The Case of Operation Anthropoid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Czechoslovak Exiles and Anti-Semitism in Occupied Europe During the Second World War

WALKING ON EGG-SHELLS: THE CZECHOSLOVAK EXILES AND ANTI-SEMITISM IN OCCUPIED EUROPE DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR JAN LÁNÍČEK In late June 1942, at the peak of the deportations of the Czech and Slovak Jews from the Protectorate and Slovakia to ghettos and death camps, Josef Kodíček addressed the issue of Nazi anti-Semitism over the air waves of the Czechoslovak BBC Service in London: “It is obvious that Nazi anti-Semitism which originally was only a coldly calculated weapon of agitation, has in the course of time become complete madness, an attempt to throw the guilt for all the unhappiness into which Hitler has led the world on to someone visible and powerless.”2 Wartime BBC broadcasts from Britain to occupied Europe should not be viewed as normal radio speeches commenting on events of the war.3 The radio waves were one of the “other” weapons of the war — a tactical propaganda weapon to support the ideology and politics of each side in the conflict, with the intention of influencing the population living under Nazi rule as well as in the Allied countries. Nazi anti-Jewish policies were an inseparable part of that conflict because the destruction of European Jewry was one of the main objectives of the Nazi political and military campaign.4 This, however, does not mean that the Allies ascribed the same importance to the persecution of Jews as did the Nazis and thus the BBC’s broadcasting of information about the massacres needs to be seen in relation to the propaganda aims of the 1 This article was written as part of the grant project GAČR 13–15989P “The Czechs, Slovaks and Jews: Together but Apart, 1938–1989.” An earlier version of this article was published as Jan Láníček, “The Czechoslovak Service of the BBC and the Jews during World War II,” in Yad Vashem Studies, Vol. -

The Statement

THE STATEMENT A Robert Lantos Production A Norman Jewison Film Written by Ronald Harwood Starring Michael Caine Tilda Swinton Jeremy Northam Based on the Novel by Brian Moore A Sony Pictures Classics Release 120 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS SHANNON TREUSCH MELODY KORENBROT CARMELO PIRRONE ERIN BRUCE ZIGGY KOZLOWSKI ANGELA GRESHAM 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, 550 MADISON AVENUE, SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 8TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 NEW YORK, NY 10022 PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com THE STATEMENT A ROBERT LANTOS PRODUCTION A NORMAN JEWISON FILM Directed by NORMAN JEWISON Produced by ROBERT LANTOS NORMAN JEWISON Screenplay by RONALD HARWOOD Based on the novel by BRIAN MOORE Director of Photography KEVIN JEWISON Production Designer JEAN RABASSE Edited by STEPHEN RIVKIN, A.C.E. ANDREW S. EISEN Music by NORMAND CORBEIL Costume Designer CARINE SARFATI Casting by NINA GOLD Co-Producers SANDRA CUNNINGHAM YANNICK BERNARD ROBYN SLOVO Executive Producers DAVID M. THOMPSON MARK MUSSELMAN JASON PIETTE MICHAEL COWAN Associate Producer JULIA ROSENBERG a SERENDIPITY POINT FILMS ODESSA FILMS COMPANY PICTURES co-production in association with ASTRAL MEDIA in association with TELEFILM CANADA in association with CORUS ENTERTAINMENT in association with MOVISION in association with SONY PICTURES -

ORTHODOX CHURCH on KAREL FARSKÝ. on the BATTLE of THEOLOGICAL ORIENTATION of the CZECHOSLOVAK CHURCH (HUSSITE) in the 1920S

Науковий вісник Ужгородського університету, серія «Історія», вип. 1 (42), 2020 УДК 94(437):281.96: 283/289 DOI: 10.24144/2523-4498.1(42).2020.202254 ORTHODOX CHURCH ON KAREL FARSKÝ. ON THE BATTLE OF THEOLOGICAL ORIENTATION OF THE CZECHOSLOVAK CHURCH (HUSSITE) IN THE 1920s Marek Pavel Doctor of Philosophy and Pedagogy; Professor; Professor Emeritus, Department of History, Faculty of Arts, Palacký University, Olomouc Email: [email protected] Scopus Author ID: 35178301400 http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7578-0783 One hundred years have passed since 1920 and the ‘Czech schism’, which is considered to be the foundation of the national Czechoslovak (Hussite) Church. It was created as a result of the reform movement of the Catholic clergy after the end of the Great War and the constitution of an independent Czechoslovak Republic on the ruins of the Habsburg Monarchy. The clergy, who were dissatisfied with the position of the Catholic Church in the empire and with some matters of the Church life and priests that had not been addressed in the long term, set out a programme for the reform of the Catholic Church in Czech lands. His demands were directed towards the autonomous position of the church, the introduction of the national language into services, the democratisation of the organisation of the church, and the reform of clerical celibacy. After the Roman Curia rejected the proposals, the reform movement’s radical wing decided to leave the church and form a national church. However, its establishment wasn’t sufficiently prepared and all fundamental issues of its existence, including its doctrine, were only solved after establishing the church. -

