WORKS of ART in ITALY, Losses and Survival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Itinerár Výletu Švajčiarsko – Taliansko

ITINERÁR VÝLETU ŠVAJČIARSKO – TALIANSKO ODKIAĽ KAM A ZA KOĽKO Odkiaľ Kam Vzdialenosť (km) Čas (hodina) Nevädzová 3, 821 01 Bratislava Thermal Camping Brigerbad, 3900 981 11:00 Brig, Švajčiarsko Thermal Camping Brigerbad, 3900 Neue Kantonsstrasse 34 (jednosmerná) 00:40 Brig, Švajčiarsko 3929 Täsch (Parkhaus Zermatt) 68 (spiatočná) 01:30 Thermal Camping Brigerbad, 3900 Randa, Švajčiarsko 30 (jednosmerná) 00:30 Brig, Švajčiarsko 60 (spiatočná) 01:00 Thermal Camping Brigerbad, 3900 Gliserallee 13 3902 Glis, Švajčiarsko 6 (jednosmerná) 00:07 Brig, Švajčiarsko (návšteva mesta Bring) 12 (spiatočná) 00:14 Thermal Camping Brigerbad, 3900 Camping Orchidea, Via Repubblica 105 01:35 Brig, Švajčiarsko dell'Ossola 28831 Feriolo, Taliansko Camping Orchidea, Via Viale Sant'Anna, 1 28922 Verbania 6 (jednosmerná) 00:10 Repubblica dell'Ossola 28831 VB Taliansko 12 (spiatočná) 00:20 Feriolo, Taliansko Camping Orchidea, Via Loc. Mottarone Cima, 3, 28041 30 (jednosmerná) 00:40 Repubblica dell'Ossola 28831 Arona, Taliansko Mottarone 1491 60 (spiatočná) 01:20 Feriolo, Taliansko m Camping Orchidea, Via Via Aldo Ettore Kessler, 3, 37122 245 03:00 Repubblica dell'Ossola 28831 Verona VR, Taliansko Feriolo, Taliansko Via Aldo Ettore Kessler, 3, 37122 Camping Rocchetta - Località 239 03:45 Verona VR, Taliansko Campo di Sopra, 6, 32043 Cortina d'Ampezzo, Taliansko Camping Rocchetta - Località Lago di Sorrapis- SR48, 6, 32043 11(jednosmerná) 00:20 Campo di Sopra, 6, 32043 Cortina Cortina d'Ampezzo, Taliansko 22(spiatočná) 00:40 d'Ampezzo, Taliansko Camping Rocchetta - Località Tauern Spa Str. 1, 5710 Kaprun, 159 02:40 Campo di Sopra, 6, 32043 Cortina Zell am See, Rakúsko d'Ampezzo, Taliansko Tauern Spa Str. -

World War II Book.Indd

BOB HART WWllThe odyssey of a “Battling Buzzard” “Anything worth dying for ... is certainly worth living for.” –Joseph Heller, Catch-22 t was August 15, 1944, D-Day for Dragoon, the Allied invasion of southern France. Fifteen-hundred feet above a drop zone Ishrouded in fog, the wind buffeted Bob Hart’s helmet the instant before he plunged into the unknown at 4:35 a.m. “As soon as you got to the doorway all you saw was white. Most of us figured we were jumping over the Mediterranean. And for a split second all you could think was ‘I got 120 pounds of gear on me. What’s going to happen when I land?’ ” But now he was falling. “A thousand and one,” Hart said to himself as another paratrooper sprang from the doorway of the lumbering C-47. “A thousand and two. “A thousand and…” Hart’s body harness jerked taut reassuringly as the primary parachute billowed. Had he got past “three” he would have yanked the ripcord for the reserve chute bundled on his chest. The business about paratroopers yelling “Geronimo!” was mostly bravado that got old in a hurry after jump school. Paratroopers prepare for a practice jump from a C-47. Bob Hart collection 2 Bob Hart Descending in the eerie whiteness, the 20-year-old machine gunner from Tacoma fleetingly remembered how he and a buddy had signed up for the paratroopers 16 months earlier at Fort Lewis, reasoning they wouldn’t have to do much walking. Fat chance. After Hart landed hard in a farmer’s field in the foothills above the Côte d’Azur, he ended up tramping 50 miles through hostile countryside on an aching foot that turned out to be broken. -

