Molecular Evolution and Functional Divergence of Tubulin Superfamily In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fungal Evolution: Major Ecological Adaptations and Evolutionary Transitions

Biol. Rev. (2019), pp. 000–000. 1 doi: 10.1111/brv.12510 Fungal evolution: major ecological adaptations and evolutionary transitions Miguel A. Naranjo-Ortiz1 and Toni Gabaldon´ 1,2,3∗ 1Department of Genomics and Bioinformatics, Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), The Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology, Dr. Aiguader 88, Barcelona 08003, Spain 2 Department of Experimental and Health Sciences, Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), 08003 Barcelona, Spain 3ICREA, Pg. Lluís Companys 23, 08010 Barcelona, Spain ABSTRACT Fungi are a highly diverse group of heterotrophic eukaryotes characterized by the absence of phagotrophy and the presence of a chitinous cell wall. While unicellular fungi are far from rare, part of the evolutionary success of the group resides in their ability to grow indefinitely as a cylindrical multinucleated cell (hypha). Armed with these morphological traits and with an extremely high metabolical diversity, fungi have conquered numerous ecological niches and have shaped a whole world of interactions with other living organisms. Herein we survey the main evolutionary and ecological processes that have guided fungal diversity. We will first review the ecology and evolution of the zoosporic lineages and the process of terrestrialization, as one of the major evolutionary transitions in this kingdom. Several plausible scenarios have been proposed for fungal terrestralization and we here propose a new scenario, which considers icy environments as a transitory niche between water and emerged land. We then focus on exploring the main ecological relationships of Fungi with other organisms (other fungi, protozoans, animals and plants), as well as the origin of adaptations to certain specialized ecological niches within the group (lichens, black fungi and yeasts). -

Fungal Planet Description Sheets: 716–784 By: P.W

Fungal Planet description sheets: 716–784 By: P.W. Crous, M.J. Wingfield, T.I. Burgess, G.E.St.J. Hardy, J. Gené, J. Guarro, I.G. Baseia, D. García, L.F.P. Gusmão, C.M. Souza-Motta, R. Thangavel, S. Adamčík, A. Barili, C.W. Barnes, J.D.P. Bezerra, J.J. Bordallo, J.F. Cano-Lira, R.J.V. de Oliveira, E. Ercole, V. Hubka, I. Iturrieta-González, A. Kubátová, M.P. Martín, P.-A. Moreau, A. Morte, M.E. Ordoñez, A. Rodríguez, A.M. Stchigel, A. Vizzini, J. Abdollahzadeh, V.P. Abreu, K. Adamčíková, G.M.R. Albuquerque, A.V. Alexandrova, E. Álvarez Duarte, C. Armstrong-Cho, S. Banniza, R.N. Barbosa, J.-M. Bellanger, J.L. Bezerra, T.S. Cabral, M. Caboň, E. Caicedo, T. Cantillo, A.J. Carnegie, L.T. Carmo, R.F. Castañeda-Ruiz, C.R. Clement, A. Čmoková, L.B. Conceição, R.H.S.F. Cruz, U. Damm, B.D.B. da Silva, G.A. da Silva, R.M.F. da Silva, A.L.C.M. de A. Santiago, L.F. de Oliveira, C.A.F. de Souza, F. Déniel, B. Dima, G. Dong, J. Edwards, C.R. Félix, J. Fournier, T.B. Gibertoni, K. Hosaka, T. Iturriaga, M. Jadan, J.-L. Jany, Ž. Jurjević, M. Kolařík, I. Kušan, M.F. Landell, T.R. Leite Cordeiro, D.X. Lima, M. Loizides, S. Luo, A.R. Machado, H. Madrid, O.M.C. Magalhães, P. Marinho, N. Matočec, A. Mešić, A.N. Miller, O.V. Morozova, R.P. Neves, K. Nonaka, A. Nováková, N.H. -

