When Pixels Speak: Why Video Games Deserve Free Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name That! 90S Toy Answers – Adder Apps Level 1 1. Talkboy 2. Bop It 3

5. Spice Girls Dolls Level 6 Level 9 6. Tamagotchi 1. Jenga 1. Puffkins 7. Laser Challenge 2. Weebles 2. Brain Warp 8. Super Soaker 3. He-Man 3. Snardvark 9. Creepy Crawlers 4. Snoopy Sno Cone 4. Chatter Ring Name That! 90s Toy Answers 10. Talkback Dear diary Machine 5. Dragon Flyz – Adder Apps 11. Nerf Guns 5. Dungeons and Dragons 6. Tazos 12. Don’t Wake Daddy* 6. Risk 7. Doodle Bears Level 1 7. Captain Action 8. Neopets 1. Talkboy Level 4 8. Pogo Stick 9. Quints 2. Bop It 1. Jibba Jabba 9. Barrel of Monkeys 10. Vortex Football 3. Buzz Lightyear 2. Hit Clips 10. Koosh Balls 11. Party Mania 4. Crocodile Dentist 3. Bumble Ball 11. BB Gun 12. Zbots 5. Woody 4. Moon Shoes 12. Ker Plunk 6. Pogs 5. Sega Genesis Level 10 7. Nintendo 64 6. Beanie Babies Level 7 1. Fantastic Flowers 8. Furby 7. Mr Potato Head 1. Pretty Pretty Princess 2. Zoids 9. Playstation 8. Polly Pocket 2. Power Rangers 3. Ouija Boards 10. Power Wheels 9. Silly Putty 3. Spin Art 4. Magna Doodle 11. Game Boy 10. Mighty Max 4. Tonka Truck 5. Sticky Hands 12. Easy Bake Oven 11. Sock Em Boppers 5. Wonderful Waterful 6. Boggle 12. Mr Bucket 6. Slip n Slide 7. Lite Brite Level 2 7. Baby Sinclair 8. Cootie 1. Uno Level 5 8. Roller Blades 9. Fashion Plates 2. Barbie 1. Glitter Magic Wand 9. Laser Pointer 10. Hypercolor T-Shirt 3. Tiddlywinks 2. Stretch Armstrong 10. Slap Bracelet 11. -

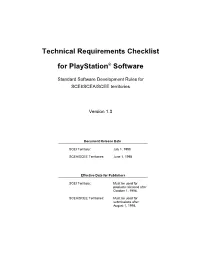

Tech Note\Technical Requirements Checklist

Technical Requirements Checklist for PlayStation® Software Standard Software Development Rules for SCEI/SCEA/SCEE territories Version 1.3 Document Release Date SCEI Territory: July 1, 1998 SCEA/SCEE Territories: June 1, 1998 Effective Date for Publishers SCEI Territory: Must be used for products released after October 1, 1998. SCEA/SCEE Territories: Must be used for submissions after August 1, 1998. © 1996, 1997, 1998 Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. Document Version: 1.3, June 1998 The Technical Requirements Checklist for PlayStation Software is supplied pursuant to and subject to the terms of the Sony Computer Entertainment PlayStation publisher and developer Agreements. The content of this book is Confidential Information of Sony Computer Entertainment. PlayStation and PlayStation logos are trademarks of Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. All other trademarks are property of their respective owners and/or their licensors. HYPER BLASTER® is a registered trademark of Konami Co., Ltd. Guncon™, G-Con 45™ are trademarks of NAMCO LTD. neGcon® is registered trademark of NAMCO LTD. The information in the Technical Requirements Checklist for PlayStation Software is subject to change without notice. Table of Contents ABOUT THESE REQUIREMENTS Changes Since Last Release iv When to Use these Requirements iv Completing the Checklist iv Master Disc Version Numbering System v PUBLISHER AND SOFTWARE INFORMATION FORM 1 MASTERING CHECKLIST 1.0 Basic Mastering Rules 2 2.0 CD-ROM Regulation 3 3.0 IDs for Master Disc Input on CD-ROM Generator 4 4.0 Special -

Jews Control U.S.A., Therefore the World – Is That a Good Thing?

