Private Armies and Personal Power in the Late Roman Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story of the Byzantine Empire

THE STO RY O F T HE NATIO NS L LU T T E E R VO L . I z M o I S A . P , R D , T H E E AR L I E R VO L UM E S A R E f I N E F R E E B P o AS A . SO T H STO R Y O G E C . y r . I . HARR R F R E B TH U ILM A N T HE STO Y O O M . y A R R G EW B P f A K O S E R F T HE S . o S . M T HE ST O Y O J y r . J . H R B Z N R O F DE . A R A coz I T HE ST O Y C HA L A . y . — R F E R N . B S B ING O U L THE ST O Y O G MA Y y . AR G D F N W B P f H B YE S E N o . H . O T HE ST O R Y O O R A Y . y r N E n E B . E . a d S SA H T HE ST O R Y O F SP A I . y U N AL N B P R of. A . VAM B Y T HE STO R Y O F H U GA R Y . y r E ST R O F E B P of L E TH E O Y C A RT H A G . -

Conference Programme Europe’S Premier Microwave, Rf, Wireless and Radar Event

SIX DAYS THREE CONFERENCES THREE FORUMS ONE EXHIBITION EUROPEAN MICROWAVE WEEK 2020 JAARBEURS CONVENTION CENTRE UTRECHT – THE NETHERLANDS 10 – 15 JANUARY 2021 10-15 JANUARY 2021 EUROPEAN MICROWAVE WEEK 2020 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME EUROPE’S PREMIER MICROWAVE, RF, WIRELESS AND RADAR EVENT THE ART OF MICROWAVES Register online at: www.eumweek.com 2 – WWW.EUMWEEK.COM SPONSORS TABLE OF CONTENTS WWW.EUMWEEK.COM – 3 Promoting Table of Contents European Microwaves WELCOME MESSAGES STUDENT ACTIVITIES AND WiM Welcome to the 23rd European Microwave Week · · · · · 5 Welcome from the Student Activities Chair · · · · · · 38 Welcome from the President of the European Student Design Competitions · · · · · · · · · · · · 39 Microwave Association ·· · · · · · · · · · · · · · 6 Women in Microwaves · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 39 Welcome to the 15th European Microwave Integrated Career Platform · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 40 Circuits Conference · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 7 5th European Microwave Student School · · · · · · · 42 Archiving through Editing the International Journal Welcome to the 50th European Microwave Conference · · 8 Tom Brazil Doctoral School of Microwaves · · · · · · · 43 the Knowledge Centre of Microwave and Wireless Welcome to the 17th European Radar Conference · · · · · 9 Welcome from the General TPC Chair · · · · · · · · ·10 Records papers written by the best Technologies CONFERENCE PROGRAMME international scientists in our secure database. The Journal solicits original and review Sunday 10th January 2021 · · · · · · · · · · · -

RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian's “Great

ABSTRACT RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy. (Under the direction of Prof. S. Thomas Parker) In the year 303, the Roman Emperor Diocletian and the other members of the Tetrarchy launched a series of persecutions against Christians that is remembered as the most severe, widespread, and systematic persecution in the Church’s history. Around that time, the Tetrarchy also issued a rescript to the Pronconsul of Africa ordering similar persecutory actions against a religious group known as the Manichaeans. At first glance, the Tetrarchy’s actions appear to be the result of tensions between traditional classical paganism and religious groups that were not part of that system. However, when the status of Jewish populations in the Empire is examined, it becomes apparent that the Tetrarchy only persecuted Christians and Manichaeans. This thesis explores the relationship between the Tetrarchy and each of these three minority groups as it attempts to understand the Tetrarchy’s policies towards minority religions. In doing so, this thesis will discuss the relationship between the Roman state and minority religious groups in the era just before the Empire’s formal conversion to Christianity. It is only around certain moments in the various religions’ relationships with the state that the Tetrarchs order violence. Consequently, I argue that violence towards minority religions was a means by which the Roman state policed boundaries around its conceptions of Roman identity. © Copyright 2016 Carl Ross Rice All Rights Reserved Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy by Carl Ross Rice A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: ______________________________ _______________________________ S. -

Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 5-16-2016 12:00 AM Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain Robert Jackson Woodcock The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Professor Alexander Meyer The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Classics A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Robert Jackson Woodcock 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Indo- European Linguistics and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Woodcock, Robert Jackson, "Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3775. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3775 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Language is one of the most significant aspects of cultural identity. This thesis examines the evidence of languages in contact in Roman Britain in order to determine the role that language played in defining the identities of the inhabitants of this Roman province. All forms of documentary evidence from monumental stone epigraphy to ownership marks scratched onto pottery are analyzed for indications of bilingualism and language contact in Roman Britain. The language and subject matter of the Vindolanda writing tablets from a Roman army fort on the northern frontier are analyzed for indications of bilingual interactions between Roman soldiers and their native surroundings, as well as Celtic interference on the Latin that was written and spoken by the Roman army. -

