Strangest Races

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WRC Rallye D'espagne

MEDIA INFORMATION November 2013 2013 FIA World Endurance Championship Round 7: 6 Hours of Shanghai Victory for the N°1 AUDI R18 e-tron quattro/MICHELIN, as Tom Kristensen/Loïc Duval/Allan McNish secure the 2013 WEC Drivers’ title After the torrential rain that forced the organisers to halt the recent 6 Hours of Fuji after just 16 laps, all spent behind the safety car, Audi Sport Team Joest and Toyota Motorsport GmbH were both eager to join battle once again this weekend in China. In contrast to the conditions encountered in Japan, the 6 Hours of Shanghai was marked by clear skies and warm weather (air temperature: approximately 25°C, and track temperatures up to 30°C) which enabled the teams to produce yet another thrilling show, with the outcome only settled with less than half-an-hour remaining. The pole-winning N°7 Toyota TS030-Hybrid of Wurz/Lapierre carved out an early lead, while the N°8 sister car – with Antony Davidson in command – engaged in a fight with André Lotterer in the N°1 Audi R18 e-tron quattro. On Lap 10, the British driver succeeded in finding a way past to ease into second place. The two Japanese prototypes then proceeded to dominate the top of the leaderboard until the eventful 143rd lap (190 laps completed in total). After 4½ hours of racing, the N°8 Toyota TS030-Hybrid was suddenly eliminated when its front- right suspension failed under barking for Turn 6. This promoted the N°1 Audi to second spot, approximately half-a-minute behind the N°7 Toyota, thanks to a strong stint from Benoît Tréluyer in the German car, as well as to a couple of time-consuming „moments‟ for the Japanese team‟s Nicolas Lapierre while overtaking slower competitors. -

Hitlers GP in England.Pdf

HITLER’S GRAND PRIX IN ENGLAND HITLER’S GRAND PRIX IN ENGLAND Donington 1937 and 1938 Christopher Hilton FOREWORD BY TOM WHEATCROFT Haynes Publishing Contents Introduction and acknowledgements 6 Foreword by Tom Wheatcroft 9 1. From a distance 11 2. Friends - and enemies 30 3. The master’s last win 36 4. Life - and death 72 5. Each dangerous day 90 6. Crisis 121 7. High noon 137 8. The day before yesterday 166 Notes 175 Images 191 Introduction and acknowledgements POLITICS AND SPORT are by definition incompatible, and they're combustible when mixed. The 1930s proved that: the Winter Olympics in Germany in 1936, when the President of the International Olympic Committee threatened to cancel the Games unless the anti-semitic posters were all taken down now, whatever Adolf Hitler decrees; the 1936 Summer Games in Berlin and Hitler's look of utter disgust when Jesse Owens, a negro, won the 100 metres; the World Heavyweight title fight in 1938 between Joe Louis, a negro, and Germany's Max Schmeling which carried racial undertones and overtones. The fight lasted 2 minutes 4 seconds, and in that time Louis knocked Schmeling down four times. They say that some of Schmeling's teeth were found embedded in Louis's glove... Motor racing, a dangerous but genteel activity in the 1920s and early 1930s, was touched by this, too, and touched hard. The combustible mixture produced two Grand Prix races at Donington Park, in 1937 and 1938, which were just as dramatic, just as sinister and just as full of foreboding. This is the full story of those races. -

