A Stone in the Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

CONSULTATIVE GROUP ON INTERNATIONAL AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Fulfilling the Susan Whelan Promise: the Role for Public Disclosure Authorized 2003 Sir John Crawford Memorial Lecture Agricultural Research CGIAR Public Disclosure Authorized Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) is a strategic alliance of countries, international and regional organizations, and private foundations supporting 16 international agricultural research Centers that work with national agricultural systems, the private sector and civil society. The alliance mobilizes agricultural science to reduce poverty, foster human well-being, promote agricultural growth, and protect the environment. The CGIAR generates global public goods which are available to all. www.cgiar.org Fulfilling the Promise: the Role for Agricultural Research By Susan Whelan Minister for International Cooperation Canada 2003 Sir John Crawford Memorial Lecture Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research Nairobi, Kenya October 29, 2003 02 Ministers, Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen, good afternoon. Bonjour. Buenos Dias. Hamjambuni. Many distinguished speakers have stood behind this podium since the inaugural Sir John Crawford Memorial Lecture in 1985. It is with a sense of humility that I accept the honor to be numbered among them. As I do so, I would like to thank the Government of Australia for sponsoring this lecture and take a minute to reflect on the life and work of Sir John and on the reasons why funds, prizes and at least two lectures have been named in his honor. 03 I have not had the privilege of a personal acquaintance with Sir John. However, I admire the simple yet noble and profound proposition or objective on which this great gentleman built his sterling contribution to international development. -

The Victims of Substantive Representation: How "Women's Interests" Influence the Career Paths of Mps in Canada (1997-2011)

The Victims of Substantive Representation: How "Women's Interests" Influence the Career Paths of MPs in Canada (1997-2011) by Susan Piercey A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Department of Political Science Memorial University September, 2011 St. John's Newfoundland Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre r&tirence ISBN: 978-0-494-81979-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-81979-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

On Multiculturalism's Margins: Oral History and Afghan Former

On Multiculturalism’s Margins: Oral History and Afghan Former Refugees in Early Twenty-first Century Winnipeg By Allison L. Penner A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of History Joint Master’s Program University of Manitoba / University of Winnipeg Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2019 by Allison L. Penner Abstract Oral historians have long claimed that oral history enables people to present their experiences in an authentic way, lauding the potential of oral history to ‘democratize history’ and assist interviewees, particularly those who are marginalized, to ‘find their voices’. However, stories not only look backward at the past but also locate the individual in the present. As first demonstrated by Edward Said in Orientalism, Western societies have a long history of Othering non-Western cultures and people. While significant scholarly attention has been paid to this Othering, the responses of orientalised individuals (particularly those living in the West) have received substantially less attention. This thesis focuses on the multi-sessional life story oral history interviews that I conducted with five Afghan-Canadians between 2012 and 2015, most of whom came to Canada as refugees. These interviews were conducted during the Harper era, when celebrated Canadian notions of multiculturalism, freedom, and equality existed alongside Orientalist discourses about immigrants, refugees, Muslims, and Afghans. News stories and government policies and legislation highlighted the dangers that these groups posed to the Canadian public, ‘Canadian’ values, and women. Drawing on the theoretical work of notable oral historians including Mary Chamberlain and Alessandro Portelli, I consider the ways in which the narrators talked about themselves and their lives in light of these discourses. -

Tuesday, June 8, 1999

CANADA VOLUME 135 S NUMBER 240 S 1st SESSION S 36th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Tuesday, June 8, 1999 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire'' at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 15957 HOUSE OF COMMONS Tuesday, June 8, 1999 The House met at 10 a.m. International Space Station and to make related amendments to other Acts. _______________ (Motions deemed adopted, bill read the first time and printed) Prayers * * * _______________ PETITIONS ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS CHILD PORNOGRAPHY Mr. Werner Schmidt (Kelowna, Ref.): Mr. Speaker, it is D (1005) indeed an honour and a privilege to present some 3,000-plus [Translation] petitioners who have come to the House with a petition. They would request that parliament take all measures necessary to GOVERNMENT RESPONSE TO PETITIONS ensure that possession of child pornography remains a serious criminal offence, and that federal police forces be directed to give Mr. Peter Adams (Parliamentary Secretary to Leader of the priority to enforcing this law for the protection of our children. Government in the House of Commons, Lib.): Mr. Speaker, pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), I have the honour to table, in This is a wonderful petition and I endorse it 100%. both official languages, the government’s response to 10 petitions. THE CONSTITUTION * * * Mr. Svend J. Robinson (Burnaby—Douglas, NDP): Mr. [English] Speaker, I am presenting two petitions this morning. The first petition has been signed by residents of my constituency of COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE Burnaby—Douglas as well as communities across Canada. -

