Eyec Sail Dzan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Rana Chiricahuensis)

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Rana chiricahuensis) Final Recovery Plan April 2007 CHIRICAHUA LEOPARD FROG (Rana chiricahuensis) RECOVERY PLAN Southwest Region U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Albuquerque, New Mexico DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and are sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, state agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director, or Director, as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. Literature citation of this document should read as follows: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Rana chiricahuensis) Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Southwest Region, Albuquerque, NM. 149 pp. + Appendices A-M. Additional copies may be obtained from: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Field Office Southwest Region 2321 West Royal Palm Road, Suite 103 500 Gold Avenue, S.W. -

![Tumacacori Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation [PW-05-03-D2-001]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1332/tumacacori-potential-wilderness-area-evaluation-pw-05-03-d2-001-81332.webp)

Tumacacori Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation [PW-05-03-D2-001]

Tumacacori Potential Wilderness Evaluation Report Tumacacori Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation [PW-05-03-D2-001] Area Overview Size and Location: The Tumacacori Potential Wilderness Area (PWA) encompasses 37,330 acres. This area is located in the Tumacacori and Atacosa Mountains, which are part of the Nogales Ranger District of the Coronado National Forest in southeastern Arizona (see Map 4 at the end of this document). The Tumacacori PWA is overlapped by 30,305 acres of the Tumacacori Inventoried Roadless Area, comprising 81 percent of the PWA. Vicinity, Surroundings and Access: The Tumacacori Potential Wilderness Area is approximately 50 miles southeast of Tucson, Arizona. The Tumacacori PWA is centrally located within the mountain range and encompasses an area from Sardina and Tumacacori Peaks at the northern end to Ruby Road at the southern end and from the El Paso Natural Gas Line on the eastern side to Arivaca Lake on its western side. The PWA is adjacent to the Pajarita Wilderness Area, Arivaca Lake and Peña Blanca Lake. Both Pena Blanca and Arivaca Lakes are managed by the Arizona Game and Fish Department. Interstate 19 (I-19) connects the Tucson metropolitan area to the City of Nogales and the incorporated community of Sahuarita. The unincorporated communities of Green Valley, Arivaca Junction-Amado, Tubac, Tumacacori-Carmen and Rio Rico, Arizona and Sonora, Mexico are within close proximity to the eastern side of the Tumacacori Mountains and the PWA. State Highway 289 provides access from I-19 across private and National Forest System lands into the Tumacacori Ecosystem Management Area to Peña Blanca Lake and Ruby Road (NFS Road 39). -

Arizona by Ric Windmiller 3

THE COCHISE QUARTERLY Volume 1 Number 2 June, 1971 CONTENTS Early Hunters and Gatherers in Southeastern Arizona by Ric Windmiller 3 From Rocks to Gadgets A History of Cochise County, Arizona by Carl Trischka 16 A Cochise Culture Human Skeleton From Southeastern Arizona by Kenneth R. McWilliams 24 Cover designed by Ray Levra, Cochise College A Publication of the Cochise County Historical and Archaeological Society P. O. Box 207 Pearce, Arizona 85625 2 EARLY HUNTERS AND GATHERERS IN SOUTHEASTERN ARIZONA* By Ric Windmiller Assistant Archaeologist, Arizona State Museum, University of Arizona During the summer, 1970, the Arizona State Museum, in co- operation with the State Highway Department and Cochise County, excavated an ancient pre-pottery archaeological site and remains of a mammoth near Double Adobe, Arizona.. Although highway salvage archaeology has been carried out in the state since 1955, last sum- mer's work on Whitewater Draw, near Double Adobe, represented the first time that either the site of early hunters and gatherers or re- mains of extinct mammoth had been recovered through the salvage program. In addition, excavation of the pre-pottery Cochise culture site on a new highway right-of-way has revealed vital evidence for the reconstruction of prehistoric life-ways in southeastern Arizona, an area that is little known archaeologically, yet which has produced evidence to indicate that it was early one of the most important areas for the development of and a settled way of life in the Southwest. \ Early Big Game Hunters Southeastern Arizona is also important as the area in which the first finds in North America of extinct faunal remains overlying cul- tural evidences of man were scientifically excavated. -

