Diapositiva 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abacca Mosaic Virus

Annex Decree of Ministry of Agriculture Number : 51/Permentan/KR.010/9/2015 date : 23 September 2015 Plant Quarantine Pest List A. Plant Quarantine Pest List (KATEGORY A1) I. SERANGGA (INSECTS) NAMA ILMIAH/ SINONIM/ KLASIFIKASI/ NAMA MEDIA DAERAH SEBAR/ UMUM/ GOLONGA INANG/ No PEMBAWA/ GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENTIFIC NAME/ N/ GROUP HOST PATHWAY DISTRIBUTION SYNONIM/ TAXON/ COMMON NAME 1. Acraea acerata Hew.; II Convolvulus arvensis, Ipomoea leaf, stem Africa: Angola, Benin, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae; aquatica, Ipomoea triloba, Botswana, Burundi, sweet potato butterfly Merremiae bracteata, Cameroon, Congo, DR Congo, Merremia pacifica,Merremia Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, peltata, Merremia umbellata, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ipomoea batatas (ubi jalar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, sweet potato) Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo. Uganda, Zambia 2. Ac rocinus longimanus II Artocarpus, Artocarpus stem, America: Barbados, Honduras, Linnaeus; Coleoptera: integra, Moraceae, branches, Guyana, Trinidad,Costa Rica, Cerambycidae; Herlequin Broussonetia kazinoki, Ficus litter Mexico, Brazil beetle, jack-tree borer elastica 3. Aetherastis circulata II Hevea brasiliensis (karet, stem, leaf, Asia: India Meyrick; Lepidoptera: rubber tree) seedling Yponomeutidae; bark feeding caterpillar 1 4. Agrilus mali Matsumura; II Malus domestica (apel, apple) buds, stem, Asia: China, Korea DPR (North Coleoptera: Buprestidae; seedling, Korea), Republic of Korea apple borer, apple rhizome (South Korea) buprestid Europe: Russia 5. Agrilus planipennis II Fraxinus americana, -

Molecular Evolution and Functional Divergence of Tubulin Superfamily In

OPEN Molecular evolution and functional SUBJECT AREAS: divergence of tubulin superfamily in the FUNGAL GENOMICS MOLECULAR EVOLUTION fungal tree of life FUNGAL BIOLOGY Zhongtao Zhao1*, Huiquan Liu1*, Yongping Luo1, Shanyue Zhou2, Lin An1, Chenfang Wang1, Qiaojun Jin1, Mingguo Zhou3 & Jin-Rong Xu1,2 Received 18 July 2014 1 NWAFU-PU Joint Research Center, State Key Laboratory of Crop Stress Biology for Arid Areas, College of Plant Protection, 2 Accepted Northwest A&F University, Yangling, Shaanxi 712100, China, Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Purdue University, West 3 22 September 2014 Lafayette, IN 47907, USA, College of Plant Protection, Nanjing Agricultural University, Key Laboratory of Integrated Management of Crop Diseases and Pests, Ministry of Education, Key Laboratory of Pesticide, Nanjing, Jiangsu 210095, China. Published 23 October 2014 Microtubules are essential for various cellular activities and b-tubulins are the target of benzimidazole fungicides. However, the evolution and molecular mechanisms driving functional diversification in fungal tubulins are not clear. In this study, we systematically identified tubulin genes from 59 representative fungi Correspondence and across the fungal kingdom. Phylogenetic analysis showed that a-/b-tubulin genes underwent multiple requests for materials independent duplications and losses in different fungal lineages and formed distinct paralogous/ should be addressed to orthologous clades. The last common ancestor of basidiomycetes and ascomycetes likely possessed two a a a b b b a J.-R.X. (jinrong@ paralogs of -tubulin ( 1/ 2) and -tubulin ( 1/ 2) genes but 2-tubulin genes were lost in basidiomycetes and b2-tubulin genes were lost in most ascomycetes. Molecular evolutionary analysis indicated that a1, a2, purdue.edu) and b2-tubulins have been under strong divergent selection and adaptive positive selection. -