Ivo PEJČOCH, Fašismus V Českých Zemích. Fašistické A

CENTRAL EUROPEAN PAPERS 2014 / II / 1 203 Ivo PEJČOCH Fašismus v českých zemích. Fašistické a nacionálněsocialistické strany a hnutí v Čechách a na Moravě 1922–1945 Praha: Academia 2011, 864 pages ISBN 978-80-200-1919-6 Critical review of Ivo Pejčoch’s book “Fascism in Czech countries. Fascist and national-so- cialist parties and movements in Bohemia and Moravia 1922-1945” The peer reviewed book written by Ivo Pejčoch, a historian working in the Military Historical Institute, was published by the Academia publishing house in 2011. The central topic of the monograph is, as the name suggests, mapping of the Czech fascism from the time of its origination in early 1920s through the period of Munich agreement and World War II to the year 1945. As the author mentions in preface, he restricts himself to the activity of organizations of Czech nation and language, due to extent limitation. The topic of the book picks up the threads of the earlier published monographs by Tomáš Pasák and Milan Nakonečný. But unlike Pasák’s book “Czech fascism 1922-1945 and col- laboration”, Ivo Pejčoch does not analyze fascism and seek causes of sympathies of a num- ber of important personalities to that ideology. On the contrary, his book rather presents a summary of parties, small parties and movements related to fascism and National Social- ism. He deals in more detail with the major ones - i.e. the Národní obec fašistická (National Fascist Community) or Vlajka (The Flag), but also for example the Kuratorium pro výchovu mládeže (Board for Youth Education) that was not a political party but, under the guid- ance of Emanuel Moravec, aimed at spreading the Roman-Empire ideas and influencing a large group of primarily young Protectorate inhabitants. -

Dokumentation Das Letzte Duell. Die

Dokumentation Horst Mühleisen Das letzte Duell. Die Auseinandersetzungen zwischen Heydrich und Canaris wegen der Revision der »Zehn Gebote« I. Die Bedeutung der Dokumente Admiral Wilhelm Franz Canaris war als Chef der Abwehr eine der Schlüsselfigu- ren des Zweiten Weltkrieges. Rätselhaftes umgibt noch heute, mehr als fünfzig Jah- re nach seinem gewaltsamen Ende, diesen Mann. Für Erwin Lahousen, einen sei- ner engsten Mitarbeiter, war Canaris »eine Person des reinen Intellekts«1. Die Qua- lifikationsberichte über den Fähnrich z.S. im Jahre 1907 bis zum Kapitän z.S. im Jahre 1934 bestätigen dieses Urteü2. Viele Biographen versuchten, dieses abenteu- erliche und schillernde Leben zu beschreiben; nur wenigen ist es gelungen3. Un- 1 Vgl. die Aussage des Generalmajors a.D. Lahousen Edler von Vivremont (1897-1955), Dezember 1938 bis 31.7.1943 Chef der Abwehr-Abteilung II, über Canaris' Charakter am 30.11.1945, in: Der Prozeß gegen die Hauptkriegsverbrecher vor dem Internationalen Mi- litärgerichtshof (International Military Tribunal), Nürnberg, 14.11.1945-1.10.1946 (IMT), Bd 2, Nürnberg 1947, S. 489. Ders., Erinnerungsfragmente von Generalmajor a.D. Erwin Lahousen über das Amt Ausland/Abwehr (Canaris), abgeschlossen am 6.4.1948, in: Bun- desarchiv-Militärarchiv (BA-MA) Freiburg, MSg 1/2812, S. 64. Vgl. auch Ernst von Weiz- säcker, Erinnerungen, München, Leipzig, Freiburg i.Br. 1952, S. 175. 2 Vgl. Personalakte Wilhelm Canaris, in: BA-MA, Pers 6/105, fol. 1Γ-105Γ, teilweise ediert von Helmut Krausnick, Aus den Personalakten von Canaris, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte (VfZG), 10 (1962), S. 280-310. Eine weitere Personalakte, eine Nebenakte, in: BA-MA, Pers 6/2293. -

