Cole and Cole (2015)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cienegas Vanishing Climax Communities of the American

Hendrickson and Minckley Cienegas of the American Southwest 131 Abstract Cienegas The term cienega is here applied to mid-elevation (1,000-2,000 m) wetlands characterized by permanently saturated, highly organic, reducing soils. A depauperate Vanishing Climax flora dominated by low sedges highly adapted to such soils characterizes these habitats. Progression to cienega is Communities of the dependent on a complex association of factors most likely found in headwater areas. Once achieved, the community American Southwest appears stable and persistent since paleoecological data indicate long periods of cienega conditions, with infre- quent cycles of incision. We hypothesize the cienega to be an aquatic climax community. Cienegas and other marsh- land habitats have decreased greatly in Arizona in the Dean A. Hendrickson past century. Cultural impacts have been diverse and not Department of Zoology, well documented. While factors such as grazing and Arizona State University streambed modifications contributed to their destruction, the role of climate must also be considered. Cienega con- and ditions could be restored at historic sites by provision of ' constant water supply and amelioration of catastrophic W. L. Minckley flooding events. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Dexter Fish Hatchery Introduction and Department of Zoology Written accounts and photographs of early explorers Arizona State University and settlers (e.g., Hastings and Turner, 1965) indicate that most pre-1890 aquatic habitats in southeastern Arizona were different from what they are today. Sandy, barren streambeds (Interior Strands of Minckley and Brown, 1982) now lie entrenched between vertical walls many meters below dry valley surfaces. These same streams prior to 1880 coursed unincised across alluvial fills in shallow, braided channels, often through lush marshes. -

Notices of Public Information 3489

Arizona Administrative Register Notices of Public Information NOTICES OF PUBLIC INFORMATION Notices of Public Information contain corrections that agencies wish to make to their notices of rulemaking; miscella- neous rulemaking information that does not fit into any other category of notice; and other types of information required by statute to be published in the Register. Because of the variety of material that is contained in a Notice of Public Information, the Office of the Secretary of State has not established a specific format for these notices. NOTICE OF PUBLIC INFORMATION DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY 1. A.R.S. Title and its heading: 49, The Environment A.R.S. Chapter and its heading: 2, Water Quality Control A.R.S. Article and its heading: 2.1, Total Maximum Daily Loads A.R.S. Sections: A.R.S. § 49-232, Lists of Impaired Waters; Data Requirements; Rules 2. The public information relating to the listed statute: A.R.S. § 49-232(A) requires the Department to at least once every five years, prepare a list of impaired waters for the pur- pose of complying with section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act (33 U.S.C. 1313(d)). The Department shall provide public notice and allow for comment on a draft list of impaired waters prior to its submission to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The Department shall prepare written responses to comments received on the draft list. The Department shall publish the list of impaired waters that it plans to submit initially to the regional administrator and a summary of the responses to comments on the draft list in the Arizona Administrative Register at least forty-five days before submission of the list to the regional administrator. -

Eyec Sail Dzan

Desert Plants, Volume 6, Number 3 (1984) Item Type Article Authors Hendrickson, Dean A.; Minckley, W. L. Publisher University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Journal Desert Plants Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 27/09/2021 19:02:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/552226 Desert Volume 6. Number 3. 1984. (Issued early 1985) Published by The University of Arizona at the Plants Boyce Thompson Southwestern Arboretum eyec sail Dzan Ciénegas Vanishing Climax Communities of the American Southwest Dean A. Hendrickson and W. L. Minckley O'Donnell Ciénega in Arizona's upper San Pedro basin, now in the Canelo Hills Ciénega Preserve of the Nature Conservancy. Ciénegas of the American Southwest have all but vanished due to environmental changes brought about by man. Being well- watered sites surrounded by dry lands variously classified as "desert," "arid," or "semi- arid," they were of extreme importance to pre- historic and modern Homo sapiens, animals and plants of the Desert Southwest. Photograph by Fritz jandrey. 130 Desert Plants 6(3) 1984 (issued early 1985) Desert Plants Volume 6. Number 3. (Issued early 1985) Published by The University of Arizona A quarterly journal devoted to broadening knowledge of plants indigenous or adaptable to arid and sub -arid regions, P.O. Box AB, Superior, Arizona 85273 to studying the growth thereof and to encouraging an appre- ciation of these as valued components of the landscape. The Boyce Thompson Southwestern Arboretum at Superior, Arizona, is sponsored by The Arizona State Parks Board, The Boyce Thompson Southwestern Arboretum, Inc., and The University of Arizona Frank S. -

