Harvard Kennedy School Journal of Hispanic Policy a Harvard Kennedy School Student Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Order Granting Preliminary Injunction

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, NORTHERN DIVISION CENTRAL ALABAMA FAIR ) HOUSING CENTER, et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) CIVIL ACTION NO. v. ) 2:11cv982-MHT ) (WO) JULIE MAGEE, in her ) official capacity as ) Alabama Revenue ) Commissioner, and ) JIMMY STUBBS, in his ) official capacity as ) Elmore County Probate ) Judge, ) ) Defendants. ) OPINION This lawsuit is a challenge to the application of § 30 of the Beason-Hammon Alabama Taxpayer and Citizen Protection Act (commonly referred to as “HB 56”), 2011 Ala. Laws 535, which, when combined with another Alabama statute, essentially prohibits individuals who cannot prove their citizenship status from staying in their manufactured homes. The plaintiffs are the Central Alabama Fair Housing Center, the Fair Housing Center of Northern Alabama, the Center for Fair Housing, Inc., and two individuals proceeding under pseudonym as John Doe #1 and John Doe #2. The defendants are Julie Magee, in her official capacity as Alabama Revenue Commissioner, and Jimmy Stubbs, in his official capacity as Elmore County Probate Judge. The plaintiffs claim, among other things, that this application of HB 56 violates the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution (as enforced through 42 U.S.C. § 1983) and the Fair Housing Act (“FHA”), 42 U.S.C. § 3604. The jurisdiction of the court has been invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1343. This as-applied challenge to HB 56 is now before the court on the plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction. As explained below, the motion will be granted. 2 I. BACKGROUND A. Passage of HB 56 In June 2011, the Alabama legislature passed a comprehensive and far-reaching state immigration law: HB 56. -

Visítennos, DC Está Abierto VÍCTOR CAYCHO La Alcaldesa También Harris: Alto a La Lucha Interna WASHINGTON HISPANIC Agradeció a La Población De Por La Migración

Washington Maryland Virginia Viernes 2 de julio del 2021 www.washingtonhispanic.com Volumen 14 número 736 Feliz Día Estados Unidos El 4 de Julio es una celebración a la libertad y soberanía del país. WASHINGTON en las mesas cada 4 de julio HISPANIC desde las primeras celebra- ciones. ada país tie- ne su forma ¿Qué se celebra el 4 de de celebrar julio en Estados Unidos? aquello que El 4 de julio se conme- los identifica mora la independencia de Ccomo nación. las 13 colonias británicas, En el caso de Estados aunque la declaración no Unidos, el 4 de julio es una se firmó en esa fecha. celebración a la libertad y De acuerdo con el histo- soberanía del país, por eso riador David McCullough, las grandes ciudades reali- fue el 2 de julio. Pero fue un zan espectáculos con fue- 4 de julio de 1776 en que se gos artificiales que atraen a adoptó por unanimidad, y millones de personas fren- se anunció oficialmente la te a ríos, puentes u otros separación de las colonias destinos turísticos, asi es- de Gran Bretaña. ta programado en todo el DMV . Los estadouniden- ¿Por qué es importan- ses suelen gastar más de te el 4 de julio en Estados 7.000 millones de dólares Unidos? en comida para esta fecha, Porque se trata de la con platillos tradicionales celebración de indepen- como los hot dog, cerveza dencia, ya que para ese y barbacoas en casa. Ade- entonces las colonias ya más, consumen el salmón, no querían ser gobernadas alimento tradicional, ya por Gran Bretaña y querían que era un producto muy convertirse en un país inde- abundante en Nueva Ingla- pendiente. -

Fixing Alabama's Public School Enrollment Requirements in H.B. 56: Eliminating Obstacles to an Education for Unauthorized Immigrant Children

Brigham Young University Education and Law Journal Volume 2014 Number 2 Article 4 Summer 6-1-2014 Fixing Alabama's Public School Enrollment Requirements in H.B. 56: Eliminating Obstacles to an Education for Unauthorized Immigrant Children Sean Mussey Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/elj Part of the Education Commons, Education Law Commons, and the Immigration Law Commons Recommended Citation Sean Mussey, Fixing Alabama's Public School Enrollment Requirements in H.B. 56: Eliminating Obstacles to an Education for Unauthorized Immigrant Children, 2014 BYU Educ. & L.J. 233 (2014). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/elj/vol2014/iss2/4 . This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brigham Young University Education and Law Journal by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mussey Macro.docx (Do Not Delete) 5/28/14 3:45 PM FIXING ALABAMA’S PUBLIC SCHOOL ENROLLMENT REQUIREMENTS IN H.B. 56: ELIMINATING OBSTACLES TO AN EDUCATION FOR UNAUTHORIZED IMMIGRANT CHILDREN Sean Mussey∗ I. INTRODUCTION In 2011, Alabama enacted a comprehensive immigration law primarily aimed at addressing unauthorized immigration in the state.1 The Beason-Hammon Alabama Taxpayer Citizen and Protection Act (H.B. 56) impacts many areas of an unauthorized immigrant’s life, including law enforcement, transportation, housing, employment, and children’s participation in public schools.2 -

