E-Learning in Endangered Language Documentation and Revitalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. Area Post Office Name Zip Code Address Telephone No. Same Day

Zip No. Area Post Office Name Address Telephone No. Same Day Flight Cut Off Time * Code Pingtung Minsheng Rd. Post No. 250, Minsheng Rd., Pingtung 900-41, 1 Pingtung 900 (08)7323-310 (08)7330-222 11:30 Office Taiwan 2 Pingtung Pingtung Tancian Post Office 900 No. 350, Shengli Rd., Pingtung 900-68, Taiwan (08)7665-735 10:00 Pingtung Linsen Rd. Post 3 Pingtung 900 No. 30-5, Linsen Rd., Pingtung 900-47, Taiwan (08)7225-848 10:00 Office No. 3, Taitang St., Yisin Village, Pingtung 900- 4 Pingtung Pingtung Fusing Post Office 900 (08)7520-482 10:00 83, Taiwan Pingtung Beiping Rd. Post 5 Pingtung 900 No. 26, Beiping Rd., Pingtung 900-74, Taiwan (08)7326-608 10:00 Office No. 990, Guangdong Rd., Pingtung 900-66, 6 Pingtung Pingtung Chonglan Post Office 900 (08)7330-072 10:00 Taiwan 7 Pingtung Pingtung Dapu Post Office 900 No. 182-2, Minzu Rd., Pingtung 900-78, Taiwan (08)7326-609 10:00 No. 61-7, Minsheng Rd., Pingtung 900-49, 8 Pingtung Pingtung Gueilai Post Office 900 (08)7224-840 10:00 Taiwan 1 F, No. 57, Bangciou Rd., Pingtung 900-87, 9 Pingtung Pingtung Yong-an Post Office 900 (08)7535-942 10:00 Taiwan 10 Pingtung Pingtung Haifong Post Office 900 No. 36-4, Haifong St., Pingtung, 900-61, Taiwan (08)7367-224 Next-Day-Flight Service ** Pingtung Gongguan Post 11 Pingtung 900 No. 18, Longhua Rd., Pingtung 900-86, Taiwan (08)7522-521 10:00 Office Pingtung Jhongjheng Rd. Post No. 247, Jhongjheng Rd., Pingtung 900-74, 12 Pingtung 900 (08)7327-905 10:00 Office Taiwan Pingtung Guangdong Rd. -

Axis Relationships in the Philippines – When Traditional Subgrouping Falls Short1 R. David Zorc <[email protected]> AB

Axis Relationships in the Philippines – When Traditional Subgrouping Falls Short1 R. David Zorc <[email protected]> ABSTRACT Most scholars seem to agree that the Malayo-Polynesian expansion left Taiwan around 3,000 BCE and virtually raced south through the Philippines in less than one millenium. From southern Mindanao migrations went westward through Borneo and on to Indonesia, Malaysia, and upwards into the Asian continent (“Malayo”-), and some others went south through Sulawesi also going eastward across the Pacific (-“Polynesian”)2. If this is the case, the Philippine languages are the “left behinds” allowing at least two more millennia for multiple interlanguage contacts within the archipelago. After two proposed major extinctions: archipelago-wide and the Greater Central Philippines (Blust 2019), inter-island associations followed the ebb and flow of dominance, expansion, resettlement, and trade. Little wonder then that “unique” lexemes found on Palawan can appear on Mindoro or Panay; developments throughout the east (Mindanao, the Visayas, and southern Luzon) can appear in Central Luzon, and an unidentified language with the shift of Philippine *R > y had some influence on Palawan and Panay. As early as 1972, while writing up my dissertation (Zorc 1975, then 1977), I found INNOVATIONS that did not belong to any specific subgroup, but had crossed linguistic boundaries to form an “axis” [my term, but related to German “SPRACHBUND”, “NETWORK” (Milroy 1985), “LINKAGE” 3 (Ross 1988. Pawley & Ross 1995)]. Normally, INNOVATIONS should be indicative of subgrouping. However, they can arise in an environment where different language communities develop close trade or societal ties. The word bakál ‘buy’ replaces PAN *bəlih and *mayád ‘good’ replaces PMP *pia in an upper loop from the Western Visayas, through Ilonggo/Hiligaynon, Masbatenyo, Central Sorsoganon, and 1 I am deeply indebted to April Almarines, Drs. -

