The Role of Passive Migration in the Dispersal of Resistance Genes in Culex Pipiens Quinquefasciatus Within French Polynesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

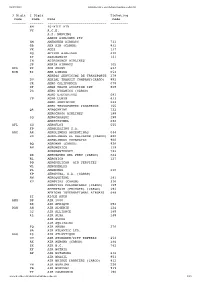

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

Hilton Hotel Tahiti PO Box 416 98713 Papeete - Tahiti - French Polynesia Tel: +689 86 48 48 Fax: +689 86 48 00 Email : [email protected] Hilton.Com

Hilton Hotel Tahiti PO box 416 98713 Papeete - Tahiti - French Polynesia Tel: +689 86 48 48 Fax: +689 86 48 00 Email : [email protected] hilton.com Location The island of Tahiti is brimming with not-to-be-missed visual and cultural riches and the resort is an ideal jumping off point for adventure….explore sacred sites, relive history, The hotel is situated on the main island scuba dive over old shipwrecks, sail, surf or enjoy a sunset cruise. of Tahiti, a few minutes from downtown Papeete and 5 minutes from Tahiti Faa’a The Hilton Hotel Tahiti offers a warm welcome to international travellers, immediately International Airport. connecting them to the rich cultural traditions of Tahiti and her islands. The hotel - built on the very land where Princess Pomare made her home a century Flight times from main cities: before – opened in 1960 as the first Tahitian hotel whose design was inspired by Los Angeles: daily (8h); Polynesian culture. The hotel is the soul of the island, providing eloquent connections Paris: daily (20h); between Polynesian history, modern-day island culture and international influences. Tokyo: weekly (12h); The beloved Hilton Hotel Tahiti is a completely renovated retreat still rooted in its historic Santiago (Chile): weekly (10h); island charm. Auckland: weekly (6h) The hotel offers 178 spacious and modern rooms, 10 suites and 4 apartments, facing the lagoon or the island of Moorea. Local inter-island travel: • Air Moorea: regular 7-minute flight shuttle to neighboring island of Moorea Special Features • Air Tahiti: inter island services to all • The hotel has an ideal location, a few minutes from downtown Papeete with its shops and 5 archipelagos – including to Bora Bora fascinating local market and just 5 minutes from Tahiti Faa’a International Airport. -

Annual Report 2007

EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 1 Analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 EUROPEAN COMMISSION EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 2 Air Transport and Airport Research Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 German Aerospace Center Deutsches Zentrum German Aerospace für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V. Center in the Helmholtz-Association Air Transport and Airport Research December 2008 Linder Hoehe 51147 Cologne Germany Head: Prof. Dr. Johannes Reichmuth Authors: Erik Grunewald, Amir Ayazkhani, Dr. Peter Berster, Gregor Bischoff, Prof. Dr. Hansjochen Ehmer, Dr. Marc Gelhausen, Wolfgang Grimme, Michael Hepting, Hermann Keimel, Petra Kokus, Dr. Peter Meincke, Holger Pabst, Dr. Janina Scheelhaase web: http://www.dlr.de/fw Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02 Release: 2.2 Page 1 Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 Document Control Information Responsible project manager: DG Energy and Transport Project task: Annual analyses of the European air transport market 2007 EC contract number: TREN/05/MD/S07.74176 Release: 2.2 Save date: 2008-12-02 Total pages: 222 Change Log Release Date Changed Pages or Chapters Comments 1.2 2008-06-20 Final Report 2.0 2008-10-10 chapters 1,2,3 Final Report - full year 2007 draft 2.1 2008-11-20 chapters 1,2,3,5 Final updated Report 2.2 2008-12-02 all Layout items Disclaimer and copyright: This report has been carried out for the Directorate-General for Energy and Transport in the European Commission and expresses the opinion of the organisation undertaking the contract TREN/05/MD/S07.74176. -