CILICIA: the FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES in ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson

CILICIA: THE FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES IN ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson Summary This article explores the origin of the Christian church in Anatolia. While individual believers undoubtedly entered Anatolia during the 30s after the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:9–10), the book of Acts suggests that it was not until the following decade that the first church was organized. For it was at Antioch, the capital of the Roman province of Syria, that the first Christians appeared (Acts 11:20–26). Yet two obscure references in Acts point to the organization of churches in Cilicia at an earlier date. Among the addressees of the letter drafted by the Jerusalem council were the churches in Cilicia (Acts 15:23). Later Paul visited these same churches at the beginning of his second ministry journey (Acts 15:41). Paul’s relationship to these churches points to this apostle as their founder. Since his home was the Cilician city of Tarsus, to which he returned after his conversion (Gal. 1:21; Acts 9:30), Paul was apparently active in church planting during his so-called ‘silent years’. The core of these churches undoubtedly consisted of Diaspora Jews who, like Paul’s family, lived in the region. Jews from Cilicia were members of a Synagogue of the Freedmen in Jerusalem, to which Paul was associated during his time in Jerusalem (Acts 6:9). Antiochus IV (175–164 BC) hellenized and urbanized Cilicia during his reign; the Romans around 39 BC added Cilicia Pedias to the province of Syria. Four cities along with Tarsus, located along or near the Pilgrim Road that transects Anatolia, constitute the most likely sites for the Cilician churches. -

295 Emanuela Borgia (Rome) CILICIA and the ROMAN EMPIRE

EMANUELA BORGIA, CILICIA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 16/2017 ISSN 2082-5951 DOI 10.14746/seg.2017.16.15 Emanuela Borgia (Rome) CILICIA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE: REFLECTIONS ON PROVINCIA CILICIA AND ITS ROMANISATION Abstract This paper aims at the study of the Roman province of Cilicia, whose formation process was quite long (from the 1st century BC to 72 AD) and complicated by various events. Firstly, it will focus on a more precise determination of the geographic limits of the region, which are not clear and quite ambiguous in the ancient sources. Secondly, the author will thoroughly analyze the formation of the province itself and its progressive Romanization. Finally, political organization of Cilicia within the Roman empire in its different forms throughout time will be taken into account. Key words Cilicia, provincia Cilicia, Roman empire, Romanization, client kings 295 STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 16/2017 · ROME AND THE PROVINCES Quos timuit superat, quos superavit amat (Rut. Nam., De Reditu suo, I, 72) This paper attempts a systematic approach to the study of the Roman province of Cilicia, whose formation process was quite long and characterized by a complicated sequence of historical and political events. The main question is formulated drawing on – though in a different geographic context – the words of G. Alföldy1: can we consider Cilicia a „typical” province of the Roman empire and how can we determine the peculiarities of this province? Moreover, always recalling a point emphasized by G. Alföldy, we have to take into account that, in order to understand the characteristics of a province, it is fundamental to appreciate its level of Romanization and its importance within the empire from the economic, political, military and cultural points of view2. -

Antioch University New England Student Handbook and Course Listing

Academic Catalog 2012-2013 Antioch University New England Student Handbook 2012-2013 http://www.antiochne.edu/handbook/ On behalf of all faculty and staff, I am pleased to welcome you to Antioch University New England. The Antioch University New England community is made up of students, faculty, and staff of diverse backgrounds and experience. Students come to our campus from throughout the U.S. and around the world to pursue graduate study and change the world for the better. We share a common commitment to Antioch University’s mission with our colleagues at the other Antioch University campuses in Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, Seattle, and Yellow Springs, Ohio. All Antioch University campuses are covered by overarching policies; AUNE academic and administrative departments are guided by both these and our own campus policies and procedures. This Student Handbook is a reference for registration, academic, and financial policies and procedures, as well as for campus resources and academic supports. You are responsible for familiarizing yourself with all pertinent policies and procedures and for adhering to them throughout your graduate studies. Of particular note are the Student Rights and Responsibilities. Again, welcome to Antioch University New England. I sincerely hope your graduate studies are both personally and professionally rewarding. David A. Caruso, PhD President 1 of 204 2012-2013 Degree Requirements Students are required to fulfill the set of course, competency area, and internship/practicum requirements in effect for the semester and year they enrolled as a degree student. Please be sure to refer to the correct academic year when consulting these pages. -