Determiners, Nouns, Or What? Problems in the Analysis of Some Commonly Occurring Forms in Philippine Languages

Determiners, Nouns, or What? Problems in the Analysis of Some Commonly Occurring Forms in Philippine Languages Lawrence A. Reid Oceanic Linguistics, Vol. 41, No. 2. (Dec., 2002), pp. 295-309. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0029-8115%28200212%2941%3A2%3C295%3ADNOWPI%3E2.0.CO%3B2-T Oceanic Linguistics is currently published by University of Hawai'i Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/uhp.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sat Feb 16 23:46:32 2008 Determiners, Nouns, or What? Problems in the Analysis of Some Commonly Occurring Forms in Philippine Languages' Lawrence A. -

Kenting Tours Kenting Tour

KENTING TOURS KENTING TOUR THEME PLAN / 4-PEOPLE TOUR PRICE(SHUTTLE SERVICE NOT INCLUDED) PAGE (Jan.)Rice Planting in the Organic Paddies of Long-Shui Community $300 / per 8 (May)Harvesting Rice in the Organic Paddies of Long-Shui Community $300 / per 9 (May - Oct.)Nighttime Harbourside Crab Explore $350 / per 11 KENTING TOUR (July - Aug.) $350 / per 12 (SEASONAL LIMITED) (Oct.)Buzzards over Lanren $1,000 / per 13 (Oct.)Buzzards over Lanren $750 / per 13 $999 / per (LUNCH INCLUDED) $699 / per Manzhou Memories of Wind - Explore The Old Trail of Manzhou Tea 15 $700 / per (LUNCH INCLUDED) 400 / per Travelling the Lanren River $400 / per 16 Tea Picking at Gangkou $250 / per 17 KENTING TOUR Deer by Sunrise $350 / per 18 (YEAR-ROUND) Daytime Deers Adventures $350 / per 19 Daytime Adventures $250 / per 20 Nighttime Adventures $250 / per 21 THEME PLAN PRICE (SHUTTLE SERVICE NOT INCLUDED) PRICE (SHUTTLE SERVICE INCLUDED) PAGE Discover Scuba Diving - $2,500 up / per 24 Scuba Diving - $3,500 / per 25 OCEAN Yacht Chartering Tour $58,000 / 40 people - 26 ATTRACTIONS Sailing Tour - $2,200 / minimum 4 people 28 GLORIA MANOR KENTING TOUR | 2 Cancellations Cancellation Time Cancellation Fee Cancellation Policy Remark 1 Hour before Tour Tour and Shuttle Fee Irresistible Factors : $50 / per You may need to pay the cancellation fee by 24 Hours before Tour Tour Fee cash. Irresistible Factors : Free 72 Hours before Tour $50 / per GLORIA MANOR KENTING TOUR | 3 KENTING’S ECOLOGY AND CULTURE Collaboration Kenting Shirding Near to GLORIA MANOR, the only workstation in Taiwan which dedicated to helping Formosan Sika deer (Cervus nippon taiouanus) quantity recover. -

List of Insured Financial Institutions (PDF)

401 INSURED FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS 2021/5/31 39 Insured Domestic Banks 5 Sanchong City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 62 Hengshan District Farmers' Association of Hsinchu County 1 Bank of Taiwan 13 BNP Paribas 6 Banciao City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 63 Sinfong Township Farmers' Association of Hsinchu County 2 Land Bank of Taiwan 14 Standard Chartered Bank 7 Danshuei Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 64 Miaoli City Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 3 Taiwan Cooperative Bank 15 Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation 8 Shulin City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 65 Jhunan Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 4 First Commercial Bank 16 Credit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank 9 Yingge Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 66 Tongsiao Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 5 Hua Nan Commercial Bank 17 UBS AG 10 Sansia Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 67 Yuanli Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 6 Chang Hwa Commercial Bank 18 ING BANK, N. V. 11 Sinjhuang City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 68 Houlong Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 7 Citibank Taiwan 19 Australia and New Zealand Bank 12 Sijhih City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 69 Jhuolan Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 8 The Shanghai Commercial & Savings Bank 20 Wells Fargo Bank 13 Tucheng City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 70 Sihu Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 9 Taipei Fubon Commercial Bank 21 MUFG Bank 14 -