Maserati 100 Años De Historia 100 Years of History

MUNDO FRevista oficialANGIO de la Fundación Juan Manuel Fangio MASERATI 100 AÑOS DE HISTORIA 100 YEARS OF HISTORY FANGIO LA CARRERA Y EL Destinos / Destination DEPORTISTA DEL SIGLO MODENA THE RACE AND THE Autos / Cars SPORTSMAN OF THE CENTURY MASERATI GRANCABRIO SPORT Entrevista / Interview Argentina $30 ERMANNO COZZA TESTORELLI 1887 TAG HEUER FORMULA 1 CALIBRE 16 Dot Baires Shopping By pushing you to the limit and breaking all boundaries, Formula 1 is more La Primera Boutique de TAG HEUER than just a physical challenge; it is a test of mental strength. Like TAG Heuer, en Latinoamérica you have to strive to be the best and never crack under pressure. TESTORELLI 1887 TAG HEUER FORMULA 1 CALIBRE 16 Dot Baires Shopping By pushing you to the limit and breaking all boundaries, Formula 1 is more La Primera Boutique de TAG HEUER than just a physical challenge; it is a test of mental strength. Like TAG Heuer, en Latinoamérica you have to strive to be the best and never crack under pressure. STAFF SUMARIO Dirección Editorial: Fundación Museo Juan Manuel Fangio. CONTENTS Edición general: Gastón Larripa 25 Editorial Redacción: Rodrigo González 6 Editorial Colaboran en este número: Daniela Hegua, Néstor Pionti, Laura González, Lorena Frances- Los autos Maserati que corrió Fangio chetti, Mariana González, Maxi- 8 Maserati Race Cars Driven By Fangio miliano Manzón, Nancy Segovia, Mariana López. Diseño y diagramación: Cynthia Aniversario Fundación J.M. Fangio Larocca 16 Fangio museum’s Anniverasry Fotografía: Matías González 100 años de Maserati Archivo fotográfico: Fundación Museo Juan Manuel Fangio 18 100 years of Maserati Traducción: Romina Molachino Destinos: Modena Corrección: Laura González 26 Destinations: Modena Impresión: Ediciones Emede S.A. -

Prestone Ebook Winter Driving 3

A Prestone ebook: WINTER DRIVING Of all the seasons, winter creates the most challenging driving conditions, and can be extremely tough on your car. Treacherous weather coupled with dark evenings can make driving hazardous, so it’s vital you ready yourself and your car before the season takes hold. From heavy rain to ice and snow, winter will throw all sorts of extreme weather your way — so it’s best to be prepared. By checking the condition of your car and changing your driving style to adapt to the hazardous conditions, you can keep driving no matter how extreme the weather becomes. To help you stay safe behind the wheel this season, here’s an in-depth guide on the dos and don’ts of winter driving. From checking your vehicle’s coolant/antifreeze to driving in thick fog, heavy rain and high winds — this guide is packed with tips and advice on driving in even the most extreme winter weather. PREPARING YOUR VEHICLE FOR WINTER DRIVING Keeping your car in a good, well maintained condition is important throughout the year, but especially so in winter. At a time when extreme weather can strike at any moment, your car needs to be prepared and ready for the worst. The following checks will help to make sure your car is ready for even the toughest winter conditions. COOLANT / ANTIFREEZE Whatever the weather, your car needs coolant/antifreeze all year round to make sure the engine doesn’t overheat or freeze up. By adding a quality coolant/antifreeze to your engine, it’ll be protected in all extremes — from -37°C to 129°C and you’ll also be protected against corrosion. -

Alo-Decals-Availability-And-Prices-2020-06-1.Pdf

https://alodecals.wordpress.com/ Contact and orders: [email protected] Availability and prices, as of June 1st, 2020 Disponibilité et prix, au 1er juin 2020 N.B. Indicated prices do not include shipping and handling (see below for details). All prices are for 1/43 decal sets; contact us for other scales. Our catalogue is normally updated every month. The latest copy can be downloaded at https://alodecals.wordpress.com/catalogue/. N.B. Les prix indiqués n’incluent pas les frais de port (voir ci-dessous pour les détails). Ils sont applicables à des jeux de décalcomanies à l’échelle 1:43 ; nous contacter pour toute autre échelle. Notre catalogue est normalement mis à jour chaque mois. La plus récente copie peut être téléchargée à l’adresse https://alodecals.wordpress.com/catalogue/. Shipping and handling as of July 15, 2019 Frais de port au 15 juillet 2019 1 to 3 sets / 1 à 3 jeux 4,90 € 4 to 9 sets / 4 à 9 jeux 7,90 € 10 to 16 sets / 10 à 16 jeux 12,90 € 17 sets and above / 17 jeux et plus Contact us / Nous consulter AC COBRA Ref. 08364010 1962 Riverside 3 Hours #98 Krause 4.99€ Ref. 06206010 1963 Canadian Grand Prix #50 Miles 5.99€ Ref. 06206020 1963 Canadian Grand Prix #54 Wietzes 5.99€ Ref. 08323010 1963 Nassau Trophy Race #49 Butler 3.99€ Ref. 06150030 1963 Sebring 12 Hours #11 Maggiacomo-Jopp 4.99€ Ref. 06124010 1964 Sebring 12 Hours #16 Noseda-Stevens 5.99€ Ref. 08311010 1965 Nürburgring 1000 Kms #52 Sparrow-McLaren 5.99€ Ref. -