On the Pima County Multi-Species Conservation Plan, Arizona

United States Department of the Interior Fish and ,Vildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Office 2321 West Royal Palm Road, Suite 103 Phoenix, Arizona 85021-4951 Telephone: (602) 242-0210 Fax: (602) 242-2513 In reply refer to: AESO/SE 22410-2006-F-0459 April 13, 2016 Memorandum To: Regional Director, Fish and Wildlife Service, Albuquerque, New Mexico (ARD-ES) (Attn: Michelle Shaughnessy) Chief, Arizona Branch, Re.. gul 7/to . D'vision, Army Corps of Engineers, Phoenix, Arizona From: Acting Field Supervisor~ Subject: Biological and Conference Opinion on the Pima County Multi-Species Conservation Plan, Arizona This biological and conference opinion (BCO) responds to the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) requirement for intra-Service consultation on the proposed issuance of a section lO(a)(l)(B) incidental take permit (TE-84356A-O) to Pima County and Pima County Regional Flood Control District (both herein referenced as Pima County), pursuant to section 7 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (U.S.C. 1531-1544), as amended (ESA), authorizing the incidental take of 44 species (4 plants, 7 mammals, 8 birds, 5 fishes, 2 amphibians, 6 reptiles, and 12 invertebrates). Along with the permit application, Pima County submitted a draft Pima County Multi-Species Conservation Plan (MSCP). On June 10, 2015, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE) requested programmatic section 7 consultation for actions under section 404 of the Clean Water Act (CW A), including two Regional General Permits and 16 Nationwide Permits, that are also covered activities in the MSCP. This is an action under section 7 of the ESA that is separate from the section 10 permit issuance to Pima Couny. -

Coronado National Memorial Historical Research Project Research Topics Written by Joseph P. Sánchez, Ph.D. John Howard White

Coronado National Memorial Historical Research Project Research Topics Written by Joseph P. Sánchez, Ph.D. John Howard White, Ph.D. Edited by Angélica Sánchez-Clark, Ph.D. With the assistance of Hector Contreras, David Gómez and Feliza Monta University of New Mexico Graduate Students Spanish Colonial Research Center A Partnership between the University of New Mexico and the National Park Service [Version Date: May 20, 2014] 1 Coronado National Memorial Coronado Expedition Research Topics 1) Research the lasting effects of the expedition in regard to exchanges of cultures, Native American and Spanish. Was the shaping of the American Southwest a direct result of the Coronado Expedition's meetings with natives? The answer to this question is embedded throughout the other topics. However, by 1575, the Spanish Crown declared that the conquest was over and the new policy of pacification would be in force. Still, the next phase that would shape the American Southwest involved settlement, missionization, and expansion for valuable resources such as iron, tin, copper, tar, salt, lumber, etc. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado’s expedition did set the Native American wariness toward the Spanish occupation of areas close to them. Rebellions were the corrective to their displeasure over colonial injustices and institutions as well as the mission system that threatened their beliefs and spiritualism. In the end, a kind of syncretism and symbiosis resulted. Today, given that the Spanish colonial system recognized that the Pueblos and mission Indians had a legal status, land grants issued during that period protects their lands against the new settlement pattern that followed: that of the Anglo-American. -