Geothermal Resource Potential for a Portion of the San Pedro River Valley, Arizona

GEOTHERMAL RESOURCE POTENTIAL FOR A PORTION OF THE SAN PEDRO RIVER VALLEY, ARIZONA by W. Richard Rahman, Sr. Arizona Geological Survey Open-File Report 81-6 Apri11981 Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress, Suite #100, Tucson, Arizona 85701 Funded by the u.s. Department ofEnergy Contract Number DE-FC07-79ID12009 This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with Arizona Geological Survey standards RECONNAISSANCE STUDY GEOTHERMAL RESOURCE POTENTIAL OF A PORTION OF THE SAN PEDRO RIVER VALLEY INTRODUCTION A preliminary investigation of the geothermal resource potential of the San Pedro River valley was undertaken the latter part of 1980. The area of investigation is situated in Pinal, Pima and Cochise counties, Arizona. It extends from the town of Mammoth, Pinal County, south-southeast along the river valley to just north of the Johnny Lyon 2 2 Hills, an area comprising 2331 km (900 mi ). With the exception of mining and smelting activities in the Mammoth-San Manuel area, the primary business in the valley is agriculture, cattle ranching and forage crops. The majority of the irrigation, livestock, and domestic wells are along the bed of the San Pedro River, an ephemeral stream that flows northward from its headwaters in Mexico. The wells generally vary in depth from 24 m (80 ft) to 36 m (120 ft) and essentially produce from the subsurface river flow. In the Mammoth-San Manuel area there are some warm artesian wells that vary in depth from approximately 244 m (800 ft) to 457 m (1500 ft). The warmest temperature 0 o measured in these wells was 40 C (104 F). -

The Arizona Department of Water Resources Cochise, Graham and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona—Dec. 2001- Jan. 2002 by R.L. Barnes

D.W.R HYDROLOGIC MAP SERIES REPORT NO. 34 PREPARED IN COOPERATION WITH THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY THE ARIZONA DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES DEPTH TO WATER AND ALTITUDE OF THE WATER LEVEL SHEET 1 OF 2 114 113 112 111 110 109 Based on 1968 data, a small elliptical cone of depression was first described by Roeske and Werrell, (1973, p.16). The 37 37 With the exception of the Pantano (?) Formation, all of the previously mentioned basin-fill units are also present in Allen Flat, depression was enclosed within the 4,150 foot contour. It encompassed about 5 square miles and was centered in section 33, however, the units are not as thick (Putman and others, 1988, p. 65). Depth to bedrock in the Allen Flat sub-basin has been Township 21 South, Range 20 East. The major axis of the elliptical cone was northeast-southwest in orientation. Data col- estimated to be from 1,600 to 3,200 feet (Oppenheimer and Sumner, 1980, map). lected by the U. S. Geological Survey in the winter of 1977-78 supports Konieczki’s (1980, sheet 1) reference to the small depression centered within the 4,150 foot contour near Sierra Vista-Fort Huachuca. Putman and others (1988, p.98), using GROUNDWATER OCCURRENCE data collected in the winter of 1985-86, stated that the cone of depression within the 4,150 foot contour still extended in a northeast-southwest direction, and had increased areally to the east and southeast of Sierra Vista, to about 7.5 square miles. A T R 21 E The predominant aquifers in the Upper San Pedro Basin are the basin-fill deposits and the floodplain alluvium (Roeske and maximum decline of 9.2 feet was observed between 1985 and 1990 at well (D-21-21) 31CAC, while the minimum observed 36 36 decline was 2.2 feet at well (D-21-20) 35CBC for this period. -

