnissions Test (SHSAT). Undel this admissions policy, regardless of whether a student has achieved straight A's from kindergarten through eighth grade or whether he or slre demonstrates other signs of high academic potential, the only factor that matters for admission is his or her score on a single test. -

New Yorkers for Responsible Lending

NEW YORKERS FOR RESPONSIBLE LENDING NYRL Members AARP Abyssinian Development Corp. Affordable Housing Partnership AFSCME New York Albany County Rural Housing Alliance Albany Housing Coalition Alternatives FCU American Debt Resources, Inc. Anti-Discrimination Center Arbor Housing and Development Asian Americans for Equality Assoc. for Neighborhood & Housing Development Belmont Housing Resources for Western New York Better Community Neighborhoods, Inc. Bridge Street Development Corp. Bronx Legal Services Brooklyn Branch NAACP Brooklyn Cooperative FCU Brooklyn Legal Services Brooklyn Legal Services Corp. A Brooklyn Neighborhood Services Brooklyn-Wide Interagency Council of the Aging Buffalo Urban League Business Outreach Center Network, Inc. CAMBA Catholic Charities, Brooklyn and Queens Center for Elder Law & Justice Center for NYC Neighborhoods Central NY Citizens in Action Chhaya CDC Children’s Defense Fund - NY Citizen Action of NY CNY Fair Housing Common Cause NY Community Action in Self-Help CDC of Long Island Community Homeowners & Neighborhoods Gaining Economic Rights Community Housing Innovations Community Loan Fund of the Capital Region Community Service Society of New York Consumer Credit Counseling Service of Rochester Consumer Reports Cooper Square Committee Cooperative Federal Cultural Renaissance for Economic Revitalization Cypress Hills Local Development Corp. Dēmos District Council 1707, AFSCME District Council 37, AFSCME Drum Major Institute Ellicott District Community Development Empire Justice Center Enterprise Community -

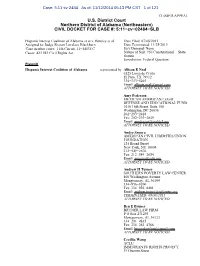

DOCKET for CASE #: 5:11−Cv−02484−SLB

Case: 5:11-cv-2484 As of: 11/12/2014 05:13 PM CST 1 of 121 CLOSED,APPEAL U.S. District Court Northern District of Alabama (Northeastern) CIVIL DOCKET FOR CASE #: 5:11−cv−02484−SLB Hispanic Interest Coalition of Alabama et al v. Bentley et al Date Filed: 07/08/2011 Assigned to: Judge Sharon Lovelace Blackburn Date Terminated: 11/25/2013 Case in other court: 11th Circuit, 11−14535 C Jury Demand: None Cause: 42:1983 Civil Rights Act Nature of Suit: 950 Constitutional − State Statute Jurisdiction: Federal Question Plaintiff Hispanic Interest Coalition of Alabama represented by Allison E Neal 6525 Loma de Cristo El Paso, TX 79912 334−333−5203 Email: [email protected] ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Amy Pedersen MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND 1016 16th Street, Suite 100 Washington, DC 20036 202−293−2828 Fax: 202−293−2849 Email: [email protected] ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Andre Segura AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION 125 Broad Street New York, NY 10004 212−549−2676 Fax: 212−549−2654 Email: [email protected] ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Andrew H Turner SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER 400 Washington Avenue Mongtomery, AL 36104 334−956−8200 Fax: 334−956−8481 Email: [email protected] TERMINATED: 09/30/2011 ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Ben E Bruner BRUNER LAW FIRM P O Box 231293 Montgomery, AL 36123 334−201−0835 Fax: 334−263−4766 Email: [email protected] ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Cecillia Wang ACLU IMMIGRANTS' RIGHTS PROJECT 39 Drumm Street Case: 5:11-cv-2484 As of: 11/12/2014 05:13 PM CST 2 of 121 San Francisco, CA 94111 415−343−0775 -

