Orthographic Encoding of the Viennese Dialect for Machine Translation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Suchoff Family Resemblances: Ludwig Wittgenstein As a Jewish Philosopher the Admonition to Silence with Which Wittgenstein

David Suchoff Family Resemblances: Ludwig Wittgenstein as a Jewish Philosopher The admonition to silence with which Wittgenstein ended the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922) also marks the starting point for the emer- gence of his Jewish philosophical voice. Karl Kraus provides an instructive contrast: as a writer well known to Wittgenstein, Kraus’s outspoken and aggressive ridicule of “jüdeln” or “mauscheln” –the actual or alleged pronunciation of German with a Jewish or Yiddish accent – defined a “self-fashioning” of Jewish identity – from German and Hebrew in this case – that modeled false alternatives in philosophic terms.1 Kraus pre- sented Wittgenstein with an either-or choice between German and Jewish identity, while engaging in a witty but also unwitting illumination of the interplay between apparently exclusive alternatives that were linguistically influenced by the other’s voice. As Kraus became a touchstone for Ger- man Jewish writers from Franz Kafka to Walter Benjamin and Gershom Scholem, he also shed light on the situation that allowed Wittgenstein to develop his own non-essentialist notion of identity, as the term “family resemblance” emerged from his revaluation of the discourse around Judaism. This transition from The False Prison, as David Pears calls Wittgenstein’s move from the Tractatus to the Philosophical Investiga- tions, was also a transformation of the opposition between German and Jewish “identities,” and a recovery of the multiple differences from which such apparently stable entities continually draw in their interconnected forms of life.2 “I’ll teach you differences,” the line from King Lear that Wittgenstein mentioned to M. O’C. Drury as “not bad” as a “motto” for the Philo- sophical Investigations, in this way represents Wittgenstein’s assertion of a German Jewish philosophic position. -

Fertility and Modernity*

Fertility and Modernity Enrico Spolaore Romain Wacziarg Tufts University and NBER UCLA and NBER May 2021 Abstract We investigate the determinants of the fertility decline in Europe from 1830 to 1970 using a newly constructed dataset of linguistic distances between European regions. We …nd that the fertility decline resulted from a gradual di¤usion of new fertility behavior from French-speaking regions to the rest of Europe. We observe that societies with higher education, lower infant mortality, higher urbanization, and higher population density had lower levels of fertility during the 19th and early 20th century. However, the fertility decline took place earlier and was initially larger in communities that were culturally closer to the French, while the fertility transition spread only later to societies that were more distant from the cultural frontier. This is consistent with a process of social in‡uence, whereby societies that were linguistically and culturally closer to the French faced lower barriers to learning new information and adopting new behavior and attitudes regarding fertility control. Spolaore: Department of Economics, Tufts University, Medford, MA 02155-6722, [email protected]. Wacziarg: UCLA Anderson School of Management, 110 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles CA 90095, [email protected]. We thank Quamrul Ashraf, Guillaume Blanc, John Brown, Matteo Cervellati, David De La Croix, Gilles Duranton, Alan Fernihough, Raphael Franck, Oded Galor, Raphael Godefroy, Michael Huberman, Yannis Ioannides, Noel Johnson, David Le Bris, Monica Martinez-Bravo, Jacques Melitz, Deborah Menegotto, Omer Moav, Luigi Pascali, Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, Nico Voigtländer, Joachim Voth, Susan Watkins, David Yanagizawa-Drott as well as participants at numerous seminars and conferences for useful comments. -

Unsupervised and Phonologically Controlled Interpolation of Austrian German Language Varieties for Speech Synthesis