Contributors

iii Contributors ERIC ALBRIGHT received his MA in Applied Linguistics from GIAL (Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics, Texas) in 2000, and earlier, worked as a software developer. Joining SIL International, he worked among the Bidayuh of Sarawak, Malaysia from 2001-2003, advising them in the fields of literacy, orthography development and lexi- cography. In 2006, he co-founded Payap Language Software, part of the Linguistics Institute at Payap University in Thailand. I WAYAN ARKA is a Fellow in Linguistics at the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies (RSPAS) at The Australian National University. He received his PhD from Sydney University in 1999. He returned to Udayana University in Bali-Indonesia for three years before he moved again to Australia (in April 2001) to take up a fellowship at the RSPAS, ANU. Wayan’s interests are in descriptive, theoretical and typological aspects of Austronesian languages of Indonesia. His recent books published by Pacific Linguistics are Balinese Morphosyntax: A lexical-functional approach (2003) and The many faces of Austronesian voice systems: some new empirical studies, co-edited with Malcolm Ross (2005). Wayan is currently working on a number of projects including research on voice in the Austronesian languages of eastern Indonesia (funded by an NSF grant, 2006-2009, in collaboration with Matt Shibatani and Fay Wouk), and a large-scale machine-usable grammar, dictionary and corpus of Indonesian (funded by an ARC Discovery grant, 2008-10, in collaboration with Jane Simpon, Avery Andrews and Mary Dalrymple). He has done extensive fieldwork for his Rongga Documentation Project (funded by the ELDP, 2004-6), and organised capacity building programmes for language documentation, maintenance and revitalisation in Indonesia. -

Teaching and Learning an Endangered Austronesian Language in Taiwan

9 Teaching and Learning an Endangered Austronesian Language in Taiwan D. Victoria Rau°, Hui-Huan Ann Chang°, Yin-Sheng Tai°, Zhen-Yi Yang°, Yi-Hui Lin°, Chia-Chi Yang°, and Maa-Neu Dong† °Providence University, Taiwan †National Museum of Natural Science This paper provides a case study of the process of endangered language acquisition, which has not been well studied from the viewpoint of applied linguistics. It describes the con- text of teaching Chinese adult learners in Taiwan an endangered indigenous language, the teachers’ pedagogical approaches, the phonological and syntactic acquisition processes the learners were undergoing, and applications to other language documentation and revitaliza- tion programs. Both qualitative and quantitative methods were used to address the research questions.This study demonstrates cogently that language is a complex adaptive system. In phonological acquisition, the trill was the most difficult phoneme to learn. Systematic variations for the variables (ŋ) and (s) were found to be constrained by both markedness and interference. Furthermore, learners also tended to interpret Yami orthography based on their knowledge of English. In word order acquisition, learners performed much better than expected, partially because the present tense, coded by the SV word order, is the norm in Yami conversations. However, students still inaccurately associated word order with sen- tence type rather than with tense distinction. The Yami case provides an integrated model for endangered language documentation, revitalization and pedagogical research, which would be of interest to people working with other languages and the language documenta- tion field in general. 1. INTRODUCTION. There are several different approaches to the categorization of language endangerment. -

Morphology and Syntax of Gerunds in Truku Seediq : a Third Function of Austronesian “Voice” Morphology

MORPHOLOGY AND SYNTAX OF GERUNDS IN TRUKU SEEDIQ : A THIRD FUNCTION OF AUSTRONESIAN “VOICE” MORPHOLOGY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR IN PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS SUMMER 2017 By Mayumi Oiwa-Bungard Dissertation Committee: Robert Blust, chairperson Yuko Otsuka, chairperson Lyle Campbell Shinichiro Fukuda Li Jiang Dedicated to the memory of Yudaw Pisaw, a beloved friend ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my most profound gratitude to the hospitality and generosity of the many members of the Truku community in the Bsngan and the Qowgan villages that I crossed paths with over the years. I’d like to especially acknowledge my consultants, the late 田信德 (Tian Xin-de), 朱玉茹 (Zhu Yu-ru), 戴秋貴 (Dai Qiu-gui), and 林玉 夏 (Lin Yu-xia). Their dedication and passion for the language have been an endless source of inspiration to me. Pastor Dai and Ms. Lin also provided me with what I can call home away from home, and treated me like family. I am hugely indebted to my committee members. I would like to express special thanks to my two co-chairs and mentors, Dr. Robert Blust and Dr. Yuko Otsuka. Dr. Blust encouraged me to apply for the PhD program, when I was ready to leave academia after receiving my Master’s degree. If it wasn’t for the gentle push from such a prominent figure in the field, I would never have seen the potential in myself. -