The Trail Inventory of U.S

The Trail Inventory of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Stations in Arizona Prepared By: Federal Highway Administration Central Federal Lands Highway Division March 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE 1. AZ STATE SUMMARY Table of Contents 1-1 List of Refuges 1-2 Mileage by Trail Class, Condition, and Surface 1-3 2-9. REFUGE SUMMARIES Mileage by Trail Class, Condition, and Surface X-1 Trail Location Map X-2 Trail Identification X-3 Condition and Deficiency Sheets X-4 Photographic Sheets X-5 10. APPENDIX Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations 10-1 Trail Classification System 10-4 1-1 FWS Stations in Arizona with Trails Station Name Trail Miles Chapter Bill Williams River NWR 0.27 2 Buenos Aires NWR 6.62 3 Cabeza Prieta NWR 0.16 4 Cibola NWR 0.91 5 Havasu NWR 0.22 6 Imperial NWR 1.31 7 Leslie Canyon NWR 1.47 8 San Bernardino NWR 2.39 9 1-2 Arizona NWR Trail and Summaries Trail Miles and Percentages by Surface Type and Condition Mileage by Trail Condition Total Trail Surface Excellent Good Fair Poor Very Poor Not Rated* Miles Type MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % Native 7.91 59% 0.20 2% 0.32 2% 0% 0% 0% 8.43 Gravel 0.96 7% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.96 Asphalt 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.00 Concrete 0.27 2% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.27 Turnpike 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.00 Boardwalk 0.26 2% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.26 Puncheon 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.00 Woodchips 0.05 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.05 Admin Road 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 3.36 25% 3.36 Other 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.00 Totals 9.45 71% 0.20 2% 0.32 2% 0.00 0% 0.00 0% 3.36 25% 13.33 Trail Miles and Percentages by Trail Classification and Condition Mileage by Trail Condition Total Trail Excellent Good Fair Poor Very Poor Not Rated* Miles Classification MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % TC1 2.60 20% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 2.60 TC2 1.88 14% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 1.88 TC3 1.04 8% 0% 0.32 2% 0% 0% 0.97 7% 2.33 TC4 3.61 27% 0.20 2% 0% 0% 0% 2.39 18% 6.20 TC5 0.32 2% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.32 Totals 9.45 71% 0.20 2% 0.32 2% 0.00 0% 0.00 0% 3.36 25% 13.33 * Admin Roads are included in the inventory but are not rated for condition. -

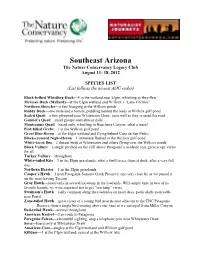

SPECIES LIST (List Follows the Newest AOU Order)

Southeast Arizona The Nature Conservancy Legacy Club August 11- 18, 2012 SPECIES LIST (List follows the newest AOU order) Black-bellied Whistling-Duck––4 in the wetland near Elgin, whistling as they flew Mexican Duck (Mallard)––at the Elgin wetland and Willcox’s “Lake Cochise” Northern Shoveler––a few lounging at the Willcox ponds Ruddy Duck––one male and a female, paddling behind the reeds at Willcox golf pond Scaled Quail––a few glimpsed near Whitewater Draw, seen well as they crossed the road Gambel’s Quail––small groups seen almost daily Montezuma Quail––heard only, whistling in Huachuca Canyon, what a tease! Pied-billed Grebe––1 at the Willcox golf pond Great Blue Heron––at the Elgin wetland and flying behind Casa de San Pedro Black-crowned Night-Heron––1 immature flushed at the Willcox golf pond White-faced Ibis––2 distant birds at Whitewater and others flying over the Willcox ponds Black Vulture––a single perched on the cliff above Patagonia’s roadside rest, great scope views for all. Turkey Vulture––throughout White-tailed Kite––3 in the Elgin grasslands, what a thrill to see them at dusk, after a very full day Northern Harrier––1 in the Elgin grasslands Cooper’s Hawk––1 near Patagonia-Sonoita Creek Preserve, one very close by as we passed it on the road leaving Tucson Gray Hawk––heard only in several locations in the lowlands. With ample time in two of its favorite haunts, we were surprised not to get “cracking” views. Swainson’s Hawk––fairly common along the roadsides on most days, particularly noticeable near Portal. -