The Flora Mycologica Iberica Project Fungi Occurrence Dataset

A peer-reviewed open-access journal MycoKeys 15: 59–72 (2016)The Flora Mycologica Iberica Project fungi occurrence dataset 59 doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.15.9765 DATA PAPER MycoKeys http://mycokeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research The Flora Mycologica Iberica Project fungi occurrence dataset Francisco Pando1, Margarita Dueñas1, Carlos Lado1, María Teresa Telleria1 1 Real Jardín Botánico-CSIC, Claudio Moyano 1, 28014, Madrid, Spain Corresponding author: Francisco Pando ([email protected]) Academic editor: C. Gueidan | Received 5 July 2016 | Accepted 25 August 2016 | Published 13 September 2016 Citation: Pando F, Dueñas M, Lado C, Telleria MT (2016) The Flora Mycologica Iberica Project fungi occurrence dataset. MycoKeys 15: 59–72. doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.15.9765 Resource citation: Pando F, Dueñas M, Lado C, Telleria MT (2016) Flora Mycologica Iberica Project fungi occurrence dataset. v1.18. Real Jardín Botánico (CSIC). Dataset/Occurrence. http://www.gbif.es/ipt/resource?r=floramicologicaiberi ca&v=1.18, http://doi.org/10.15468/sssx1e Abstract The dataset contains detailed distribution information on several fungal groups. The information has been revised, and in many times compiled, by expert mycologist(s) working on the monographs for the Flora Mycologica Iberica Project (FMI). Records comprise both collection and observational data, obtained from a variety of sources including field work, herbaria, and the literature. The dataset contains 59,235 records, of which 21,393 are georeferenced. These correspond to 2,445 species, grouped in 18 classes. The geographical scope of the dataset is Iberian Peninsula (Continental Portugal and Spain, and Andorra) and Balearic Islands. The complete dataset is available in Darwin Core Archive format via the Global Biodi- versity Information Facility (GBIF). -

Mitochondrial Evolution in the Entomopathogenic Fungal Genus Beauveria

Received: 29 September 2020 | Revised: 12 October 2020 | Accepted: 13 October 2020 DOI: 10.1002/arch.21754 RESEARCH ARTICLE Mitochondrial evolution in the entomopathogenic fungal genus Beauveria Travis Glare1 | Matt Campbell2 | Patrick Biggs2 | David Winter2 | Abigail Durrant1 | Aimee McKinnon1 | Murray Cox2 1Bio‐Protection Research Centre, Lincoln University, Lincoln, New Zealand Abstract 2 School of Fundamental Sciences, Massey Species in the fungal genus Beauveria are pathogens of University, Palmerston North, New Zealand invertebrates and have been commonly used as the ac- Correspondence tive agent in biopesticides. After many decades with few Glare Travis, Bio‐Protection Research Centre, Lincoln University, PO Box 85084, Lincoln species described, recent molecular approaches to clas- 7647, New Zealand. sification have led to over 25 species now delimited. Email: [email protected] Little attention has been given to the mitochondrial genomes of Beauveria but better understanding may led to insights into the nature of species and evolution in this important genus. In this study, we sequenced the mi- tochondrial genomes of four new strains belonging to Beauveria bassiana, Beauveria caledonica and Beauveria malawiensis, and compared them to existing mitochon- drial sequences of related fungi. The mitochondrial gen- omes of Beauveria ranged widely from 28,806 to 44,135 base pairs, with intron insertions accounting for most size variation and up to 39% (B. malawiensis) of the mi- tochondrial length due to introns in genes. Gene order of the common mitochondrial genes did not vary among the Beauveria sequences, but variation was observed in the number of transfer ribonucleic acid genes. Although phylogenetic analysis using whole mitochondrial gen- omes showed, unsurprisingly, that B. -

Septal Pore Caps in Basidiomycetes Composition and Ultrastructure

Septal Pore Caps in Basidiomycetes Composition and Ultrastructure Septal Pore Caps in Basidiomycetes Composition and Ultrastructure Septumporie-kappen in Basidiomyceten Samenstelling en Ultrastructuur (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. J.C. Stoof, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 17 december 2007 des middags te 16.15 uur door Kenneth Gregory Anthony van Driel geboren op 31 oktober 1975 te Terneuzen Promotoren: Prof. dr. A.J. Verkleij Prof. dr. H.A.B. Wösten Co-promotoren: Dr. T. Boekhout Dr. W.H. Müller voor mijn ouders Cover design by Danny Nooren. Scanning electron micrographs of septal pore caps of Rhizoctonia solani made by Wally Müller. Printed at Ponsen & Looijen b.v., Wageningen, The Netherlands. ISBN 978-90-6464-191-6 CONTENTS Chapter 1 General Introduction 9 Chapter 2 Septal Pore Complex Morphology in the Agaricomycotina 27 (Basidiomycota) with Emphasis on the Cantharellales and Hymenochaetales Chapter 3 Laser Microdissection of Fungal Septa as Visualized by 63 Scanning Electron Microscopy Chapter 4 Enrichment of Perforate Septal Pore Caps from the 79 Basidiomycetous Fungus Rhizoctonia solani by Combined Use of French Press, Isopycnic Centrifugation, and Triton X-100 Chapter 5 SPC18, a Novel Septal Pore Cap Protein of Rhizoctonia 95 solani Residing in Septal Pore Caps and Pore-plugs Chapter 6 Summary and General Discussion 113 Samenvatting 123 Nawoord 129 List of Publications 131 Curriculum vitae 133 Chapter 1 General Introduction Kenneth G.A. van Driel*, Arend F. -