Taiwan in Brief

MATSU TAIPEI ISLANDS KEELUNG ISLAND Taroko Music Festival Taiwan Hot Spring October KINMEN Season ISLANDS October-November This festival’s organisers wanted Taiwan TAOYUAN CITY GUISHAN to combine the visual splendor of The gradual arrival of winter formally ISLAND Taroko Gorge, arguably Taiwan’s announces that Taiwan’s peak hot most attractive scenic and natural spring season has begun. Hot spring YILAN CITY wonder, with the beauty of music. areas throughout the country hold in brief Over the years, different locations a series of events introducing their attractions Taiwan have been chosen for the music scenic beauty. During this period, TAICHUNG CITY Tourist Shuttle take performances, including the grassy hot spring areas throughout the Area Taroko passengers to the main area beside the Taroko National Park country hold a series of hot spring/ 36,000 sq km National Park tourist attractions in Taiwan. Visitor Center, the bed of the Liwu fine-cuisine events and pull together taiwantourbus.com.tw HUALIEN River near the Eternal Spring Shrine, hundreds of county Population taiwantrip.com.tw While outdoor events in Taiwan are not as large in scale or the grassy terraces at Buluowan, and municipal 23 million as well known internationally as the biggest happenings Taiwan East Coast and even a beach near the coastal companies, Taxis abroad – there are in fact plenty to chose from. Land Arts Festival Qingshui Cliff. introducing Languages Taxis here are well-marked the scenic Mandarin, Taiwanese, Hakka yellow vehicles easily recognised Taroko National Park, Hualien County beauty of the & Indigenous languages by visitors. The two largest ones There is something special about Trees covering the mountains and facebook.com/tarokomusic springs, the PENGHU Yushan ISLANDS National Park are Taiwan Taxi, often referred to being out in nature, whether it be for fields used to be an important cash local cultural Time zone as 55688, which is also their soaking in the scenery, watching birds crop for the Hakka tribe. -

A Brief Syntactic Typology of Philippine Languages

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa A Brief Syntactic Typology of Philippine Languages Lawrence A. Reid & Hsiu-chuan Liao University of Hawai‘i This paper is a brief statement of the typological characteristics of the syntactic structures of Philippine languages. It utilizes a lexicalist theoretical framework to provide comparability among the examples cited. The word order of both verbal and non-verbal predicational sentences is examined, with pronominal and non- pronominal complements, topicalization, and auxiliary verbs. Philippine languages are analyzed as morphologically ergative. The morphological criteria for determining the syntactic transitivity of verbal sentences is examined, concluding that verbal affixation alone is an insufficient criterion. Attention is paid to the notion of “focus”, with rejection of the concept of “voice” as an explanation for the phenomenon. The various forms of syntactically transitive verbs that have been described by others, for example, as signaling agreement with the Nominative NP, are here described as carrying semantic features, marking the manner of their instantiation with reference to the Nominative NP. The structure of noun phrases is examined. Morphological case marking of NPs by Determiners is claimed for Genitive, Locative, and for some languages, Oblique NPs, but it is claimed that for most languages, Nominative full NPs are case marked only by word order. Semantic agreement features distinguishing forms of Determiners for common vs. personal, definiteness, specificity, spatial reference, and plurality of their head nouns are described. Relative clause formation strategies are described. Most are head-initial, with gapping of the Nominative NP. -

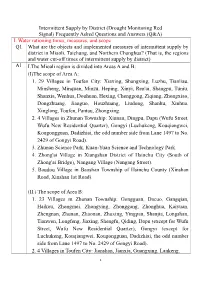

Intermittent Supply by District (Drought Monitoring Red Signal) Frequently Asked Questions and Answers (Q&A) I