Diverse Coalition of Student and Community Organizations

Diverse Coalition of Student and Community Organizations Permitted to Intervene in Suit to Defend Expanded Access for Black and Latinx Students to New York City’s Specialized High Schools In a recent decision, Teens Take Charge – a public school student-led organization, the Hispanic Federation, Desis Rising Up & Moving (DRUM), the Coalition for Asian American Children and Families (CACF), and multiple Black and Latinx public school students and their families were granted intervenor status in Christa McAuliffe Intermediate School PTO v. Bill de Blasio, a lawsuit filed by the Pacific Legal Foundation, a conservative California-based organization, on behalf of individuals and organizations aiming to halt New York City’s attempts to make its Specialized High Schools more inclusive and representative of the City’s overall student population. The motion for intervenor status was filed last spring by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF), LatinoJustice PRLDEF, New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU), and American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to ask the Court to allow these organizations and the families they represent to defend the modest steps the City has taken to increase access for disadvantaged students and rectify the exclusion of Black, Latinx and certain AAPI students caused by the test-only admissions policy. “The voices of Black, Latinx, and underrepresented Asian Pacific American students must be front and center in any discussion of systemic racial inequity in New York City’s Specialized High Schools,” said Rachel Kleinman, Senior Counsel at LDF. “The students and families we represent will now be able to make the case for educational equity in a court of law, as well as in the halls of government and the streets of New York City, where they have been pushing for much-needed reform. -

President and General Counsel ANNOUNCEMENT Latinojustice PRLDEF Is Launching a Nationwide Searc

Executive Search Announcement: President and General Counsel ANNOUNCEMENT LatinoJustice PRLDEF is launching a nationwide search for the position of President and General Counsel. Interested candidates should submit a resume and cover letter to the following email address: [email protected]. No phone calls please. SUMMARY Job Title: President and General Counsel. Organization: LatinoJustice PRLDEF. Founded in 1972, LatinoJustice PRLDEF is one of the nation’s preeminent civil rights and education organizations. More information about the organization, its history, and its work can be found at www.latinojustice.org and in the back sections of this announcement. Location: New York City. Compensation: Competitive. Benefits: Comprehensive medical and dental. 401(k) retirement savings plan. Relocation: No relocation package will be offered, but candidates outside of New York City are encouraged to apply. Experience: 8+ years of direct litigation involvement, with experience in the area of civil rights, and a demonstrated interest in and commitment to the Latino community. Admitted to New York Bar or eligible for admission. POSITION DESCRIPTION The President and General Counsel is the chief executive officer of LatinoJustice PRLDEF and will report to and work in partnership with the board of directors to further the mission, goals and objectives of the organization. S/he should have a demonstrated commitment to the struggle for economic, political and social justice for the Latino community, excellent strategic judgment, strong management skills, a compelling public presence, and the ability to raise funds from corporations, foundations and major donors. This position offers an opportunity to assume the leadership of one of the most important organizations protecting civil rights in the Latino community. -

Press Release

THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK ***For Immediate Release*** October 22, 2014, 11:30am Contact: Benjamin Smith [Lander] 212-788-6969, [email protected] Rahul Saksena [Torres] 212-788-6966, [email protected] M. Ndigo Washington [Barron] 212-788-6957 [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ New York City Council Members aim to confront segregation and increase diversity in NYC schools Trio of bills would call on DOE to prioritize, plan for, and measure progress toward more diverse schools. Resolution also joins Mayor, NAACP and others to call for changes to specialized high school admissions. October 22, 2014 (NYC) – New York City Council Members stood with parents, educators, and civil rights advocates on Wednesday in support of policies to confront segregation and increase diversity in NYC public schools. Citing research that New York’s schools are amongst the most segregated in the nation, Council Members announced legislation to prioritize, plan for, and measure progress toward diversity in the city’s schools. Advocates also discussed innovative efforts to boost diversity at the school and district levels. Diversity is one of NYC’s greatest strength. Evidence shows that students benefit from learning in settings with students from many different backgrounds. Unfortunately, 60 years after the Supreme Court rules in Brown v. Board of Education, that “separate but equal is inherently unequal,” New York's schools are amongst the most segregated in the nation, according to a study earlier this year by The Civil Rights Project at UCLA.1 Residential segregation, test-based admissions, and “choice” admissions processes that fail to prioritize diversity continue to take our schools in the wrong direction. -

