Libro MISCELANEA 57 2Color.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perceptions of Dialect Standardness in Puerto Rican Spanish

Perceptions of Dialect Standardness in Puerto Rican Spanish Jonathan Roig Advisor: Jason Shaw Submitted to the faculty of the Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Yale University May 2018 Abstract Dialect perception studies have revealed that speakers tend to have false biases about their own dialect. I tested that claim with Puerto Rican Spanish speakers: do they perceive their dialect as a standard or non-standard one? To test this question, based on the dialect perception work of Niedzielski (1999), I created a survey in which speakers of Puerto Rican Spanish listen to sentences with a phonological phenomenon specific to their dialect, in this case a syllable- final substitution of [R] with [l]. They then must match the sounds they hear in each sentence to one on a six-point continuum spanning from [R] to [l]. One-third of participants are told that they are listening to a Puerto Rican Spanish speaker, one-third that they are listening to a speaker of Standard Spanish, and one-third are told nothing about the speaker. When asked to identify the sounds they hear, will participants choose sounds that are more similar to Puerto Rican Spanish or more similar to the standard variant? I predicted that Puerto Rican Spanish speakers would identify sounds as less standard when told the speaker was Puerto Rican, and more standard when told that the speaker is a Standard Spanish speaker, despite the fact that the speaker is the same Puerto Rican Spanish speaker in all scenarios. Some effect can be found when looking at differences by age and household income, but the results of the main effect were insignificant (p = 0.680) and were therefore inconclusive. -

Language in the USA

This page intentionally left blank Language in the USA This textbook provides a comprehensive survey of current language issues in the USA. Through a series of specially commissioned chapters by lead- ing scholars, it explores the nature of language variation in the United States and its social, historical, and political significance. Part 1, “American English,” explores the history and distinctiveness of American English, as well as looking at regional and social varieties, African American Vernacular English, and the Dictionary of American Regional English. Part 2, “Other language varieties,” looks at Creole and Native American languages, Spanish, American Sign Language, Asian American varieties, multilingualism, linguistic diversity, and English acquisition. Part 3, “The sociolinguistic situation,” includes chapters on attitudes to language, ideology and prejudice, language and education, adolescent language, slang, Hip Hop Nation Language, the language of cyberspace, doctor–patient communication, language and identity in liter- ature, and how language relates to gender and sexuality. It also explores recent issues such as the Ebonics controversy, the Bilingual Education debate, and the English-Only movement. Clear, accessible, and broad in its coverage, Language in the USA will be welcomed by students across the disciplines of English, Linguistics, Communication Studies, American Studies and Popular Culture, as well as anyone interested more generally in language and related issues. edward finegan is Professor of Linguistics and Law at the Uni- versity of Southern California. He has published articles in a variety of journals, and his previous books include Attitudes toward English Usage (1980), Sociolinguistic Perspectives on Register (co-edited with Douglas Biber, 1994), and Language: Its Structure and Use, 4th edn. -

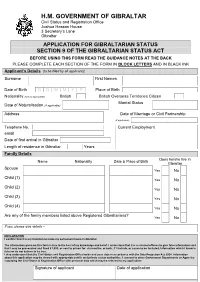

Application for Gibraltarian Status (Section 9)

H.M. GOVERNMENT OF GIBRALTAR Civil Status and Registration Office Joshua Hassan House 3 Secretary’s Lane Gibraltar APPLICATION FOR GIBRALTARIAN STATUS SECTION 9 OF THE GIBRALTARIAN STATUS ACT BEFORE USING THIS FORM READ THE GUIDANCE NOTES AT THE BACK PLEASE COMPLETE EACH SECTION OF THE FORM IN BLOCK LETTERS AND IN BLACK INK Applicant’s Details (to be filled by all applicants) Surname First Names Date of Birth D D M M Y Y Place of Birth Nationality (tick as appropriate) British British Overseas Territories Citizen Marital Status Date of Naturalisation (if applicable) Address Date of Marriage or Civil Partnership (if applicable) Telephone No. Current Employment email Date of first arrival in Gibraltar Length of residence in Gibraltar Years Family Details Does he/she live in Name Nationality Date & Place of Birth Gibraltar Spouse Yes No Child (1) Yes No Child (2) Yes No Child (3) Yes No Child (4) Yes No Are any of the family members listed above Registered Gibraltarians? Yes No If yes, please give details – DECLARATION I confirm that it is my intention to make my permanent home in Gibraltar. The information given on this form is true to the best of my knowledge and belief. I understand that it is a criminal offence to give false information and that I may be prosecuted and fined £1,000, or sent to prison for six months, or both, if I include, or cause to be included, information which I know is false or do not believe to be true. I also understand that the Civil Status and Registration Office holds and uses data in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2004. -

