Supreme Court of the United States ------♦

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Sciences Alumni

Health Sciences Alumni Updated: 11/15/17 Allison Stickney 2018 High school science teaching Teach for America, Dallas-Fort Worth Sophia Sugar 2018 Research Assistant Nationwide Children’s Hosp., Columbus, OH Wanying Zhang 2017 Accelerated BSN, Nursing MGH Institute for Health Professions Kelly Ashnault 2017 Pharmacy Technician CVS Health Ian Grape 2017 Middle School Science Teacher Teach Kentucky Madeline Hobbs 2017 Medical Assistant Frederick Foot & Ankle, Urbana, MD Ryan Kennelly 2017 Physical Therapy Aide Professional Physical Therapy, Ridgewood, NJ Leah Pinckney 2017 Research Assistant UConn Health Keenan Siciliano 2017 Associate Lab Manager Medrobotics Corporation, Raynham, MA Ari Snaevarsson 2017 Nutrition Coach True Fitness & Nutrition, McLean VA Ellis Bloom 2017 Pre-medical fellowship Cumberland Valley Retina Consultants Elizabeth Broske 2017 AmeriCorps St. Bernard Project, New Orleans, LA Ben Crookshank 2017 Medical School Penn State College of Medicine Veronica Bridges 2017 Athletic Training UT Chattanooga, Texas A&M, Seton Hall Samantha Day 2017 Medical School University of Maryland School of Medicine Alexandra Fraley 2017 Epidemiology Research Assistant Department of Health and Human Services Genie Lavanant 2017 Athletic Training Seton Hall University Taylor Tims 2017 Nursing Drexel University, Johns Hopkins University Chase Stopyra 2017 Physical Therapy Rutgers School of Health Professions Madison Tulp 2017 Special education Teach for America Joe Vegso 2017 Nursing UPenn, Villanova University Nicholas DellaVecchia 2017 Physical -

CLASS of 2012 the One-Year-Out Report ELIZABETHTOWN COLLEGE

Elizabethtown College Class of 2012 CLASS OF 2012 The One-Year-Out Report ELIZABETHTOWN COLLEGE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Page 1 Elizabethtown College Class of 2012 Methodology This report includes information on the 376 undergraduate students from the traditional residential program who earned a degree at one of the 2012 conferrals: January, May, and August. Information for this survey was collected from multiple sources. Students provided preliminary information on a survey distributed at commencement rehearsal. They were additionally surveyed electronically approximately one year post-graduation. Additional information was provided by academic departments, the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), and LinkedIn. Through this process, responses were collected from 87% of the 2012 graduates. Outlook for 2012 Graduates According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE), the job outlook for 2012 college graduates was cautiously optimistic. Employers anticipated hiring 9-10% more college graduates from the class of 2012 than from the prior class of graduates. Still, the 2012 job market was highly competitive, with roughly 33 applications for every one job opening (CNNMoney ). A survey by Millennial Branding & Experience Inc. (2012, May 14) indicates that employers seek to hire individuals who have good communication skills, a positive attitude, the ability to adapt to changes, skills for effective teamwork, and who are goal oriented. Nationally, the average salary offer to 2012 college grads was expected to be $51,000 (NACE Fall 2011 Salary Survey). Compared with their peers without a college degree, college graduates can expect to accrue roughly one million dollars more in lifetime earnings. As this report shows, the 2012 graduates of Elizabethtown College fared well in the competitive marketplace they faced following graduation. -

Sept. 30 Issue Final

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Tuesday September 30, 2003 Volume 50 Number 6 www.upenn.edu/almanac Two Endowed Chairs in Political Science Dr. Ian S. Lustick, professor of political director of the Solomon Asch Center for Study ternational Organization, and Journal of Inter- science, has been appointed to the Bess Hey- of Ethnopolitical Conflict. national Law and Politics. The author of five man Professorship. After earning his B.A. at A specialist in areas of comparative politics, books and monographs, he received the Amer- Brandeis University, Dr. Lustick completed international politics, organization theory, and ican Political Science Associationʼs J. David both his M.A. and Ph.D. at the University of Middle Eastern politics, Dr. Lustick is respon- Greenstone Award for the Best Book in Politics California, Berkeley. sible for developing the computational model- and History in 1995 for his Unsettled States, Dr. Lustick came to ing platform known as PS-I. This software pro- Disputed Lands: Britain and Ireland, France Penn in 1991 following gram, which he created in collaboration with and Algeria, Israel and the West Bank-Gaza. In 15 years on the Dart- Dr. Vladimir Dergachev, GEngʼ99, Grʼ00, al- addition to serving as a member of the Council mouth faculty. From lows social scientists to simulate political phe- on Foreign Relations, Dr. Lustick is the former 1997 to 2000, he served nomena in an effort to apply agent-based model- president of the Politics and History Section of as chair of the depart- ing to public policy problems. His current work the American Political Science Association and ment of political sci- includes research on rights of return in Zionism of the Association for Israel Studies. -

