Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Missions and Film Jamie S

Missions and Film Jamie S. Scott e are all familiar with the phenomenon of the “Jesus” city children like the film’s abused New York newsboy, Little Wfilm, but various kinds of movies—some adapted from Joe. In Susan Rocks the Boat (1916; dir. Paul Powell) a society girl literature or life, some original in conception—have portrayed a discovers meaning in life after founding the Joan of Arc Mission, variety of Christian missions and missionaries. If “Jesus” films while a disgraced seminarian finds redemption serving in an give us different readings of the kerygmatic paradox of divine urban mission in The Waifs (1916; dir. Scott Sidney). New York’s incarnation, pictures about missions and missionaries explore the East Side mission anchors tales of betrayal and fidelity inTo Him entirely human question: Who is or is not the model Christian? That Hath (1918; dir. Oscar Apfel), and bankrolling a mission Silent movies featured various forms of evangelism, usually rekindles a wealthy couple’s weary marriage in Playthings of Pas- Protestant. The trope of evangelism continued in big-screen and sion (1919; dir. Wallace Worsley). Luckless lovers from different later made-for-television “talkies,” social strata find a fresh start together including musicals. Biographical at the End of the Trail mission in pictures and documentaries have Virtuous Sinners (1919; dir. Emmett depicted evangelists in feature films J. Flynn), and a Salvation Army mis- and television productions, and sion worker in New York’s Bowery recent years have seen the burgeon- district reconciles with the son of the ing of Christian cinema as a distinct wealthy businessman who stole her genre. -

Impassive Modernism in Arabic and Hebrew Literatures

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Against the Flow: Impassive Modernism in Arabic and Hebrew Literatures A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Shir Alon 2017 © Copyright by Shir Alon 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Against the Flow: Impassive Modernism in Arabic and Hebrew Literatures by Shir Alon Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Gil Hochberg, Co-Chair Professor Nouri Gana, Co-Chair Against the Flow: Impassive Modernism in Arabic and Hebrew Literatures elaborates two interventions in contemporary studies of Middle Eastern Literatures, Global Modernisms, and Comparative Literature: First, the dissertation elaborates a comparative framework to read twentieth century Arabic and Hebrew literatures side by side and in conversation, as two literary cultures sharing, beyond a contemporary reality of enmity and separation, a narrative of transition to modernity. The works analyzed in the dissertation, hailing from Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, Egypt, and Tunisia, emerge against the Hebrew and Arabic cultural and national renaissance movements, and the establishment of modern independent states in the Middle East. The dissertation stages encounters between Arabic and Hebrew literary works, exploring the ii parallel literary forms they develop in response to shared temporal narratives of a modernity outlined elsewhere and already, and in negotiation with Orientalist legacies. Secondly, the dissertation develops a generic-formal framework to address the proliferation of static and decadent texts emerging in a cultural landscape of national revival and its aftermaths, which I name impassive modernism. Viewed against modernism’s emphatic features, impassive modernism is characterized by affective and formal investment in stasis, immobility, or immutability: suspension in space or time and a desire for nonproductivity. -

The Greek and the Roman Novel. Parallel Readings

Leering for the Plot: Visual Curiosity in Apuleius and Others KIRK FREUDENBURG Yale University Winkler’s Auctor and Actor taught us to pay close attention to how listeners listen in Apuleius’s Metamorphoses, and how readers (featured as charac- ters) go about the act of interpreting, often badly, inside the novel’s many inset tales. Scenes of hermeneutical activity, he shows, have implications for readers on the outside looking in. My approach in this paper is largely in the same vein, but with a different emphasis. I want to watch the book’s inset watchers, not ‘rather than’ but ‘in addition to’ reading its readers. Expanding upon two recent articles by Niall Slater, I will focus on how their watching is figured, and what it does to them, by transfixing and transforming them in various regular (as we shall see) and suggestively ‘readable’ ways.1 My main point will concern the pleasures of the text that are produced and set out for critical inspection by the novel’s scenes of scopophilia, scenes that invite us to feast our eyes on characters happily abandoned to their desires. They draw us in to watch, and secretly enjoy the show. And in doing that they have the potential to tell us something not just about the bewitching powers of the book as a lush meadow of enticements, but about ourselves as stubborn mules who are easily enticed by its many pleasurable divertissements. Curi- osity is a problem in the book, something we load on Lucius’ back as his famous problem. That is clear enough. -