Management Opportunities in Support of Riparian Values

ASSESSMENT OF WATER CONDITIONS ANI) MANAGEMENT OPPORTUNITIES IN SUPPORT OF RIPARIAN VALUES: BLM San Pedro River Properties, Arizona Project Completion Report by William Jackson, I Tony Martinez,2 Paul Cuplin, 3 W.L. Minkley,4 Bo Shelby,5 Paul Summers,6 Dan McGlothlin, 7 Bruce Van Haveren, 8 BLWYA/PT-88/ffi4+7200 May 1987 U.S. Departrnent of Interior Bureau of Land Management Service Center P.O. Box 25M7 Denver, CO 80225-ffi47 1. Hydrologisg Project Leader, Bureau of land Management Service Center 2. Anorney and Water Rights Specialist, Bureau of Land Management Colorado State Office 3. Fisheries Biologist and Riparian Specialist, Bureau of [.and Management Service Center 4. Professor of Zoology, Arizona State University 5. Associate kofqssor of Resource Recreation, Oregon State University 5. Hydrogeologist, Bureau of Land Manageme,nt Service Center 7. Hydrologist, Bureau of Land Management Arizona State Office 8. Hydrologist, Bureau of Land Management Service Center United States Department of the Interior BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT ARIZONA STATE OFFICE P.O. Box 16563 7th Sreet 3707 N. IN REPLY REFER TO: Phoenix. Arizona 85011 This document is the final report of a project prepared by the Bureau of Land l,lanagement's (gtt,l) Denver Servlce Center for the Safford Dlstrict 0ffice in Ariz6na. The project, inltiated by the Arizona State Office, was deslgned and implemented by the San Pedro River Study Team, a group of multldisclplinary professional s specia'l i zi ng i n hydrol ogy, geomorphol ogy, hydrogeol ogy' iisheries biology, riparian ecology, water rlghts and natural resource rec reation. This report: (a) presents information on the condition of water resources in the San Pedro River Management Area, (b) iustlfies the quantification of instream dependent uses identified in the area and (c) examines and recommends strategies for protecting or enhancing the ldentified water-related values. -

Fishes and Aquatic Habitats of the Upper San Pedro River System, Arizona and Sonora

FISHES AND AQUATIC HABITATS OF THE UPPER SAN PEDRO RIVER SYSTEM, ARIZONA AND SONORA by W. L. Minckley, Ph.D. Professor of Zoology, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 85287 Final Report for Purchase Order YA-558-CT7-001 U. S. Bureau of Land Management, Denver Federal Center, Building 50, P.O. Box 25047, Denver, Colorado 80225 March 1987 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...... 1 Objectives 1 ...................................... DESCRI ON OF THE STUDY AREA 3 ...................................... HISTORIC AQUATIC CONDITIONS 6 .......................................... Man in the Upper San Pedro Valle:- 7 Aquatic Habitats of th,-, Past 10 ......................................... Permanence 13 ..................................... FISHES OF THE SAN PEDRO BASIN 14 ......................................... History of Study 14 Patterns of Ichthyofaunal Chanqe 16 Past Habitats and Fish Communities 19 Habitat Size ..... 20 Measures of Stability 22 Heterogeneity ..... 22 Species' Ecologies Relevant to Available Habitats ..... 23 Category I ..... 23 Category II ..... 27 Category III ..... 29 Category IV ..... 33 FACTORS AFFECTING LIFE HISTORIES OF NATIVE FISHES ... 37 ACTUAL AND POTENTIAL IMPACTS OF UPSTREAM M -:1.3 OPERATIONS 41 ENHANCEMENT OF SAN PEDRO RIVER FISH HABITATS ... 46 Semi-natural Habitats 47 Rehabilitation of the Natural Channel ...51 REINTRODUCTIONS AND MANAGEMENT OF NATIVE FISHES ...53 Philosophies,, 'roblems, and Realism= 53 Recommendations for Reintroduction and Management ...57 BIBLIOGRAPHY 62 INTRODUCTION Acquisition of much of the upper San Pedro River in the United States by the Bureau of Land Management (USBLM; Rosenkrance 1986) and its proposed designation as a "San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area" (hereafter Conservation Area; USBLM 1986) presents a possibility for protection and management of a Southwestern stream and its plant and animal resources. Part of those resources are fishes, which due to their absolute dependence on surface water are sorely endangered. -