SJU Launches Capital Campaign: with Faith and Strength to Dare

SJUMagazine_Cover:Final 7/28/09 12:38 PM Page 1 Saint Joseph’s University, Winter 2008 SJU Launches Capital Campaign: Lead Gift from Hagan Family Students Get a Share With Faith and Strength to Dare to Transform Fieldhouse of Wall Street — From Campus IFC Presidents Letter:Spring 2007 7/28/09 12:39 PM Page 1 FROM THE PRESIDENT As I walk around campus and interact with the wonderful individuals and groups that make up the Saint Joseph’s community, I am reminded of the wealth of programs — academic, administrative, social and spiritual — that continue to lead us on the path to preeminence outlined in Plan 2010. As we move forward with this plan, few initiatives will be as crucial to its success as With Faith and Strength to Dare: The Campaign for Saint Joseph’s University. Earlier this fall, the campaign began in earnest with a weekend of events, including a spectacular gala to celebrate the progress made during the campaign’s silent phase and to anticipate the success going forward. A recap of this historic evening and more details of the campaign are conveyed in this magazine’s cover story. The campaign’s escalating momentum reinforces our goal of being recognized as the preeminent Catholic, comprehensive university in the Northeast. As the University’s first comprehensive campaign, With Faith and Strength to Dare is about fulfilling that vision as well as giving it meaning. Preeminence is about much more than being “bigger and better.” It is about offering the best possible living and learning experience, so we can provide to the world individuals who have critical thinking skills, intellectual curiosity and the moral discernment rooted in Christian values to create a caring and just society — to be men and women with and for others. -

Executive Mba for Physicians

EXECUTIVE MBA FOR PHYSICIANS AN ACCELERATED 16-MONTH PROGRAM FOR PHYSICIAN LEADERS heller.brandeis.edu/physiciansemba The Heller Executive MBA for Physicians Improving patient care experiences, clinical “Compared to a traditional EMBA, outcomes, and decision-making efficiency this one taught the subjects with a The Heller School’s Executive MBA (EMBA) for Physicians is healthcare focus. My interests aligned focused on improving clinical outcomes, financial performance, much better with my classmates; and patient experiences in healthcare organizations. It is we all speak the same language and designed for practicing physicians who are – or seek to be – in executive positions of management or leadership. The understand each other.” accelerated 16-month program trains physician leaders in the new science of medicine and management by integrating Amir Taghinia, MD, MBA students’ medical expertise with new knowledge in critical Staff Surgeon areas ranging from health policy and economics to operations, Boston Children’s Hospital high performance leadership, and healthcare innovation. “The balance of on-site and remote Why do physicians need an MBA? classes works incredibly well. Today’s highly complex healthcare landscape is rife with The technology and conduct of the medical reforms and regulations that challenge established remote sessions keep you in close management assumptions and behaviors. At the same time, healthcare demands high quality, patient-centered care and contact with classmates, which is an dramatically decreased costs. Leaders must have advanced essential component of the program.” expertise in both clinical care and management to ensure optimal medical outcomes and robust financial performance. Evan Lipsitz, MD, MBA Chief, Division of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Neither medical nor business schools teach this essential Montefiore Medical Center and the Albert Einstein combination of medicine and management required to lead College of Medicine the 21st-century healthcare institution or practice. -

The One Hundred and Thirty-Fifth Commencement 1998 La Salle University

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons La Salle Commencement Programs University Publications 1998 The One Hundred and Thirty-Fifth Commencement 1998 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/commencement_programs Recommended Citation La Salle University, "The One undrH ed and Thirty-Fifth ommeC ncement 1998" (1998). La Salle Commencement Programs. 67. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/commencement_programs/67 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in La Salle Commencement Programs by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ONE HUNDRED AND THIRTY-FIFTH COMMENCEMENT Sunday, Ma) 17, L998 eleven o'clock in the morning McCarthy m \im \i NOTES ON ACADEMIC DRESS* The history of academic dress begins in the early days of the oldest universities. A statute of 1 321 required all "Doctors, Licentiates, and Bachelors" of the University of Coimbra to wear gowns. In England during the second half of the 14th century, the statutes of certain colleges forbade "excess in apparel" and prescribed the wearing of a long gown. It is still a question whether academic dress finds its sources chiefly in ecclesiastical or in civilian dress. Gowns may have been considered necessary for warmth in the unheated buildings used by medieval scholars. Hoods may have served to cover the tonsured head until superseded for that purpose by the skull cap. The cap was later displaced by a headdress similar to ones now recognized as "academic." European institutions continue to show great diversity in their specifications of academic dress. -