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Speech Communication 72 (2015) 176–193 www.elsevier.com/locate/specom Unsupervised and phonologically controlled interpolation of Austrian German language varieties for speech synthesis Markus Toman a,⇑, Michael Pucher a, Sylvia Moosmu¨ller b, Dietmar Schabus a a Telecommunications Research Center Vienna (FTW), Donau-City-Str 1, 3rd floor, 1220 Vienna, Austria b Austrian Academy of Sciences – Acoustics Research Institute (ARI), Wohllebengasse 12-14, 1st Floor, 1040 Vienna, Austria Received 10 December 2014; received in revised form 18 May 2015; accepted 4 June 2015 Available online 12 June 2015 Abstract This paper presents an unsupervised method that allows for gradual interpolation between language varieties in statistical parametric speech synthesis using Hidden Semi-Markov Models (HSMMs). We apply dynamic time warping using Kullback–Leibler divergence on two sequences of HSMM states to find adequate interpolation partners. The method operates on state sequences with explicit durations and also on expanded state sequences where each state corresponds to one feature frame. In an intelligibility and dialect rating subjective evaluation of synthesized test sentences, we show that our method can generate intermediate varieties for three Austrian dialects (Viennese, Innervillgraten, Bad Goisern). We also provide an extensive phonetic analysis of the interpolated samples. The analysis includes input-switch rules, which cover historically different phonological developments of the dialects versus the standard language; and phonological processes, which are phonetically motivated, gradual, and common to all varieties. We present an extended method which linearly interpolates phonological processes but uses a step function for input-switch rules. Our evaluation shows that the integra- tion of this kind of phonological knowledge improves dialect authenticity judgment of the synthesized speech, as performed by dialect speakers. -

'Sich Ausgehen': on Modalizing Go Constructions in Austrian German

‘Sich ausgehen’: On modalizing go constructions in Austrian German Remus Gergel, Martin Kopf-Giammanco Saarland University, prefinal draft, July 2020; to appear in Canadian Journal of Linguistics∗ Abstract The goal of this paper is to diagnose a verbal construction based on the verb gehen (‘go’) conjoined by a particle and the reflexive, which has made it to common use in Austrian German and is typically unknown to many speakers of Federal German who have not been exposed to Austrian German. An argument for a degree-based sufficiency construction is developed, the analysis of which is constructed by extending existing approaches in the literature on enough constructions and suggesting a meaning of the specific construction at hand which is presuppositional in multiple respects. The results of diachronic corpus searches as well as the significance of the results in the space of possibilities for the semantic change of motion verbs are discussed. Keywords: ‘go’ constructions, sufficiency, modality 1 Introduction The goal of this paper is to diagnose a construction based on the verb gehen (‘go’), a particle, and the reflexive, which has made it to common use in Austrian German: (1) Context: Stefan has an appointment in half an hour. Before that, he would like to have a cup of coffee and a quick chat with Paul. This could be a bit tight, but then he thinks: Ein Kaffee mit Paul geht sich vor dem Termin aus. a coffee with Paul goes itself before the appointment out ‘I can have a (cup of) coffee with Paul before the appointment.’/’There is enough time for a coffee with Paul before the appointment. -

Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Flagging in English-Italian Code-Switching Rosignoli, Alberto

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Flagging in English-Italian code-switching Rosignoli, Alberto Award date: 2011 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 FLAGGING IN ENGLISH- ITALIAN CODE-SWITCHING Alberto Rosignoli Ysgol Ieithyddiaeth ac Iaith Saesneg - School of Linguistics & English Language Prifysgol Bangor University PhD 2011 Summary his thesis investigates the phenomenon of flagging in code-switching. The T term ‘flagging’ is normally used to describe a series of discourse phenomena occurring in the environment of a switch. In spite of a large literature on code- switching, not much is known about flagging, aside from the general assumption that it has signalling value and may draw attention to the switch (Poplack, 1988). The present study aims to offer a more eclectic understanding of flagging, by looking at the phenomenon from both a structural and an interpretive perspective. -

Wittgenstein's Vienna Our Aim Is, by Academic Standards, a Radical One : to Use Each of Our Four Topics As a Mirror in Which to Reflect and to Study All the Others

