Taboos/Norms and Modern Science, and Possible Integration for Sustainable Management of the Flyingfish Resource of Orchid Island, Taiwan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. Area Post Office Name Zip Code Address Telephone No. Same Day

Zip No. Area Post Office Name Address Telephone No. Same Day Flight Cut Off Time * Code Pingtung Minsheng Rd. Post No. 250, Minsheng Rd., Pingtung 900-41, 1 Pingtung 900 (08)7323-310 (08)7330-222 11:30 Office Taiwan 2 Pingtung Pingtung Tancian Post Office 900 No. 350, Shengli Rd., Pingtung 900-68, Taiwan (08)7665-735 10:00 Pingtung Linsen Rd. Post 3 Pingtung 900 No. 30-5, Linsen Rd., Pingtung 900-47, Taiwan (08)7225-848 10:00 Office No. 3, Taitang St., Yisin Village, Pingtung 900- 4 Pingtung Pingtung Fusing Post Office 900 (08)7520-482 10:00 83, Taiwan Pingtung Beiping Rd. Post 5 Pingtung 900 No. 26, Beiping Rd., Pingtung 900-74, Taiwan (08)7326-608 10:00 Office No. 990, Guangdong Rd., Pingtung 900-66, 6 Pingtung Pingtung Chonglan Post Office 900 (08)7330-072 10:00 Taiwan 7 Pingtung Pingtung Dapu Post Office 900 No. 182-2, Minzu Rd., Pingtung 900-78, Taiwan (08)7326-609 10:00 No. 61-7, Minsheng Rd., Pingtung 900-49, 8 Pingtung Pingtung Gueilai Post Office 900 (08)7224-840 10:00 Taiwan 1 F, No. 57, Bangciou Rd., Pingtung 900-87, 9 Pingtung Pingtung Yong-an Post Office 900 (08)7535-942 10:00 Taiwan 10 Pingtung Pingtung Haifong Post Office 900 No. 36-4, Haifong St., Pingtung, 900-61, Taiwan (08)7367-224 Next-Day-Flight Service ** Pingtung Gongguan Post 11 Pingtung 900 No. 18, Longhua Rd., Pingtung 900-86, Taiwan (08)7522-521 10:00 Office Pingtung Jhongjheng Rd. Post No. 247, Jhongjheng Rd., Pingtung 900-74, 12 Pingtung 900 (08)7327-905 10:00 Office Taiwan Pingtung Guangdong Rd. -

No 17 Taiwan, Province of China

AN ANALYSIS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW, NATIONAL LEGISLATION, JUDGEMENTS, AND INSTITUTIONS AS THEY INTERRELATE WITH TERRITORIES AND AREAS CONSERVED BY INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND LOCAL COMMUNITIES REPORT NO. 17 TAIWAN 0 “Land is the foundation of the lives and cultures of Indigenous peoples all over the world… Without access to and respect for their rights over their lands, territories and natural resources, the survival of Indigenous peoples’ particular distinct cultures is threatened.” Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues Report on the Sixth Session 25 May 2007 Authored by: Dau-Jye Lu, Taiban Sasala and Chih-Liang Chao, in cooperation with the Tao Foundation Published by: Natural Justice in Bangalore and Kalpavriksh in Pune and Delhi Date: September 2012 Cover Photo: Ten oars plank boat. © Si Ngahephep, Tao Foundation 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: …........................................................................................................3 PART I: COUNTRY, COMMUNITIES AND ICCAs ........................................................... 3 1.1 Country (or subnational region) ................................................................................ 4 1.2 Communities & Environmental Change ..................................................................... 5 PART II: LAND, FRESHWATER AND MARINE LAWS & POLICIES ................................... 9 2.1 Land ............................................................................................................................. 10 2.2 Natural Resource Management .................................................................................. -

