On Multiculturalism's Margins: Oral History and Afghan Former

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Immigrant to Citizen in a Multicultural Country

Social Inclusion (ISSN: 2183–2803) 2018, Volume 6, Issue 3, Pages 229–236 DOI: 10.17645/si.v6i3.1523 Article Passing the Test? From Immigrant to Citizen in a Multicultural Country Elke Winter Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON K1N 6N5, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 3 April 2018 | Accepted: 15 May 2018 | Published: 30 August 2018 Abstract Almost all Western countries have recently implemented restrictive changes to their citizenship law and engaged in heated debates about what it takes to become “one of us”. This article examines the naturalization process in Canada, a country that derives almost two thirds of its population growth from immigration, and where citizenship uptake is currently in decline. Drawing on interviews with recently naturalized Canadians, I argue that the current naturalization regime fails to deliver on the promise to put “Canadians by choice” at par with “Canadians by birth”. Specifically, the naturalization process constructs social and cultural boundaries at two levels: the new citizens interviewed for this study felt that the nat- uralization process differentiated them along the lines of class and education more than it discriminated on ethnocultural or racial grounds. A first boundary is thus created between those who have the skills to easily “pass the test” and those who do not. This finding speaks to the strength and appeal of Canada’s multicultural middle-class nation-building project. Nevertheless, the interviewees also highlighted that the naturalization process artificially constructed (some) immigrants as culturally different and inferior. A second boundary is thus constructed to differentiate between “real Canadians” and others. -

Ishaq V Canada: “Social Science Facts” in Feminist Interventions Dana Phillips

Document generated on 09/25/2021 1:10 p.m. Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice Recueil annuel de Windsor d'accès à la justice Ishaq v Canada: “Social Science Facts” in Feminist Interventions Dana Phillips Volume 35, 2018 Article abstract This article examines the role of social science in feminist intervener advocacy, URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1057069ar focusing on the 2015 case ofIshaq v Canada (Minister of Citizenship and DOI: https://doi.org/10.22329/wyaj.v35i0.5271 Immigration). InIshaq, a Muslim woman challenged a Canadian government policy requiring her to remove her niqab while reciting the citizenship oath. See table of contents The Federal Court of Appeal dismissed several motions for intervention by feminist and other equality-seeking organizations, emphasizing their improper reliance on unproven social facts and social science research. I argue that this Publisher(s) decision departs from the generous approach to public interest interventions sanctioned by the federal and other Canadian courts. More importantly, the Faculty of Law, University of Windsor Court’s characterization of the intervener submissions as relying on “social science facts” that must be established through the evidentiary record ISSN diminishes the capacity of feminist interveners to effectively support equality and access to justice for marginalized groups in practice. 2561-5017 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Phillips, D. (2018). Ishaq v Canada: “Social Science Facts” in Feminist Interventions. Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice / Recueil annuel de Windsor d'accès à la justice, 35, 99–126. https://doi.org/10.22329/wyaj.v35i0.5271 Copyright (c), 2019 Dana Phillips This document is protected by copyright law. -

Forensic Mental Health Evaluations in the Guantánamo Military Commissions System: an Analysis of All Detainee Cases from Inception to 2018 T ⁎ Neil Krishan Aggarwal

International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 64 (2019) 34–39 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Law and Psychiatry journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijlawpsy Forensic mental health evaluations in the Guantánamo military commissions system: An analysis of all detainee cases from inception to 2018 T ⁎ Neil Krishan Aggarwal Clinical Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Medical Center, Committee on Global Thought, Columbia University, New York State Psychiatric Institute, United States ABSTRACT Even though the Bush Administration opened the Guantánamo Bay detention facility in 2002 in response to the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States, little remains known about how forensic mental health evaluations relate to the process of detainees who are charged before military commissions. This article discusses the laws governing Guantánamo's military commissions system and mental health evaluations. Notably, the US government initially treated detaineesas“unlawful enemy combatants” who were not protected under the US Constitution and the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Forms of Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment, allowing for the use of “enhanced interrogation techniques.” In subsequent legal documents, however, the US government has excluded evidence obtained through torture, as defined by the US Constitution and the United Nations Convention Against Torture. Using open-source document analysis, this article describes the reasons and outcomes of all forensic mental health evaluations from Guantánamo's opening to 2018. Only thirty of 779 detainees (~3.85%) have ever had charges referred against them to the military commissions, and only nine detainees (~1.16%) have ever received forensic mental health evaluations pertaining to their case. -