Document.Pdf

SOMMAIRE / SUMMARY N°60 SEPTEMBRE - OCTOBRE - nOVEMBRE / SEPTEMBER - OCTOBER - NOVEMBER 2008 8 NEWS AIR TAHITI AIR TAHITI MAGAZINE est une publication de SARL TAHITI COMMUNICATION 157 rue du Régent Paraita 98713 Papeete - Tahiti 12 DESTINATION Polynésie française • Tél. (689) 83 14 83 • Fax. (689) 83 16 83 Fakarava • Mail. [email protected] Le domaine des Océans Régie publicitaire : Tahiticommunication SARL au capital de 1 000 000 Fcfp Fakarava, An oceanic domain RCS. 05 336 B N°Tahiti. 758 268 Code NAF. 744B Directeur de la publication Director of the publication Marc Ramel naTURE 28 Directeur de production Director of productor Enzo Rizzo Tiare Maohi, Tiare Tahiti Ce don des dieux REGIE PUBLICITAIRE tiare maohi, Tiare Tahiti ADVERTISING Enzo Rizzo • Tél. (689) 746 946 A gift from the gods Rédacteur en chef / Chief editor Ludovic Lardière RÉDACTION / TEXT Julien Gué 44 CULTURE Conception Graphique GraphiC design Yannick Peyronnet Tatau,Tatouage Polynésien, PHOTO DE COUVERTURE / COVER LA renaissance Hélène Barnaud Tatau, Polynesian tatoos Adaptation anglaise the renaissance English translation Celeste Brash Secrétariat et administration Secretariat and administration Marisa Moux Impression / Printed in 62 STP Multipress Dépot légal à parution. Tirage : 18 000 exemplaires ZOOM SUR AIR TAHITI www.airtahiti.aero FOCUS ON AIR TAHITI Revue de bord N°60 / AIR TAHITI / On-board Magazine N°60 3 édITORIAL / EdITORIAL ia ora na et maeva ia ora na and Maeva (Welcome) ! Bienvenue à bord de ce nouveau numéro d’Air Tahiti Magazine. Welcome aboard the latest edition of Air Tahiti Magazine. in this Nous vous proposons de mettre le cap sur l’archipel des Tuamotu edition we invite you to explore the Tuamotu Archipelago and, et plus précisément une de ses îles, Fakarava. -

Airlines Prefix Codes 1

AMERICAN AIRLINES,INC (AMERICAN EAGLE) UNITED STATES 001 0028 AA AAL CONTINENTAL AIRLINES (CONTINENTAL EXPRESS) UNITED STATES 005 0115 CO COA DELTA AIRLINES (DELTA CONNECTION) UNITED STATES 006 0128 DL DAL NORTHWEST AIRLINES, INC. (NORTHWEST AIRLINK) UNITED STATES 012 0266 NW NWA AIR CANADA CANADA 014 5100 AC ACA TRANS WORLD AIRLINES INC. (TRANS WORLD EXPRESS) UNITED STATES 015 0400 TW TWA UNITED AIR LINES,INC (UNITED EXPRESS) UNITED STATES 016 0428 UA UAL CANADIAN AIRLINES INTERNATIONAL LTD. CANADA 018 2405 CP CDN LUFTHANSA CARGO AG GERMANY 020 7063 LH GEC FEDERAL EXPRESS (FEDEX) UNITED STATES 023 0151 FX FDX ALASKA AIRLINES, INC. UNITED STATES 027 0058 AS ASA MILLON AIR UNITED STATES 034 0555 OX OXO US AIRWAYS INC. UNITED STATES 037 5532 US USA VARIG S.A. BRAZIL 042 4758 RG VRG HONG KONG DRAGON AIRLINES LIMITED HONG KONG 043 7073 KA HDA AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS ARGENTINA 044 1058 AR ARG LAN-LINEA AEREA NACIONAL-CHILE S.A. CHILE 045 3708 LA LAN TAP AIR PORTUGAL PORTUGAL 047 5324 TP TAP CYPRUS AIRWAYS, LTD. CYPRUS 048 5381 CY CYP OLYMPIC AIRWAYS GREECE 050 4274 OA OAL LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO S.A. BOLIVIA 051 4054 LB LLB AER LINGUS LIMITED P.L.C. IRELAND 053 1254 EI EIN ALITALIA LINEE AEREE ITALIANE ITALY 055 1854 AZ AZA CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES LTD. CO. CYPRUS 056 5999 YVK AIR FRANCE FRANCE 057 2607 AF AFR INDIAN AIRLINES INDIA 058 7009 IC IAC AIR SEYCHELLES UNITED KINGDOM 061 7059 HM SEY AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL NEW CALEDONIA 063 4465 SB ACI CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES CZECHOSLAVAKIA 064 2432 OK CSA SAUDI ARABIAN AIRLINES SAUDI ARABIA 065 4650 SV SVA AIR MOOREA FRENCH POLYNESIA 067 4832 QE TAH LAM-LINHAS AEREAS DE MOCAMBIQUE MOZAMBIQUE 068 7119 TM LAM SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES SYRIA 070 7127 RB SYR ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES ENTERPRISE ETHIOPIA 071 3224 ET ETH GULF AIR COMPANY G.S.C. -