Fungal Evolution: Major Ecological Adaptations and Evolutionary Transitions

Biol. Rev. (2019), pp. 000–000. 1 doi: 10.1111/brv.12510 Fungal evolution: major ecological adaptations and evolutionary transitions Miguel A. Naranjo-Ortiz1 and Toni Gabaldon´ 1,2,3∗ 1Department of Genomics and Bioinformatics, Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), The Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology, Dr. Aiguader 88, Barcelona 08003, Spain 2 Department of Experimental and Health Sciences, Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), 08003 Barcelona, Spain 3ICREA, Pg. Lluís Companys 23, 08010 Barcelona, Spain ABSTRACT Fungi are a highly diverse group of heterotrophic eukaryotes characterized by the absence of phagotrophy and the presence of a chitinous cell wall. While unicellular fungi are far from rare, part of the evolutionary success of the group resides in their ability to grow indefinitely as a cylindrical multinucleated cell (hypha). Armed with these morphological traits and with an extremely high metabolical diversity, fungi have conquered numerous ecological niches and have shaped a whole world of interactions with other living organisms. Herein we survey the main evolutionary and ecological processes that have guided fungal diversity. We will first review the ecology and evolution of the zoosporic lineages and the process of terrestrialization, as one of the major evolutionary transitions in this kingdom. Several plausible scenarios have been proposed for fungal terrestralization and we here propose a new scenario, which considers icy environments as a transitory niche between water and emerged land. We then focus on exploring the main ecological relationships of Fungi with other organisms (other fungi, protozoans, animals and plants), as well as the origin of adaptations to certain specialized ecological niches within the group (lichens, black fungi and yeasts). -

Asparagus Pests and Diseases by Joan Allen

Asparagus Pests and Diseases By Joan Allen Asparagus is one of the few perennial vegetables and with good care a planting can produce a nice crop for 10-15 years. Part of that good care is keeping pest and disease problems under control. Letting them go can lead to weak plants and poor production, even death of the plants in some cases. Stress due to poor nutrition, drought or other problems can make the plants more susceptible to some diseases too. Because of this, good cultural practices, including a good site for new plantings, are the first step in preventing problems. After that, monitor regularly for common pests and diseases so you can catch any problems early and hopefully prevent them from escalating. Weed control is important for a couple of reasons. One, weeds compete with the crop for water and nutrients. More importantly from a disease perspective, they reduce air flow around the plants or between rows and this results in the asparagus spears or foliage remaining wet for a longer period of time after a rain or irrigation event. This matters because moisture promotes many plant diseases. This article will cover some of the most common pests and diseases of asparagus. If you’re not sure what you’ve got, I’ll finish up with resources for assistance. Insect pests include the common and spotted asparagus beetles, asparagus aphid, cutworms, and Japanese beetles. Diseases that will be covered are Fusarium diseases, rust, and purple spot. Both the common and spotted asparagus beetles (CAB and SAB respectively) overwinter in brushy or wooded areas near the field or garden as adults. -

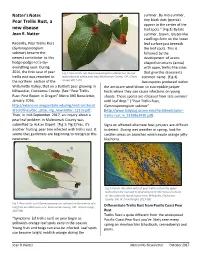

Pear Trellis Rust, a New Disease

Natter’s Notes summer. By mid-summer, Pear Trellis Rust, a tiny black dots (pycnia) appear in the center of the new disease leaf spots.” [Fig 3] By late Jean R. Natter summer, brown, blister-like swellings form on the lower Recently, Pear Trellis Rust leaf surface just beneath (Gymnosporangium the leaf spots. This is sabinae) became the followed by the newest contributor to this development of acorn- hodge-podge-let’s-try- shaped structures (aecia) everything year. During with open, trellis-like sides 2016, the first case of pear Fig 1: Pear trellis rust (Gymnosporangium sabinae) on the top that give this disease its trellis rust was reported in leaf surface of edible pear tree; Multnomah County, OR. (Client common name. (Fig 4) the northern section of the image; 2017-09) Aeciospores produced within Willamette Valley, that on a Bartlett pear growing in the aecia are wind-blown to susceptible juniper Milwaukie, Clackamas County. (See “Pear Trellis hosts where they can cause infections on young Rust: First Report in Oregon” Metro MG Newsletter, shoots. These spores are released from late summer January 2016; until leaf drop.” (“Pear Trellis Rust, http://extension.oregonstate.edu/mg/metro/sites/d Gymnosporangium sabinae” efault/files/dec_2016_mg_newsletter_12116.pdf. (http://www.ladybug.uconn.edu/FactSheets/pear- Then, in mid-September 2017, an inquiry about a trellis-rust_6_2329861430.pdf) pear leaf problem in Multnomah County was submitted to Ask an Expert. [Fig 1; Fig 2] Yes, it’s Signs on affected alternate host junipers are difficult another fruiting pear tree infected with trellis rust. It to detect. -