TAO RESIDENTS' PERCEPTIONS of SOCIAL and CULTRUAL IMPACTS of TOURISM in LAN-YU, TAIWAN Cheng-Hsuan Hsu Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 12-2006 TAO RESIDENTS' PERCEPTIONS OF SOCIAL AND CULTRUAL IMPACTS OF TOURISM IN LAN-YU, TAIWAN Cheng-hsuan Hsu Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Commons Recommended Citation Hsu, Cheng-hsuan, "TAO RESIDENTS' PERCEPTIONS OF SOCIAL AND CULTRUAL IMPACTS OF TOURISM IN LAN-YU, TAIWAN" (2006). All Theses. 47. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/47 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TAO RESIDENTS’ PERCEPTIONS OF SOCIAL AND CULTRUAL IMPACTS OF TOURISM IN LAN-YU, TAIWAN _________________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University _________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Park, Recreation, and Tourism Management _________________________________________________________ by Cheng-Hsuan Hsu December 2006 _________________________________________________________ Accepted by: Dr. Kenneth F. Backman, Committee Chair Dr. Sheila J. Backman Dr. Francis A. McGuire ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to investigate residents’ perceptions of the social and cultural impacts of tourism on Lan-Yu (Orchid Island). More specifically, this study examines Lan-Yu’s aboriginal residents’ (The Tao) perceptions of social and cultural impacts of tourism. Systematic sampling and a survey questionnaire procedure was employed in this study. After the factor analysis, three underlying dimensions were found when examining Tao residents’ perceptions of social and cultural impacts of tourism, and they were named: positive cultural effects, negative cultural effects, and negative social effects. -

Kenting Tours Kenting Tour

KENTING TOURS KENTING TOUR THEME PLAN / 4-PEOPLE TOUR PRICE(SHUTTLE SERVICE NOT INCLUDED) PAGE (Jan.)Rice Planting in the Organic Paddies of Long-Shui Community $300 / per 8 (May)Harvesting Rice in the Organic Paddies of Long-Shui Community $300 / per 9 (May - Oct.)Nighttime Harbourside Crab Explore $350 / per 11 KENTING TOUR (July - Aug.) $350 / per 12 (SEASONAL LIMITED) (Oct.)Buzzards over Lanren $1,000 / per 13 (Oct.)Buzzards over Lanren $750 / per 13 $999 / per (LUNCH INCLUDED) $699 / per Manzhou Memories of Wind - Explore The Old Trail of Manzhou Tea 15 $700 / per (LUNCH INCLUDED) 400 / per Travelling the Lanren River $400 / per 16 Tea Picking at Gangkou $250 / per 17 KENTING TOUR Deer by Sunrise $350 / per 18 (YEAR-ROUND) Daytime Deers Adventures $350 / per 19 Daytime Adventures $250 / per 20 Nighttime Adventures $250 / per 21 THEME PLAN PRICE (SHUTTLE SERVICE NOT INCLUDED) PRICE (SHUTTLE SERVICE INCLUDED) PAGE Discover Scuba Diving - $2,500 up / per 24 Scuba Diving - $3,500 / per 25 OCEAN Yacht Chartering Tour $58,000 / 40 people - 26 ATTRACTIONS Sailing Tour - $2,200 / minimum 4 people 28 GLORIA MANOR KENTING TOUR | 2 Cancellations Cancellation Time Cancellation Fee Cancellation Policy Remark 1 Hour before Tour Tour and Shuttle Fee Irresistible Factors : $50 / per You may need to pay the cancellation fee by 24 Hours before Tour Tour Fee cash. Irresistible Factors : Free 72 Hours before Tour $50 / per GLORIA MANOR KENTING TOUR | 3 KENTING’S ECOLOGY AND CULTURE Collaboration Kenting Shirding Near to GLORIA MANOR, the only workstation in Taiwan which dedicated to helping Formosan Sika deer (Cervus nippon taiouanus) quantity recover. -