Structure and Mineralization of the Oro Blanco Mining District, Santa Cruz County, Arizona

Structure and mineralization of the Oro Blanco Mining District, Santa Cruz County, Arizona Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Knight, Louis Harold, 1943- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 20:13:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565224 STRUCTURE AND MINERALIZATION OF THE ORO BLANCO MINING DISTRICT, SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, ARIZONA by * Louis Harold Knight, Jr. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 0 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Louis Harold Knight, Jr._______________________ entitled Structure and Mineralization of the Pro Blanco______ Mining District, Santa Cruz County, Arizona_________ be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy________________________________ a/akt/Z). m date ' After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:* SUtzo. /16? QJr zd /rtf C e f i, r --------- 7-------- /?S? This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate1s adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination. The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. -

USGS Open-File Report 2009-1269, Appendix 1

Appendix 1. Summary of location, basin, and hydrological-regime characteristics for U.S. Geological Survey streamflow-gaging stations in Arizona and parts of adjacent states that were used to calibrate hydrological-regime models [Hydrologic provinces: 1, Plateau Uplands; 2, Central Highlands; 3, Basin and Range Lowlands; e, value not present in database and was estimated for the purpose of model development] Average percent of Latitude, Longitude, Site Complete Number of Percent of year with Hydrologic decimal decimal Hydrologic altitude, Drainage area, years of perennial years no flow, Identifier Name unit code degrees degrees province feet square miles record years perennial 1950-2005 09379050 LUKACHUKAI CREEK NEAR 14080204 36.47750 109.35010 1 5,750 160e 5 1 20% 2% LUKACHUKAI, AZ 09379180 LAGUNA CREEK AT DENNEHOTSO, 14080204 36.85389 109.84595 1 4,985 414.0 9 0 0% 39% AZ 09379200 CHINLE CREEK NEAR MEXICAN 14080204 36.94389 109.71067 1 4,720 3,650.0 41 0 0% 15% WATER, AZ 09382000 PARIA RIVER AT LEES FERRY, AZ 14070007 36.87221 111.59461 1 3,124 1,410.0 56 56 100% 0% 09383200 LEE VALLEY CR AB LEE VALLEY RES 15020001 33.94172 109.50204 1 9,440e 1.3 6 6 100% 0% NR GREER, AZ. 09383220 LEE VALLEY CREEK TRIBUTARY 15020001 33.93894 109.50204 1 9,440e 0.5 6 0 0% 49% NEAR GREER, ARIZ. 09383250 LEE VALLEY CR BL LEE VALLEY RES 15020001 33.94172 109.49787 1 9,400e 1.9 6 6 100% 0% NR GREER, AZ. 09383400 LITTLE COLORADO RIVER AT GREER, 15020001 34.01671 109.45731 1 8,283 29.1 22 22 100% 0% ARIZ. -

Environmental Flows and Water Demands in Arizona

Environmental Flows and Water A University of Arizona Water Resources Research Center Project Demands in Arizona ater is an increasingly scarce resource and is essential for Arizona’s future. Figure 1. Elements of Environmental Flow WWith Arizona’s population growth and Occurring in Seasonal Hydrographs continued drought, citizens and water managers have been taking a closer look at water supplies in the state. Municipal, industrial, and agricul- tural water users are well-represented demand sectors, but water supplies and management to benefit the environment are not often consid- ered. This bulletin explains environmental water demands in Arizona and introduces information essential for considering environmental water demands in water management discussions. Considering water for the environment is impor- tant because humans have an interconnected and interdependent relationship with the envi- ronment. Nature provides us recreation oppor- tunities, economic benefits, and water supplies Data Source: to sustain our communities. USGS stream gage data Figure 2: Human Demand and Current Flow in Arizona Environmental water demands (or environmental flow) (circle size indicates relative amount of water) refers to how much water is needed in a watercourse to sustain a healthy ecosystem. Defining environmental water demand goes beyond the ecology and hydrol- Maximum ogy of a system and should include consideration for Flows how much water is required to achieve an agreed Industrial 40.8 maf Industrial SW Municipal upon level of river health, as determined by the GW 1% GW 8% water-using community. Arizona’s native ani- 4% mals and plants depend upon dynamic flows commonly described according to the natural Municipal SW flow regime. -