Palacky International Student Guide

International Student Guide www.study.upol.cz TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome from the Rector of Palacký University ................................................................... 4 PART 1: CZECH REPUBLIC, OLOMOUC, PALACKÝ UNIVERSITY ................................................. 5 Introduction – the Czech Republic ......................................................................................... 7 Culture shock .......................................................................................................................... 9 Czech Republic – blame it all on the culture ........................................................................ 10 Must watch and must read .................................................................................................. 12 Why Olomouc? .................................................................................................................... 13 Palacký University Olomouc ................................................................................................. 14 PART 2: PRACTICAL INFO BEFORE YOU ARRIVE ..................................................................... 17 Applications, deadlines, programmes .................................................................................. 19 Visas ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Health insurance ................................................................................................................. -

On the Orthodox Mission of the Serbian Bishop Dositheus (Vasić) in Czechoslovakia in 1920 – 1926

Štúdie, články | Studies, Articles Success, or Defeat? On the Orthodox Mission of the Serbian Bishop Dositheus (Vasić) in Czechoslovakia in 1920 – 1926 JURIJ DANILEC – PAVEL MAREK ABSTRACT: The formation of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918 created a new sit- uation for the nations still living in the Habsburg monarchy. Fundamental changes happened not only in terms of the constitutional law conditions, but also in all areas of the life of the society. The changes also affected the area of the church and religion. The democratic political regime guaranteed people freedom of religion. This fact is reflected in the reinforcement of secular tendencies, but at the same time there were changes and a revival of activities both inside established churches and in churches and religious societies which the political regime of the monarchy had suppressed. The inter-church transfer movement also affected the community professing the values of Eastern Christianity. The Orthodox movement had a spontaneous and unrestrained character. For this reason, the inexperienced state administration invited the Serbian Orthodox Church to help organize the Orthodox Church in Czechoslovakia, and so it sent a mission led by Dositheus (Vasić), the bishop of Niš, to the member country of the Little Entente. The bishop, who was mainly active on the territory of the Czech lands and in Subcarpathian Ruthenia, tried to establish the Orthodox faith in the Czech lands within the newly established National Church of Czechoslovakia (Hussite) and supported the emancipatory efforts of a group of Orthodox Czechs who had converted to Orthodoxy before World War I. In Subcarpathian Ruthenia, he sought to create a Carpathian Orthodox eparchy under the jurisdiction of the Serbian Orthodox Church. -

Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938–1948

21 Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938 –1948 LUCIE ZADRAILOVÁ AND MILAN PECH 332 Lucie Zadražilová and Milan Pech Lucie Zadražilová (Skřivánková) is a curator at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, while Milan Pech is a researcher at the Institute of Christian Art at Charles University in Prague. Teir text is a detailed archival study of the activities of two Czech art institutions, the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague and the Mánes Association of Fine Artists, during the Nazi Protectorate era and its immediate aftermath. Te larger aim is to reveal that Czech cultural life was hardly dormant during the Protectorate, and to trace how Czech institutions negotiated the limitations, dangers, and interferences presented by the occupation. Te Museum of Decorative Arts cautiously continued its independent activities and provided otherwise unattainable artistic information by keeping its library open. Te Mánes Association of Fine Artists trod a similarly-careful path of independence, managing to avoid hosting exhibitions by representatives of Fascism and surreptitiously presenting modern art under the cover of traditionally- themed exhibitions. Tis essay frst appeared in the collection Konec avantgardy? Od Mnichovské dohody ke komunistickému převratu (End of the Avant-Garde? From the Munich Agreement to the Communist Takeover) in 2011.1 (JO) Two Important Czech Institutions, 1938–1948 In the light of new information gained from archival sources and contemporaneous documents it is becoming ever clearer that the years of the Protectorate were far from a time of cultural vacuum. Credit for this is due to, among other things, the endeavours of many people to maintain at least a partial continuity in public services and to achieve as much as possible within the framework of the rules set by the Nazi occupiers. -