Women in Geoffrey Chaucer's the Canterbury Tales: Woman As A

1 Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Vladislava Vaněčková Women in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales: Woman as a Narrator, Woman in the Narrative Master's Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Doc. Milada Franková, Csc., M.A. 2007 2 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. ¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼.. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Medieval Society 7 2.1 Chaucer in His Age 9 2.2 Chaucer's Pilgrims 11 3. Woman as a Narrator: the Voiced Silence of the Female Pilgrims 15 3.1 The Second Nun 20 3.2 The Prioress 27 3.3 The Wife of Bath 34 4. Woman in Male Narratives: theIdeal, the Satire, and Nothing in Between 50 4.1 The Knight's Tale, the Franklin's Tale: the Courtly Ideal 51 4.1.1 The Knight's Tale 52 4.1.2 The Franklin's Tale 56 4.2 The Man of Law's Tale, the Clerk's Tale: the Christian Ideal 64 4.2.1 The Man of Law's Tale 66 4.2.2 The Clerk's Tale 70 4.3 The Miller's Tale, the Shipman's Tale: No Ideal at All 78 4.3.1 The Miller's Tale 80 4.3.2 The Shipman's Tale 86 5. Conclusion 95 6. Works Cited and Consulted 100 4 1. Introduction Geoffrey Chaucer is a major influential figure in the history of English literature. His The Canterbury Tales are read and reshaped to suit its modern audiences. -

A Tribute to Michael Curtiz 1973

Delta Kappa Alpha and the Division of Cinema of the University of Southern California present: tiz November-4 * Passage to Marseilles The Unsuspected Doctor X Mystery of the Wax Museum November 11 * Tenderloin 20,000 Years in Sing Sing Jimmy the Gent Angels with Dirty Faces November 18 * Virginia City Santa Fe Trail The Adventures of Robin Hood The Sea Hawk December 1 Casablanca t December 2 This is the Army Mission to Moscow Black Fury Yankee Doodle Dandy December 9 Mildred Pierce Life with Father Charge of the Light Brigade Dodge City December 16 Captain Blood The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex Night and Day I'll See You in My Dreams All performances will be held in room 108 of the Cinema Department. Matinees will start promptly at 1:00 p.m., evening shows at 7:30 p.m. A series of personal appearances by special guests is scheduled for 4:00 p.m. each Sunday. Because of limited seating capacity, admission will be on a first-come, first-served basis, with priority given to DKA members and USC cinema students. There is no admission charge. * If there are no conflicts in scheduling, these programs will be repeated in January. Dates will be announced. tThe gala performance of Casablanca will be held in room 133 of Founders Hall at 8:00 p.m., with special guests in attendance. Tickets for this event are free, but due to limited seating capacity, must be secured from the Cinema Department office (746-2235). A Mmt h"dific Uredrr by Arthur Knight This extended examination of the films of Michael Only in very recent years, with the abrupt demise of Curtiz is not only long overdue, but also altogether Hollywood's studio system, has it become possible to appropriate for a film school such as USC Cinema. -

