At Racing's Threshold 28

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

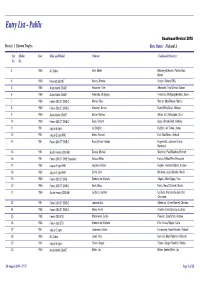

REV Entry List

Entry List - Public Goodwood Revival 2018 Race(s): 1 Kinrara Trophy - Race Status: National A Car Shelter Year Make and Model Entrant Confirmed Driver(s) No. No. 3 1963 AC Cobra Hunt, Martin Blakeney-Edwards, Patrick/Hunt, Martin 4 1960 Maserati 3500GT Rosina, Stefano Rosina, Stefano/TBC, 5 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Alexander, Tom Alexander, Tom/Wilmott, Adrian 6 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Friedrichs, Wolfgang Friedrichs, Wolfgang/Hadfield, Simon 7 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Werner, Max Werner, Max/Werner, Moritz 8 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Allemann, Benno Dowd, Mike/Gnani, Michael 9 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Mosler, Mathias Gillian, G.C./Woodgate, Chris 10 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Gaye, Vincent Gaye, Vincent/Reid, Anthony 11 1961 Jaguar E-type Ian Dalglish Dalglish, Ian/Turner, James 12 1961 Jaguar E-type FHC Meins, Richard Huff, Rob/Meins, Richard 14 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Racing Team Holland Hugenholtz, John/van Oranje, Bernhard 15 1961 Austin Healey 3000 Mk1 Darcey, Michael Woolmer, Paul/Woolmer, Richard 16 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB 'Breadvan' Halusa, Niklas Halusa, Niklas/Pirro, Emanuele 17 1962 Jaguar E-type FHC Hayden, Andrew Hayden, Andrew/Hibberd, Andrew 18 1962 Jaguar E-type FHC Corrie, John Minshaw, Jason/Stretton, Martin 19 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB Scuderia del Viadotto Vögele, Alain/Vögele, Yves 20 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Devis, Marc Devis, Marc/O'Connell, Martin 21 1960 Austin Healey 3000 Mk1 Le Blanc, Karsten Le Blanc, Karsten/van Lanschot, Christiaen 23 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Lanzante Ltd. Ellerbrock, Olivier/Glaesel, Christian -

Preserving the Automobile: an Auction at the Simeone

PRESERVING THE AUTOMOBILE: AN AUCTION AT THE SIMEONE FOUNDATION AUTOMOTIVE MUSEUM Monday October 5, 2015 The Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum Philadelphia, Pennsylvania PRESERVING THE AUTOMOBILE: AN AUCTION AT THE SIMEONE FOUNDATION AUTOMOTIVE MUSEUM Monday October 5, 2015 Automobilia 11am Motorcars 2pm Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum Philadelphia, Pennsylvania PREVIEW & AUCTION LOCATION INQUIRIES BIDS Simeone Foundation Automotive Eric Minoff +1 (212) 644 9001 Museum +1 (917) 206 1630 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax 6825-31 Norwitch Drive [email protected] Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19153 From October 2-7, to reach us Rupert Banner directly at the Simeone Foundation PREVIEW +1 (917) 340 9652 Automotive Museum: Saturday October 3, 10am to 5pm [email protected] +1 (415) 391 4000 Sunday October 4, 10am to 5pm +1 (415) 391 4040 fax Monday October 5, Motorcars only Evan Ide from 9am to 2pm +1 (917) 340 4657 Automated Results Service [email protected] +1 (800) 223 2854 AUCTION TIMES Monday October 5 Jakob Greisen Online bidding will be available for Automobilia 11am +1 (415) 480 9028 this auction. For further information Motorcars 2pm [email protected] please visit: www.bonhams.com/simeone Mark Osborne +1 (415) 503 3353 SALE NUMBER: 22793 [email protected] Lots 1 - 276 General Information and Please see pages 2 to 7 for Automobilia Inquiries bidder information including Samantha Hamill Conditions of Sale, after-sale +1 (212) 461 6514 collection and shipment. +1 (917) 206 1669 fax [email protected] ILLUSTRATIONS Front cover: Lot 265 Vehicle Documents First session page: Lot 8 Veronica Duque Second session page: Lot 254 +1 (415) 503 3322 Back cover: Lots 257, 273, 281 [email protected] and 260 © 2015, Bonhams & Butterfields Auctioneers Corp.; All rights reserved. -