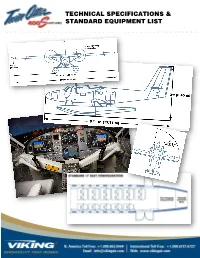

Technical Specifications & Standard Equipment List

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS & STANDARD EQUIPMENT LIST TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS & STANDARD EQUIPMENT LIST Aircraft Overview The Viking 400S Twin Otter (“400S”) is an all-metal, high wing monoplane, powered by two wing-mounted turboprop engines, The aircraft is delivered with two Pratt and Whitney PT6A-27 driving three-bladed, reversible pitch, fully feathering propellers. engines that incorporate platinum coated CT blades. The aircraft carries a pilot, co-pilot, and up to 17 passengers in standard configuration with a 19 or 15 passenger option. The The 400S will be supplied with new generation composite floats aircraft is a floatplane with no fixed landing gear. that reduce the overall aircraft weight (when compared to Series 400 Twin Otters configured for complex utility or special mission The 400S is an adaptation of the Viking DHC-6 Series 400 Twin operations). The weight savings allows the standard 400S to Otter (“Series 400”). It is specifically designed as an economical carry a 17 passenger load 150 nautical miles with typical seaplane for commercial operations on short to medium reserves, at an average passenger and baggage weight of 191 segments. lbs. (86.5 kg.). The Series 400 is an updated version of the Series 300 Twin Otter. The changes made in developing the Series 400 were 1. General Description selected to take advantage of newer technologies that permit more reliable and economical operations. Aircraft dimensions, Aircraft Dimensions construction techniques, and primary structure have not Overall Height 21 ft. 0 in (6.40 m) changed. Overall Length 51 ft. 9 in (15.77 m) Wing Span 65 ft. 0 in (19.81 m) The aircraft is manufactured at Viking Air Limited facilities in Horizontal Tail Span 20 ft. -

Egyptian Units and the Reliability of the Notitia Dignitatum, Pars Oriens

Imperium and Officium Working Papers (IOWP) Egyptian Units and the reliability of the Notitia dignitatum, pars Oriens Version 01 April 2014 Anna Maria Kaiser (University of Vienna, Department of Ancient History, Papyrology and Epigraphy) Abstract: This study argues for the reliability of the Egyptian military lists in the pars Oriens of the Notitia Dignitatum and opposes the views of some scho-lars, who see the Not.Dig. as a purely ideological composition unrelated to historical reality and without value as an historical source. Deniers of the Not.Dig.’s reliability generally ignore the documentary evidence. For Egypt, papyrological documentation verifies the Not.Dig.’s accuracy—a circumstance not so readily available for other parts of the Roman Empire—and, complemented by archaeological evidence, provides a strong argument for the completeness and reliability of at least the Egyptian sections. Thus the probability of the Not.Dig.’s accuracy for other sections of the pars Oriens is also corroborated. © Anna Maria Kaiser 2014 [email protected] 1 Anna Maria Kaiser Egyptian Units and the reliability of the Notitia Dignitatum, pars Oriens* This study argues for the reliability of the Egyptian military lists in the pars Oriens of the Notitia Dignitatum and opposes the views of some scholars, who see the Not.Dig. as a purely ideological composition unrelated to historical reality and without value as an historical source. Deniers of the Not.Dig.’s reliability generally ignore the documentary evidence. For Egypt, papyrological documentation verifies the Not.Dig.’s accuracy—a circumstance not so readily available for other parts of the Roman Empire—and, complemented by archaeological evidence, provides a strong argument for the completeness and reliability of at least the Egyptian sections. -

BOOK 15 the Time of the Reign of Zeno to the Time of the Reign of Anastasios

BOOK 15 The Time of the Reign of Zeno to the Time of the Reign of Anastasios 1. (377) After the reign of Leo the Younger, the most sacred Zeno reigned for 15 years. In the eighth month of his reign, he appointed Peter, the p!JrBmomr.ios of St Euphemia's in Chalkedon, as bishop and patriarch of Antioch the Great and sent him to Antioch. 2. After two years and ten months of his reign, he quarrelled with his mother-in-law, Verina, over a request she had made of him but which he had refused her, and so his mother-in-law, the lady Verina, began to plot against him. Terrified that he would be assassinated by someone in the palace, since his mother-in-law was living in the palace with him, he made a processusto Chalkedon and escaped from there using post-horses, and got away to Isauria even though he was emperor. (378) The empress Ariadne, who had also secretly fled from her mother, caught up with him in Isauria and remained with her husband. 3, After the emperor Zeno and Ariadne had fled, the lady Verina inunediately chose an emperor by crowning her brother Basiliscus. Basiliscus, the brother of Zeno's mother-in-law Verina, reigned for two years. When Verina had made Basiliscus emperor, she also named him as consul, together with Armatus who had been appointed by Basiliscus as AD476 senior lllc1q.ister mii1"tum prBesentalis. These two held the consulship. As soon as Basiliscus began to reign, he crowned his son, named Marcus, as emperor. -

Antonis Antoniou · Kkismettin · Ajabu!