Passion Love, Masculine Rivalry and Arabic Poetry in Mauritania Corinne Fortier

Passion Love, Masculine Rivalry and Arabic Poetry in Mauritania Corinne Fortier To cite this version: Corinne Fortier. Passion Love, Masculine Rivalry and Arabic Poetry in Mauritania. International Handbook of Love. Transcultural and transdisciplinary perspectives, pp.769 - 788, 2021, 10.1007/978- 3-030-45996-3_41. hal-03245591 HAL Id: hal-03245591 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03245591 Submitted on 25 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Chapter 41 Passion Love, Masculine Rivalry and Arabic Poetry in Mauritania Corinne Fortier Abstract Love was not born in the West during the twelfth century: the pre-Islamic Arabic poetry of the sixth century testifies to its existence in the ancient Arab world. These poems are well-known among Moors—the population in Mauritania who speaks an Arabic dialect called Ḥassāniyya—and inspire the local poetic forms. Unlike numerous traditions, poetic inspiration of Moorish poets is not spiritual but carnal because it takes root in the desire for a woman, who taste like Baudelaire’s Fleurs du Mal. Love poems in Mauritania are not the privilege of a handful, they are primaly composed with the aim of reaching the woman’s heart, like bedouin pre-islamic poetry. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

The Desired Woman

THE DESIRED WOMAN BY WILL N. HARBEN The Desired Woman PART I CHAPTER I Inside the bank that June morning the clerks and accountants on their high stools were bent over their ponderous ledgers, although it was several minutes before the opening hour. The gray-stone building was in Atlanta's most central part on a narrow street paved with asphalt which sloped down from one of the main thoroughfares to the section occupied by the old passenger depot, the railway warehouses, and hotels of various grades. Considerable noise, despite the closed windows and doors, came in from the outside. Locomotive bells slowly swung and clanged; steam was escaping; cabs, drays, and trucks rumbled and creaked along; there was a whir of a street-sweeping machine turning a corner and the shrill cries of newsboys selling the morning papers. Jarvis Saunders, member of the firm of Mostyn, Saunders & Co., bankers and brokers, came in; and, hanging his straw hat up, he seated himself at his desk, which the negro porter had put in order. "I say, Wright"—he addressed the bald, stocky, middle-aged man who, at the paying-teller's window, was sponging his fat fingers and counting and labeling packages of currency—"what is this about Mostyn feeling badly?" "So that's got out already?" Wright replied in surprise, as he approached and leaned on the rolling top of the desk. "He cautioned us all not to mention it. You know what a queer, sensitive sort of man he is where his health or business is concerned." "Oh, it is not public," Saunders replied. -

(Re-)Imagining the Nation: the Indian Historical Novel in English, 1900-2000

Negotiating History, (Re-)imagining the Nation: The Indian Historical Novel in English, 1900-2000 by Md. Rezaul Haque Master of Arts in Applied Linguistics (The University of Sydney, 2004) Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English, Creative Writing and Australian Studies Flinders University, South Australia June 2013 1 Table of Contents Introduction (6-45) Chapter 1 (46-92) Fiction, History and Nation in India Chapter 2 (93-137) The Emergence of Indian Historical Fiction: The Colonial Context Chapter 3 (138-162) Revivalist Historical Fiction 1: Padmini: An Indian Romance (1903) Chapter 4 (163-205) Revivalist Historical Fiction 2: Nur Jahan: The Romance of an Indian Queen (1909) Chapter 5 (206-241) Nationalist History Fiction 1: Kanthapura (1938) Chapter 6 (242-287) Nationalist History Fiction 2: The Lalu Trilogy (1939-42) Chapter 7 (288-351) Feminist History Fiction: Some Inner Fury (1955) Chapter 8 (352-391) Interventionist History Fiction: The Shadow Lines (1988) Chapter 9 (392-436) Revisionist Historical Fiction: The Devil’s Wind (1972) Conclusion (437-446) Bibliography (447-468) 2 Thesis Summary As the title of my project suggests, this thesis deals with Indian historical fiction in English. While the time frame in the title may lead one to expect that the present study will attempt a historical overview of the Indian historical novel written in English, that is not a primary concern. Rather, I pose two broad questions: the first asks, to what uses does Indian English fiction put the Indian past as it is remembered in both formal history and communal memory? The second question is perhaps a more important one so far as this project is concerned: why does the Indian English novel use the Indian past in the ways that it does? There is as a consequence an intention to move from the inner world of Indian historical fiction to the outer space of the socio-political reality from which the novel under consideration has been produced. -