Fascist Italy's Aerial Defenses in the Second World War

Fascist Italy's Aerial Defenses in the Second World War CLAUDIA BALDOLI ABSTRACT This article focuses on Fascist Italy's active air defenses during the Second World War. It analyzes a number of crucial factors: mass production of anti- aircraft weapons and fighters; detection of enemy aircraft by deploying radar; coordination between the Air Ministry and the other ministries involved, as well as between the Air Force and the other armed services. The relationship between the government and industrialists, as well as that between the regime and its German ally, are also crucial elements of the story. The article argues that the history of Italian air defenses reflected many of the failures of the Fascist regime itself. Mussolini's strategy forced Italy to assume military responsibilities and economic commitments which it could not hope to meet. Moreover, industrial self-interest and inter-service rivalry combined to inhibit even more the efforts of the regime to protect its population, maintain adequate armaments output, and compete in technical terms with the Allies. KEYWORDS air defenses; Air Ministry; anti-aircraft weapons; bombing; Fascist Italy; Germany; radar; Second World War ____________________________ Introduction The political and ideological role of Italian air power worked as a metaphor for the regime as a whole, as recent historiography has shown. The champions of aviation, including fighter pilots who pursued and shot down enemy planes, represented the anthropological revolution at the heart of the totalitarian experiment.1 As the Fascist regime had practiced terrorist bombing on the civilian populations of Ethiopian and Spanish towns and villages before the Second World War, the Italian political and military leadership, press, and industrialists were all aware of the potential role of air 1. -

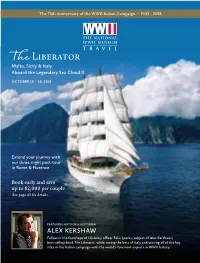

Alex Kershaw

The 75th Anniversary of the WWII Italian Campaign • 1943 - 2018 The Liberator Malta, Sicily & Italy Aboard the Legendary Sea Cloud II OCTOBER 19 – 28, 2018 Extend your journey with our three-night post-tour in Rome & Florence Book early and save up to $2,000 per couple See page 43 for details. FEATURING AUTHOR & HISTORIAN ALEX KERSHAW Follow in the footsteps of US Army officer Felix Sparks, subject of Alex Kershaw’s best-selling book The Liberator, while seeing the best of Italy and visiting all of the key sites in the Italian campaign with the world's foremost experts in WWII history. Dear friend of the Museum and fellow traveler, t is my great delight to invite you to travel with me and my esteemed colleagues from The National WWII Museum on an epic voyage of liberation and wonder – Ifrom the ancient harbor of Valetta, Malta, to the shores of Italy, and all the way to the gates of Rome. I have written about many extraordinary warriors but none who gave more than Felix Sparks of the 45th “Thunderbird” Infantry Division. He experienced the full horrors of the key battles in Italy–a land of “mountains, mules, and mud,” but also of unforgettable beauty. Sparks fought from the very first day that Americans landed in Europe on July 10, 1943, to the end of the war. He earned promotions first as commander of an infantry company and then an entire battalion through Italy, France, and Germany, to the hell of Dachau. His was a truly awesome odyssey: from the beaches of Sicily to the ancient ruins at Paestum near Salerno; along the jagged, mountainous spine of Italy to the Liri Valley, overlooked by the Abbey of Monte Cassino; to the caves of Anzio where he lost his entire company in what his German foes believed was the most savage combat of the war–worse even than Stalingrad. -

The Neonian Baptistery in Ravenna 359

Ritual and ReconstructedMeaning: The Neonian Baptisteryin Ravenna Annabel Jane Wharton The pre-modern work of art, which gained authority through its extension in ritual action, could function as a social integrator. This essay investigates the figural decoration of the Orthodox Baptistery in Ravenna, in an effort to explain certain features of the mosaic program. If the initiation ritual is reenacted and the civic centrality of the rite and its executant, the bishop, is restored, the apparent "icon- ographic mistakes" in the mosaics reveal themselves as signs of the mimetic re- sponsiveness of the icon. By acknowledging their unmediated character, it may be possible to re-empower both pre-modern images and our own interpretative strategy. The Neonian (or "Orthodox") Baptistery in Ravenna is the preciated, despite the sizable secondary literature generated most impressive baptistery to survive from the Early Chris- by the monument. Because the artistic achievement of the tian period (Figs. 1-5).1 It is a construction of the late fourth Neonian Baptistery lies in its eloquent embodiment of a or early fifth century, set to the north of the basilican ca- new participatory functioning of art, a deeper comprehen- thedral of Bishop Ursus (3897-96?) (Fig. 1).2 The whole of sion of the monument is possible only through a more thor- the ecclesiastical complex, including both the five-aisled ba- ough understanding of its liturgical and social context. The silica and the niched, octagonal baptistery, appears to have first section of this essay therefore attempts to reconstruct been modeled after a similar complex built in the late fourth the baptismal liturgy as it may have taken place in the century in Milan.3 Within two or three generations of its Neonian Baptistery. -