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia Tyre Safety Report Op the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Road Sa

THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA TYRE SAFETY REPORT OP THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEE ON ROAD SAFETY JUNE 1980 AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING SERVICE CANBERRA 1980 © Commonwealth of Australia 1980 ISBN 0 642 04871 1 Printed by C. I THOMPSON, Commonwealth Govenimeat Printer, Canberra MEMBERSHIP OF THE COMMITTEE IN THE THIRTY-FIRST PARLIAMENT Chairman The Hon. R.C. Katter, M.P, Deputy Chai rman The Hon. C.K. Jones, M.P. Members Mr J.M. Bradfield, M.P. Mr B.J. Goodluck, M.P. Mr B.C. Humphreys, M.P. Mr P.F. Johnson, M.P. Mr P.F. Morris, M.P. Mr J.R. Porter, M.P. Clerk to the Committee Mr W. Mutton* Advisers to the Committee Mr L. Austin Mr M. Rice Dr P. Sweatman Mr Mutton replaced Mr F.R. Hinkley as Clerk to the Committee on 7 January 1980. (iii) CONTENTS Chapter Page Major Conclusions and Recommendations ix Abbreviations xvi i Introduction ixx 1 TYRES 1 The Tyre Market 1 -Manufacturers 1 Passenger Car Tyres 1 Motorcycle Tyres 2 - Truck and Bus Tyres 2 ReconditionedTyi.es 2 Types of Tyres 3 -Tyre Construction 3 -Tread Patterns 5 Reconditioned Tyres 5 The Manufacturing Process 7 2 TYRE STANDARDS 9 Design Rules for New Passenger Car Tyres 9 Existing Design Rules 9 High Speed Performance Test 10 Tests under Conditions of Abuse 11 Side Forces 11 Tyre Sizes and Dimensions 12 -Non-uniformity 14 Date of Manufacture 14 Safety Rims for New Passenger Cars 15 Temporary Spare Tyres 16 Replacement Passenger Car Tyres 17 Draft Regulations 19 Retreaded Passenger Car Tyres 20 Tyre Industry and Vehicle Industry Standards 20 -

19 June 2014 Maserati Centennial Exhibition Inaugurated in Modena

Date: 19 June 2014 Maserati Centennial Exhibition Inaugurated In Modena New exhibition retraces a century of Maserati at the spectacular Enzo Ferrari Museum (MEF). The unique exhibition hosts a priceless collection of historic models and gives visitors the opportunity to relive the history of Maserati through technology that transports you to the heart of the event. A unique exhibition dedicated to the Centennial of Maserati was inaugurated in Modena this morning. MASERATI 100 - A Century of Pure Italian Luxury Sports Cars retraces the story of the Italian car manufacturer through an exhibition featuring some of the Trident marque’s most significant road and racing cars, plus a highly engaging show employing 19 projectors, enabling visitors to relive the most significant moments in the history of Maserati and to learn about the individuals who shaped its history. Staged in the futuristic Enzo Ferrari Museum, a stone's throw from the Maserati headquarters in Viale Ciro Menotti, the exhibition will run until January 2015. Considering the historic value of the models exhibited, this is the greatest exhibition of Maserati cars ever staged anywhere in the world. The inauguration of the new exhibition was attended by the CEO of Maserati, Harald Wester, and the Chairman of Ferrari, Luca Cordero di Montezemolo. They were joined by the cousins Carlo and Alfieri Maserati, sons, respectively, of Ettore and Ernesto Maserati, the two brothers who in 1914, together with Alfieri Maserati, founded the company that still bears their name today. The guest of honour at the inauguration was the legendary Sir Stirling Moss, the 1950s Maserati racing driver who scooped incredible victories for the Trident marque. -