No More Striving Alone, Together, We Will Define the Styles of This Generation

IPCF 2020 Issue magazine May 27 2020 May Issue 27 Issue May 2020 pimasaodan namen Life, with Indigenous Peoples with Indigenous Life, No more striving alone, together, we will define the styles of this generation. Words from Publisher Editorial ya mikepkep o vayo aka no adan a iweywawalam tiakahiwan kazakazash numa faqlhu a saran Cultural Diversity when Old Merges with New Novel Path to Cultural Awareness In recent years, there has been a great increase in indigenous isa Taiwaan mawalhnak a pruq manasha sa palhkakrikriw, peoples using creative and novel means to demonstrate numa sa parhaway shiminatantu malhkakrikriw, numa ya our traditional culture, as a result of cultural diversity. Take thuini a tiakahiwan a kazakazash ya mriqaz, mawalhnak a traditional totems as an example. Totemic symbols have, for pruq mathuaw maqarman tu shisasaz. hundreds of years, signified sacredness, collective ideology, and sense of identity. As we move into a new economic era, mawalhnak a pruq thau maqa mathuaw a numanuma, new meaning has been given to those totems. They are to demonstrate the uniqueness of each individual. I personally lhmazawaniza mafazaq ananak wa Thau, inangqtu think this is a good sign because it moves culture forwards. ananak uka sa aniamin numa. Ihai a munsai min’ananak a kazakazas masbut. kataunan a pruq mat mawalhnak a pruq, However, before starting to create, we need to have thorough lhmazawaniza kmilhim tiakahiwan kazakazash. mathuaw and precise understanding of our own culture. The young tmara a mafazaq ananak a, mamzai ananak ani inangqtu indigenous people living in urban areas want to learn more mafazaq, antu ukaiza sa Thau inangqtu painan. -

List of Insured Financial Institutions (PDF)

401 INSURED FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS 2021/5/31 39 Insured Domestic Banks 5 Sanchong City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 62 Hengshan District Farmers' Association of Hsinchu County 1 Bank of Taiwan 13 BNP Paribas 6 Banciao City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 63 Sinfong Township Farmers' Association of Hsinchu County 2 Land Bank of Taiwan 14 Standard Chartered Bank 7 Danshuei Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 64 Miaoli City Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 3 Taiwan Cooperative Bank 15 Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation 8 Shulin City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 65 Jhunan Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 4 First Commercial Bank 16 Credit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank 9 Yingge Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 66 Tongsiao Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 5 Hua Nan Commercial Bank 17 UBS AG 10 Sansia Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 67 Yuanli Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 6 Chang Hwa Commercial Bank 18 ING BANK, N. V. 11 Sinjhuang City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 68 Houlong Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 7 Citibank Taiwan 19 Australia and New Zealand Bank 12 Sijhih City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 69 Jhuolan Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 8 The Shanghai Commercial & Savings Bank 20 Wells Fargo Bank 13 Tucheng City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 70 Sihu Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 9 Taipei Fubon Commercial Bank 21 MUFG Bank 14 -

Genetic Diversity of Balanophora Fungosa and Its Conservation in Taiwan

Botanical Studies (2010) 51: 217-222. GENETIC DIVERSITY Genetic diversity of Balanophora fungosa and its conservation in Taiwan Shu-ChuanHSIAO*,Wei-TingHUANG,andMaw-SunLIN Department of Life Sciences, National Chung-Hsing University, 250 Kuo-Kuang Road, Taichung 40227, Taiwan (ReceivedOctober11,2007;AcceptedFebruary26,2010) ABSTRACT. Balanophora fungosa is a rare holoparasitic flowering plant in Taiwan, where it is restricted totheHengchunPeninsulainsouthernmostTaiwan,andOrchidIsland(LanyuinChinese),asmallvolcanic islandoffthesoutheasterncoastofTaiwan.Plantsfromthesetwoareasappearintwodifferentgroups basedonthecoloroftheinflorescence,i.e.,thoseofHengchunareyellow,buttheyarepinkishorangeto redonOrchidI.Thisstudyusedaninter-simplesequencerepeat(ISSR)molecularmarkerapproachandthe unweightedpairgroupmethodwitharithmeticmean(UPGMA)analysistoevaluategeneticvariationsamong populationsof B. fungosa.Theresultsshowedthatthetwogeographicalgroupsrepresentthesamespecies as indicated by a high Dice similarity value of 0.78. Populations from the two areas formed two well-defined clusters,asdidpopulationswithineacharea.Theresultsoftheanalysisofmolecularvariance(AMOVA) showedthatthecomponentsofvariationbetweengroups(31.35%),amongpopulationswithingroups (13.74%),andwithinpopulations(54.91%)weresignificant(p<0.001),indicatingthatvariationsamong individualswithinpopulationscontributedmosttothetotalgeneticvariance.Thepopulationsofthetwoareas werealsodifferentiatedwithgeneticdistancesrangingfrom0.44~0.53forpairedcomparisons.Therefore, werecommendthatprotectedareasbesetasideinbothareasfor -