Barney Oldfield the Life and Times of America’S Legendary Speed King

Barney Oldfield The Life and Times of America’s Legendary Speed King Revised, Expanded Edition by William F. Nolan Brown Fox TM Books C A R P I N T E R I A C A L I F O R N I A Published by Brown Fox Books, Carpinteria, California ISBN 1-888978-12-0 ISBN 1-888978-13-0 Limited edition, leather binding First published in 1961 by G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York Copyright © 1961 by William F. Nolan. Copyright © renewed 1989 by William F. Nolan. All new text in this edition Copyright © 2002 by William F. Nolan. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, with the exception of quoting brief passages for purpose of review. Requests for permissions should be addressed to the publisher: Brown Fox Books 1090 Eugenia Place Carpinteria, California 93013 Tel: 1-805-684-5951 Email: [email protected] www.BrownFoxBooks.com Second Edition—revised Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nolan, William F., 1928- Barney Oldfield : the life and times of America’s legendary speed king / William F. Nolan.—Rev., expanded ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-888978-12-0 1. Oldfield, Barney, 1878-1946. 2. Automobile racing drivers— United States—Biography. I. Title. GV 1032.04 N6 2002 796.72’092—dc21 [B] 2002027845 Body type is set in Electra; titles and photo captions are Serifa; index and tables are set in Stone Sans. -

1911: All 40 Starters

INDIANAPOLIS 500 – ROOKIES BY YEAR 1911: All 40 starters 1912: (8) Bert Dingley, Joe Horan, Johnny Jenkins, Billy Liesaw, Joe Matson, Len Ormsby, Eddie Rickenbacker, Len Zengel 1913: (10) George Clark, Robert Evans, Jules Goux, Albert Guyot, Willie Haupt, Don Herr, Joe Nikrent, Theodore Pilette, Vincenzo Trucco, Paul Zuccarelli 1914: (15) George Boillot, S.F. Brock, Billy Carlson, Billy Chandler, Jean Chassagne, Josef Christiaens, Earl Cooper, Arthur Duray, Ernst Friedrich, Ray Gilhooly, Charles Keene, Art Klein, George Mason, Barney Oldfield, Rene Thomas 1915: (13) Tom Alley, George Babcock, Louis Chevrolet, Joe Cooper, C.C. Cox, John DePalma, George Hill, Johnny Mais, Eddie O’Donnell, Tom Orr, Jean Porporato, Dario Resta, Noel Van Raalte 1916: (8) Wilbur D’Alene, Jules DeVigne, Aldo Franchi, Ora Haibe, Pete Henderson, Art Johnson, Dave Lewis, Tom Rooney 1919: (19) Paul Bablot, Andre Boillot, Joe Boyer, W.W. Brown, Gaston Chevrolet, Cliff Durant, Denny Hickey, Kurt Hitke, Ray Howard, Charles Kirkpatrick, Louis LeCocq, J.J. McCoy, Tommy Milton, Roscoe Sarles, Elmer Shannon, Arthur Thurman, Omar Toft, Ira Vail, Louis Wagner 1920: (4) John Boling, Bennett Hill, Jimmy Murphy, Joe Thomas 1921: (6) Riley Brett, Jules Ellingboe, Louis Fontaine, Percy Ford, Eddie Miller, C.W. Van Ranst 1922: (11) E.G. “Cannonball” Baker, L.L. Corum, Jack Curtner, Peter DePaolo, Leon Duray, Frank Elliott, I.P Fetterman, Harry Hartz, Douglas Hawkes, Glenn Howard, Jerry Wonderlich 1923: (10) Martin de Alzaga, Prince de Cystria, Pierre de Viscaya, Harlan Fengler, Christian Lautenschlager, Wade Morton, Raoul Riganti, Max Sailer, Christian Werner, Count Louis Zborowski 1924: (7) Ernie Ansterburg, Fred Comer, Fred Harder, Bill Hunt, Bob McDonogh, Alfred E. -