Population Biology of Switchgrass Rust

POPULATION BIOLOGY OF SWITCHGRASS RUST (Puccinia emaculata Schw.) By GABRIELA KARINA ORQUERA DELGADO Bachelor of Science in Biotechnology Escuela Politécnica del Ejército (ESPE) Quito, Ecuador 2011 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE July, 2014 POPULATION BIOLOGY OF SWITCHGRASS RUST (Puccinia emaculata Schw.) Thesis Approved: Dr. Stephen Marek Thesis Adviser Dr. Carla Garzon Dr. Robert M. Hunger ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For their guidance and support, I express sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Marek, who has supported thought my thesis with his patience and knowledge whilst allowing me the room to work in my own way. One simply could not wish for a better or friendlier supervisor. I give special thanks to M.S. Maxwell Gilley (Mississippi State University), Dr. Bing Yang (Iowa State University), Arvid Boe (South Dakota State University) and Dr. Bingyu Zhao (Virginia State), for providing switchgrass rust samples used in this study and M.S. Andrea Payne, for her assistance during my writing process. I would like to recognize Patricia Garrido and Francisco Flores for their guidance, assistance, and friendship. To my family and friends for being always the support and energy I needed to follow my dreams. iii Acknowledgements reflect the views of the author and are not endorsed by committee members or Oklahoma State University. Name: GABRIELA KARINA ORQUERA DELGADO Date of Degree: JULY, 2014 Title of Study: POPULATION BIOLOGY OF SWITCHGRASS RUST (Puccinia emaculata Schw.) Major Field: ENTOMOLOGY AND PLANT PATHOLOGY Abstract: Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) is a perennial warm season grass native to a large portion of North America. -

A Higher-Level Phylogenetic Classification of the Fungi

mycological research 111 (2007) 509–547 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mycres A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi David S. HIBBETTa,*, Manfred BINDERa, Joseph F. BISCHOFFb, Meredith BLACKWELLc, Paul F. CANNONd, Ove E. ERIKSSONe, Sabine HUHNDORFf, Timothy JAMESg, Paul M. KIRKd, Robert LU¨ CKINGf, H. THORSTEN LUMBSCHf, Franc¸ois LUTZONIg, P. Brandon MATHENYa, David J. MCLAUGHLINh, Martha J. POWELLi, Scott REDHEAD j, Conrad L. SCHOCHk, Joseph W. SPATAFORAk, Joost A. STALPERSl, Rytas VILGALYSg, M. Catherine AIMEm, Andre´ APTROOTn, Robert BAUERo, Dominik BEGEROWp, Gerald L. BENNYq, Lisa A. CASTLEBURYm, Pedro W. CROUSl, Yu-Cheng DAIr, Walter GAMSl, David M. GEISERs, Gareth W. GRIFFITHt,Ce´cile GUEIDANg, David L. HAWKSWORTHu, Geir HESTMARKv, Kentaro HOSAKAw, Richard A. HUMBERx, Kevin D. HYDEy, Joseph E. IRONSIDEt, Urmas KO˜ LJALGz, Cletus P. KURTZMANaa, Karl-Henrik LARSSONab, Robert LICHTWARDTac, Joyce LONGCOREad, Jolanta MIA˛ DLIKOWSKAg, Andrew MILLERae, Jean-Marc MONCALVOaf, Sharon MOZLEY-STANDRIDGEag, Franz OBERWINKLERo, Erast PARMASTOah, Vale´rie REEBg, Jack D. ROGERSai, Claude ROUXaj, Leif RYVARDENak, Jose´ Paulo SAMPAIOal, Arthur SCHU¨ ßLERam, Junta SUGIYAMAan, R. Greg THORNao, Leif TIBELLap, Wendy A. UNTEREINERaq, Christopher WALKERar, Zheng WANGa, Alex WEIRas, Michael WEISSo, Merlin M. WHITEat, Katarina WINKAe, Yi-Jian YAOau, Ning ZHANGav aBiology Department, Clark University, Worcester, MA 01610, USA bNational Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information, -