Rethinking Indigenous People's Drinking Practices in Taiwan

Durham E-Theses Passage to Rights: Rethinking Indigenous People's Drinking Practices in Taiwan WU, YI-CHENG How to cite: WU, YI-CHENG (2021) Passage to Rights: Rethinking Indigenous People's Drinking Practices in Taiwan , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13958/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Passage to Rights: Rethinking Indigenous People’s Drinking Practices in Taiwan Yi-Cheng Wu Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Social Sciences and Health Department of Anthropology Durham University Abstract This thesis aims to explicate the meaning of indigenous people’s drinking practices and their relation to indigenous people’s contemporary living situations in settler-colonial Taiwan. ‘Problematic’ alcohol use has been co-opted into the diagnostic categories of mental disorders; meanwhile, the perception that indigenous people have a high prevalence of drinking nowadays means that government agencies continue to make efforts to reduce such ‘problems’. -

Download:Introduction of YUAN CHU

Introduction There are many ethnic groups living on the beautiful island of Taiwan. Among them are 430,000 indigenous status persons, which is about 1.9% of the total population. Although the number is relatively small, they perform superbly well in music, culture, and sports endeavors. The name "YUAN CHU MIN" in fact is a collective term. It includes Atayal, Saisiyat, Bunun, Tsou, Rukai, Paiwan, Puyuma, Amis, Yami, Thao, Kavalan, Truku and Sakizaya, to make up the thirteen indigenous tribes of Taiwan. Austronesia Language Family and Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Since the Paleolithic Age, the earliest inhabitants in Taiwan were the Austronesians. Academic research found that there were once more than 20 aboriginal tribes living in Taiwan and all belonged to the Austronesian family. Some scholars even concluded that Taiwan might be one of the original homelands of the Austronesians. Currently, twelve of the Austroneisan peoples are recognized by the government. They are Atayal, Saisiyat, Bunun, Tsou, Rukai, Paiwan, Puyuma, Amis, Yami, Thao, Kavalan, Truku and Sakizaya. Amis The area of Amis distribution stretches along plains around Mt. Chi-lai in NorthThe area of Amis distribution stretches along plains around Mt. Chi-lai in North Hualien, the long and narrow seacoast plains and the hilly lands in Taitung, Pintung and Hengtsuen Peninsula. At present, the population is about 158,000. The traditional social organization is based mainly on the matrilineal clans. After getting married, the male must move into the female’s residence. Family affairs including finance of the family are decided by the female householder. The affairs of marriage or the allocation of wealth should be Amis Distribution decided in a meeting hosted by the uncles of the female householder. -

The Role of Environmental Ngos in Tackling Environmental Problems in Taiwan Yttrium Sua Pomona College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2015 Bridging the Blue-Green Divide: The Role of Environmental NGOs in Tackling Environmental Problems in Taiwan Yttrium Sua Pomona College Recommended Citation Sua, Yttrium, "Bridging the Blue-Green Divide: The Role of Environmental NGOs in Tackling Environmental Problems in Taiwan" (2015). Pomona Senior Theses. Paper 133. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/133 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bridging the Blue-Green Divide: The Role of Environmental NGOs in Tackling Environmental Problems in Taiwan Yttrium Sua In partial fulfillment of a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Environmental Analysis, 2014-2015 academic year, Pomona College, Claremont, California Readers: Professor William Ascher & Professor Melinda Herrold-Menzies Acknowledgements Many thanks to… The Schulz Fund for Environmental Studies, funded by Jean Shulz, for funding my sophomore year summer research The Pomona College Summer Funding Internship Program for funding my junior year summer internship Professor William Ascher, Professor Melinda Herrold-Menzies, Professor Char Miller, and Professor Dru Gladney for the constant guidance and mentoring throughout the thesis writing process All my interviewees, -