Proceedings 2008.Pmd

VOLUME 12 Publisher ISASI (Frank Del Gandio, President) Editorial Advisor Air Safety Through Investigation Richard B. Stone Editorial Staff Susan Fager Esperison Martinez Design William A. Ford Proceedings of the ISASI Proceedings (ISSN 1562-8914) is published annually by the International Society of Air Safety Investigators. Opin- 39th Annual ISASI 2008 PROCEEDINGS ions expressed by authors are not neces- sarily endorsed or represent official ISASI position or policy. International Seminar Editorial Offices: 107 E. Holly Ave., Suite 11, Sterling, VA 20164-5405 USA. Tele- phone: (703) 430-9668. Fax: (703) 450- 1745. E-mail address: [email protected]. Internet website: http://www.isasi.org. ‘Investigation: The Art and the Notice: The Proceedings of the ISASI 39th annual international seminar held in Science’ Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, features presentations on safety issues of interest to the aviation community. The papers are presented herein in the original editorial Sept. 8–11, 2008 content supplied by the authors. Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada Copyright © 2009—International Soci- ety of Air Safety Investigators, all rights reserved. Publication in any form is pro- hibited without permission. Permission to reprint is available upon application to the editorial offices. Publisher’s Editorial Profile: ISASI Pro- ceedings is printed in the United States and published for professional air safety inves- tigators who are members of the Interna- tional Society of Air Safety Investigators. Content emphasizes accident investigation findings, investigative techniques and ex- periences, and industry accident-preven- tion developments in concert with the seminar theme “Investigation: The Art and the Science.” Subscriptions: Active members in good standing and corporate members may ac- quire, on a no-fee basis, a copy of these Proceedings by downloading the material from the appropriate section of the ISASI website at www.isasi.org. -

Bulletin De Statistiques Commerciales 2000

MINISTERE DE L’EQUIPEMENT, DES TRANSPORTS ET DU LOGEMENT DIRECTION GENERALE DE L’AVIATION CIVILE DIRECTION DES TRANSPORTS AERIENS SOUS-DIRECTION DES ETUDES ECONOMIQUES ET DE LA PROSPECTIVE BUREAU DE L’OBSERVATION ECONOMIQUE P1 BULLETIN STATISTIQUE TRAFIC COMMERCIAL ANNEE 2000 AVRIL 2001 50, RUE HENRI FARMAN 75720 PARIS CEDEX 15 - TEL : 01 58 09 49 81 - FAX : 01 58 09 48 83 Le Bulletin Statistique de la Direction Générale de l'Aviation Civile est élaboré à partir des statistiques de trafic commercial provenant de l'ensemble des plates-formes françaises. Il regroupe un ensemble de statistiques essentielles pour la connaissance du transport aérien en France. L'édition de ce bulletin repose sur la fourniture par chacun des aéroports français de ses propres données. Ces données sont harmonisées, puis analysées suivant l’origine- destination du vol par numéro de vol. Des corrections nécessaires sont ensuite apportées en concertation avec les services aéroportuaires et/ou les Directions de l’Aviation Civile qui communiquent les résultats de trafic. La date de parution de ce bulletin dépend donc des délais de transmission des données par l’ensemble des fournisseurs de statistiques. Ce bulletin comprend cinq chapitres : -- le premier est une synthèse des résultats de l’année civile, -- le deuxième regroupe le trafic des compagnies françaises, tel qu’il ressort des informations communiquées à la Direction Générale de l’Aviation Civile, -- le troisième est consacré aux trafics des relations entre la France et les pays étrangers, -- les deux derniers regroupent le trafic des relations de la Métropole ou de l’Outre Mer avec les pays étrangers ainsi que le trafic des aéroports de ces deux espaces. -