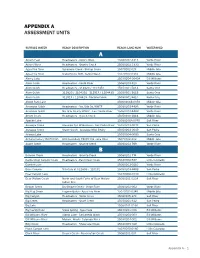

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED A Ackers East Headwaters - Ackers West 15060202-3313 Verde River Ackers West Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-3333 Verde River Agua Fria River Sycamore Creek - Bishop Creek 15070102-023 Middle Gila Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo Lake 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alder Creek Headwaters - Verde River 15060203-910 Verde River Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820 / 1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - Aravaipa Wild. Bndry 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arizona Canal (15070102) HUC boundary 15070102 - Gila River 15070102-202 Middle Gila Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River B Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bass Canyon Tributary at 322606 / 110131 15050203-899B San Pedro -

Geothermal Resource Potential for a Portion of the San Pedro River Valley, Arizona

GEOTHERMAL RESOURCE POTENTIAL FOR A PORTION OF THE SAN PEDRO RIVER VALLEY, ARIZONA by W. Richard Rahman, Sr. Arizona Geological Survey Open-File Report 81-6 April 1981 Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress, Suite #100, Tucson, Arizona 85701 Funded by the U.S. Department ofEnergy Contract Number DE-FC07-79ID12009 This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with Arizona Geological Survey standards RECONNAISSANCE STUDY GEOTHERMAL RESOURCE POTENTIAL OF A PORTION OF THE SAN PEDRO RIVER VALLEY INTRODUCTION A preliminary investigation of the geothermal resource potential of the San Pedro River valley was undertaken the latter part of 1980. The area of investigation is situated in Pinal, Pima and Cochise counties, Arizona. It extends from the town of Mammoth, Pinal County, south-southeast along the river valley to just north of the Johnny Lyon 2 2 Hills, an area comprising 2331 km (900 mi ). With the exception of mining and smelting activities in the Mammoth-San Manuel area, the primary business in the valley is agriculture, cattle ranching and forage crops. The majority of the irrigation, livestock, and domestic wells are along the bed of the San Pedro River, an ephemeral stream that flows northward from its headwaters in Mexico. The wells generally vary in depth from 24 m (80 ft) to 36 m (120 ft) and essentially produce from the subsurface river flow. In the Mammoth-San Manuel area there are some warm artesian wells that vary in depth from approximately 244 m (800 ft) to 457 m (1500 ft). The warmest temperature 0 o measured in these wells was 40 C (104 F). -

The Development of Piping Erosion

The development of piping erosion Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic); maps Authors Jones, Neil Owen Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 12:01:34 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565170 THE DEVELOPMENT OF PIPING EROSION Neil Owen Jones, Ph. D. The University of Arizona, 1968 Director: Lawrence K. Lustlg Piping erosion is widespread in the semiarid valleys of the southwestern United States. The extensive pipe sys tems near Benson in the San Pedro Valley, Arizona, were studied to determine the prerequisite conditions for piping, factors affecting pipe evolution and the effect of piping on subsequent development of the drainage net. It is believed that extensive piping was initiated after arroyo-cuttlng began in the San Pedro Valley about 1890. Since that time slightly less than 10 percent of the Aravalpa Surface has been affected by piping, but the af fected area includes some 40 percent of the cultivated land, most of which is adjacent to the river. Field studies in cluded determination of the geomorphic and hydrologic set ting of the major pipe systems and detailed mapping of rep resentative pipe systems to determine the influence of local geologic structures on piping. Changes in a representative pipe system during the study period were measured. Se quences of aerial photographs for the period 1935-66 indicate the long-term rate of development of pipe systems and their relation to the drainage net. -