Dreamitaly0709:Layout 1

INSIDE: The Artistic Village of Dozza 3 Private Guides in Ravenna 5 Bicycling Through Ferrara 6 Where to Stay in Bologna 8 Giorgio Benni Giorgio giasco, flickr.com giasco, Basilica di San Vitale MAMbo SPECIAL REPORT: EMILIA-ROMAGNA Bologna: dream of City of Art ith its appetite for art, Bologna’s ® Wcontributions to the good life are more than gustatory. Though known as the “Red City” for its architecture and politics, I found a brilliant palette of museums, galleries, churches and markets, with mouth-watering visuals for every taste. ITALYVolume 8, Issue 6 www.dreamofitaly.com July/August 2009 City Museums For a splash of Ravcnna’s Ravishing Mosaics 14th-century sculp- ture start at the fter 15 centuries, Ravenna’s lumi- across the region of Emilia-Romagna. Fontana del Nettuno A nous mosaics still shine with the With only a day to explore, I’m grate- in Piazza Maggiore. golden brilliance of the empires that ful that local guide Verdiana Conti Gianbologna’s endowed them. These shimmering Baioni promises to weave art and bronze god — Fontana Nettuno sacred images reveal both familiar and history into every step. locals call him “the giant” — shares the unexpected chapters in Italian history water with dolphins, mermaids and while affirming an artistic climate that We meet at San Apollinaire Nuovo on cherubs. Close by, Palazzo Comunale’s thrives today. Via di Roma. A soaring upper floors contain the Collezioni basilica, its narrow side Comunale d’Arte, which includes opu- Ravenna attracted con- aisles open to a broad lent period rooms and works from the querors from the north nave where three tiers 14th through 19th centuries. -

Military Historical Society of Minnesota

The 34th “Red Bull” Infantry Division 1917-2010 Organization and World War One The 34th Infantry Division was created from National Guard troops of Minnesota, Iowa, the Dakotas and Nebraska in late summer 1917, four months after the US entered World War One. Training was conducted at Camp Cody, near Deming, New Mexico (pop. 3,000). Dusty wind squalls swirled daily through the area, giving the new division a nickname: the “Sandstorm Division.” As the men arrived at Camp Cody other enlistees from the Midwest and Southwest joined them. Many of the Guardsmen had been together a year earlier at Camp Llano Grande, near Mercedes, Texas, on the Mexican border. Training went well, and the officers and men waited anxiously throughout the long fall and winter of 1917-18 for orders to ship for France. Their anticipation turned to anger and frustration, however, when word was received that spring that the 34th had been chosen to become a replacement division. Companies, batteries and regiments, which had developed esprit de corps and cohesion, were broken up, and within two months nearly all personnel were reassigned to other commands in France. Reduced to a skeleton of cadre NCOs and officers, the 34th remained at Camp Cody just long enough for new draftees to refill its ranks. The reconstituted division then went to France, but by the time it arrived in October 1918, it was too late to see action. The war ended the following month. Between Wars After World War One, the 34th was reorganized with National Guardsmen from Iowa, Minnesota and South Dakota. -