Hiv/Aids and the Humanitarian Catastrophe in Sub-Saharan Africa

HOUSE OF COMMONS CANADA HIV/AIDS AND THE HUMANITARIAN CATASTROPHE IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA REPORT OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE Bernard Patry, M.P. Chair Irwin Cotler, M.P. Chair Sub-Committee on Human Rights and International Development June 2003 The Speaker of the House hereby grants permission to reproduce this document, in whole or in part for use in schools and for other purposes such as private study, research, criticism, review or newspaper summary. Any commercial or other use or reproduction of this publication requires the express prior written authorization of the Speaker of the House of Commons. If this document contains excerpts or the full text of briefs presented to the Committee, permission to reproduce these briefs, in whole or in part, must be obtained from their authors. Also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire: http://www.parl.gc.ca Available from Communication Canada — Publishing, Ottawa, Canada K1A 0S9 HIV/AIDS AND THE HUMANITARIAN CATASTROPHE IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA REPORT OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE Bernard Patry, M.P. Chair Irwin Cotler, M.P. Chair Sub-Committee on Human Rights and International Development June 2003 STANDING COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE CHAIR Bernard Patry VICE-CHAIRS Hon. Diane Marleau Stockwell Day MEMBERS Stéphane Bergeron John Harvard Murray Calder André Harvey Aileen Carroll Francine Lalonde Bill Casey Keith Martin Irwin Cotler Alexa McDonough John Duncan Deepak Obhrai Hon. -

In a Constant State of Flux: the Cultural Hybrid Identities of Second-Generation Afghan-Canadian Women

IN A CONSTANT STATE OF FLUX: THE CULTURAL HYBRID IDENTITIES OF SECOND-GENERATION AFGHAN-CANADIAN WOMEN By: Saher Malik Ahmed, B. A A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Post-Doctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Women’s and Gender Studies Pauline Jewett Institute of Women’s and Gender Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario July 2016 © 2016 Saher Malik Ahmed Abstract This study, guided by feminist methodology and cultural hybrid theory, explores the experiences of Afghan-Canadian women in Ottawa, Ontario who identify as second- generation. A qualitative approach using in-depth interviews with ten second-generation Afghan-Canadian women reveals how these women are continuously constructing their hybrid identities through selective acts of cultural negotiation and resistance. This study will examine the transformative and dynamic interplay of balancing two contrasting cultural identities, Afghan and Canadian. The findings will reveal new meanings within the Afghan diaspora surrounding Afghan women’s gender roles and their strategic integration into Canadian society. i Acknowledgments I am deeply indebted to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Amrita Hari. I thank her sincerely for her endless guidance, patience, and encouragement throughout my graduate studies. I have benefited from her wisdom and insightful feedback that has helped me develop strong research and academic skills, and for this I am immensely grateful. I would like to thank Dr. Karen March, my thesis co-supervisor for her incisive comments and challenging questions. I will never forget the conversation I had with her on the phone during the early stages of my research when she reminded me of the reasons why and for whom this research is intended. -