List of Government-Owned and Privatized Airlines (Unofficial Preliminary Compilation)

List of Government-owned and Privatized Airlines (unofficial preliminary compilation) Governmental Governmental Governmental Total Governmental Ceased shares shares shares Area Country/Region Airline governmental Governmental shareholders Formed shares operations decreased decreased increased shares decreased (=0) (below 50%) (=/above 50%) or added AF Angola Angola Air Charter 100.00% 100% TAAG Angola Airlines 1987 AF Angola Sonair 100.00% 100% Sonangol State Corporation 1998 AF Angola TAAG Angola Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1938 AF Botswana Air Botswana 100.00% 100% Government 1969 AF Burkina Faso Air Burkina 10.00% 10% Government 1967 2001 AF Burundi Air Burundi 100.00% 100% Government 1971 AF Cameroon Cameroon Airlines 96.43% 96.4% Government 1971 AF Cape Verde TACV Cabo Verde 100.00% 100% Government 1958 AF Chad Air Tchad 98.00% 98% Government 1966 2002 AF Chad Toumai Air Tchad 25.00% 25% Government 2004 AF Comoros Air Comores 100.00% 100% Government 1975 1998 AF Comoros Air Comores International 60.00% 60% Government 2004 AF Congo Lina Congo 66.00% 66% Government 1965 1999 AF Congo, Democratic Republic Air Zaire 80.00% 80% Government 1961 1995 AF Cofôte d'Ivoire Air Afrique 70.40% 70.4% 11 States (Cote d'Ivoire, Togo, Benin, Mali, Niger, 1961 2002 1994 Mauritania, Senegal, Central African Republic, Burkino Faso, Chad and Congo) AF Côte d'Ivoire Air Ivoire 23.60% 23.6% Government 1960 2001 2000 AF Djibouti Air Djibouti 62.50% 62.5% Government 1971 1991 AF Eritrea Eritrean Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1991 AF Ethiopia Ethiopian -