The Parish of Saint James

The Parish of Saint James 80 Hicksville Road Seaford, New York 11783 CELEBRATION OF EUCHARIST: MASSES: DAILY MASS: Monday through Friday: 8:00 AM All Civic Holidays: 9:00 AM only SUNDAY MASS SCHEDULE: Saturday Vigil: 4:00 PM The Clergy: Sunday:8:00 AM, Rev. John Derasmo, Pastor 10:00 AM [email protected] 12:00 PM Rev. Mariusz Gorazd, Associate Pastor Rev. Francis Sarpong, Associate Pastor SACRAMENT OF PENANCE: In the event of an emergency, please call Saturday: 3:00 PM – 3:45 PM or by 516-916-0959 to reach the priest on duty appointment with one of our priests. Deacon Rick Brunner Deacon Chris Daniello Deacon John Horn JULY 11, 2021 Office of Faith Formation - 796-2979 Lucy Creed, Director, Levels 1 through 6 Gina Drost, Coordinator, Levels 7 and 8 Parish Social Ministry—735-8690 Director of Music Ministry – 731-3710 ext. 149 Alfred Allongo Facility Manager Thomas Galvin – 516-731-3710 ext. 147 PARISH OFFICE RECEPTIONIST [email protected] PARISH OFFICE HOURS Phone: 731-3710/Fax: 731-4828 Monday - 9:00 am to 8:00 pm Tuesday - Friday: 9:00 am to 4:00 pm Closed between 12:00 pm to 1:00 pm Saturday: 9:00 am to 12 Noon Meetings with staff members should be by appointment. Visit us on the web: www.stjamesrcchurch.org Parish Mission Statement Saint James is a parish community, whose members are called through Baptism, to be intentional disciples. We are strengthened by the Eucharist and committed to serve God under the guidance of His Holy Spirit. -

SOBORNOST St

SOBORNOST St. Thomas the Apostle Orthodox Church (301) 638-5035 Church 4419 Leonardtown Road Waldorf, MD 20601 Rev. Father Joseph Edgington, Pastor (703) 532-8017 [email protected] Pani Stacey: [email protected] www.apostlethomas.org American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese ECUMENICAL PATRIARCHATE OF CONSTANTINOPLE Wed: Moleben to the Theotokos 6:00 AM Friday: Moleben to the Cross 6:00 AM Saturday: Confession 5:00 PM, Great Vespers 5:30 PM Sunday: Matins (Orthros) 8:45 AM Divine Liturgy 10:00 AM. September 4, 2016 – 11th Sunday After Pentecost New Hieromartyr Gorazd, Bishop of Prague O Lord, make this man also, who has been proclaimed a steward of the episcopal grace, to be an imitator of You, the true Shepherd, who laid down Your life for Your sheep… (Prayer of Consecration of a Bishop) On September 25, 1921, these words were prayed over Father Gorazd Pavlik as he was consecrated the Bishop of Moravia and Silesia. It is doubtful that anyone in attendance that day, including the new bishop, expected that he would be called upon to live that prayer in a literal way. Matthias Pavlik was born in 1879 in the Moravian town of Hrubavrbka in what would later become the Czech Republic. He was born into a Roman Catholic family, completed the Roman Catholic seminary in Olomouc and was ordained a priest. With the end of World War I and the formation of the new nation of Czechoslovakia from the ruins of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the laws requiring observance of the Catholic religion were loosened. Father Matthias, along with thousands of others left the Catholic Church with many seeking a home in the Orthodox Church, which in that region was then under the protection of the Orthodox Church of Serbia. -