Section VII Potential Linkage Zones SECTION VII POTENTIAL LINKAGE ZONES

2006 ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT 41 Section VII Potential Linkage Zones SECTION VII POTENTIAL LINKAGE ZONES Linkage 1 Linkage 2 Beaver Dam Slope – Virgin Slope Beaver Dam – Virgin Mountains Mohave Desert Ecoregion Mohave Desert Ecoregion County: Mohave (Linkage 1: Identified Species continued) County: Mohave Kit Fox Vulpes macrotis ADOT Engineering District: Flagstaff and Kingman Mohave Desert Tortoise Gopherus agassizii ADOT Engineering District: Flagstaff ADOT Maintenance: Fredonia and Kingman Mountain Lion Felis concolor ADOT Maintenance: Fredonia ADOT Natural Resources Management Section: Flagstaff Mule Deer Odocoileus hemionus ADOT Natural Resources Management Section: Flagstaff Speckled Dace Rhinichthys osculus Spotted Bat Euderma maculatum AGFD: Region II AGFD: Region II Virgin Chub Gila seminuda Virgin Spinedace Lepidomeda mollispinis mollispinis BLM: Arizona Strip District Woundfin Plagopterus argentissimus BLM: Arizona Strip District Congressional District: 2 Threats: Congressional District: 2 Highway (I 15) Council of Government: Western Arizona Council of Governments Urbanization Council of Government: Western Arizona Council of Governments FHWA Engineering: A2 and A4 Hydrology: FHWA Engineering: A2 Big Bend Wash Legislative District: 3 Coon Creek Legislative District: 3 Virgin River Biotic Communities (Vegetation Types): Biotic Communities (Vegetation Types): Mohave Desertscrub 100% Mohave Desertscrub 100% Land Ownership: Land Ownership: Bureau of Land Management 59% Bureau of Land Management 93% Private 27% Private -

ARIZONA LOCAL PUBLIC AGENCY SYSTEM BRIDGE RECORD As of 4/12/2021 Sorted by Agency Excludes City of Phoenix

ARIZONA LOCAL PUBLIC AGENCY SYSTEM BRIDGE RECORD As of 4/12/2021 Sorted by Agency Excludes City of Phoenix Agency Str No Bridge Name Original Construction Project No Year Built Mat Type No of Spans Max Span Length Ft Structure Length Ft Skew Roadway Appr Width Ft Bridge Roadway Width Ft Allow Vert Clearance Ft Overlay In Bridge Rail Type Def SR Bridge Condition NHS On System Apache Co 07731 San Fran River CMPA 1988 3 19 3 6 21 0 24 38.8 0 2 000 98.5 Good Apache Co 08064 Little Colo River Br NON SYS 1934 1 1 1 27 30 0 18 14.2 0 6 600 58.9 Fair Apache Co 08066 Small Wash Bridge FAP 73 1929 1 4 1 28 32 45 24 28 0 400 79.5 Fair Apache Co 08071 Querino Canyon Br FAP 83-A 1931 3 9 5 77 269 0 18 20 0 600 S 19.3 Poor YES Apache Co 08480 Concho Creek Bridge 1900 1 1 1 30 34 0 15 17.5 0 2 400 80.1 Fair Apache Co 08775 RCB 1931 2 19 3 12 38 0 20 22.6 0 0 000 81.2 Good YES Apache Co 08776 SPPA's 1931 3 19 4 6 30 0 20 0 0 87.7 Fair YES Apache Co 08778 Ltl Colo Rvr SPPA's 1982 3 19 3 45 165 45 31 0 0 89.9 Good Apache Co 09048 Chambers Wash RCB S450 1 1966 2 19 5 10 53 0 27 0 0 99.9 Good YES Apache Co 09049 Navapache Wash RCB S450 1 1966 2 19 4 10 43 0 27 0 0 99.9 Good YES Apache Co 09052 Sepulveda Wash RCB S272 1 1958 2 19 2 12 25 0 26 0 0 99.5 Fair YES Apache Co 09621 Seep Draw SPPA 1980 3 19 1 32 32 0 24 0 0 98.0 Good YES Apache Co 09738 Mail Sta Draw SPPA 1982 3 19 1 24 24 0 20 0 0 99.3 Good YES Apache Co 09901 Bonito Wash Bridge 0 1985 4 2 2 17 35 0 24 24 0 2 600 66.3 Fair Apache Jct 07727 Weekes Wash Bridge F-028-1-513 1990 5 2 1 61 63 0 32 31.6