BRDC Bulletin

BULLETIN BULLETIN OF THE BRITISH RACING DRIVERS’ CLUB DRIVERS’ RACING BRITISH THE OF BULLETIN Volume 30 No 2 • SUMMER 2009 OF THE BRITISH RACING DRIVERS’ CLUB Volume 30 No 2 2 No 30 Volume • SUMMER 2009 SUMMER THE BRITISH RACING DRIVERS’ CLUB President in Chief HRH The Duke of Kent KG Volume 30 No 2 • SUMMER 2009 President Damon Hill OBE CONTENTS Chairman Robert Brooks 04 PRESIDENT’S LETTER 56 OBITUARIES Directors 10 Damon Hill Remembering deceased Members and friends Ross Hyett Jackie Oliver Stuart Rolt 09 NEWS FROM YOUR CIRCUIT 61 SECRETARY’S LETTER Ian Titchmarsh The latest news from Silverstone Circuits Ltd Stuart Pringle Derek Warwick Nick Whale Club Secretary 10 SEASON SO FAR 62 FROM THE ARCHIVE Stuart Pringle Tel: 01327 850926 Peter Windsor looks at the enthralling Formula 1 season The BRDC Archive has much to offer email: [email protected] PA to Club Secretary 16 GOING FOR GOLD 64 TELLING THE STORY Becky Simm Tel: 01327 850922 email: [email protected] An update on the BRDC Gold Star Ian Titchmarsh’s in-depth captions to accompany the archive images BRDC Bulletin Editorial Board 16 Ian Titchmarsh, Stuart Pringle, David Addison 18 SILVER STAR Editor The BRDC Silver Star is in full swing David Addison Photography 22 RACING MEMBERS LAT, Jakob Ebrey, Ferret Photographic Who has done what and where BRDC Silverstone Circuit Towcester 24 ON THE UP Northants Many of the BRDC Rising Stars have enjoyed a successful NN12 8TN start to 2009 66 MEMBER NEWS Sponsorship and advertising A round up of other events Adam Rogers Tel: 01423 851150 32 28 SUPERSTARS email: [email protected] The BRDC Superstars have kicked off their season 68 BETWEEN THE COVERS © 2009 The British Racing Drivers’ Club. -

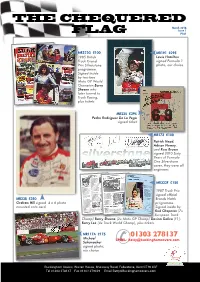

The Chequered Flag

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

90Th Anniversary of the Targa Florio Victory: Bugatti Wins Fifth Consecutive Title

90th anniversary of the Targa Florio victory: Bugatti wins fifth consecutive title MOLSHEIM 02 05 2019 FOR MANY YEARS BUGATTI DOMINATED THE MOST IMPORTANT CAR RACE OF THE 1920S Legends were born on this track. Targa Florio in Sicily was considered the world’s hardest, most prestigious and most dangerous long-distance race for many years. Today, current Bugatti models remind us of the drivers from back in the day. Sicilian entrepreneur Vincenzo Florio established his own race on family-owned roads in the Madonie region. Between 1906 and 1977, sports cars raced for the title at international races, some of which even had sports car world championship status. Winners at this race could proudly advertise their victory. For this reason, all important sports car manufacturers sent their vehicles to Sicily. Between 1925 and 1929 Bugatti dominated the race with the Type 35. In particular, in 1928 and 1929, one man showcased his skills at the wheel of his vehicle: Albert Divo. In these two years he was unbeatable in his Bugatti Type 35 C, winning the race in Sicily on 5 May 1929 after having also claimed the top spot in 1928. He also set a further record when he crossed the finish line: the “Fabrik Bugatti” team won the title five times in a row – this had never been done before in the history of the Targa Florio and remained an unbeaten record until the end of the last official races, to this day. A reason to look back. After all, the race was anything but easy: initially one lap of the “Piccolo circuito delle Madonie” was around 148 kilometres, from 1919 organisers cut the race lap distance to a still considerable 108 kilometres. -