PRACHTER: Hi, I'm Richard Prachter from the Miami Herald

Bob Garfield, author of “The Chaos Scenario” (Stielstra Publishing) Appearance at Miami Book Fair International 2009 PACHTER: Hi, I’m Richard Pachter from the Miami Herald. I’m the Business Books Columnist for Business Monday. I’m going to introduce Chris and Bob. Christopher Kenneally responsible for organizing and hosting programs at Copyright Clearance Center. He’s an award-winning journalist and author of Massachusetts 101: A History of the State, from Red Coats to Red Sox. He’s reported on education, business, travel, culture and technology for The New York Times, The Boston Globe, the LA Times, the Independent of London and other publications. His articles on blogging, search engines and the impact of technology on writers have appeared in the Boston Business Journal, Washington Business Journal and Book Tech Magazine, among other publications. He’s also host and moderator of the series Beyond the Book, which his frequently broadcast on C- SPAN’s Book TV and on Book Television in Canada. And Chris tells me that this panel is going to be part of a podcast in the future. So we can look forward to that. To Chris’s left is Bob Garfield. After I reviewed Bob Garfield’s terrific book, And Now a Few Words From Me, in 2003, I received an e-mail from him that said, among other things, I want to have your child. This was an interesting offer, but I’m married with three kids, and Bob isn’t quite my type, though I appreciated the opportunity and his enthusiasm. After all, Bob Garfield is a living legend. -

Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason Mccoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Professional Projects from the College of Journalism Journalism and Mass Communications, College of and Mass Communications Spring 4-18-2019 Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason McCoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Other Communication Commons McCoy, Jason, "Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media" (2019). Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects/20 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and Mass Communications, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason Mccoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln This paper will examine the development of modern media ethics and will show that this set of guidelines can and perhaps should be revised and improved to match the challenges of an economic and political system that has taken advantage of guidelines such as “objective reporting” by creating too many false equivalencies. This paper will end by providing a few reforms that can create a better media environment and keep the public better informed. As it was important for journalism to improve from partisan media to objective reporting in the past, it is important today that journalism improves its practices to address the right-wing media’s attack on journalism and avoid too many false equivalencies. -

Brooklyn Law Notes| the MAGAZINE of BROOKLYN LAW SCHOOL SPRING 2018

Brooklyn Law Notes| THE MAGAZINE OF BROOKLYN LAW SCHOOL SPRING 2018 Big Deals Graduates at the forefront of the booming M&A business SUPPORT THE ANNUAL FUND YOUR CONTRIBUTIONS HELP US • Strengthen scholarships and financial aid programs • Support student organizations • Expand our faculty and support their nationally recognized scholarship • Maintain our facilities • Plan for the future of the Law School Support the Annual Fund by making a gift TODAY Visit brooklaw.edu/give or call Kamille James at 718-780-7505 Dean’s Message Preparing the Next Generation of Lawyers ROSPECTIVE STUDENTS OFTEN ask about could potentially the best subject areas to focus on to prepare for qualify you for law school. My answer is that it matters less what several careers.” you study than how you study. To be successful, it Boyd is right. We is useful to study something that you love and dig made this modest Pdeep in a field that best fits your interests and talents. Abraham change in our own Lincoln, perhaps America’s most famous and respected lawyer, admissions process advised aspiring lawyers: “If you are resolutely determined to encourage to make a lawyer of yourself, the thing is more than half done highly qualified students from diverse academic and work already…. Get the books, and read and study them till you backgrounds to apply and pursue a law degree. Our Law understand them in their principal features; and that is the School long has attracted students who come to us with deep main thing.” experience and study in myriad fields. Currently, more than Today, with so much information and knowledge available 60 percent of our applicants have one to five years of work in cyberspace, Lincoln’s advice is more relevant than ever. -