Jews Control U.S.A., Therefore the World – Is That a Good Thing? By Chairman of the U.S. based Romanian National Vanguard©2007 www.ronatvan.com v. 1.6 1 INDEX 1. Are Jews satanic? 1.1 What The Talmud Rules About Christians 1.2 Foes Destroyed During the Purim Feast 1.3 The Shocking "Kol Nidre" Oath 1.4 The Bar Mitzvah - A Pledge to The Jewish Race 1.5 Jewish Genocide over Armenian People 1.6 The Satanic Bible 1.7 Other Examples 2. Are Jews the “Chosen People” or the real “Israel”? 2.1 Who are the “Chosen People”? 2.2 God & Jesus quotes about race mixing and globalization 3. Are they “eternally persecuted people”? 3.1 Crypto-Judaism 4. Is Judeo-Christianity a healthy “alliance”? 4.1 The “Jesus was a Jew” Hoax 4.2 The "Judeo - Christian" Hoax 4.3 Judaism's Secret Book - The Talmud 5. Are Christian sects Jewish creations? Are they affecting Christianity? 5.1 Biblical Quotes about the sects , the Jews and about the results of them working together. 6. “Anti-Semitism” shield & weapon is making Jews, Gods! 7. Is the “Holocaust” a dirty Jewish LIE? 7.1 The Famous 66 Questions & Answers about the Holocaust 8. Jews control “Anti-Hate”, “Human Rights” & Degraded organizations??? 8.1 Just a small part of the full list: CULTURAL/ETHNIC 8.2 "HATE", GENOCIDE, ETC. 8.3 POLITICS 8.4 WOMEN/FAMILY/SEX/GENDER ISSUES 8.5 LAW, RIGHTS GROUPS 8.6 UNIONS, OCCUPATION ORGANIZATIONS, ACADEMIA, ETC. 2 8.7 IMMIGRATION 9. Money Collecting, Israel Aids, Kosher Tax and other Money Related Methods 9.1 Forced payment 9.2 Israel “Aids” 9.3 Kosher Taxes 9.4 Other ways for Jews to make money 10. -

Viacom Media Networks

VIACOM MEDIA NETWORKS Viacom TAPE We manage the company’s physical and digital assets Research and organization Media LIBRARY and provide services to production and other groups who of material archives; data- Networks need access to library archives. Daily work flow includes entry of new material; tape circulation, cataloging, research projects, answering shipping materials between phones, record organization and management, tracking archives. and receiving shipments. 20% Learning the MTV Networks library archive database application. This is used for almost all library work 50% Library projects – Working on catalog records for a specific set of material submissions, creating manuals, etc. 30% Tape circulation – Learning to fill orders, refile tapes, and make shipments Nickelodeon OPERATIONS The Nickelodeon Global Operations group · Asset ingesting, tagging and supports several systems which facilitate cataloging of new assets as well as creation of creatives assets, consumer those from other systems such as products, marketing, advertising CRL campaigns as well as a host of digital · Enhancing metadata on existing media. The intern will work primarily with assets to improve search a group who support the digital asset · Taxonomy maintenance management systems and serve as · Maintaining the NickCentral help archivists of off-channel content created desk and responding to general site by Nickelodeon from the early 1990's to questions/issues present. · Work to streamline NickCentral Security Groupings · The digitizing of high value historical assets to insure their preservation and easy "find-ability" for years to come The digital asset management system and taxonomic structure is an ever- growing organism. We're looking for an analytical thinker that can participate in department discussions evaluating necessary top-down organizational changes as well as come up with creative solutions to problems. -