The Flora Mycologica Iberica Project Fungi Occurrence Dataset

A peer-reviewed open-access journal MycoKeys 15: 59–72 (2016)The Flora Mycologica Iberica Project fungi occurrence dataset 59 doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.15.9765 DATA PAPER MycoKeys http://mycokeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research The Flora Mycologica Iberica Project fungi occurrence dataset Francisco Pando1, Margarita Dueñas1, Carlos Lado1, María Teresa Telleria1 1 Real Jardín Botánico-CSIC, Claudio Moyano 1, 28014, Madrid, Spain Corresponding author: Francisco Pando ([email protected]) Academic editor: C. Gueidan | Received 5 July 2016 | Accepted 25 August 2016 | Published 13 September 2016 Citation: Pando F, Dueñas M, Lado C, Telleria MT (2016) The Flora Mycologica Iberica Project fungi occurrence dataset. MycoKeys 15: 59–72. doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.15.9765 Resource citation: Pando F, Dueñas M, Lado C, Telleria MT (2016) Flora Mycologica Iberica Project fungi occurrence dataset. v1.18. Real Jardín Botánico (CSIC). Dataset/Occurrence. http://www.gbif.es/ipt/resource?r=floramicologicaiberi ca&v=1.18, http://doi.org/10.15468/sssx1e Abstract The dataset contains detailed distribution information on several fungal groups. The information has been revised, and in many times compiled, by expert mycologist(s) working on the monographs for the Flora Mycologica Iberica Project (FMI). Records comprise both collection and observational data, obtained from a variety of sources including field work, herbaria, and the literature. The dataset contains 59,235 records, of which 21,393 are georeferenced. These correspond to 2,445 species, grouped in 18 classes. The geographical scope of the dataset is Iberian Peninsula (Continental Portugal and Spain, and Andorra) and Balearic Islands. The complete dataset is available in Darwin Core Archive format via the Global Biodi- versity Information Facility (GBIF). -

212Asparagus Workshop Part1.Indd

Plant Protection Quarterly Vol.21(2) 2006 63 National Asparagus Weeds Management Workshop Proceedings of a workshop convened by the National Asparagus Weeds Management Committee held in Adelaide on 10–11 November 2005. Editors: John G. Virtue and John K. Scott. Introduction John G. VirtueA and John K. ScottB A Department of Water Land and Biodiversity Conservation, GPO Box 2834, Adelaide, South Australia 5001, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] B CSIRO Entomology, Private Bag 5, PO Wembley, Western Australia 6913, Australia. Welcome to this special issue of Plant Pro- The National Asparagus Weeds Man- authors for the effort they have put into tection Quarterly, which details the current agement Committee (NAWMC) convened their papers and all the workshop par- state of Asparagus weeds management in the National Asparagus Weeds Manage- ticipants for their contribution. A special Australia. Bridal creeper, Asparagus as- ment Workshop in Adelaide, 10–11 No- thanks for workshop organization also paragoides (L.) Druce, is the best known vember 2005. The workshop was attended goes to Dennis Gannaway and Susan Asparagus weed and certainly deserves by 60 people including representation ex- Lawrie. its Weed of National Signifi cance (WoNS) tending from South Africa, through most status in Australia. However, there are regions of continental Australia, to Lord Reference other Asparagus species in Australia that Howe Island in the Pacifi c. The workshop Agriculture & Resource Management have the potential to reach similar levels was made possible with funding assistance Council of Australia & New Zealand, of impact as bridal creeper on biodiversity through the Australian Government’s Nat- Australia & New Zealand Environment (and hence their inclusion in the national ural Heritage Trust. -