Excursion from Puerto Banús to Gibraltar by Jet

EXCURSION FROM PUERTO BANÚS TO GIBRALTAR BY JET SKI EXCURSION FROM PUERTO BANÚS TO GIBRALTAR Marbella Jet Center is pleased to present you an exciting excursion to discover Gibraltar. We propose a guided historical tour on a jet ski, along the historic and picturesque coast of Gibraltar, aimed at any jet ski lover interested in visiting Gibraltar. ENVIRONMENT Those who love jet skis who want to get away from the traffic or prefer an educational and stimulating experience can now enjoy a guided tour of the Gibraltar Coast, as is common in many Caribbean destinations. Historic, unspoiled and unadorned, what better way to see Gibraltar's mighty coastline than on a jet ski. YOUR EXPERIENCE When you arrive in Gibraltar, you will be taken to a meeting point in “Marina Bay” and after that you will be accompanied to the area where a briefing will take place in which you will be explained the safety rules to follow. GIBRALTAR Start & Finish at Marina Bay Snorkelling Rosia Bay Governor’s Beach & Gorham’s Cave Light House & Southern Defenses GIBRALTAR HISTORICAL PLACES DURING THE 2-HOUR TOUR BY JET SKI GIBRALTAR HISTORICAL PLACES DURING THE 2-HOUR TOUR BY JET SKI After the safety brief: Later peoples, notably the Moors and the Spanish, also established settlements on Bay of Gibraltar the shoreline during the Middle Ages and early modern period, including the Heading out to the center of the bay, tourists may have a chance to heavily fortified and highly strategic port at Gibraltar, which fell to England in spot the local pods of dolphins; they can also have a group photograph 1704. -

© 2017 Jeriel Melgares Sabillón

© 2017 Jeriel Melgares Sabillón EXPLORING THE CONFLUENCE OF CONFIANZA AND NATIONAL IDENTITY IN HONDURAN VOSEO: A SOCIOPRAGMATIC ANALYSIS BY JERIEL MELGARES SABILLÓN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Spanish in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2017 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Anna María Escobar, Co-Chair Professor Marina Terkourafi, Leiden University, Co-Director Professor Rakesh M. Bhatt Professor Eyamba Bokamba ii ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the dynamics of language variation and the process of language change from a Speaker-based approach (cp. Weinreich, Labov, & Herzog, 1968) through the analysis of a linguistic feature that has received much scholarly attention, namely, Spanish pronominal forms of address (see PRESEEA project), in an understudied variety: Honduran Spanish. Previous studies, as sparse as they are, have proposed that the system of singular forms in this variety comprises a set of three forms for familiar/informal address—vos, tú, and usted—and a sole polite/formal form, usted (Castro, 2000; Hernández Torres, 2013; Melgares, 2014). In order to empirically explore this system and detect any changes in progress within it, a model typical of address research in Spanish was adopted by examining pronoun use between interlocutors in specific types of relationships (e.g. parent- child or between friends). This investigation, however, takes this model further by also analyzing the attitudes Honduran speakers exhibit toward the forms in connection to their Honduran identity, while adopting Billig’s (1995) theory of ‘banal nationalism’—the (re)production of national identity through daily social practices—, and as a corollary, their spontaneous pronoun production, following Terkourafi’s (2001; 2004) frame-based approach. -

Coarticulation Between Aspirated-S and Voiceless Stops in Spanish: an Interdialectal Comparison

Coarticulation between Aspirated-s and Voiceless Stops in Spanish: An Interdialectal Comparison Francisco Torreira University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction In a large number of Spanish dialects, representing many of the world’s Spanish speakers, /s/ is reduced to or deleted entirely in word-internal preconsonantal position (e.g. /este/ → [ehte], este ‘this’), in word-final preconsonantal position (e.g. /las#toman/ → [lahtoman], las toman ‘they take them’), and/or in prepausal position (e.g. /komemos/ → [komemo(h)], comemos ‘we eat’). In those dialects considered the most phonologically innovative (such as the Spanish of Andalusia, Extremadura, Canary Islands, Hispanic Caribbean, Pacific coast of South America), /s/ debuccalization is also found in prevocalic environments word-finally (e.g. /las#alas/ → [lahala], las alas ‘the wings’) and even word-internally, this phenomenon being less common (e.g. /asi/ → [ahi], así ‘this way’). When considered in detail, the manifestations of aspirated-s can be very different depending on dialectal, phonetic and even sociolinguistic factors. Only in preconsonantal position, for example, different s-apirating dialects behave differently; and, even within each dialect and in preconsonantal position, different manifestations arise as a result of the consonant type following aspirated-s. In this study, I show that aspirated-s before voiceless stops has different phonetic characteristics in Western Andalusian, on one part, and Puerto Rican and Porteño Spanish on the other. While Western Andalusian exhibits consistent postaspiration and shorter or inexistent preaspiration, Puerto Rican and Porteño display consistent preaspiration but no postaspiration. Moreover, Andalusian Spanish voiceless stops in /hC/ clusters show a longer closure than voiceless stops in other conditions, a contrast that does not apply for Porteño and Puerto Rican Spanish. -