Unclassified//For Public Release Unclassified//For Public Release

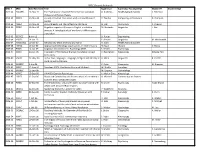

UNCLASSIFIED//FOR PUBLIC RELEASE --SESR-Efll-N0F0RN- Final Dispositions as of January 22, 2010 Guantanamo Review Dispositions Country ISN Name Decision of Origin AF 4 Abdul Haq Wasiq Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 6 Mullah Norullah Noori Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 7 Mullah Mohammed Fazl Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001 ), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 560 Haji Wali Muhammed Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001 ), as informed by principles of the laws of war, subject to further review by the Principals prior to the detainee's transfer to a detention facility in the United States. AF 579 Khairullah Said Wali Khairkhwa Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 753 Abdul Sahir Referred for prosecution. AF 762 Obaidullah Referred for prosecution. AF 782 Awai Gui Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 832 Mohammad Nabi Omari Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001 ), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 850 Mohammed Hashim Transfer to a country outside the United States that will implement appropriate security measures. AF 899 Shawali Khan Transfer to • subject to appropriate security measures. -

FOIA) Document Clearinghouse in the World

This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com Received Received Request ID Requester Name Organization Closed Date Final Disposition Request Description Mode Date 17-F-0001 Greenewald, John The Black Vault PAL 10/3/2016 11/4/2016 Granted/Denied in Part I respectfully request a copy of records, electronic or otherwise, of all contracts past and present, that the DOD / OSD / JS has had with the British PR firm Bell Pottinger. Bell Pottinger Private (legally BPP Communications Ltd.; informally Bell Pottinger) is a British multinational public relations and marketing company headquartered in London, United Kingdom. 17-F-0002 Palma, Bethania - PAL 10/3/2016 11/4/2016 Other Reasons - No Records Contracts with Bell Pottinger for information operations and psychological operations. (Date Range for Record Search: From 01/01/2007 To 12/31/2011) 17-F-0003 Greenewald, John The Black Vault Mail 10/3/2016 1/13/2017 Other Reasons - Not a proper FOIA I respectfully request a copy of the Intellipedia category index page for the following category: request for some other reason Nuclear Weapons Glossary 17-F-0004 Jackson, Brian - Mail 10/3/2016 - - I request a copy of any available documents related to Army Intelligence's participation in an FBI counterintelligence source operation beginning in about 1959, per David Wise book, "Cassidy's Run," under the following code names: ZYRKSEEZ SHOCKER I am also interested in obtaining Army Intelligence documents authorizing, as well as policy documents guiding, the use of an Army source in an FBI operation. -

United States of America: Compliance with the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict

United States of America: Compliance with the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict Submission to the Committee on the Rights of the Child from Human Rights Watch and Human Rights First April 2012 Summary Since its initial report and review in 2008, the United States has taken important steps to prevent the deployment of 17-year-old soldiers to areas of hostilities and has improved its oversight of, and response to, incidents of recruiter irregularities and misconduct. It has enacted new legislation intended to prevent the recruitment and use of child soldiers, including the Child Soldiers Accountability Act of 2008 and the Child Soldiers Prevention Act of 2008. In 2012, the Child Soldiers Accountability Act was used for the first time when a former military commander from Liberia was ordered deported by an immigration judge. In 2011, under the Child Soldiers Prevention Act, the US acted to withhold US$2.7 million in foreign military financing from the government of the Democratic Republic of Congo until the Congolese armed forces took steps to end its recruitment and use of child soldiers. The United States continued to provide support internationally for rehabilitation and reintegration programs for former child soldiers. Despite positive steps, concerns regarding US implementation of its obligations under the Optional Protocol include: Recruiter misconduct: Although substantiated cases of recruitment misconduct make up a very small percentage of total recruitment cases, reports still indicate that recruiters may falsify 1 documents, fail to obtain parental consent for underage recruits, and engage in sexual misconduct with girls under age 18. -