Pezzimenti CV

Samantha Pezzimenti June 12, 2017 Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania Education • Bryn Mawr College Bryn Mawr, PA Ph.D Mathematics (in progress) Expected May 2018 M.A. Mathematics May 2015 • Ramapo College of New Jesery Mahwah, NJ B.S. Mathematics May 2012 { Graduated Suma Cum Laude with honors and distinction, with a 3.99 GPA { Studied abroad at Kingston University in London, UK, July 2009 { Honor Societies: Alpha Lambda Delta, Pi Mu Epsilon, Golden Key Honor Society Research Experience • Ph.D. Candidate Bryn Mawr College Immersed Lagrangian Fillings of Legendrian Knots November 2015 - Present Advisor: Lisa Traynor • Master's Thesis Bryn Mawr College Minimal Genus Lagrangian Caps of Legendrian Knots May 2014 - May 2015 Advisor: Lisa Traynor • Undergraduate Research Ramapo College of New Jersey Minimal Degree Parameterizations of the Trefoil and Figure Eight Knots May 2011 - August 2012 Advisor: Donovan McFeron Teaching Experience • Adjunct Professor Ocean County College Calculus II Summer 2016 • Teaching Assistant Bryn Mawr College Undergraduate Courses 2012-Present { Taught a section of Calculus II (Spring 2017). { Courses TA-ed: Multivariable Calculus, Linear Algebra, Knot Theory, Probability, Analysis, Abstract Algebra, Combinatorics, Topology ∗ Grade homework assignments and exams. ∗ Lead multiple problem sessions each week. ∗ Substitute teach and give occasional lectures. • Mathematics Tutor Ramapo College Undergraduate Courses 2009-2012 { Courses: Elementary Algebra, Transitional Mathematics, Math for the Modern World, Calculus { Tutored students in mathematics both one-on-one and in small groups. { Ran review sessions along with Professor. • Reading and Writing Workshop Instructor Ramapo College High School English Fall 2011 { Weekly after-school program at Ramsey High School, in collaboration with Ramapo College, for students who seek extra help in reading and writing. -

(MUS) Fall 2021 Department of Music Chairperson Christina Dahl Staller

MUSIC (MUS) Fall 2021 Department of Music Chairperson Christina Dahl Staller Center 3304 (631) 632-7330 Graduate Program Director Erika Honisch Staller Center 3346 (631) 632-4433 Degrees Awarded M.A. in Music History and Theory; M.A. in Ethnomusicology; M.A. in Composition; M.M. in Music Performance; Ph.D. in History and Theory; Ph.D in Ethnomusicology; Ph.D. in Composition; D.M.A. in Music Performance. Website https://www.stonybrook.edu/commcms/music/ Application Applications to our programs can be found on our website here: https://www.stonybrook.edu/commcms/music/academics/_graduate/index.php Description of the Department of Music The Department of Music offers programs that normally lead to the Doctor of Philosophy degree in Music History and Theory, in Ethnomusicology, and in Composition. The Department also offers programs that normally lead to the Doctor of Musical Arts degree in Music Performance. Masters Degrees in Music History and Theory, in Ethnomusicology, in Composition, and in Music Performance are also available. Stony Brook’s programs have grown out of an unusual partnership between the academy and the conservatory. The Music Department has a distinguished and well-balanced faculty in the areas of music history, theory, ethnomusicology, composition, and performance. The degree programs are designed to favor interaction among musical disciplines that have traditionally been kept separate. For example, the performance programs at Stony Brook all have an academic component. Graduate courses typically have a healthy mix of students from all areas. A number of courses are team taught by two or more faculty members, examining topics from several disciplinary viewpoints. -

La Salle College Bulletin: Catalog Issue 1967-1968 La Salle University

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons La Salle Course Catalogs University Publications 1967 La Salle College Bulletin: Catalog Issue 1967-1968 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/course_catalogs Recommended Citation La Salle University, "La Salle College Bulletin: Catalog Issue 1967-1968" (1967). La Salle Course Catalogs. 81. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/course_catalogs/81 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in La Salle Course Catalogs by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CO a More than buildings, more than books, more than lectures and examinations, education is a matter of people. It is the people who make up La Salle- the students and tht teachers -who give the college its character. PHILADELPHIA. PENNENNS YLVAN I. La Salle College Bulletin CATALOGUE ISSUE 1967-68 A LIBERAL ARTS COLLEGE FOR MEN CONDUCTED BY BROTHERS OF THE CHRISTIAN SCHOOLS PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA ACCREDITATION AND MEMBERSHIP La Salle College was chartered in 1863 by the Legislature of the Common- wealth of Pennsylvania and is empowered by that authority to grant aca- demic degrees. It is accredited with the Middle States Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools, the Pennsylvania State Department of Public In- struction, the Regents of the University of the State of New -