Vzhůru Na Klausen Tvořila Jména, Která Se Navždy Zapsala Do Historie Motorismu

Švýcarská pohoda. Sluníčko, hory, auta a motocykly... Bugatti 35 bylo v roce 1925 na závod přihlášeno továrnou Ettora Bugattiho. Na 16. závod Historie Targa Florio přihlásil Ettore Bugatti tři závodní vozy a mezi nimi byl i tento automobil V alpských kulisách sedla Klausen se s číslem podvozku 4516. Pierre de Vizcaya s ním dojel celkově na čtvrtém místě. Ve čtyřech v letech 1922 až 1934 odehrávaly drama- následujících letech vyhrávaly legendární Targa Florio tovární vozy Bugatti a legendou se tické souboje mezi slavnými postavami stal i závodní vůz Bugatti 35. Na Klausenpassu jel v roce 1925 s bugatkou Mario Lepori. motoristického sportu a Klausenren- Časem 18:25,20 skončil čtvrtý v kategorii závodních vozů a 3. v kategorii 1501–2000 ccm. nen se stal právem jedním z nejdůležitěj- Dnešním majitelem speciálu postaveného pro Targa Florio je Christoph Ringier ších evropských závodů mezi světovými válkami. Seznam startujících na tomto po celé Evropě proslaveném závodu do vrchu Vzhůru na Klausen tvořila jména, která se navždy zapsala do historie motorismu. O vítězství usilovali Závody do vrchu byly v módě do třicátých let minulého století, než slavní šampióni jako Giuseppe Campari, Rudolf Caracciola, Louis Chiron, Tazio je začaly postupně nahrazovat závody na okruzích. Některé však Nuvolari, Hans Stuck a Achille Varzi. Na přetrvaly do současnosti a některé se dočkaly vzkříšení. Závody do startu v Linthalu se objevili i Herman Lang sedla Klausen byly vždy výjimečné, ať svou délkou a převýšením a Bernd Rosemeyer, i když to tehdy byli nebo účastí strojů a jezdců. Když nám Jiří W. Pollak pomohl vyří- teprve začátečníci startující na motocy- dit účast sidecaru Rudge posádky Jiří Hlavsa–Jiří Snop v barvách klech. -

Contents Welcome to the World of Racing Orld of Racing

NO. 383 FEBRUARY 2014 Contents Welcome To The World Of Racing Events...................................2 uring this month, I have managed to find a bit of spare time Diary Dates..........................6 Don a Monday evening and after numerous promises to fellow Messages From Margate......7 NSCC member, Chris Gregory I managed to pop along to his local Ninco News........................13 club, Croydon Scalextric Club to give this racing thing a try. Forza Slot.it........................15 Well after my third visit I can say what a great way to spend an Carrera Corner..................19 evening and also a bit of cash! Having been in the winning team at Bits and Pieces....................21 Ramsgate for two years in a row (and no it was a not a fix Mark!) I Chopper’s Woodyard.........23 thought perhaps I could stand shoulder to shoulder in this keen and Swindon Swapmeet...........29 competitive environment.... well actually no I can’t I have so far been Racer Report.....................36 comprehensively beaten virtually every race, coming fourth out of Micro Scalextric History....38 four, although last week I did somehow manage to win a race using Ebay Watch........................41 the club cars? Members Adverts...............44 Peter Simpson, who is also one of the members will be writing Dear NSCC.......................45 a piece soon on the Croydon Club, but in the meantime can I suggest if you have never tried club racing give it a go, if the members are anything like the Croydon mob, it will be a lot of fun and you’ll be made