Graduatoria Definitiva Mobilità Personale Educativo 2015-2016

GRADUATORIA DEFINITIVA MOBILITÀ PERSONALE EDUCATIVO A .S. 2015/2016 TRASFERIMENTI PROVINCIALI xxx PUNTEGGIO PUNTEGGIO PER DATA DI ORDINE DI PER ALTRI COMUNE COGNOME E NOME TITOLARITA ’ PRECEDENZA SEDI RICHIESTE NASCITA PREFERENZA COMUNI RICONGIUNGIMENTO RICCI ANTONIO 01/01/1962 ARPINO 173 IPSSAR Cassino - IPSSEOA Fiuggi ANAGNI PARSENA AURELIO 21/04/1959 154 IPSSEOA Fiuggi IPSSAR “M. BUONARROTI” – FIUGGI LANZA MAURO 05/12/1970 ARPINO 118 .I.S. “S. Benedetto” Cassino ARPINO GIANFRANCO 25/12/1960 ARPINO I.I.S. “S. Benedetto” Cassino - IPSSEOA Fiuggi 111 ANAGNI IPSSEOA Fiuggi BIANCHI ANTONIO 24/06/1960 101 107 ARPINO IPSSEOA Fiuggi - I.I.S. “S. Benedetto” Cassino GERMANI ORAZIO 20/09/1958 98 104 SACCO FERNANDA 01/08/1958 ANAGNI IPSSAR CASSINO - IPSSEOA FIUGGI 94 100 MORMILE RICCARDO 11/09/1959 ARPINO 90 IPSSAR “M. BUONARROTI” – FIUGGI IPSSEOA FIUGGI MANNI FERNANDO 11/06/1952 ANAGNI 70 Convitto Nazionale “Tulliano “ di Arpino DE ARCANGELIS MARCO 20/10/1962 ANAGNI 61 67 PROVINCIA DI Convitto Naz. Regina Margherita – Anagni D’A MICO MANUELA 20/11/1974 FROSINONE 48 54 - IPSSEOA Fiuggi - I.I.S. “S. Benedetto” Cassino IPSSEOA Fiuggi COPPOLA GIOVANNA 11/09/1956 ANAGNI 46 52 1 GRADUATORIA DEFINITIVA MOBILITÀ PERSONALE EDUCATIVO A .S. 2015/2016 TRASFERIMENTI INTERPROVINCIALI xxx PUNTEGGIO PUNTEGGIO PER DATA DI ORDINE DI COGNOME E NOME TITOLARITA ’ PER ALTRI COMUNE SEDI RICHIESTE NASCITA PREFERENZA COMUNI RICONGIUNGIMENTO Convitto “A. di Savoia Ipssar – Fiuggi – TURRIZIANI ERNESTO 31/01/1959 Duca d’Aosta”Tivoli Conv. Naz. “Reg. Margherita” – Anagni (RM) 151 157 I.C. “M.T. Cicerone” Arpino – Iis San Benedetto - Cassino Iis San Benedetto – Cassino Convitto Nazionale AVELLINO – CASERTA Convitto Annesso Cassino DE MARCO ROSARIO 02/07/1972 “Cicognini” - Prato - FROSINONE Convitto Tulliano – Arpino Ipsseoa “Buonarroti” – Fiuggi 63 Convitto “Regina Margherita” - Anagni Convitto “V. -

Plio-Pleistocene Proboscidea and Lower Palaeolithic Bone Industry of Southern Latium (Italy)

Plio-Pleistocene Proboscidea and Lower Palaeolithic bone industry of southern Latium (Italy) I. Biddittu1, P. Celletti2 1Museo Preistorico di Pofi, Frosinone, Italia, Istituto Italiano di Paleontologia Umana, Roma, Italy - [email protected] 2Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza”, Rome, Italy [email protected] SUMMARY: Elephant remains were first reported from the Valle Latina, in inner southern Latium, in 1864, by O.G. Costa. Since, they have been discovered at some 20 sites, ranging in age from the Middle Villafranchian (Costa S. Giacomo, with both Anancus arvernensis and Mammuthus (Archidiskodon) meri- dionalis), to the Late Pleistocene (S. Anna near Veroli, with Mammuthus primigenius). Most of the relevant faunal record, however, is of Middle Pleistocene age, and is characterised by Elephas antiquus. This species was discovered, most notably, at several archaeological sites, in association with Acheulean industry, starting with Fontana Ranuccio near Anagni, which is dated to c. 450 ka bp by K/Ar. At such sites, bones of Elephas antiquus were sometimes knapped to produce bone tools, including bone handaxes. 1. PROBOSCIDEA IN THE VALLE LATINA Stephanorhinus cfr. S. etruscus, Equus stenon- is, Pseudodama cfr P. lyra, Eucladoceros cfr. E. The quaternary deposits in the Valle Latina tegulensis, Leptobos sp., Gazella borbonica, are rich in faunal finds. These include frequent Gazellospira torticornis, Canis cfr. C. etruscus, elephant bones that have been the subject of Vulpes cfr. V. alopecoides, Hyaenidae gen. sp. scientific interest since the second half of the indet. and Hystrix cfr. H. refossa (Cassoli & nineteenth century. Segre Naldini 1993; Palombo et al. -