Taiwan in Brief

MATSU TAIPEI ISLANDS KEELUNG ISLAND Taroko Music Festival Taiwan Hot Spring October KINMEN Season ISLANDS October-November This festival’s organisers wanted Taiwan TAOYUAN CITY GUISHAN to combine the visual splendor of The gradual arrival of winter formally ISLAND Taroko Gorge, arguably Taiwan’s announces that Taiwan’s peak hot most attractive scenic and natural spring season has begun. Hot spring YILAN CITY wonder, with the beauty of music. areas throughout the country hold in brief Over the years, different locations a series of events introducing their attractions Taiwan have been chosen for the music scenic beauty. During this period, TAICHUNG CITY Tourist Shuttle take performances, including the grassy hot spring areas throughout the Area Taroko passengers to the main area beside the Taroko National Park country hold a series of hot spring/ 36,000 sq km National Park tourist attractions in Taiwan. Visitor Center, the bed of the Liwu fine-cuisine events and pull together taiwantourbus.com.tw HUALIEN River near the Eternal Spring Shrine, hundreds of county Population taiwantrip.com.tw While outdoor events in Taiwan are not as large in scale or the grassy terraces at Buluowan, and municipal 23 million as well known internationally as the biggest happenings Taiwan East Coast and even a beach near the coastal companies, Taxis abroad – there are in fact plenty to chose from. Land Arts Festival Qingshui Cliff. introducing Languages Taxis here are well-marked the scenic Mandarin, Taiwanese, Hakka yellow vehicles easily recognised Taroko National Park, Hualien County beauty of the & Indigenous languages by visitors. The two largest ones There is something special about Trees covering the mountains and facebook.com/tarokomusic springs, the PENGHU Yushan ISLANDS National Park are Taiwan Taxi, often referred to being out in nature, whether it be for fields used to be an important cash local cultural Time zone as 55688, which is also their soaking in the scenery, watching birds crop for the Hakka tribe. -

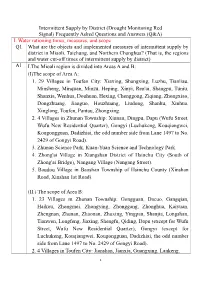

Intermittent Supply by District (Drought Monitoring Red Signal) Frequently Asked Questions and Answers (Q&A) I

Intermittent Supply by District (Drought Monitoring Red Signal) Frequently Asked Questions and Answers (Q&A) I. Water rationing times, measures, and scope Q1 What are the objects and implemented measures of intermittent supply by district in Miaoli, Taichung, and Northern Changhua? (That is, the regions and water cut-off times of intermittent supply by district) A1 I.The Mioali region is divided into Areas A and B: (I)The scope of Area A: 1. 29 Villages in Toufen City: Xiaxing, Shangxing, Luzhu, Tianliau, Minsheng, Minquan, Minzu, Heping, Xinyi, Ren'ai, Shangpu, Tuniu, Shanxia, Wenhua, Douhuan, Hexing, Chenggong, Ziqiang, Zhongxiao, Dongzhuang, Jianguo, Houzhuang, Liudong, Shanhu, Xinhua, Xinglong, Toufen, Pantau, Zhongxing. 2. 4 Villages in Zhunan Township: Xinnan, Dingpu, Dapu (Wufu Street, Wufu New Residential Quarter), Gongyi (Luchukeng, Kouqiangwei, Kougongguan, Dadizhiai, the odd number side from Lane 1497 to No. 2429 of Gongyi Road). 3. Zhunan Science Park, Kuan-Yuan Science and Technology Park. 4. Zhong'ai Village in Xiangshan District of Hsinchu City (South of Zhong'ai Bridge), Nangang Village (Nangang Street). 5. Baudou Village in Baoshan Township of Hsinchu County (Xinshan Road, Xinshan 1st Road). (II.) The scope of Area B: 1. 23 Villages in Zhunan Township: Gongguan, Dacuo, Gangqian, Haikou, Zhongmei, Zhongying, Zhonggang, Zhonghua, Kaiyuan, Zhengnan, Zhunan, Zhaonan, Zhuxing, Yingpan, Shanjia, Longshan, Tianwen, Longfeng, Jiaxing, Shengfu, Qiding, Dapu (except for Wufu Street, Wufu New Residential Quarter), Gongyi (except for Luchukeng, Kouqiangwei, Kougongguan, Dadizhiai, the odd number side from Lane 1497 to No. 2429 of Gongyi Road). 2. 4 Villages in Toufen City: Jianshan, Jianxia, Guangxing, Lankeng. 1 3. Zhunan Industrial Park, Toufen Industrial Park.