History of Elizabethtown College

Elizabethtown College Catalog 2000-2001 Contents Introduction ..................... 2 Interdisciplinary Educational Philosophy and Programs....................... 166 Institutional Values ............................... 2 Biology/Allied Health .......................... 166 Academic Goals ....................................... 4 Premedical Primary Care Service-Learning Statement .................... 6 Program ............................................ 167 History of Elizabethtown College ........... 6 Premedical and Other Health Elizabethtown College Professions Programs .................... 169 At-a-Glance .............................................. 8 Primary Care Pre-Admissions Admission to the College ......................... 13 Program ............................................ 170 Financial Aid Information ...................... 15 Forestry and Environmental Management .................................... 171 Academic Program ..........26 Political Philosophy Major and Degrees Offered ......................................... 26 Legal Studies ................................... 172 The Core Program .................................... 26 Pre-Law Program ................................. 173 Academic Majors ....................................... 32 Social Studies Certification ............... 173 Academic Minors....................................... 33 General Science Certification and Program Variations and Options .......... 33 Minor .......................................... 174/175 Hershey Foods Honors Program .......... -

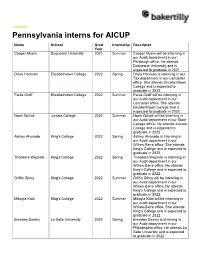

Pennsylvania Interns for AICUP

Pennsylvania interns for AICUP Name School Grad Internship Descriptor Year Cooper Myers Duquesne University 2021 Summer Cooper Myers will be interning in our Audit department in our Pittsburgh office. He attends Duquesne University and is expected to graduate in 2021. Olivia Harrison Elizabethtown College 2022 Spring Olivia Harrison is interning in our Tax department in our Lancaster office. She attends Elizabethtown College and is expected to graduate in 2022. Paula Groff Elizabethtown College 2022 Summer Paula Groff will be interning in our Audit department in our Lancaster office. She attends Elizabethtown College and is expected to graduate in 2022. Noah Zolnak Juniata College 2022 Summer Noah Zolnak will be interning in our Audit department in our State College office. He attends Juniata College and is expected to graduate in 2022. Ashley Alvarado King's College 2022 Spring Ashley Alvarado is interning in our Audit department in our Wilkes-Barre office. She attends King's College and is expected to graduate in 2022. Theodore Wozniak King's College 2022 Spring Theodore Wozniak is interning in our Audit department in our Wilkes-Barre office. He attends King's College and is expected to graduate in 2022. Griffin Gilroy King's College 2022 Summer Griffin Gilroy will be interning in our Audit department in our Wilkes-Barre office. He attends King's College and is expected to graduate in 2022. Mikayla Kidd King's College 2022 Summer Mikayla Kidd will be interning in our Audit department in our Wilkes-Barre office. She attends King's College and is expected to graduate in 2022. -

History of Misericordia University 1924 – 2016

FACULTY RESEARCH RESEARCH FACULTY & SCHOLARLY WORK • WORK SCHOLARLY 2015–2016 MISERICORDIA UNIVERSITY Faculty Research & Scholarly Work 2015 – 2016 Mercy Hall, the main administration building, 1 was built in 1924. 2 MISERICORDIA UNIVERSITY Faculty Research & Scholarly Work 2015-16 Occupational therapy research Biology major’s research shows Assistive Technology Research project studies effectiveness best method for restoring ocean Institute collaborates on of a transitional and vocational shorelines and repopulating international Global Public training program for special them with native species as Inclusive Infrastructure project to needs students. – Page 4 part of Summer Research open the Internet to users of all Fellowship Program. – Page 8 abilities and ages. – Page 12 A periodic publication of the Office of Public Relations & Publications at Misericordia University, 2015-16 301 Lake St., Dallas, PA 18612 | misericordia.edu | 1-866-262-6363 3 College of Health Sciences and Education Growing opportunities to expand the mind Misericordia University OT research project studies effectiveness of a transitional vocational training program for special needs students at Lands at Hillside Farms JACKSON TWP., Pa. – The crisp fall morning does There are so many other things to do little to deter Brandon Dewey, 17, of Dallas from here. We learn people skills when we are preparing a portion of the Dream Green Farm down there (at the Wilkes-Barre Farmers Program’s farmland at the Lands at Hillside Farms Market). Math is a good idea, because for planting its most popular crop – garlic. Dressed you have to count the cash and give in a short-sleeved pocket T-shirt, the Luzerne people their change.’’ Intermediate Unit 18 (LIU) student carefully follows The Dream Green Farm Program a string-lined path to punch small holes in the earth was born in 2009 with the assistance of with a long garden tool handle.