Servite Order 1 Servite Order

Servite Order 1 Servite Order Order of the Servants of Mary Abbreviation OSM Formation 1233 Type Mendicant order Marian devotional society Headquarters Santissima Annunziata Basilica, Florence, Italy Website [1] The Servite Order is one of the five original Catholic mendicant orders. Its objects are the sanctification of its members, preaching the Gospel, and the propagation of devotion to the Mother of God, with special reference to her sorrows. The members of the Order use O.S.M. (for Ordo Servorum Beatae Mariae Virginis) as their post-nominal letters. The male members are known as Servite Friars or Servants of Mary. The Order of Servants of Mary (The Servites) is a religious family that embraces a membership of friars (priests and brothers), contemplative nuns, a congregation of active sisters and lay groups. History Foundation The Servites lead a community life in the tradition of the mendicant orders (such as the Dominicans and Franciscans). The Servite Order was founded in 1233 AD, when a group of cloth merchants of Florence, Italy, left their city, families and professions to retire outside the city on a mountain known as Monte Senario for a life of poverty and penance. These men are known as the Seven Holy Founders; they were canonized by Pope Leo XIII in 1888.[2] These seven were: Buonfiglio dei Monaldi (Bonfilius), Giovanni di Buonagiunta (Bonajuncta), Amadeus of the Amidei (Bartolomeus), Ricovero dei Lippi-Ugguccioni (Hugh), Benedetto dell' Antella (Manettus), Gherardino di Sostegno (Sostene), and Alessio de' Falconieri (Alexius). They belonged to seven patrician families of that city. As a reflection of the penitential spirit of the times, it had been the custom of these men to meet regularly as members of a religious society established in honor of Mary, the Amadeus of the Amidei (d. -

The History of Painting in Italy, Vol. V

The History Of Painting In Italy, Vol. V By Luigi Antonio Lanzi HISTORY OF PAINTING IN UPPER ITALY. BOOK III. BOLOGNESE SCHOOL. During the progress of the present work, it has been observed that the fame of the art, in common with that of letters and of arms, has been transferred from place to place; and that wherever it fixed its seat, its influence tended to the perfection of some branch of painting, which by preceding artists had been less studied, or less understood. Towards the close of the sixteenth century, indeed, there seemed not to be left in nature, any kind of beauty, in its outward forms or aspect, that had not been admired and represented by some great master; insomuch that the artist, however ambitious, was compelled, as an imitator of nature, to become, likewise, an imitator of the best masters; while the discovery of new styles depended upon a more or less skilful combination of the old. Thus the sole career that remained open for the display of human genius was that of imitation; as it appeared impossible to design figures more masterly than those of Bonarruoti or Da Vinci, to express them with more grace than Raffaello, with more animated colours than those of Titian, with more lively motions than those of Tintoretto, or to give them a richer drapery and ornaments than Paul Veronese; to present them to the eye at every degree of distance, and in perspective, with more art, more fulness, and more enchanting power than fell to the genius of Coreggio. Accordingly the path of imitation was at that time pursued by every school, though with very little method. -

MONTEPULCIANO's PALAZZO COMUNALE, 1440 – C.1465: RETHINKING CASTELLATED CIVIC PALACES in FLORENTINE ARCHITECTURAL and POLITI

MONTEPULCIANO’S PALAZZO COMUNALE, 1440 – c.1465: RETHINKING CASTELLATED CIVIC PALACES IN FLORENTINE ARCHITECTURAL AND POLITICAL CONTEXTS Two Volumes Volume I Koching Chao Ph.D. University of York History of Art September 2019 ABSTRACT This thesis argues for the significance of castellated civic palaces in shaping and consolidating Florence’s territorial hegemony during the fifteenth century. Although fortress-like civic palaces were a predominant architectural type in Tuscan communes from the twelfth century onwards, it is an understudied field. In the literature of Italian Renaissance civic and military architecture, the castellated motifs of civic palaces have either been marginalised as an outdated and anti-classical form opposing Quattrocento all’antica taste, or have been oversimplified as a redundant object lacking defensive functionality. By analysing Michelozzo’s Palazzo Comunale in Montepulciano, a fifteenth-century castellated palace resembling Florence’s thirteenth-century Palazzo dei Priori, this thesis seeks to address the ways in which castellated forms substantially legitimised Florence’s political, military and cultural supremacy. Chapter One examines textual and pictorial representations of Florence’s castellation civic palaces and fortifications in order to capture Florentine perceptions of castellation. This investigation offers a conceptual framework, interpreting the profile of castellated civic palaces as an effective architectural affirmation of the contemporary idea of a powerful city-republic rather than being a symbol of despotism as it has been previously understood. Chapters Two and Three examine Montepulciano’s renovation project for the Palazzo Comunale within local and central administrative, socio-political, and military contexts during the first half of the fifteenth century, highlighting the Florentine features of Montepulciano’s town hall despite the town’s peripheral location within the Florentine dominion.