TOUCHSTONE Gustav Klimt, from Ver Sacrum Wittgenstein' s VIENNA Allan Janik and Stephen Toulmin TOUCHSTONE A Touchstone Book Published by Simon and Schuster Copyright ® 1973 by Allan Janik and Stephen Toulmin All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form A Touchstone Book Published by Simon and Schuster A Division of Gulf & Western Corporation Simon & Schuster Building Rockefeller Center 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10020 TOUCHSTONE and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster ISBN o-671-2136()-1 ISBN o-671-21725-9Pbk. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 72-83932 Designed by Eve Metz Manufactured in the United States of America 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 The publishers wish to thank the following for permission to repro duce photographs: Bettmann Archives, Art Forum, du magazine, and the National Library of Austria. For permission to reproduce a portion of Arnold SchOnberg's Verklarte Nacht, our thanks to As sociated Music Publishers, Inc., New York, N.Y., copyright by Bel mont Music, Los Angeles, California. Contents PREFACE 9 1. Introduction: PROBLEMS AND METHODS 13 2. Habsburg Vienna: CITY OF PARADOXES 33 The Ambiguity of Viennese Life The Habsburg Hausmacht: Francis I The Cilli Affair Francis Joseph The Character of the Viennese Bourgeoisie The Home and Family Life-The Role of the Press The Position of Women-The Failure of Liberalism The Conditions of Working-Class Life : The Housing Problem Viktor Adler and Austrian Social Democracy Karl Lueger and the Christian Social Party Georg von Schonerer and the German Nationalist Party Theodor Herzl and Zionism The Redl Affair Arthur Schnitzler's Literary Diagnosis of the Viennese Malaise Suicide inVienna 3. -

Word Order in German-English Mixed Discourse*

Word order in German-English mixed discourse* EVA EPPLER Abstract Intrasententially code-switched data pose an interesting problem for syntactic research as two grammars interact in one utterance. Constituent-based models have been shown to have difficulties accounting for mixing between SVO and SOV languages like English and German. In an analysis of code-switched and monolingual subordinate clauses, I show that code-mixing patterns can be studied productively in terms of a dependency analysis which recognises words but not phrases. That is, each word in a switched dependency satisfies the constraints imposed on it by its own language. Quantitative methodologies, in addition to the dependency analysis, are essential because some of the influences of code- switching are probabilistic rather than absolute. 1 Introduction If German-English bilinguals want to code-switch subordinate clauses, they need to resolve the problem of English being SVO and German finite verbs depending on lexical complementizers generally being placed in clause-final position1. How this word order contrast is resolved is relevant to the question underlying all grammatical code- switching research, i.e. whether there are syntactic constraints on code-mixing. The first section will discuss the theoretical background to this controversy, followed by a description of the corpus and the theoretical assumptions this particular study is based on. The third section states the relevant word order rules for finite verbs in German and English, and the main sections present the data and the structural analyses. The analyses will highlight the importance of a quantitative analysis, and will show that * I would like to thank Dick Hudson, Mark Sebba and Jeanine Treffers-Daller for their comments, Randall Jones for his data and David for making me laugh. -

The Grammar of Words

www.IELTS4U.blogfa.com Series editors Keith Brown, Eve V. Clark, April McMahon, Jim Miller, and Lesley Milroy The Grammar of Words www.IELTS4U.blogfa.com O XFORD T EXTBOOKS IN L INGUISTICS General editors: Keith Brown, University of Cambridge; Eve V. Clark, Stanford University; April McMahon, University of Sheffield; Jim Miller, University of Auckland; Lesley Milroy, University of Michigan This series provides lively and authoritative introductions to the approaches, methods, and theories associated with the main subfields of linguistics. P The Grammar of Words An Introduction to Linguistic Morphology by Geert Booij A Practical Introduction to Phonetics Second edition by J. C. Catford Meaning in Language An Introduction to Semantics and Pragmatics Second edition by Alan Cruse www.IELTS4U.blogfa.comPrinciples and Parameters An Introduction to Syntactic Theory by Peter W. Culicover Semantic Analysis A Practical Introduction by Cliff Goddard Cognitive Grammar An Introduction by John R. Taylor Linguistic Categorization Third edition by John R. Taylor I Pragmatics by Yan Huang The Grammar of Words An Introduction to Linguistic Morphology Geert Booij www.IELTS4U.blogfa.com 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan South Korea Poland Portugal Singapore Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc. -