3 Digit 2 Digit Ticketing Code Code Name Code ------6M 40-MILE AIR VY A.C.E

06/07/2021 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt 3 Digit 2 Digit Ticketing Code Code Name Code ------- ------- ------------------------------ --------- 6M 40-MILE AIR VY A.C.E. A.S. NORVING AARON AIRLINES PTY SM ABERDEEN AIRWAYS 731 GB ABX AIR (CARGO) 832 VX ACES 137 XQ ACTION AIRLINES 410 ZY ADALBANAIR 121 IN ADIRONDACK AIRLINES JP ADRIA AIRWAYS 165 REA RE AER ARANN 684 EIN EI AER LINGUS 053 AEREOS SERVICIOS DE TRANSPORTE 278 DU AERIAL TRANSIT COMPANY(CARGO) 892 JR AERO CALIFORNIA 078 DF AERO COACH AVIATION INT 868 2G AERO DYNAMICS (CARGO) AERO EJECUTIVOS 681 YP AERO LLOYD 633 AERO SERVICIOS 243 AERO TRANSPORTES PANAMENOS 155 QA AEROCARIBE 723 AEROCHAGO AIRLINES 198 3Q AEROCHASQUI 298 AEROCOZUMEL 686 AFL SU AEROFLOT 555 FP AEROLEASING S.A. ARG AR AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 044 VG AEROLINEAS EL SALVADOR (CARGO) 680 AEROLINEAS URUGUAYAS 966 BQ AEROMAR (CARGO) 926 AM AEROMEXICO 139 AEROMONTERREY 722 XX AERONAVES DEL PERU (CARGO) 624 RL AERONICA 127 PO AEROPELICAN AIR SERVICES WL AEROPERLAS PL AEROPERU 210 6P AEROPUMA, S.A. (CARGO) AW AEROQUETZAL 291 XU AEROVIAS (CARGO) 316 AEROVIAS COLOMBIANAS (CARGO) 158 AFFRETAIR (PRIVATE) (CARGO) 292 AFRICAN INTERNATIONAL AIRWAYS 648 ZI AIGLE AZUR AMM DP AIR 2000 RK AIR AFRIQUE 092 DAH AH AIR ALGERIE 124 3J AIR ALLIANCE 188 4L AIR ALMA 248 AIR ALPHA AIR AQUITAINE FQ AIR ARUBA 276 9A AIR ATLANTIC LTD. AAG ES AIR ATLANTIQUE OU AIR ATONABEE/CITY EXPRESS 253 AX AIR AURORA (CARGO) 386 ZX AIR B.C. 742 KF AIR BOTNIA BP AIR BOTSWANA 636 AIR BRASIL 853 AIR BRIDGE CARRIERS (CARGO) 912 VH AIR BURKINA 226 PB AIR BURUNDI 919 TY AIR CALEDONIE 190 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt 1/15 06/07/2021 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt SB AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 063 ACA AC AIR CANADA 014 XC AIR CARIBBEAN 918 SF AIR CHARTER AIR CHARTER (CHARTER) AIR CHARTER SYSTEMS 272 CCA CA AIR CHINA 999 CE AIR CITY S.A. -

Copyrighted Material

Avea Bay (Baie Avea; Huahine), Bora Bora Lagoonarium, 189, 190 Index 156, 160 Bora Bora Parasail, 190 Avea Beach (Huahine), 162 Bora Pearl Company, 191 GENERAL INDEX See also Accommodations and Botanical Gardens, Harrison W. Restaurant indexes, below. Smith (Tahiti), 105 B Botanical Gardens (Papeete), 95 Baggage allowances, 47 Bougainville, Antoine de, 15 Baggage storage, 50 Bougainville’s Anchorage General Index Baie Avea (Avea Bay; Huahine), (Tahiti), 102 A 156 Bounty, HMS, 19–21 Baie des Vierges (FatuHiva), 264 Boutique Bora Bora, 191 Abercrombie & Kent, 66 Bain Loti (Loti’s Pool; Tahiti), 100 Boutique d’Art Marquisien Accommodations, 73–75. See Bali Hai Boys (Moorea), 144 (Moorea), 140 also specific destinations; and Banks. See Currency and Boutique Gauguin (Bora Bora), Accommodations Index currency exchange 191 best, 3–7 Banque de Polynésie, 50 Brando, Marlon, 108 Active vacations, 68–70 Banque Socredo, 50 Briac, Olivier, 137 Adventure Eagle Tours, 109 Bathy’s Dive Center (Tahiti), Bugs, 59 Aehautai Marae (Bora Bora), 187 110, 111 Buses, 52 Afareaitu (Moorea), 135 Bathy’s Diving (Moorea), 139 Business hours, 91, 267 Aguila (ship), 103 Bay of Tapueraha (Tahiti), 104 Air, 46 Bay of Virgins (FatuHiva), 264 Air Moorea, 51 Belvedere Lookout (Moorea), C Air Tahiti, 52, 237 134 Calendar of events, 42–43 Air Tahiti Airpass, 51 Biking and mountain biking, 69 Calvary Cemetery (Atuona), 256 Air Tahiti Nui, 46 Bora Bora, 183 Captain Bligh Restaurant and Air travel, 45–51, 54 Fakarava, 228 Bar (Punaauia), 126 Albert Rent-a-Car (Moorea), 129 Hiva -