SREC Cleared Protocols

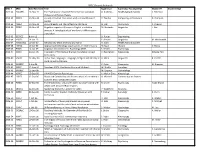

SREC Cleared Protocols SREC # SREC Date Received Title Supervisor Supervisor Faculty/Dept Student PI Student Dept 2012 64 HASSREC 16-Nov-12 The Psychosocial impact of Retirement on Canadian G. Andrews Health,Aging & Society S. Paterson Professional Hockey Players 2012 63 KSREC 16-Nov-12 A study of human interaction with a virtual 3D world R. Teather Computing and Software G. Patriquin builder 2012 65 PSREC 19-Nov-12 Binaural Beats and Their Effects on Vigilance G. Hall Psychology A. Cheung 2012 66 PSREC 19-Nov-12 Cognitive aspects of Korean-to-English translation M. Stroinska Linguistics J. Kim process: A Translog study of word order differences in translation 2013 03 BESREC 8-Jan-13 D. Potter Engineering 2013 04 HSREC 14-Jan-13 E. Service Linguistics M. MacDonald 2009 04 HASGSREC 13-Jan-09 Gerontology 3H03: Diversity and Aging A. Joshi Health,Aging & Society 2009 05 HSREC 13-Jan-09 Appropriate technology organizations in recent history M. Egan History V. Rocca 2009 06 PSREC 14-Jan-09 Cognitive Neuroscience II: Psychology 4BN3 S. Becker Psychology 2006 37 KSREC 20-Apr-06 The realm of HIV/AIDS at the Naz Foundation in New B. Henderson Kinesiology Nitasha Puri Delhi, India 2006 40 HSREC 23-May-06 In Our Own Languages: Language, Religion and Identity in A. Moro Linguistics B. Chettle Local Immigrant Groups 2006 41 GGSREC 5-Jun-06 C. Eyles Geography M. Stoesser 2006 42 SSREC 25-Aug-06 Sociology 3O03: Qualitative Research Methods W. Shaffir Sociology 2006 43 GGSREC 11-Sep-06 M. Grignon Gerontology 2006 44 KSREC 15-Sep-06 KIN 4I03: Exercise Psychology K. -

Friday, October 2, 1998

CANADA VOLUME 135 S NUMBER 131 S 1st SESSION S 36th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, October 2, 1998 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire'' at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 8689 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, October 2, 1998 The House met at 10 a.m. An hon. member: Let us not exaggerate. _______________ Hon. Don Boudria: —in its supposed wisdom, to resort to a procedural mechanism so as to prevent the bill from going forward. Prayers The opposition has asked that consideration of the bill to help small businesses be postponed for six months. _______________ Hon. Lucienne Robillard: What a contradiction! GOVERNMENT ORDERS Hon. Don Boudria: The Minister of Citizenship and Immigra- tion points out how contradictory this is. She is, as usual, right on the mark. D (1005) It is important that this bill to help small businesses go ahead. [English] [English] CANADA SMALL BUSINESS FINANCING ACT It is important that the opposition not cause delays on this bill by The House resumed from September 29 consideration of the moving dilatory motions, hoist motions or other procedural tricks motion that Bill C-53, an act to increase the availability of to stop this bill from going ahead. I do not think procedural tricks financing for the establishment, expansion, modernization and should be going on. Therefore I move: improvement of small businesses, be read the second time and That the question be now put. referred to a committee. -

Identity Formation and Negotiation of Afghan Female Youth . in Ontario

Identity Formation and Negotiation of Afghan Female Youth . in Ontario Tabasum Akseer, B.A. Department of Graduate and Undergraduate Studies in Education . Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education · Faculty of Education, Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © Tabasum Akseer, 2011 Abstract The following thesis provides an empirical case study in which a group of 6 first generation female Afghan Canadian youth is studied to determine their identity negotiation and development processes in everyday experiences. This process is investigated across different contexts of home, school, and the community. In tenns of schooling experiences, 2 participants each are selected representing public, Islamic, and Catholic schools in Southern Ontario. This study employs feminist research methods and is analyzed through a convergence of critical race theory (critical race feminism), youth development theory, and feminist theory. Participant experiences reveal issues of racism, discrimination, and bias within schooling (public, Catholic) systems. Within these contexts, participants suppress their identities or are exposed to negative experiences based on their ethnic or religious identification. Students in Islamic schools experience support for a more positive ethnic and religious identity. Home and community provided nurturing contexts where participants are able to reaffirm and develop a positive overall identity. 11 Ackilowledgements My Lord, increase me in knowledge (Quran 20:114) This thesis is first and foremost dedicated to my loving parents, Dr. M. Ahmad Akseer and Ambara Akseer. Thank you for your support throughout the years. My achievements are a reflection of the excellent guidance and support I have received from my family. Thank you especially to my eldest sibling Kamilla who has been a role model since the beginning. -