Cienegas Vanishing Climax Communities of the American

Hendrickson and Minckley Cienegas of the American Southwest 131 Abstract Cienegas The term cienega is here applied to mid-elevation (1,000-2,000 m) wetlands characterized by permanently saturated, highly organic, reducing soils. A depauperate Vanishing Climax flora dominated by low sedges highly adapted to such soils characterizes these habitats. Progression to cienega is Communities of the dependent on a complex association of factors most likely found in headwater areas. Once achieved, the community American Southwest appears stable and persistent since paleoecological data indicate long periods of cienega conditions, with infre- quent cycles of incision. We hypothesize the cienega to be an aquatic climax community. Cienegas and other marsh- land habitats have decreased greatly in Arizona in the Dean A. Hendrickson past century. Cultural impacts have been diverse and not Department of Zoology, well documented. While factors such as grazing and Arizona State University streambed modifications contributed to their destruction, the role of climate must also be considered. Cienega con- and ditions could be restored at historic sites by provision of ' constant water supply and amelioration of catastrophic W. L. Minckley flooding events. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Dexter Fish Hatchery Introduction and Department of Zoology Written accounts and photographs of early explorers Arizona State University and settlers (e.g., Hastings and Turner, 1965) indicate that most pre-1890 aquatic habitats in southeastern Arizona were different from what they are today. Sandy, barren streambeds (Interior Strands of Minckley and Brown, 1982) now lie entrenched between vertical walls many meters below dry valley surfaces. These same streams prior to 1880 coursed unincised across alluvial fills in shallow, braided channels, often through lush marshes. -

PETRIFIED FOREST: a Playground for Wildlife Baseball’S Back!

Spring PETRIFIED FOREST: A Playground for Wildlife Baseball’s Back! arizonahighways.com march 2003 MARCH 2003 page 50 COVER NATURE 55 GENE PERRET’S WIT STOP 6 14 If you’d like a good Surprise, drive northwest of Survival in the Grasslands A Bevy of Blooms Phoenix — and don’t ask Why. Preserving masked bobwhite quail and and Butterflies pronghorn antelope also rebuilds the habitat 44 HUMOR at Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge. Delicate-winged beauties and dazzling floral displays await at the Phoenix Desert Botanical 2 LETTERS AND E-MAIL Garden’s Butterfly Pavilion. 22 PORTFOLIO 46 DESTINATION Arizona’s in Love with INDIANS Lowell Observatory 18 Visitors get telescope time, too, at this noted Baseball Spring Training Butterfly Myths institution, home to 27 full-time astronomers doing pioneering research. The Cactus League’s 10 major league teams The gentle, fluttering insects take on varied have a devoted following, including visitors symbolic roles in many Indian cultures. 3 TAKING THE OFF-RAMP from out of state. Explore Arizona oddities, attractions and pleasures. HISTORY TRAVEL 32 54 EXPERIENCE ARIZONA 38 Hike a Historic Trail Go on a hike or pan for gold in Apache Junction to Life in a Stony Landscape Retrace the southern Arizona route of Spain’s commemorate treasure hunting in the Superstition Come spring, the Petrified Forest National Juan Bautista de Anza, who led the 18th-century Mountains; help the Tohono O’odham Indians celebrate Park is abuzz with critters and new plants. colonization of San Francisco. their heritage and see their arts and crafts in Ajo; and enjoy the re-enactment of mountain man skills in Oatman.