Download Gesamter Artikel

Die Legende: Mercedes 300 SL Mercedes-Benz W 198 ist die interne Typbezeichnung eines Sportwagens von Mercedes- Benz. Unter der Verkaufsbezeichnung Mercedes 300 SL wurde er in den Jahren 1954 bis 1957 als Coupé mit Flügeltüren und in den Jahren 1957 bis 1963 als Roadster angeboten. Die Zahl 300 steht in der Verkaufsbezeichnung für ein Zehntel des Hubraums in Kubikzentimeter gemessen, die Zusatzbezeichnung SL soll die Kurzform für „Sport Leicht“ sein, andere Quellen geben „Super Leicht“ als Langform an. Mercedes-Benz präsentierte den 300 SL im Februar 1954 auf der International Motor Sports Show in New York. 1999 wurde das Fahrzeug von Lesern der deutschen Oldtimer-Zeitschrift Motor Klassik zum „Sportwagen des Jahrhunderts“ gewählt. Vorgängerversion im Motorsport Mercedes-Benz 300 SL W 194 von 1952 beim Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 1986 auf dem Nürburgring. Die Gitterstäbe vor der Frontscheibe wurden nach dem Einschlag eines Geiers in Mexiko angebracht. Der Original-300-SL, der Rennsportwagen Mercedes-Benz W 194, errang im Jahre 1952 unerwartete Erfolge. Im Vorjahr fiel bei der Daimler-Benz AG die Entscheidung, 1952 wieder an Rennen teilzunehmen und hierfür einen Sportwagen zu bauen. Dieser erhielt den Namen „300 Sport Leicht“. Um eine für Rennen ausreichende Leistung zu erreichen, musste der vorhandene Motor der Limousine 300 (Adenauer) weiterentwickelt werden. Noch mit Vergasern bestückt, leistete dieser mit 129 kW (175 PS) deutlich weniger als die Straßenversion von 1954. 1952 nahm das Fahrzeug an den wichtigen Rennen des Jahres teil, gegen deutlich stärker motorisierte Gegner. Erstmals hatte der neue SL bei der Mille Miglia Anfang Mai Geschwindigkeit und Zuverlässigkeit gezeigt und in diesem Langstreckenrennen den zweiten Platz erzielt. -

Harvest Classic

through the years A FORGOTTEN The Allstate 400 at the Brickyard instantly became one of the premier events in motorsports when it was introduced in 1994. But long before NASCAR arrived at the Speedway, even long before NASCAR was founded, the Brickyard hosted another major event other than the Indy 500. Named the Harvest Auto Racing Classic, it wrote an obscure chapter in With war already raging in Speedway history 90 years ago in September 1916. Europe and U.S. involvement imminent, a series of races were scheduled at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway by Mark Dill for late summer 1916. illustrations by Gregory R. Beall 151 through the years A FORGOTTEN The Allstate 400 at the Brickyard instantly became one of the premier events in motorsports when it was introduced in 1994. But long before NASCAR arrived at the Speedway, even long before NASCAR was founded, the Brickyard hosted another major event other than the Indy 500. Named the Harvest Auto Racing Classic, it wrote an obscure chapter in With war already raging in Speedway history 90 years ago in September 1916. Europe and U.S. involvement imminent, a series of races were scheduled at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway by Mark Dill for late summer 1916. illustrations by Gregory R. Beall 151 through the years Originally, 20 cars were entered for the Harvest driver to race one of the Speedway’s Peugeots. Classic, but the attrition at Cincinnati took its Dario Resta, who in May won the only Indy toll and by race day the field had dwindled to 14. -

ACES WILD ACES WILD the Story of the British Grand Prix the STORY of the Peter Miller

ACES WILD ACES WILD The Story of the British Grand Prix THE STORY OF THE Peter Miller Motor racing is one of the most 10. 3. BRITISH GRAND PRIX exacting and dangerous sports in the world today. And Grand Prix racing for Formula 1 single-seater cars is the RIX GREATS toughest of them all. The ultimate ambition of every racing driver since 1950, when the com petition was first introduced, has been to be crowned as 'World Cham pion'. In this, his fourth book, author Peter Miller looks into the back ground of just one of the annual qualifying rounds-the British Grand Prix-which go to make up the elusive title. Although by no means the oldest motor race on the English sporting calendar, the British Grand Prix has become recognised as an epic and invariably dramatic event, since its inception at Silverstone, Northants, on October 2nd, 1948. Since gaining World Championship status in May, 1950 — it was in fact the very first event in the Drivers' Championships of the W orld-this race has captured the interest not only of racing enthusiasts, LOONS but also of the man in the street. It has been said that the supreme test of the courage, skill and virtuosity of a Grand Prix driver is to w in the Monaco Grand Prix through the narrow streets of Monte Carlo and the German Grand Prix at the notorious Nürburgring. Both of these gruelling circuits cer tainly stretch a driver's reflexes to the limit and the winner of these classic events is assured of his rightful place in racing history. -