Intermittent Supply by District (Drought Monitoring Red Signal) Frequently Asked Questions and Answers (Q&A) I. Water rationing times, measures, and scope Q1 What are the objects and implemented measures of intermittent supply by district in Miaoli, Taichung, and Northern Changhua? (That is, the regions and water cut-off times of intermittent supply by district) A1 I.The Mioali region is divided into Areas A and B: (I)The scope of Area A: 1. 29 Villages in Toufen City: Xiaxing, Shangxing, Luzhu, Tianliau, Minsheng, Minquan, Minzu, Heping, Xinyi, Ren'ai, Shangpu, Tuniu, Shanxia, Wenhua, Douhuan, Hexing, Chenggong, Ziqiang, Zhongxiao, Dongzhuang, Jianguo, Houzhuang, Liudong, Shanhu, Xinhua, Xinglong, Toufen, Pantau, Zhongxing. 2. 4 Villages in Zhunan Township: Xinnan, Dingpu, Dapu (Wufu Street, Wufu New Residential Quarter), Gongyi (Luchukeng, Kouqiangwei, Kougongguan, Dadizhiai, the odd number side from Lane 1497 to No. 2429 of Gongyi Road). 3. Zhunan Science Park, Kuan-Yuan Science and Technology Park. 4. Zhong'ai Village in Xiangshan District of Hsinchu City (South of Zhong'ai Bridge), Nangang Village (Nangang Street). 5. Baudou Village in Baoshan Township of Hsinchu County (Xinshan Road, Xinshan 1st Road). (II.) The scope of Area B: 1. 23 Villages in Zhunan Township: Gongguan, Dacuo, Gangqian, Haikou, Zhongmei, Zhongying, Zhonggang, Zhonghua, Kaiyuan, Zhengnan, Zhunan, Zhaonan, Zhuxing, Yingpan, Shanjia, Longshan, Tianwen, Longfeng, Jiaxing, Shengfu, Qiding, Dapu (except for Wufu Street, Wufu New Residential Quarter), Gongyi (except for Luchukeng, Kouqiangwei, Kougongguan, Dadizhiai, the odd number side from Lane 1497 to No. 2429 of Gongyi Road). 2. 4 Villages in Toufen City: Jianshan, Jianxia, Guangxing, Lankeng. 1 3. Zhunan Industrial Park, Toufen Industrial Park. -

The Handy Guide for Foreigners in Taiwan

The Handy Guide for Foreigners in Taiwan Research, Development and Evaluation Commission, Executive Yuan November 2010 A Note from the Editor Following centuries of ethnic cultural assimilation and development, today Taiwan has a population of about 23 million and an unique culture that is both rich and diverse. This is the only green island lying on the Tropic of Cancer, with a plethora of natural landscapes that includes mountains, hot springs, lakes, seas, as well as a richness of biological diversity that encompasses VSHFLHVRIEXWWHUÀLHVELUGVDQGRWKHUSODQWDQGDQLPDOOLIH$TXDUWHU of these are endemic species, such as the Formosan Landlocked Salmon (櫻 花鉤吻鮭), Formosan Black Bear (台灣黑熊), Swinhoe’s Pheasant (藍腹鷴), and Black-faced Spoonbill (黑面琵鷺), making Taiwan an important base for nature conservation. In addition to its cultural and ecological riches, Taiwan also enjoys comprehensive educational, medical, and transportation systems, along with a complete national infrastructure, advanced information technology and communication networks, and an electronics industry and related subcontracting industries that are among the cutting edge in the world. Taiwan is in the process of carrying out its first major county and city reorganization since 1949. This process encompasses changes in DGPLQLVWUDWLYHDUHDV$OORIWKHVHFKDQJHVZKLFKZLOOFUHDWHFLWLHVXQGHUWKH direct administration of the central government, will take effect on Dec. 25, 7RDYRLGFDXVLQJGLI¿FXOW\IRULWVUHDGHUVWKLV+DQGERRNFRQWDLQVERWK the pre- and post-reorganization maps. City and County Reorganization Old Name New Name (from Dec. 25, 2010) Taipei County Xinbei City Taichung County, Taichung City Taichung City Tainan County, Tainan City Tainan City Kaohsiung County, Kaohsiung City Kaohsiung City Essential Facts About Taiwan $UHD 36,000 square kilometers 3RSXODWLRQ $SSUR[LPDWHO\PLOOLRQ &DSLWDO Taipei City &XUUHQF\ New Taiwan Dollar (Yuan) /NT$ 1DWLRQDO'D\ Oct.