Breaking Down the Thousand Petty Fortresses of State Self-Deportation Laws

Pace Law Review Volume 34 Issue 2 Spring 2014 Article 7 April 2014 The Right to Travel: Breaking Down the Thousand Petty Fortresses of State Self-Deportation Laws R. Linus Chan University of Minnesota Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Immigration Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation R. Linus Chan, The Right to Travel: Breaking Down the Thousand Petty Fortresses of State Self- Deportation Laws, 34 Pace L. Rev. 814 (2014) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr/vol34/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Right to Travel: Breaking Down the Thousand Petty Fortresses of State Self- Deportation Laws R. Linus Chan* Introduction The vanishing began Wednesday night, the most frightened families packing up their cars as soon as they heard the news. They left behind mobile homes, sold fully furnished for a thousand dollars or even less. Or they just closed up and, in a gesture of optimism, left the keys with a neighbor. Dogs were fed one last time; if no home could be found, they were simply unleashed. Two, [five], [ten] years of living here, and then gone in a matter of days, to Tennessee, Illinois, Oregon, Florida, Arkansas, Mexico—who knows? Anywhere but Alabama.1 This mass exodus from Albertville, Alabama was not the result of a natural disaster or fears of an invasion by hostile forces. -

The Anti-Immigrant Game

Op-Ed The anti-immigrant game Laws such as Arizona's SB 1070 are not natural responses to undue hardship but are products of partisan politics. Opponents of SB 1070 raise their fists after unfurling an enormous banner from the beam of a 30-story high construction crane in downtown Phoenix, Arizona in 2010. If upheld, Arizona's SB 1070 would require local police in most circumstances to determine the immigration status of anyone they stop based only on a reasonable suspicion that the person is unlawfully in this country. (Los Angeles Times / April 23, 2012) By Pratheepan Gulasekaram and Karthick Ramakrishnan April 24, 2012 The Supreme Court hears oral arguments Wednesday on the constitutionality of Arizona's 2010 immigration enforcement law. If upheld, SB 1070 would require local police in most circumstances to determine the immigration status of anyone they stop based only on a reasonable suspicion that the person is unlawfully in this country. It would also compel residents to carry their immigration papers at all times and create state immigration crimes distinct from what is covered by federal law. A few other states, such as Alabama and Georgia, and some cities have passed similar laws, and many more may consider such laws if the Supreme Court finds Arizona's law to be constitutional. The primary legal debate in U.S. vs. Arizona will focus on the issue of whether a state government can engage in immigration enforcement without the explicit consent of the federal government. The state of Arizona will argue that its measure simply complements federal enforcement, while the federal government will argue that Arizona's law undermines national authority and that immigration enforcement is an exclusively federal responsibility. -

REPORT Donations Are Fully Tax-Deductible

SUPPORT THE NYCLU JOIN AND BECOME A CARD-CARRYING MEMBER Basic individual membership is only $20 per year, joint membership NEW YORK is $35. NYCLU membership automatically extends to the national CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION American Civil Liberties Union and to your local chapter. Membership is not tax-deductible and supports our legal, legislative, lobbying, educational and community organizing efforts. ANNUAL MAKE A TAX-DEDUCTIBLE GIFT Because the NYCLU Foundation is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, REPORT donations are fully tax-deductible. The NYCLU Foundation supports litigation, advocacy and public education but does not fund legislative lobbying, which cannot be supported by tax-deductible funds. BECOME AN NYCLU ACTIVIST 2013 NYCLU activists organize coalitions, lobby elected officials, protest civil liberties violations and participate in web-based action campaigns THE DESILVER SOCIETY Named for Albert DeSilver, one of the founders of the ACLU, the DeSilver Society supports the organization through bequests, retirement plans, beneficiary designations or other legacy gifts. This special group of supporters helps secure civil liberties for future generations. THE AMICUS CLUB Lawyers and legal professionals are invited to join our Amicus Club with a donation equal to the value of one to four billable hours. Club events offer members the opportunity to network, stay informed of legal developments in the field of civil liberties and earn CLE credits. THE EASTMAN SOCIETY Named for the ACLU’s co-founder, Crystal Eastman, the Eastman Society honors and recognizes those patrons who make an annual gift of $5,000 or more. Society members receive a variety of benefits. Go to www.nyclu.org to sign up and stand up for civil liberties. -