Karl E. Ludvigsen Papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26

Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Miles Collier Collections Page 1 of 203 Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Title: Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Creator: Ludvigsen, Karl E. Call Number: Archival Collection 26 Quantity: 931 cubic feet (514 flat archival boxes, 98 clamshell boxes, 29 filing cabinets, 18 record center cartons, 15 glass plate boxes, 8 oversize boxes). Abstract: The Karl E. Ludvigsen papers 1905-2011 contain his extensive research files, photographs, and prints on a wide variety of automotive topics. The papers reflect the complexity and breadth of Ludvigsen’s work as an author, researcher, and consultant. Approximately 70,000 of his photographic negatives have been digitized and are available on the Revs Digital Library. Thousands of undigitized prints in several series are also available but the copyright of the prints is unclear for many of the images. Ludvigsen’s research files are divided into two series: Subjects and Marques, each focusing on technical aspects, and were clipped or copied from newspapers, trade publications, and manufacturer’s literature, but there are occasional blueprints and photographs. Some of the files include Ludvigsen’s consulting research and the records of his Ludvigsen Library. Scope and Content Note: The Karl E. Ludvigsen papers are organized into eight series. The series largely reflects Ludvigsen’s original filing structure for paper and photographic materials. Series 1. Subject Files [11 filing cabinets and 18 record center cartons] The Subject Files contain documents compiled by Ludvigsen on a wide variety of automotive topics, and are in general alphabetical order. -

Nuevo Mondeo Vignale Híbrido | Manual Del Propietario

FORD MONDEO VIGNALE Manual del Propietario La información presentada en esta publicación era correcta al momento de la impresión. Para asegurar un continuo desarrollo, nos reservamos el derecho de modificar especificaciones, diseño o equipo en cualquier momento y sin previo aviso ni obligación. Ninguna parte de esta publicación puede ser reproducida, transmitida, almacenada en un sistema de recuperación o traducida a otro idioma, de ninguna forma y por ningún medio, sin nuestra autorización por escrito. Se exceptúan los errores y las omisiones. © Ford Motor Company 2018 Todos los derechos reservados. Número de pieza: CG3821esARG 201812 20181210162319 Contenido Introducción Cinturones de seguridad Comprobación del estado del sistema MyKey ................................................................48 Reconocimientos ..................................................7 Modo de abrocharse los cinturones de seguridad ..........................................................35 Uso de MyKey con sistemas de arranque Acerca de este manual .......................................7 remotos .............................................................48 Glosario de símbolos ...........................................7 Ajuste de la altura de los cinturones de seguridad ..........................................................36 MyKey – Solución de problemas .................48 Grabación de datos .............................................9 Recordatorio de cinturones de seguridad Recomendación de las piezas de repuesto ...............................................................................36 -