Sunday Morning, March 6

SUNDAY MORNING, MARCH 6 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sun (cc) Paid NBA Countdown NBA Basketball Chicago Bulls at Miami Heat. (Live) (cc) 2/KATU 2 2 (Live) (cc) Paid Tails of Abbygail CBS News Sunday Morning (N) (cc) Face the Nation College Basketball Kentucky at Tennessee. (Live) (cc) College Basketball 6/KOIN 6 6 (N) (cc) Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 7:00 AM (N) (cc) Meet the Press (N) (cc) NHL Hockey Philadelphia Flyers at New York Rangers. (Live) (cc) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) Betsy’s Kinder- Angelina Balle- Mister Rogers’ Curious George Thomas & Friends Bob the Builder Rick Steves’ Travels to the Nature Clash: Encounters of NOVA The Pluto Files. People’s 10/KOPB 10 10 garten rina: Next Neighborhood (TVY) (TVY) (TVY) Europe (TVG) Edge Bears and Wolves. (cc) (TVPG) opinions about Pluto. (TVPG) FOX News Sunday With Chris Wallace Good Day Oregon Sunday (N) Paid Memories of Me ★★ (‘88) Billy Crystal, Alan King. A young surgeon NASCAR Racing 12/KPTV 12 12 (cc) (TVPG) goes to L.A. to reconcile with his father. ‘PG-13’ (1:43) 5:00 Inspiration Ministry Camp- Turning Point Day of Discovery In Touch With Dr. Charles Stanley Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 meeting (Cont’d) (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) Spring Praise-A-Thon 24/KNMT 20 20 Paid Outlook Portland In Touch With Dr. -

Openbsd Gaming Resource

OPENBSD GAMING RESOURCE A continually updated resource for playing video games on OpenBSD. Mr. Satterly Updated August 7, 2021 P11U17A3B8 III Title: OpenBSD Gaming Resource Author: Mr. Satterly Publisher: Mr. Satterly Date: Updated August 7, 2021 Copyright: Creative Commons Zero 1.0 Universal Email: [email protected] Website: https://MrSatterly.com/ Contents 1 Introduction1 2 Ways to play the games2 2.1 Base system........................ 2 2.2 Ports/Editors........................ 3 2.3 Ports/Emulators...................... 3 Arcade emulation..................... 4 Computer emulation................... 4 Game console emulation................. 4 Operating system emulation .............. 7 2.4 Ports/Games........................ 8 Game engines....................... 8 Interactive fiction..................... 9 2.5 Ports/Math......................... 10 2.6 Ports/Net.......................... 10 2.7 Ports/Shells ........................ 12 2.8 Ports/WWW ........................ 12 3 Notable games 14 3.1 Free games ........................ 14 A-I.............................. 14 J-R.............................. 22 S-Z.............................. 26 3.2 Non-free games...................... 31 4 Getting the games 33 4.1 Games............................ 33 5 Former ways to play games 37 6 What next? 38 Appendices 39 A Clones, models, and variants 39 Index 51 IV 1 Introduction I use this document to help organize my thoughts, files, and links on how to play games on OpenBSD. It helps me to remember what I have gone through while finding new games. The biggest reason to read or at least skim this document is because how can you search for something you do not know exists? I will show you ways to play games, what free and non-free games are available, and give links to help you get started on downloading them. -

![[Catalog PDF] Manual Line Changes Nhl 14](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8833/catalog-pdf-manual-line-changes-nhl-14-888833.webp)

[Catalog PDF] Manual Line Changes Nhl 14

Manual Line Changes Nhl 14 Ps3 Download Manual Line Changes Nhl 14 Ps3 NHL 14 [PS3] - PS3. Trainers, astuces, triches et solutions pour Jeux PC, consoles et smartphones. Unlock the highest level of hockey aggression, speed and skill. NHL 14 brings together the best technology from EA SPORTS to deliver the most authentic hockey experience ever. Deliver hits with the cutting-edge NHL Collision Physics, built from FIFA's. NHL 14 for the Sony Playstation 3. Used game in great condition with a 90-day guarantee. DailyFaceoff line combinations - team lineups including power play lines and injuries are updated before and after game days based on real news delivered by team sources and beat reporters. Automated line changes based on calculations do not give you the team’s current lines – and that’s what you need for your fantasy lineups. EA Sports has announced that details of NHL 14 will be unveiled. Seeing as I have NHL 13 I can't imagine wanting to buy NHL 14 - but it'll be. In North America and on Wednesday in Europe (both XBox and PS3). It doesn't help that there's nothing in the manual to explain how to carry out faceoffs. Auto line changes and the idiot assistant coach. This problem seems to date back to time immemorial. Let’s say you have a bona fide top line center, rated at 87. Your second line center is an 82. Your third line center is an 80, and your fourth is a 75. NHL 14 PS3 Cheats. Gamerevolution Monday, September 16, 2013. -