Femme Fatale

the cinematic flâneur manifestations of modernity in the male protagonist of 1940s film noir Petra Désirée Nolan Submitted in Total Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2004 The School of Art History, Cinema, Classics and Archaeology The University of Melbourne Abstract The hardboiled hero is recognised as a central trope in the film noir cycle, and particularly in the ‘classic’ noir texts produced in Hollywood in the 1940s. Like the films themselves, this protagonist has largely been understood as an allegorical embodiment of a bleak post-World War Two mood of anxiety and disillusionment. Theorists have consistently attributed his pessimism, alienation, paranoia and fatalism to the concurrent American cultural climate. With its themes of murder, illicit desire, betrayal, obsession and moral dissolution, the noir canon also proves conducive to psychoanalytic interpretation. By oedipalising the noir hero and the cinematic text in which he is embedded, this approach at best has produced exemplary noir criticism, but at worst a tendency to universalise his trajectory. This thesis proposes a complementary and newly historicised critical paradigm with which to interpret the noir hero. Such an exegesis encompasses a number of social, aesthetic, demographic and political forces reaching back to the nineteenth century. This will reveal the centrality of modernity in shaping the noir hero’s ontology. The noir hero will also be connected to the flâneur, a figure who embodied the changes of modernity and who emerged in the mid-nineteenth century as both an historical entity and a critical metaphor for the new subject. As a rehistoricised approach will reveal, this nineteenth century—or classic—flâneur provides a potent template for the noir hero. -

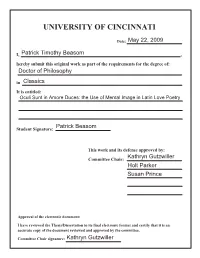

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 22, 2009 I, Patrick Timothy Beasom , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in Classics It is entitled: Oculi Sunt in Amore Duces: the Use of Mental Image in Latin Love Poetry Patrick Beasom Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Kathryn Gutzwiller Holt Parker Susan Prince Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Kathryn Gutzwiller Oculi Sunt in Amore Duces: The Use of Mental Image in Latin Love Poetry A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences by Patrick Timothy Beasom B.A., University of Richmond, 2002 M.A., University of Cincinnati, 2006 May 2009 Committee Chair: Kathryn Gutzwiller, Ph.D. Abstract Propertius tells us that the eyes are our guides in love. Both he and Ovid enjoin lovers to keep silent about their love affairs. I explore the ability of poetry to make our ears and our eyes guides, and, more importantly, to connect seeing and saying, videre and narrare. The ability of words to spur a reader or listener to form mental images was long recognized by Roman and Greek rhetoricians. This project takes stock for the first time of how poets, three Roman love poets, in this case, applied vivid description and other rhetorical devices to spur their readers to form mental images of the love they read. -

Women, Islam and Modernity

WOMEN, ISLAM AND MODERNITY Amina Abdullah Abu Shehab Submitted for award of Master of Philosophy, Department of Anthropology, London School of Economics, University of London July 1992 - 1 - UMI Number: U615401 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615401 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 .\-\5 % S cl ABSTRACT This thesis, based on written works, is concerned with the themes of women, religion and modernity in the Middle East. Modernity, which refers to modes of social life which emerged in Europe and became influential world wide, is being challenged by the Islamic revival. This movement, particularly, in its cultural and social aspects involves a rejection of modernist tendencies. Evidently, the topic of women is central to the antagonism between modernity and revived Islam, where the basic Islamic formulations concerning the family are re-emphasized. Part of the aim of this study is to focus on the problematic relation between Muslim women and modern ideas and practices and to understand the background of the current phenomenon of the "return” of women to Islam.