The Politics of Spanish in the World

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY Graduate Center 2014 The Politics of Spanish in the World José del Valle CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_pubs/84 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Part V Social and Political Contexts for Spanish 6241-0436-PV-032.indd 569 6/4/2014 10:09:40 PM 6241-0436-PV-032.indd 570 6/4/2014 10:09:40 PM 32 The Politics of Spanish in the World Laura Villa and José del Valle Introduction This chapter offers an overview of the spread of Spanish as a global language, focusing on the policies and institutions that have worked toward its promotion in the last two decades. The actions of institutions, as well as those of corporate and cultural agencies involved in this sort of language policy, are to be understood as part of a wider movement of internationalization of financial activities and political influence (Blommaert 2010; Coupland 2003, 2010; Fairclough 2006; Heller 2011b; Maurais and Morris 2003; Wright 2004). Our approach to globalization (Appadurai 2001; Steger 2003) emphasizes agency and the dominance of a few nations and economic groups within the neo-imperialist order of the global village (Del Valle 2011b; Hamel 2005). In line with this framework, our analysis of language and (the discourse of) globalization focuses on the geostrategic dimension of the politics of Spanish in the world (Del Valle 2007b, 2011a; Del Valle and Gabriel-Stheeman 2004; Mar-Molinero and Stewart 2006; Paffey 2012). -

Download This Report

Report GIBRALTAR A ROCK AND A HARDWARE PLACE As one of the four island iGaming hubs in Europe, Gibraltar’s tiny 6.8sq.km leaves a huge footprint in the gaming sector Gibraltar has long been associated with Today, Gibraltar is self-governing and for duty free cigarettes, booze and cheap the last 25 years has also been electrical goods, the wild Barbary economically self sufficient, although monkeys, border crossing traffic jams, the some powers such as the defence and Rock and online gaming. foreign relations remain the responsibility of the UK government. It is a key base for It’s an odd little territory which seems to the British Royal Navy due to its strategic continually hover between its Spanish location. and British roots and being only 6.8sq.km in size, it is crammed with almost 30,000 During World War II the area was Gibraltarians who have made this unique evacuated and the Rock was strengthened zone their home. as a fortress. After the 1968 referendum Spain severed its communication links Gibraltar is a British overseas peninsular that is located on the southern tip of Spain overlooking the African coastline as GIBRALTAR IS A the Atlantic Ocean meets the POPULAR PORT Mediterranean and the English meet the Spanish. Its position has caused a FOR TOURIST continuous struggle for power over the CRUISE SHIPS AND years particularly between Spain and the British who each want to control this ALSO ATTRACTS unique territory, which stands guard over the western Mediterranean via the Straits MANY VISITORS of Gibraltar. FROM SPAIN FOR Once ruled by Rome the area fell to the DAY VISITS EAGER Goths then the Moors. -

An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar

.............................................................................................................................................................................................................WORK IN PROGESS WORK IN PROGRESS TOMASZ PACIORKOWSKI DOI: 10.15290/CR.2018.23.4.05 Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar Abstract. Gibraltar, popularly known as “The Rock”, has been a British overseas territory since the Treaty of Utrecht was signed in 1713. The demographics of this unique colony reflect its turbulent past, with most of the population being of Spanish, Portuguese or Italian origin (Garcia 1994). Additionally, there are prominent minorities of Indians, Maltese, Moroccans and Jews, who have also continued to influence both the culture and the languages spoken in Gibraltar (Kellermann 2001). Despite its status as the only English overseas territory in continental Europe, Gibraltar has so far remained relatively neglected by scholars of sociolinguistics, new dialect formation, and World Englishes. The paper provides a summary of the current state of sociolinguistic research in Gibraltar, focusing on such aspects as identity formation, code-switching, language awareness, language attitudes, and norms. It also delineates a plan for further research on code-switching and national identity following the 2016 Brexit referendum. Keywords: Gibraltar, code-switching, sociolinguistics, New Englishes, dialect formation, Brexit. 1. Introduction Gibraltar is located on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula and measures just about 6 square kilometres. This small size, however, belies an extraordinarily complex political history and social fabric. In the Brexit referendum of 23rd of June 2016, the inhabitants of Gibraltar overwhelmingly expressed their willingness to continue belonging to the European Union, yet at the moment it appears that they will be forced to follow the decision of the British govern- ment and leave the EU (Garcia 2016). -