Fungi Fundamentals What Is Biology? What Is Life? Seven Common Components to All Life Forms

Fungi Fundamentals What is Biology? What is life? Seven common components to all life forms. What are fungi? How do fungi compare to other organisms on the tree of life? What are fungi? • Eukaryotic What are fungi? • Eukaryotic • Multicellular / Filamentous What are fungi? • Eukaryotic • Multicellular / Filamentous • Heterotrophic What are fungi? • Eukaryotic • Multicellular / Filamentous • Heterotrophic • Sessile/non-motile = “Vegetative” What are fungi? • Eukaryotic • Multicellular / Filamentous • Heterotrophic • Sessile/non-motile = “Vegetative” • Reproduce via spores (sexual & asexual) Kingdom Fungi • Eukaryotic • Multicellular / Filamentous • Heterotrophic • Sessile/non-motile = “Vegetative” • Reproduce via spores (sexual & asexual) Kingdom Fungi • Eukaryotic • Multicellular / Filamentous • Heterotrophic hyphae • Sessile/non-motile = “Vegetative” • Reproduce via spores (sexual & asexual) mycelium Kingdom Fungi Symbiotic Fungi • Eukaryotic • Multicellular / Filamentous • Heterotrophic • Sessile/non-motile = “Vegetative” • Reproduce via spores (sexual & asexual) Mycorrhizal mutualists Parasitic / Pathogenic Fungi Decay fungi “saprotrophic” Mycology: Laboratory Homework Fungi Are Everywhere! - Expose Malt Extract Agar Petri dishes to the environment of your home. Overnight. Anywhere you want. - Label plate and seal with parafilm. - Wait 3 days. - Record what grows on days 4-6. Bring back next week! Mycology: Laboratory Homework Fungi Are Everywhere! - Expose Malt Extract Agar Petri dishes to the environment of your home. Overnight. Anywhere you want. - Label plate and seal with parafilm. - Wait 3 days. - Record what grows on days 4-6. Bring back next week! Mycology: Laboratory Homework Growing Mushrooms! - Buy some mushrooms from the grocery store and bring them in next week so we can start growing them. Biological Diversity Species concepts Morphological species concept: species can be differentiated from each other by physical features. Not all mushrooms are alike. -

Identification of Culture-Negative Fungi in Blood and Respiratory Samples

IDENTIFICATION OF CULTURE-NEGATIVE FUNGI IN BLOOD AND RESPIRATORY SAMPLES Farida P. Sidiq A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2014 Committee: Scott O. Rogers, Advisor W. Robert Midden Graduate Faculty Representative George Bullerjahn Raymond Larsen Vipaporn Phuntumart © 2014 Farida P. Sidiq All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Scott O. Rogers, Advisor Fungi were identified as early as the 1800’s as potential human pathogens, and have since been shown as being capable of causing disease in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised people. Clinical diagnosis of fungal infections has largely relied upon traditional microbiological culture techniques and examination of positive cultures and histopathological specimens utilizing microscopy. The first has been shown to be highly insensitive and prone to result in frequent false negatives. This is complicated by atypical phenotypes and organisms that are morphologically indistinguishable in tissues. Delays in diagnosis of fungal infections and inaccurate identification of infectious organisms contribute to increased morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients who exhibit increased vulnerability to opportunistic infection by normally nonpathogenic fungi. In this study we have retrospectively examined one-hundred culture negative whole blood samples and one-hundred culture negative respiratory samples obtained from the clinical microbiology lab at the University of Michigan Hospital in Ann Arbor, MI. Samples were obtained from randomized, heterogeneous patient populations collected between 2005 and 2006. Specimens were tested utilizing cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction amplification of internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of ribosomal DNA utilizing panfungal ITS primers. -