![Ach, Ich Und Die /R/-Vokalisierung.” on the Difference in the Distribution of [X] and [Ç] in Standard German and Standard Austrian German](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1597/ach-ich-und-die-r-vokalisierung-on-the-difference-in-the-distribution-of-x-and-%C3%A7-in-standard-german-and-standard-austrian-german-3041597.webp)

Ach, Ich Und Die /R/-Vokalisierung.” on the Difference in the Distribution of [X] and [Ç] in Standard German and Standard Austrian German

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit “Ach, ich und die /r/-Vokalisierung.” On the difference in the distribution of [x] and [ç] in Standard German and Standard Austrian German. Verfasserin Tina Hildenbrandt angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 328 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Allgem./Angew. Sprachwissenschaft Betreuer: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. John Rennison Acknowledgments I want to thank ... John Rennison for the supervision, the tech support, the native speaker competence, and for introducing me to the exiting world of GP and, of course, Government Phonology Round Tables. Sylvia Moosmüller for all the help, encouragement and general everything, as well as showing me that phonetics is fun. Friedrich Neubarth for all the input, the brutal, helpful feedback and the joy of discussing more or less megalomaniac ideas. Hans Christian Luschützky for pointing out the topic to me in the first place. the staff of the Acoustics Research Institute of the Austrian Academy of Sciences for letting me be a part of it and giving me the opportunity to bemuse them with generative phonology as well as, of course, the corpus, the Foosball and the DnD. Julia Brandstätter for patiently answering questions like “How do I see the prepalatal constriction location in the F2 here again?”. my peers at the University of Vienna for “Illegal Tutorials” first (Thank you Markus Pöchtrager), the Mafiosi get-togethers later and, in particular, David Djabbari for these very helpful phonology-billiard-meetings. my teachers and colleagues at the EGG schools, the Central European Summer Schools for Generative Grammar, in the years 2010, 2011 and 2012. -

THE CHANGE of DIPHTHONGS in STANDARD VIENNESE GERMAN: the DIPHTHONG /Ae

THE CHANGE OF DIPHTHONGS IN STANDARD VIENNESE GERMAN: THE DIPHTHONG /aE/ Ralf Vollmann* and Sylvia Moosmüller† *Institute of Linguistics, University of Graz, Austria, †Acoustics Research Department, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna, Austria ABSTRACT since the dialect lacked lax vowels anyway. The opposition of Standard long tense and short lax vowels is expressed by long The realization of the diphthongs /aE/ and /A/ of Standard versus short tense vowels in the dialect system. In the Viennese Austrian German differs between the two big dialect regions and dialect, therefore, the process of monophthongization has to be this difference also affects the process of monophthongization, described as a prelexical process [2]. especially affecting the direction of the assimilation. However, Probably as a result of the Viennese Dialect, the process of neither the difference in diphthong realization nor the difference monophthongization affected the Viennese Standard as well, in the application of the process of monophthongization existed in though postlexically. That means, the process is applied as a the late nineteen-fifties. Observing the realization of the diphthong function of well-known linguistic and socio-psychological /aE/ over the past decades, a constant rise of F2 can be observed at variables [8, 9, 12]. The relation between the Viennese Dialect and the Viennese Standard as concerns the process of monoph- the onset of the diphthog in the Viennese Standard variety. thongization can be described as follows: Gradually, in the Viennese Standard variety, the onset steady state of the diphthong /aE/ has given way to a gliding movement. Long offset steady state portions could be observed in the late seventies for the first time, consequently, they have to be interpreted as uncertainty in diphthong articulation due to the rapid progession of the process of monophthongization. -

7.8 Post-Yiddish Ashkenazic Speech This Spurred Conscious and Serious Attempts at Orthographic Reform (Schaechter 303 1999: 4)