“DELIBERATE INDIFFERENCE”: an NYPD for All New Yorkers

BEYOND “DELIBERATE INDIFFERENCE”: An NYPD for All New Yorkers New York Civil Liberties Union 125 Broad Street, 19th Floor New York, NY 10004 I www.nyclu.org Published November 2013 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was written by Johanna Miller, Udi Ofer, Mike Cummings, Candis Tolliver, Jen Carnig, Beth Haroules and Sara LaPlante. It was edited by Johanna Miller, Chris Dunn, Donna Lieberman, Jen Carnig, Art Eisenberg, Mike Cummings and Helen Zelon. It was designed by Abby Allender. Sara LaPlante provided data analysis and created graphics. The New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) is one of the nation’s foremost defenders of civil liberties and civil rights. Founded in 1951 as the New York affiliate of the American Civil Liberties Union, we are a not-for-profit, nonpartisan organization with eight chapters and national offices, and 50,000 supporters across the state. Our mission is to defend and promote the fundamental principles and values embodied in the Bill of Rights, the U.S. Constitution and the New York Constitution, including freedom of speech and religion, and the right to privacy, equality and due process of law for all New Yorkers. NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION 125 Broad Street, 19th floor New York, NY 10004 www.nyclu.org INTRODUCTION Dear Reader, On Mayor Bloomberg’s watch, policing has dangerously encroached into the lives of everyday New Yorkers. In communities of color across the city, walking to work, the subway or the corner store can result in an unjustified, humiliating and frightening stop-and-frisk encounter – a wholesale practice of discrimination and racial profiling denounced as unconstitutional by Judge Shira Scheindlin in August, 2013. -

2020 Sorensen Fellows

2020 FELLOWS MAKE IMPACT IN NEW YORK CITY AND AROUND THE WORLD Sarah Axtell - Legal Aid Society (Health Law) Jackie Bonilla - Make the Road NY Jeremy Chan-Kraushar - Race, Law, and Public Education project Nishat Choudhury - NYS Housing and Community Renewal (Fair and Equitable Housing) Simone Harstead - Kids in Need of Defense (KIND) Mohammed Hossain - District Council 37 Public Employee Union Nora Howe - NAACP Legal Defense Fund Ignacia Lolas Ojeda - Make the Road NY Danielle McCoy - Racial Justice project Nusrat Mowla - Crime Victims Treatment Center (Domestic Violence) Pablo Rojo - Legal Aid Society (Criminal Defense) Cesar Ruiz - LatinoJustice PRLDEF Nowmee Shehab - Brooklyn Defenders Service (Youth and Communities) Ever since the Trayvon Martin shooting in 2012, I have been an organizer. I’m the first person to get a degree in my working class Mexican-American family. At Legal Aid in the Bronx this summer, I am “ fighting the criminalization of poverty head on. Pablo Rojo I am interested in legal work that ends school segregation, ensures fair funding, and ends the school to prison pipeline. As a summer intern at NAACP LDF, funded by the JL Greene Foundation, I’m focused on education equity, and have also been able to work on LDF voting rights projects, building on my work as a Sorensen Center Voting Rights Initiative student leader. Nora Howe ” Support from the Jerome L. Greene Foundation enables a larger cohort of Fellows to address global issues affecting communities in NYC. Founded in 2014 and named after Ted Sorensen, the Sorensen Center nurtures and trains new generations of social justice lawyers.