A Stone in the Water

A STONE IN THE WATER Report of the Roundtables with Afghan-Canadian Women On the Question of the Application UN Security Council Resolution 1325 in Afghanistan July 2002 Organized by the The Honourable Mobina S.B. Jaffer of the Advocacy Subcommittee of the Canadian Committee on Women, Peace and Security in partnership with the YWCA of Canada With Financial Support from the Human Security Program of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Canada We acknowledge The Aga Khan Council for Ontario for their support in this initiative 0 Speechless At home, I speak the language of the gender that is better than me. In the mosque, I speak the language of the nation that is better than me. Outside, I speak the language of those who are the better race. I am a non-Arabic Muslim woman who lives in a Western country. Fatema, poet, Toronto 1 Dedication This report is dedicated to the women and girls living in Afghanistan, and the future which can be theirs 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY…………………………………………………………insert BACKGROUND……………………………………………………………………...….4 OBJECTIVES……...………………………………………………………………….…9 REPORT………………………………………………………………………………...11 Introduction………………………………………………………………………11 What Are The Barriers to the Full Participation of Women in Afghan Society (Question 1)…………………………………….……………13 Personal Safety and Security…………………………………………………….13 Warlords…………………………………………………………………14 Lack of Civilian Police Force and Army………………………………...15 Justice and Accountability……………………………………………………….16 Education……………………………………………………………………..….18 -

Regarding D-017, the Defense Motion for a Continuance Is Denied

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA D-022 RULING ON DEFENSE MOTION v. TO SUPPRESS OUT-OF-COURT STATEMENTS OF THE ACCUSED TO MOHAMMED JAWAD AFGHAN AUTHORITIES ________________________________________________________________ 1. On or about December 17, 2002, in Kabul, Afghanistan, the Accused allegedly threw a hand grenade into a vehicle in which two American service members and their Afghan interpreter were riding. All suffered serious injuries. The Accused, at the time under the age of 18 years,1 was subsequently apprehended by Afghan police and transported to an Afghan police station for interrogation. The Accused appeared to be under the influence of drugs. Present at the police station were several high-ranking Afghan government officials, including the Interior Minister, the Police and Security Commander, and the Criminal Investigations Director. Most, if not all, present were carrying firearms, which were visible to the Accused. During the interrogation, someone told the Accused, “You will be killed if you do not confess to the grenade attack,” and, “We will arrest your family and kill them if you do not confess,” or words to that effect.2 The speaker meant what he said; it was a credible threat. The 1 The government has implicitly conceded that, at the time of the charged offenses, the Accused was less than 18 years old. Specifically, the United States has stated: “At Guantanamo, the United States is detaining Omar Khadr and Mohammed Jawad, the only two individuals captured when they were under the age of 18, whom the United States Government has chosen to prosecute under the Military Commissions Act of 2006.” See United States Written Response to Questions Asked by the Committee on the Rights of the Child, 13 May 2008, available at: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/105437.htm (last visited 16 September 2008). -

In a Constant State of Flux: the Cultural Hybrid Identities of Second-Generation Afghan-Canadian Women

IN A CONSTANT STATE OF FLUX: THE CULTURAL HYBRID IDENTITIES OF SECOND-GENERATION AFGHAN-CANADIAN WOMEN By: Saher Malik Ahmed, B. A A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Post-Doctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Women’s and Gender Studies Pauline Jewett Institute of Women’s and Gender Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario July 2016 © 2016 Saher Malik Ahmed Abstract This study, guided by feminist methodology and cultural hybrid theory, explores the experiences of Afghan-Canadian women in Ottawa, Ontario who identify as second- generation. A qualitative approach using in-depth interviews with ten second-generation Afghan-Canadian women reveals how these women are continuously constructing their hybrid identities through selective acts of cultural negotiation and resistance. This study will examine the transformative and dynamic interplay of balancing two contrasting cultural identities, Afghan and Canadian. The findings will reveal new meanings within the Afghan diaspora surrounding Afghan women’s gender roles and their strategic integration into Canadian society. i Acknowledgments I am deeply indebted to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Amrita Hari. I thank her sincerely for her endless guidance, patience, and encouragement throughout my graduate studies. I have benefited from her wisdom and insightful feedback that has helped me develop strong research and academic skills, and for this I am immensely grateful. I would like to thank Dr. Karen March, my thesis co-supervisor for her incisive comments and challenging questions. I will never forget the conversation I had with her on the phone during the early stages of my research when she reminded me of the reasons why and for whom this research is intended. -