GIPE-011912-05.Pdf

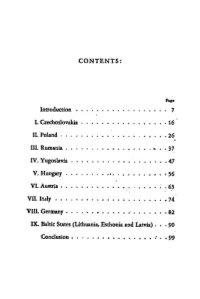

CONTENTS: Paco Introduction • • . 7 L Czechoslovakia . .J6 II. Poland .. • • 26 III. Rumania . ... • 37 IV. Yugoslavia . • • • •••• 47 V. Hungary ..• • • "'.. • "' • • • • . • , " l 56 VL Austtia ••. • • • • • ; • 6_5 VII. Italy ••• • ••• 74 VIII. Germany ••.•• •· • • • • 82 IX. Baltic States (Lithuania, Esthonia and latvia) . • • 90 Conclusion • • · . • • • • • • • , • • • • : • • 99 THE MILITARY J.MPORTANCE OF. CZECHOSLOVAKIA .IN EUROPE THE MILITARY IMPORTANCE OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA IN EUROPE COLONEL EMANUEL MORAVEC Profusor of tAe HigA Sclaool of War WitL. 8 Maps t 9 s a "Orl:.is" Printing and Pul:.lisl:.iog Co., Pregue l'BilfTBD BY «OABIB# l'B.A.GVlll li:II CZJtCHOBLOVA:&:IA. "If suc(.II!SS be achieved in uniting Austria with Germany, the collapse of Czechoslovakia will follow; Germany will then have common frontiers with Italy and Yugoslavia, and Italy will be strengthened against France." Ewald Banse in "Raum und Volk im Welt kriege", Edition of 1932. I BRIEF HISTORICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL OUTLINE The Rise of the Czechoslovak State After the defeat of the Central Powers at the end of October 1918 the Austro-Hungarian Empire fell asunder. The nations that had composed it either joined their kinsmen among the victorious Allied countries-Italy, Rumania and Yugoslavia--or formed new States. In this latter ma:nner arose Czechoslo vakia and Poland. Finally, there remained the racial· remnants of the old Monarchy-Austria with a Ger man population, and Hungary with a Magyar popu lation. The territories of the new Austria and Hun gary formed a central nationality zone in Central Europe touching the Italians on the West and the Ru manians on the East. North of this German-Magyar zone were the Slavonic nations forming the Republics· of Czechoslovakia and Poland. -

MASARYK-UNIVERSITÄT Reichsprotektorat Böhmen Und

MASARYK-UNIVERSITÄT PÄDAGOGISCHE FAKULTÄT Lehrstuhl für deutsche Sprache und Literatur Reichsprotektorat Böhmen und Mähren aus der historisch-rechtlichen Perspektive Bachelorarbeit Brünn 2019 Betreuer: Mgr. Pavel Váňa, Ph.D. Verfasser: JUDr. Jakub Valc "Ich erkläre, dass ich diese Abschlussarbeit (Bachelorarbeit) selbstständig ausgearbeitet habe, mithilfe der zitierten Quellen, anderer Informationen und Quellen im Einklang mit dem Disziplinarstatut für Studierende der Pädagogischen Fakultät der Masaryk-Universität und mit dem Gesetz Nr. 121/2000 Slg., über das Urheberrecht, über die mit dem Urheberrecht zusammenhängenden Rechte und über die Änderung einiger Gesetze (das Autorengesetz), in der Fassung der späteren Vorschriften." Brünn, 1. 3. 2019 ……………………………. JUDr. Jakub Valc 2 Danksagung Auf dieser Stelle möchte ich mich bei Herrn Mgr. Pavel Váňa, Ph.D., für seine wissenschaftliche Leitung und nützliche Ratschläge bedanken. Außerdem gehört mein Dank auch meiner Familie und allen Personen, die mich während des Studiums finanziell oder emotional unterstützt haben. 3 Abstract Diese Bachelorarbeit betrifft die Zeitperiode des sog. Protektorats Böhmen und Mähren, also die Zeit der Besatzung des ehemaligen Tschechoslowakischen Staates durch das Deutsche Reich. Innerhalb ihrer Bearbeitung beschäftige ich mich im Kontext mit den historischen Umständen nicht nur mit der Entstehung dieser Gebietseinheit, sondern auch mit ihrem staatspolitischen Aufbau und Regelung des öffentlichen Lebens. Dies hatte nämlich nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg eine große Wirkung auf die Formulierung des Rechtsdenkens und auf den Menschenrechtsschutz. Zuerst richte ich meine Aufmerksamkeit auf die Problematik des Aufstiegs des Nationalsozialismus in Deutschland und seine Expansion auf das tschechoslowakische Hoheitsgebiet als Folge des Münchner Abkommens. Dann werden die rechtliche Entstehung und das Funktionieren des Protektorats Böhmen und Mähren dargestellt, was besonders mit der Übernahme und Anwendung der Rassengesetzgebung zusammenhängt.