Confronting the Cancer in Her Family

A8 WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 26, 2015 LATIMES.COM LATIMES.COMA10 WEDNESDAY, OCTOBERLA 26,TIMES 2015 .COMA9 $2.75 DESIGNATED AREAS HIGHER ©2019 WST SATURDAY,APRIL 27, 2019 latimes.com Confronting the cancer in her family [Breast cancer, from A1] such as religion and family, grandmother Maria Elena may keep Latinas from Uribe when she was in her getting tested, and econo- USC HOME 70s. It came after her grand- mic disparities may prevent mother in her 60s and then many from getting health her mother at age 49. One insurance. aunt survived cancer a few Everyone, men and suffers years ago; another finished women, has two genes PRICE treatment in February. known as BRCA1 and It seemed only a matter BRCA2. Latinas are not of time before it came for necessarily more likely to be another her. But Campoverdi’s carriers of a harmful muta- DROP IS approach to the deadly tion in either BRCA1 or disease typified a genera- BRCA2, or to be diagnosed tional shift. While others in with breast cancer com- setback her family ignored a lump, pared with other ethnic FIRST IN or let the doctors take the populations. However, they lead, Campoverdi said she are less likely to get prevent- decided to become “the ive testing, such as mammo- Cardiology fellowship CEO of her own body.” grams, and are often diag- clouded by sex-assault 7 YEARS In 2014 , Campoverdi nosed at later stages, said tested positive for a muta- Susan Domchek, executive lawsuit will lose its tion in her BRCA2 gene, director of the Basser Cen- national accreditation. -

Read the 2018-2019 Shorenstein Center Annual Report

Annual Report 2018–2019 Contents Letter from the Director 2 2018–2019 Highlights 4 Areas of Focus Technology and Social Change Research Project 6 Misinformation Research 8 Digital Platforms and Democracy 10 News Quality Journalist’s Resource 12 The Goldsmith Awards 15 News Sustainability 18 Race & Equity 20 Events Annual Lectures 22 Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics 23 Salant Lecture on Freedom of the Press 33 Speaker Series 41 The Student Experience 43 Fellows 45 Staff, Faculty, Board, and Supporters 47 From the Director Like the air we breathe and the water we drink, the information we consume sustains the health of the body politic. Good information nourishes democracy; bad information poisons it. The mission of the Shorenstein Center is to support and protect the information ecosystem. This means promoting access to reliable information through our work with journalists, policymakers, civil society, and scholars, while also slowing the spread of bad information, from hate speech to “fake news” to all kinds of distortion and media manipulation. The public square has always had to contend with liars, propagandists, dividers, and demagogues. But the tools for creating toxic information are more powerful and widely available than ever before, and the effects more dangerous. How our generation responds to threats we did not foresee, fueled by technologies we have not contained, is the central challenge of our age. How do journalists cover the impact of misinformation without spreading it further? How do technology companies, -

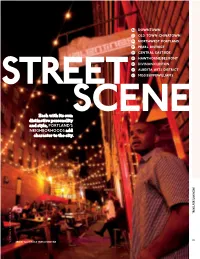

Each with Its Own Distinctive Personality and Style, PORTLAND's

THE GET READY FOR YOUR 34 DOWNTOWN way to NEXT 35 OLD TOWN CHINATOWN 36 NORTHWEST PORTLAND 37 PEARL DISTRICT 38 CENTRAL EASTSIDE 39 HAWTHORNE/BELMONT . 40 DIVISION/CLINTON “10 Best in U.S.” 41 ALBERTA ARTS DISTRICT –Fodor’s Travel STREET42 MISSISSIPPI/WILLIAMS -TripAdvisor Each with its own SCENE distinctive personality and style, PORTLAND’S NEIGHBORHOODS add character to the city. ney St Pearl District NW Irving St NW Irving St ve ve A A A th oyt St th NW Hoyt St 6 6 ve ve A A Couch Park A W 1 W N St th NW Glisan St th NW Glisan 5 W 1 W N NW Flanders St ders St TRAVELPORTLAND.COM verett St NW Everett St COME VISIT US! ve e A l NW Davis St v P A Newberg, Oregon th 4 h KEEN Garage Portland t nity 0 i r 2 W 1 NW Couch St T 503.625.7385 N 505 NW 13th AVE NW NW vistaballoon.com NW W Burnside St Portland OR, 97209 405 SW ve PHOTOGRAPH BY AMYPHOTOGRAPH OUELLETTEBY ANKENY ALLEY IN OLD TOWN CHINATOWN A 33 JELD- h 3t 1 e Smith Lake Lake Force North Portland Harbor Smith Lake Columbia Slough Lake Force Columbia River Smith and Bybee Lakes Park North Portland Harbor N Swift Hwy Columbia Slough Delta Park Slough Columbia Slough Portland Intl Airport Columbia Slough Drainage Canal Drainage Canal Columbia Slough Columbia Slough Columbia Slough an Island Basin Sw Columbia Slough Columbia Slo ugh Columbia Columbia Slough Slough Beach Elem. School EAT PLAY The 1 Alder Street food cart pod (S.W.