SREC Cleared Protocols

SREC Cleared Protocols SREC # SREC Date Received Title Supervisor Supervisor Faculty/Dept Student PI Student Dept 2012 64 HASSREC 16-Nov-12 The Psychosocial impact of Retirement on Canadian G. Andrews Health,Aging & Society S. Paterson Professional Hockey Players 2012 63 KSREC 16-Nov-12 A study of human interaction with a virtual 3D world R. Teather Computing and Software G. Patriquin builder 2012 65 PSREC 19-Nov-12 Binaural Beats and Their Effects on Vigilance G. Hall Psychology A. Cheung 2012 66 PSREC 19-Nov-12 Cognitive aspects of Korean-to-English translation M. Stroinska Linguistics J. Kim process: A Translog study of word order differences in translation 2013 03 BESREC 8-Jan-13 D. Potter Engineering 2013 04 HSREC 14-Jan-13 E. Service Linguistics M. MacDonald 2009 04 HASGSREC 13-Jan-09 Gerontology 3H03: Diversity and Aging A. Joshi Health,Aging & Society 2009 05 HSREC 13-Jan-09 Appropriate technology organizations in recent history M. Egan History V. Rocca 2009 06 PSREC 14-Jan-09 Cognitive Neuroscience II: Psychology 4BN3 S. Becker Psychology 2006 37 KSREC 20-Apr-06 The realm of HIV/AIDS at the Naz Foundation in New B. Henderson Kinesiology Nitasha Puri Delhi, India 2006 40 HSREC 23-May-06 In Our Own Languages: Language, Religion and Identity in A. Moro Linguistics B. Chettle Local Immigrant Groups 2006 41 GGSREC 5-Jun-06 C. Eyles Geography M. Stoesser 2006 42 SSREC 25-Aug-06 Sociology 3O03: Qualitative Research Methods W. Shaffir Sociology 2006 43 GGSREC 11-Sep-06 M. Grignon Gerontology 2006 44 KSREC 15-Sep-06 KIN 4I03: Exercise Psychology K. -

Legislative Summary of Bill C-75 (Legislative Summary)

Bill C-75: An Act to amend the Citizenship Act and to make a consequential amendment to another Act Publication No. 41-2-C75-E 29 June 2015 Justin Mohammed Economics, Resources and International Affairs Division Parliamentary Information and Research Service Library of Parliament Legislative Summaries summarize government bills currently before Parliament and provide background about them in an objective and impartial manner. They are prepared by the Parliamentary Information and Research Service, which carries out research for and provides information and analysis to parliamentarians and Senate and House of Commons committees and parliamentary associations. Legislative Summaries are revised as needed to reflect amendments made to bills as they move through the legislative process. Notice: For clarity of exposition, the legislative proposals set out in the bill described in this Legislative Summary are stated as if they had already been adopted or were in force. It is important to note, however, that bills may be amended during their consideration by the House of Commons and Senate, and have no force or effect unless and until they are passed by both houses of Parliament, receive Royal Assent, and come into force. Any substantive changes in this Legislative Summary that have been made since the preceding issue are indicated in bold print. © Library of Parliament, Ottawa, Canada, 2015 Legislative Summary of Bill C-75 (Legislative Summary) Publication No. 41-2-C75-E Ce document est également publié en français. CONTENTS 1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................ -

Identity Formation and Negotiation of Afghan Female Youth . in Ontario

Identity Formation and Negotiation of Afghan Female Youth . in Ontario Tabasum Akseer, B.A. Department of Graduate and Undergraduate Studies in Education . Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education · Faculty of Education, Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © Tabasum Akseer, 2011 Abstract The following thesis provides an empirical case study in which a group of 6 first generation female Afghan Canadian youth is studied to determine their identity negotiation and development processes in everyday experiences. This process is investigated across different contexts of home, school, and the community. In tenns of schooling experiences, 2 participants each are selected representing public, Islamic, and Catholic schools in Southern Ontario. This study employs feminist research methods and is analyzed through a convergence of critical race theory (critical race feminism), youth development theory, and feminist theory. Participant experiences reveal issues of racism, discrimination, and bias within schooling (public, Catholic) systems. Within these contexts, participants suppress their identities or are exposed to negative experiences based on their ethnic or religious identification. Students in Islamic schools experience support for a more positive ethnic and religious identity. Home and community provided nurturing contexts where participants are able to reaffirm and develop a positive overall identity. 11 Ackilowledgements My Lord, increase me in knowledge (Quran 20:114) This thesis is first and foremost dedicated to my loving parents, Dr. M. Ahmad Akseer and Ambara Akseer. Thank you for your support throughout the years. My achievements are a reflection of the excellent guidance and support I have received from my family. Thank you especially to my eldest sibling Kamilla who has been a role model since the beginning.