Vintage Game Consoles: an INSIDE LOOK at APPLE, ATARI

Vintage Game Consoles Bound to Create You are a creator. Whatever your form of expression — photography, filmmaking, animation, games, audio, media communication, web design, or theatre — you simply want to create without limitation. Bound by nothing except your own creativity and determination. Focal Press can help. For over 75 years Focal has published books that support your creative goals. Our founder, Andor Kraszna-Krausz, established Focal in 1938 so you could have access to leading-edge expert knowledge, techniques, and tools that allow you to create without constraint. We strive to create exceptional, engaging, and practical content that helps you master your passion. Focal Press and you. Bound to create. We’d love to hear how we’ve helped you create. Share your experience: www.focalpress.com/boundtocreate Vintage Game Consoles AN INSIDE LOOK AT APPLE, ATARI, COMMODORE, NINTENDO, AND THE GREATEST GAMING PLATFORMS OF ALL TIME Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton First published 2014 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Road, Suite 402, Burlington, MA 01803 and by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2014 Taylor & Francis The right of Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

CHEAT CODES of the GODS: NARRATIVE and GREEK MYTHOLOGY in VIDEO GAMES by Eleanor Rose Sedgwick, B.A. a Thesis Submitted to the G

CHEAT CODES OF THE GODS: NARRATIVE AND GREEK MYTHOLOGY IN VIDEO GAMES by Eleanor Rose Sedgwick, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in Literature August 2021 Committee Members: Suparno Banerjee, Chair Anne Winchell Graeme Wend-Walker COPYRIGHT by Eleanor Rose Sedgwick 2021 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Eleanor Rose Sedgwick, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. DEDICATION I dedicate my thesis to my entire family, dogs and all, but primarily to my mother, who gave me the idea to research video games while sitting in a Thai food restaurant. Thank you, Mum, for encouraging me to write about the things I love most. I’d also like to dedicate my thesis to my dear group of friends that I met during my Master’s program, and plan to keep for the rest of my life. To Chelsi, Elisa, Hannah, Lindsey, Luise, Olivia, Sarah, and Tuesday—thank you for doing your part in keeping me sane throughout this project. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE SELF-PERCEPTION OF VIDEO GAME JOURNALISM: INTERVIEWS WITH GAMES WRITERS REGARDING THE STATE OF THE PROFESSION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Severin Justin Poirot Norman, Oklahoma 2019 THE SELF-PERCEPTION OF VIDEO GAME JOURNALISM: INTERVIEWS WITH GAMES WRITERS REGARDING THE STATE OF THE PROFESSION A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE GAYLORD COLLEGE OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION BY Dr. David Craig, Chair Dr. Eric Kramer Dr. Jill Edy Dr. Ralph Beliveau Dr. Julie Jones © Copyright by SEVERIN JUSTIN POIROT 2019 All Rights Reserved. iv Acknowledgments I’ve spent a lot of time and hand wringing wondering what I was going to say here and whom I was going to thank. First of all I’d like to thank my committee chair Dr. David Craig. Without his guidance, patience and prayers for my well-being I don’t know where I would be today. I’d like to also thank my other committee members: Dr. Eric Kramer, Dr. Julie Jones, Dr. Jill Edy, and Dr. Ralph Beliveau. I would also like to thank former member Dr. Namkee Park for making me feel normal for researching video games. Second I’d like to thank my colleagues at the University of Oklahoma who were there in the trenches with me for years: Phil Todd, David Ferman, Kenna Griffin, Anna Klueva, Christal Johnson, Jared Schroeder, Chad Nye, Katie Eaves, Erich Sommerfeldt, Aimei Yang, Josh Bentley, Tara Buehner, Yousuf Mohammad and Nur Uysal. I also want to extend a special thanks to Bryan Carr, who possibly is a bigger nerd than me and a great help to me in finishing this study. -