Statistiques 1997 France Outre-Mer

MINISTERE DE L’EQUIPEMENT, DES TRANSPORTS ET DU LOGEMENT DIRECTION GENERALE DE L’AVIATION CIVILE DIRECTION DES TRANSPORTS AERIENS SOUS-DIRECTION DES ETUDES ECONOMIQUES ET DE LA PROSPECTIVE BUREAU P1 BULLETIN STATISTIQUE TRAFIC COMMERCIAL ANNEE 1997 JUIN 1998 48, RUE CAMILLE DESMOULINS 92452 ISSY-LES-MOULINEAUX CEDEX - TEL : 01 41 09 49 80 - FAX : 01 41 09 48 83 Le Bulletin Statistique de la Direction Générale de l'Aviation Civile est élaboré à partir des statistiques de trafic commercial provenant de l'ensemble des plates-formes françaises. L'édition de ce bulletin requiert que chacun des aéroports français transmette ses propres données. Tout délai dans la fourniture de celles-ci retarde d’autant la parution de ce bulletin. Des données partielles sont toutefois disponibles beaucoup plus tôt. Dès le mois de mars, certaines d’entre elles peuvent être consultées au Bureau de l'Observation Economique (P1). Il existe enfin des résultats plus détaillés que ceux publiés dans ce bulletin. Ils sont disponibles au Bureau de l'Observation Economique (P1) : 48 rue Camille DESMOULINS 92452 ISSY LES MOULINEAUX CEDEX Téléphone : 01 41 09 49 81 Télécopie : 01 41 09 48 83 A AVERTISSEMENT Les résultats des tableaux sont établis par traitement des formulaires de trafic remplis sur les aérodromes par les gestionnaires, les représentants des transporteurs et les personnels de la DGAC. DEFINITIONS Desserte : vol desservant, suivant le cas, une escale, une étape, une ligne ou une relation Escale : aérodrome relatif au mouvement d'un appareil Etape : trajet entre deux escales consécutives Faisceau : groupe de lignes appartenant a un même secteur géographique Ligne : suite fixe et ordonnée d'escales reliées par un même vol Mouvement d'appareil : atterrissage ou décollage P.K.T. -

7340.2F W Chgs 1-3 Eff 9-15-16

RECORD OF CHANGES DIRECTIVE NO. JO 7340.2F CHANGE SUPPLEMENTS CHANGE SUPPLEMENTS TO OPTIONAL TO OPTIONAL BASIC BASIC FAA Form 1320−5 (6−80) USE PREVIOUS EDITION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2F CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION CHG 3 Air Traffic Organization Policy Effective Date: September 15, 2016 SUBJ: Contractions 1. Purpose of This Change. This change transmits revised pages to Federal Aviation Administration Order JO 7340.2F, Contractions. 2. Audience. This change applies to all Air Traffic Organization (ATO) personnel and anyone using ATO directives. 3. Where Can I Find This Change? This change is available on the FAA Web site at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications and https://employees.faa.gov/tools_resources/orders_notices/. 4. Distribution. This change is distributed to selected offices in Washington headquarters, regional offices, service area offices, the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center; to all field offices and field facilities; to all airway facilities field offices; to all international aviation field offices, airport district offices, and flight standards district offices; and to interested aviation public. 5. Disposition of Transmittal. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. Page Control Chart. See the page control chart attachment. Distribution: ZAT-734, ZAT-464 Initiated By: AJV-0 Vice President, Mission Support Services 9/15/16 JO 7340.2F CHG 3 PAGE CONTROL CHART Change 3 REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED Subscription Information ................ 10/15/15 Subscription Information ............... 9/15/16 Table of Contents i and ii ............... 5/26/16 Table of Contents i and ii .............