Pear Trellis Rust

Dr. Yonghao Li Department of Plant Pathology and Ecology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 123 Huntington Street, P. O. Box 1106 New Haven, CT 06504 Phone: (203) 974-8601 Fax: (203) 974-8502 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: www.ct.gov/caes PEAR TRELLIS RUST Pear trellis rust (European pear rust) is one premature defoliation, significant diebacks, of most devastating diseases on fruit and and reduced tree vigour (Figure 1). ornamental pear trees in Europe. In the United States, since the disease was first SYMPTOMS AND DIAGNOSTICS reported in the Bellingham, WA in 1997, it The disease affects pear and juniper plants, has moved from the west coast to east coast. which is the alternate host of the fungal In Connecticut, pear trellis rust was first pathogen Gymnosporangium sabinae. On reported in 2012. Although the disease is pear trees, the disease mainly damages considered cosmetic on pear trees, heavy and leaves although twigs and fruit can also be repeated infections due to wet spring infected. The initial symptom appears as weather conditions may result in severe yellow spots on the upper side of young leaves in the spring. Lesions become reddish orange in color and expand up to 3/4 inch in diameter (Figure 2). By mid summer, small black dots (spermagonia) form in the center of the spot on the upper side of leaves. And then, light brown, Figure 1. Browning of leaves and early Figure 2. Reddish-brown lesions on the defoliation of heavily infected pear trees in upper- (left) and lower-side (right) of the early summer leaf acorn-shaped structures (aecia) form on the differences in susceptibility between under side of the leaf directly below the varieties. -

Population Biology of Switchgrass Rust

POPULATION BIOLOGY OF SWITCHGRASS RUST (Puccinia emaculata Schw.) By GABRIELA KARINA ORQUERA DELGADO Bachelor of Science in Biotechnology Escuela Politécnica del Ejército (ESPE) Quito, Ecuador 2011 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE July, 2014 POPULATION BIOLOGY OF SWITCHGRASS RUST (Puccinia emaculata Schw.) Thesis Approved: Dr. Stephen Marek Thesis Adviser Dr. Carla Garzon Dr. Robert M. Hunger ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For their guidance and support, I express sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Marek, who has supported thought my thesis with his patience and knowledge whilst allowing me the room to work in my own way. One simply could not wish for a better or friendlier supervisor. I give special thanks to M.S. Maxwell Gilley (Mississippi State University), Dr. Bing Yang (Iowa State University), Arvid Boe (South Dakota State University) and Dr. Bingyu Zhao (Virginia State), for providing switchgrass rust samples used in this study and M.S. Andrea Payne, for her assistance during my writing process. I would like to recognize Patricia Garrido and Francisco Flores for their guidance, assistance, and friendship. To my family and friends for being always the support and energy I needed to follow my dreams. iii Acknowledgements reflect the views of the author and are not endorsed by committee members or Oklahoma State University. Name: GABRIELA KARINA ORQUERA DELGADO Date of Degree: JULY, 2014 Title of Study: POPULATION BIOLOGY OF SWITCHGRASS RUST (Puccinia emaculata Schw.) Major Field: ENTOMOLOGY AND PLANT PATHOLOGY Abstract: Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) is a perennial warm season grass native to a large portion of North America. -

Disease and Insect Pests of Asparagus by William R

Page 1 Disease and insect pests of asparagus by William R. Morrison, III1, Sheila Linderman2, Mary K. Hausbeck2,3, Benjamin P. Werling3 and Zsofia Szendrei1,3 1MSU Department of Entomology; 2MSU Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences; and 3Michigan State University Extension Extension Bulletin E3219 Introduction Biology • Fungus. The goal of this bulletin is to provide basic information • Sexual stage of the fungus (Pleospora herbarum) produc- needed to identify, understand and control insect and es overwintering structures (pseudothecia), appearing as disease pests of asparagus. Because each pest is different, small, black dots on asparagus plant debris from previous control strategies are most effective when they are tai- season. lored to the species present in your production fields. For this reason, this bulletin includes sections on pest identifi- • Pseudothecia release ascospores via rain splash and cation that show key characteristics and pictures to help wind, causing the primary infection for the new season. you determine which pests are present in your asparagus. • Primary infection progresses in the asexual stage of the It is also necessary to understand pests and diseases in fungus (Stemphylium vesicarium), which produces multiple order to appropriately manage them. This bulletin includes spores (conidia) cycles throughout the growing season. sections on the biology of each major insect and disease • Conidia enter plant tissue through wounds and stoma- pest. Finally, it also provides information on cultural and ta, which are pores of a plant used for respiration. general pest control strategies. For specifics on the pesti- • Premature defoliation of the fern limits photosynthetic cides available for chemical control of each pest, consult capability of the plant, decreasing carbohydrate reserves in MSU Extension bulletin E312, “Insect, Disease, and Nema- tode Control for Commercial Vegetables” (Order in the the crown for the following year’s crop. -