302 Sociolinguistics 7.8 Post-Yiddish Ashkenazic speech This spurred conscious and serious attempts at orthographic reform (Schaechter 303 1999: 4). The major breakthrough came in the lexicographic work of Lifshits their own (such as the newspaper Der Forverts, founded 1897) have recently switched to StY orthography. (1867, 1869, 1876). The impact of Lifshits was significant in setting the di rection of future orthographic reform. Among Lifshits' specific innovations. Schaechter (1999: 4) cites: the roje diacritic on IfI !l to distinguish it from Ip/e; 7.7.5 Romanization systems syllabic" I (vs. daytshmerish ~S) -ell, e.g., "O'il himl 'sky'; svarabhakti vowel, e.g.,I!l'JS)rt1s)i~:::l badeif-;}-nis 'need' (cf. StG 8ediirf-~-nis); suffixes lS), 1S)~ (vs. The orthography debates also included calls for romanization _ the writing daytshmerish spelling,., T~; cf. StG -ich, -lich); dropping ofsilent S) in, e.g., lib, of Yiddish in Latin letters (for internal use within the Yiddish speech commu fil (vs. daytshmerish :::ls)'~, ~S)'~ cf. StG Lieb, vie/); use of' to indicate palatal nity). Serious early calls for romanization came from prominent figures: Nathan ized consonants s)i~'" /I' ad,,1 'any,' Ql)i~'" /I'arnml 'noise'; word-final t:l (tes) Birnbaum (in his early years), the convener of the 1908 TShernovits conference; replacing daytshmerish it thus: t:l~il 'hand; arm,' t:lJ'" 'wind,' t:l~s)J 'money' (cf. Ludwig Zamenhof; Zaretski; Zhitlovski; Yofe; and others (Schaechter 1999: StG Hand, Wind, Geld). 16). The earliest such voice was likely Dr. Philip Mansch (1888-1890). Over In general, the history of StY orthography involves an ongoing process to whelmingly, however, there was a strong negative reaction to romanization, free itself from daytshmerish orthography. -

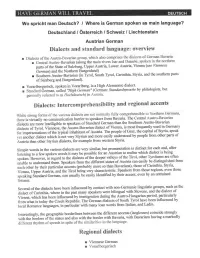

Dialects and Standard Language

HA VE GERMAN WILL TRAVEL DEUTSCH Wo spricht man Deutsch? I Where is German spoken as main language? Deutschland I Osterreich / Schweiz I Liechtenstein Austrian German Dialects and standard language: overview ■ Dialects of the Austro-Bavarian group, which also comprises the dialects of German Bavaria ■ Central Austro-Bavarian (along the main rivers Isar and Danube, spoken in the northern parts of the State of Salzburg, Upper Austria, Lower Austria, Vienna (see Viennese German) and the Northern Burgenland) ■ Southern Austro-Bavarian (in Tyrol, South Tyrol, Carinthia, Styria, and the southern parts of Salzburg and Burgenland). ■ Vorarlbergerisch, spoken in Vorarlberg, is a High A1emannic dialect. ■ Standard German, called "High German" (German: Standardsprache by philologists, but generally referred to as Hochdeutsch) in Austria. Dialects: lntercomprehensibility and regional accents While strong forms of the various dialects are not normally fully comprehensible to Northern Germans, there is virtually no communication barrier to speakers from Bavaria. The Central Austro-Bavarian dialects are more intelligible to speakers of Standard German than the Southern Austro-Bavarian dialects of Tyrol. Viennese, the Austro-Bavarian dialect of Vienna, is most frequently used in Germany for impersonations of the typical inhabitant of Austria. The people of Graz, the capital of Styria, speak yet another dialect which is not very Styrian and more easily understood by people from other parts of Austria than other Styrian dialects, for example from western Styria. Simple words in the various dialects are very similar, but pronunciation is distinct for each and, after listening to a few spoken words it may be possible for an Austrian to realise which dialect is being spoken.