V.Woolleythesisfinalversion Corrections VWJWSR

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/129924 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Elucidating the natural function of cordycepin, a secondary metabolite of the fungus Cordyceps militaris, and its potential as a novel biopesticide in Integrated Pest Management By Victoria Clare Woolley A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Life Sciences University of Warwick, School of Life Sciences September 2018 Table of Contents List of Figures ......................................................................................................... 1 List of Tables ........................................................................................................... 3 Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................. 6 Declarations ............................................................................................................ 7 Abstract .................................................................................................................. -

Reference Guide to the Classification of Fungi and Fungal-Like Protists, with Emphasis on the Fungal Genera with Medical Importance (Circa 2009)

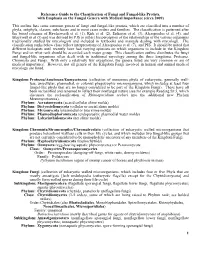

Reference Guide to the Classification of Fungi and Fungal-like Protists, with Emphasis on the Fungal Genera with Medical Importance (circa 2009) This outline lists some common genera of fungi and fungal-like protists, which are classified into a number of phyla, subphyla, classes, subclasses and in most cases orders and families. The classification is patterned after the broad schemes of Hawksworth et al. (1), Kirk et al. (2), Eriksson et al. (3), Alexopoulos et al. (4), and Blackwell et al (5) and was devised by PJS to reflect his perception of the relationships of the various organisms traditionally studied by mycologists and included in textbooks and manuals dealing with mycology. The classification ranks below class reflect interpretations of Alexopoulos et al. (7), and PJS. It should be noted that different biologists until recently have had varying opinions on which organisms to include in the Kingdom Fungi and on what rank should be accorded each major group. This classification outline distributes the fungi and fungal-like organisms often dealt with in traditional mycology among the three kingdoms, Protozoa, Chromista and Fungi. With only a relatively few exceptions, the genera listed are very common or are of medical importance. However, not all genera of the Kingdom Fungi involved in human and animal medical mycology are listed. Kingdom: Protozoa/Amebozoa/Eumycetozoa (collection of numerous phyla of eukaryotic, generally wall- less, unicellular, plasmodial, or colonial phagotrophic microorganisms, which includes at least four fungal-like phyla that are no longer considered to be part of the Kingdom Fungi). These have all been reclassified and renamed to reflect their nonfungal nature (see for example Reading Sz 5, which discusses the reclassification of Rhinosporidium seeberi into the additional new Phylum Mezomycetozoea). -

Student 3-Minute Oral Presentations--All.Pdf

Oklahoma NSF EPSCoR Bioenergy Research and Education Genomic Analysis of the Lignocellulotic Anaerobic Fungus Orpinomyces C1A MB Couger, Audra Liggenstoffer Mostafa Elshahed Oklahoma State University STUDENT #1 STUDENT #1 Objectives Efficient conversion of recalcitrant Non-Feed Stock biomass, such as switchgrass, currently is a major obstacle preventing the actualization of Bio-fuels as a widely used energy source. Identification of additional enzymes capable of lignocellulose degradation from relevant organisms would provide a greater toolset for bio-fuel production. Genomic Analysis of the lignocellolosic anaerobic fungal genus Neocallamastix could identify such enzymes. STUDENT #1 Methods STUDENT #1 Results Number In Assembly/Annotation Statistics Value GH C1A CAZy Group Substrate Specificities Total Reads 146 Million Pairs GH10 47 HemiCellulose Total Amounf of Bases 29.2GB GH11 44 HemiCellulose Total Assembled Bases 100MB GH5 38 Mixed Cellulose/HemiCellulose n50 1600bp GH43 36 HemiCellulose n90 520bp GH6 30 Cellulose GH48 26 Cellulose/Chitanse AT content Range 84-94% GH3 24 HemiCellulose At Content Average 87% GH13 21 Othe Sugar Mixed Total Amount of Bases 176 Million GH45 20 Cellulose Total Assembled Bases 35GB GH9 18 Cellulose/ Other Sugar mixed Transcripts Assemblies > 300BP 25935 GH31 17 Other Sugars Mixed Transcripts with BLASTX evalue < e-5 10449 GH16 12 Other Sugars Mixed Average Length of Blastx Transcripts 1075bp GH18 11 Other Sugars Mixed Number of Consensus Models 14564 Average Length of Model with top hit of e-5 or