Asparagus Rust (Puccinia Asparagi) (Puccinia Matters-Of- Facts Seasons Infection

DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY INDUSTRIES Vegetable Matters-of-Facts Number 12 Asparagus Rust February (Puccinia asparagi) 2004 • Rust disease of asparagus is caused by the fungus Puccinia asparagi. • Rust is only a problem on fern not the spears. • Infected fern is defoliated reducing the potential yield of next seasons crop. • First detected in Queensland in 2000 and in Victoria in 2003 Infection and symptoms Infections of asparagus rust begin in spring from over-wintering spores on crop debris. Rust has several visual spore stages known as the orange, red and black spore stages. Visual symptoms of infection start in spring/summer with light green pustules on new emerging fern which mature into yellow or pale orange pustules. In early to mid summer when conditions are warm and moist, the orange spores spread to new fern growth producing brick red pustules on stalks, branches and leaves of the fern. These develop into powdery masses of rust-red coloured spores which reinfect the fern. Infected fern begins to yellow, defoliate and die back prematurely. In late autumn and winter the red-coloured pustules start to produce black spores and slowly convert in appearance to a powdery mass of jet-black spores. This is the over-wintering stage of Asparagus the fungus and the source of the next seasons infection. Control Stratagies Complete eradication of the disease is not feasible as rust spores are spread by wind. However rust can be controlled with proper fern management. • Scout for early signs for rust and implement fungicide spray program • Volunteer and other unwanted asparagus plantings must be destroyed to control infection sources. -

A Higher-Level Phylogenetic Classification of the Fungi

mycological research 111 (2007) 509–547 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mycres A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi David S. HIBBETTa,*, Manfred BINDERa, Joseph F. BISCHOFFb, Meredith BLACKWELLc, Paul F. CANNONd, Ove E. ERIKSSONe, Sabine HUHNDORFf, Timothy JAMESg, Paul M. KIRKd, Robert LU¨ CKINGf, H. THORSTEN LUMBSCHf, Franc¸ois LUTZONIg, P. Brandon MATHENYa, David J. MCLAUGHLINh, Martha J. POWELLi, Scott REDHEAD j, Conrad L. SCHOCHk, Joseph W. SPATAFORAk, Joost A. STALPERSl, Rytas VILGALYSg, M. Catherine AIMEm, Andre´ APTROOTn, Robert BAUERo, Dominik BEGEROWp, Gerald L. BENNYq, Lisa A. CASTLEBURYm, Pedro W. CROUSl, Yu-Cheng DAIr, Walter GAMSl, David M. GEISERs, Gareth W. GRIFFITHt,Ce´cile GUEIDANg, David L. HAWKSWORTHu, Geir HESTMARKv, Kentaro HOSAKAw, Richard A. HUMBERx, Kevin D. HYDEy, Joseph E. IRONSIDEt, Urmas KO˜ LJALGz, Cletus P. KURTZMANaa, Karl-Henrik LARSSONab, Robert LICHTWARDTac, Joyce LONGCOREad, Jolanta MIA˛ DLIKOWSKAg, Andrew MILLERae, Jean-Marc MONCALVOaf, Sharon MOZLEY-STANDRIDGEag, Franz OBERWINKLERo, Erast PARMASTOah, Vale´rie REEBg, Jack D. ROGERSai, Claude ROUXaj, Leif RYVARDENak, Jose´ Paulo SAMPAIOal, Arthur SCHU¨ ßLERam, Junta SUGIYAMAan, R. Greg THORNao, Leif TIBELLap, Wendy A. UNTEREINERaq, Christopher WALKERar, Zheng WANGa, Alex WEIRas, Michael WEISSo, Merlin M. WHITEat, Katarina WINKAe, Yi-Jian YAOau, Ning ZHANGav aBiology Department, Clark University, Worcester, MA 01610, USA bNational Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information,