JULY 2021 Antonis Antoniou · Kkismettin · Ajabu! 2. Canzoniere Grecanico Salentino (CGS) · Meridiana · 22. Apo Sahagian · Ler Mer · Chimichanga (-) Ponderosa Music (1) 23. Katerina Papadopoulou & Anastatica · Anastasis · 3. Toumani Diabaté and The London Symphony Orchestra · Saphrane (19) Kôrôlén · World Circuit (10) 24. BLK JKS · Abantu / Before Humans · Glitterbeat (-) 4. Ballaké Sissoko · Djourou · Nø Førmat! (2) 25. Davide Ambrogio · Evocazioni e Invocazioni · Catalea 5. Ben Aylon · Xalam · Riverboat / World Music Network (6) (-) 6. Dobet Gnahoré · Couleur · Cumbancha (-) 26. Saucējas · Dabā · Lauska / CPL-Music (31) 7. Balkan Taksim · Disko Telegraf · Buda Musique (5) 27. V.A. · Hanin: Field Recordings In Syria 2008/2009 · 8. V.A. · Henna: Young Female Voices from Palestine · Kirkelig Worlds Within Worlds (-) Kulturverksted (-) 28. Juana Molina · Segundo (Remastered) · Crammed Discs 9. Samba Touré · Binga · Glitterbeat (3) (-) 10. Jupiter & Okwess · Na Kozonga · Zamora Label (7) 29. Bagga Khan · Bhajan · Amarrass (15) 11. Kasai Allstars · Black Ants Always Fly Together, One Bangle 30. Alena Murang · Sky Songs · Wind Music International Makes No Sound · Crammed Discs (12) Corporation (-) 12. Sofía Rei · Umbral · Cascabelera (-) 31. Oumar Ndiaye · Soutoura · Smokey Hormel (-) 13. Hamdi Benani, Mehdi Haddab & Speed Caravan · Nuba 32. Xurxo Fernandes · Levaino! · Xurxo Fernandes (29) Nova · Buda Musique (27) 33. Omar Sosa · An East African Journey · Otá (24) 14. Comorian · We Are an Island, but We're Not Alone · 34. San Salvador · La Grande Folie · La Grande Folie / Glitterbeat (17) Pagans / MDC (11) 15. Dagadana · Tobie · Agora Muzyka (18) 35. Helsinki-Cotonou Ensemble · Helsinki-Cotonou 16. Luís Peixoto · Geodesia · Groove Punch Studios (20) Ensemble · flowfish.music (-) 17. Femi Kuti & Made Kuti · Legacy + · Partisan (30) 36. -

Emperors and Generals in the Fourth Century Doug Lee Roman

Emperors and Generals in the Fourth Century Doug Lee Roman emperors had always been conscious of the political power of the military establishment. In his well-known assessment of the secrets of Augustus’ success, Tacitus observed that he had “won over the soldiers with gifts”,1 while Septimius Severus is famously reported to have advised his sons to “be harmonious, enrich the soldiers, and despise the rest”.2 Since both men had gained power after fiercely contested periods of civil war, it is hardly surprising that they were mindful of the importance of conciliating this particular constituency. Emperors’ awareness of this can only have been intensified by the prolonged and repeated incidence of civil war during the mid third century, as well as by emperors themselves increasingly coming from military backgrounds during this period. At the same time, the sheer frequency with which armies were able to make and unmake emperors in the mid third century must have served to reinforce soldiers’ sense of their potential to influence the empire’s affairs and extract concessions from emperors. The stage was thus set for a fourth century in which the stakes were high in relations between emperors and the military, with a distinct risk that, if those relations were not handled judiciously, the empire might fragment, as it almost did in the 260s and 270s. 1 Tac. Ann. 1.2. 2 Cass. Dio 76.15.2. Just as emperors of earlier centuries had taken care to conciliate the rank and file by various means,3 so too fourth-century emperors deployed a range of measures designed to win and retain the loyalties of the soldiery.