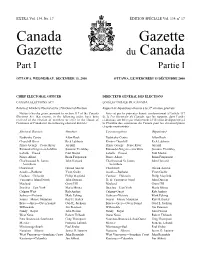

Canada Gazette, Part I, Extra

EXTRA Vol. 134, No. 17 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 134, no 17 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2000 OTTAWA, LE MERCREDI 13 DÉCEMBRE 2000 CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members Elected at the 37th General Election Rapport de députés(es) élus(es) à la 37e élection générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Canada Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’article 317 Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, have been delaLoi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, dans l’ordre received of the election of members to serve in the House of ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élection de députés(es) à Commons of Canada for the following electoral districts: la Chambre des communes du Canada pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral Districts Members Circonscriptions Députés(es) Etobicoke Centre Allan Rock Etobicoke-Centre Allan Rock Churchill River Rick Laliberte Rivière Churchill Rick Laliberte Prince George—Peace River Jay Hill Prince George—Peace River Jay Hill Rimouski-Neigette-et-la Mitis Suzanne Tremblay Rimouski-Neigette-et-la Mitis Suzanne Tremblay LaSalle—Émard Paul Martin LaSalle—Émard Paul Martin Prince Albert Brian Fitzpatrick Prince Albert Brian Fitzpatrick Charleswood St. James— John Harvard Charleswood St. James— John Harvard Assiniboia Assiniboia Charlevoix Gérard Asselin Charlevoix Gérard Asselin Acadie—Bathurst Yvon Godin Acadie—Bathurst Yvon Godin Cariboo—Chilcotin Philip Mayfield Cariboo—Chilcotin Philip Mayfield Vancouver Island North John Duncan Île de Vancouver-Nord John Duncan Macleod Grant Hill Macleod Grant Hill Beaches—East York Maria Minna Beaches—East York Maria Minna Calgary West Rob Anders Calgary-Ouest Rob Anders Sydney—Victoria Mark Eyking Sydney—Victoria Mark Eyking Souris—Moose Mountain Roy H. -

Hansard 33 1..154

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 137 Ï NUMBER 108 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 37th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, November 2, 2001 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 6871 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, November 2, 2001 The House met at 10 a.m. Rights Tribunal and to make consequential amendments to other acts, as reported (with amendments) from the committee. Prayers Hon. Don Boudria (for the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development) moved that the bill, as amended, be concurred in. GOVERNMENT ORDERS (Motion agreed to) The Deputy Speaker: When shall the bill be read the third time? Ï (1000) By leave, now? [English] Some hon. members: Agreed. MISCELLANEOUS STATUTE LAW AMENDMENT ACT, Hon. Don Boudria (for the Minister of Indian Affairs and 2001 Northern Development) moved that the bill be read the third time Hon. Don Boudria (for the Minister of Justice) moved that Bill and passed. C-40, an act to correct certain anomalies, inconsistencies and errors Mr. John Finlay (Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of and to deal with other matters of a non-controversial and Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Lib.): Mr. Speaker, I uncomplicated nature in the Statutes of Canada and to repeal certain am pleased to speak to the bill at third reading because it is of very provisions that have expired, lapsed, or otherwise ceased to have great importance to the people of Nunavut. -

Women As Executive Leaders: Canada in the Context of Anglo-Almerican Systems*

Women as Executive Leaders: Canada in the Context of Anglo-Almerican Systems* Patricia Lee Sykes American University Washington DC [email protected] *Not for citation without permission of the author. Paper prepared for delivery at the Canadian Political Science Association Annual Conference and the Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences, Concordia University, Montreal, June 1-3, 2010. Abstract This research identifies the obstacles and opportunities women as executives encounter and explores when, why, and how they might engender change by advancing the interests and enhancing the status of women as a group. Various positions of executive leadership provide a range of opportunities to investigate and analyze the experiences of women – as prime ministers and party leaders, cabinet ministers, governors/premiers/first ministers, and in modern (non-monarchical) ceremonial posts. Comparative analysis indicates that the institutions, ideology, and evolution of Anglo- American democracies tend to put women as executive leaders at a distinct disadvantage. Placing Canada in this context reveals that its female executives face the same challenges as women in other Anglo countries, while Canadian women also encounter additional obstacles that make their environment even more challenging. Sources include parliamentary records, government documents, public opinion polls, news reports, leaders’ memoirs and diaries, and extensive elite interviews. This research identifies the obstacles and opportunities women as executives encounter and explores when, why, and how they might engender change by advancing the interests and enhancing the status of women. Comparative analysis indicates that the institutions, ideology, and evolution of Anglo-American democracies tend to put women as executive leaders at a distinct disadvantage.