Gibraltar's Constitutional Future

RESEARCH PAPER 02/37 Gibraltar’s Constitutional 22 MAY 2002 Future “Our aims remain to agree proposals covering all outstanding issues, including those of co-operation and sovereignty. The guiding principle of those proposals is to build a secure, stable and prosperous future for Gibraltar and a modern sustainable status consistent with British and Spanish membership of the European Union and NATO. The proposals will rest on four important pillars: safeguarding Gibraltar's way of life; measures of practical co-operation underpinned by economic assistance to secure normalisation of relations with Spain and the EU; extended self-government; and sovereignty”. Peter Hain, HC Deb, 31 January 2002, c.137WH. In July 2001 the British and Spanish Governments embarked on a new round of negotiations under the auspices of the Brussels Process to resolve the sovereignty dispute over Gibraltar. They aim to reach agreement on all unresolved issues by the summer of 2002. The results will be put to a referendum in Gibraltar. The Government of Gibraltar has objected to the process and has rejected any arrangement involving shared sovereignty between Britain and Spain. Gibraltar is pressing for the right of self-determination with regard to its constitutional future. The Brussels Process covers a wide range of topics for discussion. This paper looks primarily at the sovereignty debate. It also considers how the Gibraltar issue has been dealt with at the United Nations. Vaughne Miller INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS AND DEFENCE SECTION HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers include: List of 15 most recent RPs 02/22 Social Indicators 10.04.02 02/23 The Patents Act 1977 (Amendment) (No. -

Thesis.Pdf (PDF, 297.83KB)

Cover Illustrations by the Author after two drawings by François Boucher. i Contents Note on Dates iii. Introduction 1. Chapter I - The Coming of the Dutchman: Prior’s Diplomatic Apprenticeship 7. Chapter II - ‘Mat’s Peace’, the betrayal of the Dutch, and the French friendship 17. Chapter III - The Treaty of Commerce and the Empire of Trade 33. Chapter IV - Matt, Harry, and the Idea of a Patriot King 47. Conclusion - ‘Britannia Rules the Waves’ – A seventy-year legacy 63. Bibliography 67. ii Note on Dates: The dates used in the following are those given in the sources from which each particular reference comes, and do not make any attempt to standardize on the basis of either the Old or New System. It should also be noted that whilst Englishmen used the Old System at home, it was common (and Matthew Prior is no exception) for them to use the New System when on the Continent. iii Introduction It is often the way with historical memory that the man seen by his contemporaries as an important powerbroker is remembered by posterity as little more than a minor figure. As is the case with many men of the late-Seventeenth- and early-Eighteenth-Centuries, Matthew Prior’s (1664-1721) is hardly a household name any longer. Yet in the minds of his contemporaries and in the political life of his country even after his death his importance was, and is, very clear. Since then he has been the subject of three full-length biographies, published in 1914, 1921, and 1939, all now out of print.1 Although of low birth Prior managed to attract the attention of wealthy patrons in both literary and diplomatic circles and was, despite his humble station, blessed with an education that was to be the foundation of his later success. -

Understanding the Tonada Cordobesa from an Acoustic

UNDERSTANDING THE TONADA CORDOBESA FROM AN ACOUSTIC, PERCEPTUAL AND SOCIOLINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVE by María Laura Lenardón B.A., TESOL, Universidad Nacional de Río Cuarto, 2000 M.A., Spanish Translation, Kent State University, 2003 M.A., Hispanic Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2017 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by María Laura Lenardón It was defended on April 21, 2017 and approved by Dr. Shelome Gooden, Associate Professor of Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh Dr. Susana de los Heros, Professor of Hispanic Studies, University of Rhode Island Dr. Matthew Kanwit, Assistant Professor of Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Scott F. Kiesling, Professor of Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by María Laura Lenardón 2017 iii UNDERSTANDING THE TONADA CORDOBESA FROM AN ACOUSTIC, PERCEPTUAL AND SOCIOLINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVE María Laura Lenardón, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2017 The goal of this dissertation is to gain a better understanding of a non-standard form of pretonic vowel lengthening or the tonada cordobesa, in Cordobese Spanish, an understudied dialect in Argentina. This phenomenon is analyzed in two different but complementary studies and perspectives, each of which contributes to a better understanding of the sociolinguistic factors that constrain its variation, as well as the social meanings of this feature in Argentina. Study 1 investigates whether position in the intonational phrase (IP), vowel concordance, and social class and gender condition pretonic vowel lengthening from informal conversations with native speakers (n=20).