Spilling Hot Coffee? Grand Theft Auto As Contested Cultural Product

Aphra Kerr/IGTA book/2006 Spilling Hot Coffee? Grand Theft Auto as contested cultural product Dr. Aphra Kerr National University of Ireland Maynooth, Maynooth, Co. Kildare, Ireland. [email protected] Grand Theft Auto (GTA) games are highly successful, in terms of sales, and their content is part of an explicit business strategy which aims to exploit the latest technologies and platforms to develop content aimed at adult game players in certain markets. By all accounts this has been a highly successful strategy with the GTA franchise selling more than 30 million units across platforms by 2004, even before Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas (GTA SA) was launched in late 2004 (Take Two Interactive 2004). The latter was the top selling console game in the USA and in the top ten in the UK in 2005. At the same time the GTA series are arguably the most maligned of game products in many markets attracting much negative commentary and numerous legal actions in the USA. This chapter argues that the GTA case demonstrates a key tension within the cultural industries between the need to maximise sales globally and the need to conform to, or be seen to conform to, local distribution, social and moral systems. At the same time the story demonstrates that despite the widespread rhetoric of free trade and the dismantling of state sanctioned censorship systems in the USA, most parts of Europe and Australia, the censorship of cultural products continues and is perhaps a less overt, but nonetheless, highly political, socially negotiated and nationally specific process. GTA games are produced by a network of companies in the UK and in the USA. -

Vgarchive : My Video Game Collection 2021

VGArchive : My Video Game Collection 2021 Nintendo Entertainment System 8 Eyes USA | L Thinking Rabbit 1988 Adventures in the Magic Kingdom SCN | L Capcom 1990 Astérix FRA | L New Frontier / Bit Managers 1993 Astyanax USA | L Jaleco 1989 Batman – The Video Game EEC | L Sunsoft 1989 The Battle of Olympus NOE | CiB Infinity 1988 Bionic Commando EEC | L Capcom 1988 Blades of Steel SCN | L Konami 1988 Blue Shadow UKV | L Natsume 1990 Bubble Bobble UKV | CiB Taito 1987 Castlevania USA | L Konami 1986 Castlevania II: Simon's Quest EEC | L Konami 1987 Castlevania III: Dracula's Curse FRA | L Konami 1989 Chip 'n Dale – Rescue Rangers NOE | L Capcom 1990 Darkwing Duck NOE | L Capcom 1992 Donkey Kong Classics FRA | L Nintendo 1988 • Donkey Kong (1981) • Donkey Kong Jr. (1982) Double Dragon USA | L Technōs Japan 1988 Double Dragon II: The Revenge USA | L Technōs Japan 1989 Double Dribble EEC | L Konami 1987 Dragon Warrior USA | L Chunsoft 1986 Faxanadu FRA | L Nihon Falcom / Hudson Soft 1987 Final Fantasy III (UNLICENSED REPRODUCTION) USA | CiB Square 1990 The Flintstones: The Rescue of Dino & Hoppy SCN | B Taito 1991 Ghost'n Goblins EEC | L Capcom / Micronics 1986 The Goonies II NOE | L Konami 1987 Gremlins 2: The New Batch – The Video Game ITA | L Sunsoft 1990 High Speed ESP | L Rare 1991 IronSword – Wizards & Warriors II USA | L Zippo Games 1989 Ivan ”Ironman” Stewart's Super Off Road EEC | L Leland / Rare 1990 Journey to Silius EEC | L Sunsoft / Tokai Engineering 1990 Kings of the Beach USA | L EA / Konami 1990 Kirby's Adventure USA | L HAL Laboratory 1993 The Legend of Zelda FRA | L Nintendo 1986 Little Nemo – The Dream Master SCN | L Capcom 1990 Mike Tyson's Punch-Out!! EEC | L Nintendo 1987 Mission: Impossible USA | L Konami 1990 Monster in My Pocket NOE | L Team Murata Keikaku 1992 Ninja Gaiden II: The Dark Sword of Chaos USA | L Tecmo 1990 Rescue: The Embassy Mission EEC | L Infogrames Europe / Kemco 1989 Rygar EEC | L Tecmo 1987 Shadow Warriors FRA | L Tecmo 1988 The Simpsons: Bart vs.