Sports Racing Cars 1938 – 1957

Sports Racing Cars 1938 – 1957 Abarth Spyder Ferrari 166 MM Barchetta Touring Lister - Corvette Adler Trumpf Rennlimousine Ferrari 166 MM Berlinetta Touring LM Lister - Jaguar Aero Minor Sport Ferrari 166 MM/53 Spider Vignale Lister - MG Alfa Romeo 1900 Ferrari 166 S Coupé Allemano Lotus Eleven Alfa Romeo 1900 Sprint Coupé Touring Ferrari 166 SC Lotus Eleven Climax Alfa Romeo 1900 SS Zagato Ferrari 195 Inter Berlinetta Motto Lotus Mark IX Climax Alfa Romeo 1900 TI Ferrari 195 S Barchetta Fontana Magda Alfa Romeo 412 Spider Vignale Ferrari 195 S Barchetta Touring Maserati 150S Alfa Romeo 6C 2300 Pescara Spider Zagato Ferrari 212 Export Barchetta Maserati 200S Alfa Romeo 6C 2500 Ferrari 212 Export Berlinetta Vignale Maserati 200SI Alfa Romeo 6C 2500 'Freccia d'Oro' Ferrari 212 Export Spider Motto Maserati 300S Alfa Romeo 6C 2500 Competizione Berlinetta Ferrari 250 GT LWB Scaglietti Maserati 300S Fantuzzi Alfa Romeo 6C 2500 SS Ferrari 250 GT LWB Zagato Maserati 450S Alfa Romeo 6C 2500 SS Berlinetta Touring Ferrari 250 MM Pinin Farina Maserati A6GCS Alfa Romeo 6C 2500 SS Coupé Touring Ferrari 250 MM Spider Vignale Maserati A6GCS/53 Alfa Romeo 6C 2500 SS Spider Ferrari 250 Monza Maserati A6GCS/53 Fantuzzi Alfa Romeo 6C 2500 SS Spider Touring Ferrari 250 S Berlinetta Vignale Mercedes-Benz 220A Alfa Romeo 6C 3000 CM Berlinetta Colli Ferrari 290 MM Mercedes-Benz 300 SL Alfa Romeo 6C Spider Zagato Ferrari 290 MM Scaglietti Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 Monza Ferrari 315 Sport MG Alfa Romeo 8C 2300A Ferrari 335 Sport MG EX182 Alfa Romeo -

Strangest Races

MOTOR-RACING’S STRANGEST RACES Extraordinary but true stories from over a century of motor-racing GEOFF TIBBALLS Motor-racing’s Strangest Races Other titles in this series Boxing’s Strangest Fights Cricket’s Strangest Matches Football’s Strangest Matches Golf’s Strangest Rounds Horse-Racing’s Strangest Races Rugby’s Strangest Matches Tennis’s Strangest Matches Motor-racing’s Strangest Races GEOFF TIBBALLS Robson Books First published in Great Britain in 2001 by Robson Books, 10 Blenheim Court, Brewery Road, London N7 9NY Reprinted 2002 A member of the Chrysalis Group pic Copyright © 2001 Geoff Tibballs The right of Geoff Tibballs to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The author and the publishers have made every reasonable effort to contact all copyright holders. Any errors that may have occurred are inadvertent and anyone who for any reason has not been contacted is invited to write to the publishers so that a full acknowledgement may be made in subsequent editions of this work. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 86105 411 4 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publishers. Produced by Sino Publishing House Ltd, Hong Kong CONTENTS Acknowledgements -

Unveils Ford Mondeo Vignale Concept

NEWS Ford Introduces Unique ‘Vignale’ Product and Ownership Experience in Europe; Unveils Ford Mondeo Vignale Concept • Ford of Europe plans to launch Vignale – a unique upscale product and ownership experience – in early 2015 • New Ford Mondeo Vignale Concept provides a first look at the vision for Vignale, including unique interior and exterior design touches, premium craftsmanship, exclusive specification and technologies • Ford Mondeo Vignale Concept includes special 20-inch alloy wheels; chrome detailing; unique front bumper, fog lamp and grille design; quilted, premium leather seats; and an exclusive Vignale colour, “Nocciola” • Ford’s vision for the Vignale retail experience includes services such as collection and delivery for vehicle servicing, free lifetime carwashes and invitations to special events • The first new Ford Vignale model will be based on the all-new Mondeo with other Vignale models coming soon to Europe LOMMEL, Belgium, Oct. 8, 2013 – Ford Motor Company plans to launch a unique upscale product and ownership experience in Europe called Vignale. Ford provided a glimpse of its vision for Vignale (pronounced: Vin-ya-le) with the Ford Mondeo Vignale Concept, which offers unique design touches, high quality craftsmanship, exclusive specification and advanced technologies. “Vignale will offer the highest expression of the Ford brand in Europe from a product and from an ownership experience perspective,” said Stephen Odell, Ford’s president of Europe, Middle East and Africa. “The Ford Mondeo Vignale Concept showcases the features that customers tell us they want in terms of styling and quality, advanced technology and exclusivity.” Ford chose to present the new Ford Mondeo Vignale Concept with an exclusive and sophisticated four-door saloon body style, and also as a wagon; both featuring 20-inch Vignale alloy wheels with in-depth detailing and high-quality finish, “Vignale” badging, chrome door handles and mirror caps, mesh grille, unique front bumper and fog lamp design, and exclusive “Nocciola” paint colour.