The Problem of Identity in John Updike's Rabbit Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

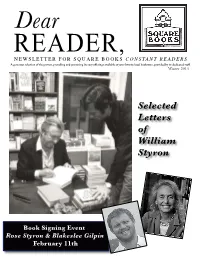

Selected Letters of William Styron

Dear Winter 2013 Selected Letters of William Styron Book Signing Event Rose Styron & Blakeslee Gilpin February 11th THE YEAR IN REVIEW 2012 With 2012 in rear view, we are very thankful for the many writers who came to us and the publishers who sent them to Square Books, as their books tend to dominate our bestseller list; some, like James Meek (The Heart Broke In, #30) and Lawrence Norfolk (John Saturnall’s Feast, #29), from as far as England – perhaps it’s the fascination with Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey (67) or J. K. Rowling’s Casual Vacancy (78). But as Dear Readers know, this list is usually crowded with those who live or have lived here, like Dean Wells’ Every Day by the Sun (22) or (long ago) James Meredith (A Mission From God, (10); William Faulkner’s Selected Stories (43), Ole Miss at Oxford, by Bill Morris (37), Mike Stewart’s Sporting Dogs and Retriever Training (39), John Brandon’s A Million Heavens (24), Airships (94), by Barry Hannah, Dream Cabinet by Ann Fisher-Wirth (87), Beginnings & Endings (85) by Ron Borne, Facing the Music (65) by Larry Brown, Neil White’s In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (35), the King twins’ Y’all Twins? (12), Tom Franklin’s Crooked Letter Crooked Letter (13), The Fall of the House of Zeus (15) by Curtis Wilkie, Julie Cantrell’s Into the Free (16), Ole Miss Daily Devotions (18), and two perennial local favorites Wyatt Waters’ Oxford Sketchbook (36) and Square Table (8), which has been in our top ten ever since it was published; not to forget Sam Haskell and Promises I Made My Mother (6) or John Grisham, secure in the top two spots with The Racketeer and Calico Joe, nor our friend Richard Ford, with his great novel, Canada (5). -

AP English Literature and Composition: Study Guide

AP English Literature and Composition: Study Guide AP is a registered trademark of the College Board, which was not involved in the production of, and does not endorse, this product. Key Exam Details While there is some degree of latitude for how your specific exam will be arranged, every AP English Literature and Composition exam will include three sections: • Short Fiction (45–50% of the total) • Poetry (35–45% of the total) • Long Fiction or Drama (15–20% of the total) The AP examination will take 3 hours: 1 hour for the multiple-choice section and 2 hours for the free response section, divided into three 40-minute sections. There are 55 multiple choice questions, which will count for 45% of your grade. The Free Response writing component, which will count for 55% of your grade, will require you to write essays on poetry, prose fiction, and literary argument. The Free Response (or “Essay” component) will take 2 hours, divided into the three sections of 40 minutes per section. The course skills tested on your exam will require an assessment and explanation of the following: • The function of character: 15–20 % of the questions • The psychological condition of the narrator or speaker: 20–25% • The design of the plot or narrative structure: 15–20% • The employment of a distinctive language, as it affects imagery, symbols, and other linguistic signatures: 10–15% • And encompassing all of these skills, an ability to draw a comparison between works, authors and genres: 10–15 % The free response portion of the exam will test all these skills, while asking for a thesis statement supported by an argument that is substantiated by evidence and a logical arrangement of the salient points. -

University of Alberta of Primary & Secondary Materials, I948-2007

267 Books in Review I Comptes rendus photographs of first editions. Many of them are luscious and highly evocative, soft-core pornography for bibliophiles to which I am not immune even though I have no special interest in dust jackets of the 1930s and 40s. And in fact I will be quite happy to have a copy of this book in my library, just as I would a picture-book of vintage baseball cards or comic books unaccompanied by very much in the way of analytical text. As eye-candy it is great; as a work of scholarly interest, not so much. WILLIAM BEARD University ofAlberta Jack De Bellis and Michael Broomfield. john Updike: A Bibliography ofPrimary & Secondary Materials, I948-2007. New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2007. 624 pp.; US $195.00 ISBN 9781584561958 John Updike's prolificacy is no secret. In addition to nearly sixty books issued by Knopf, he has published scores oflimited editions and broadsides, and his stories, poems, essays, speeches and reviews have appeared in hundreds of periodicals. When I last visited Harvard's Houghton Library, where his papers are stored, the librarian told me that Updike's collection of personal papers was among that library's largest. Although no surprise, keep in mind that the Houghton holds the papers of many major figures in American literature and history. Funher, in the twelve years since that visit, Updike has undoubtedly deposited dozens of additional cartons filled with books, manuscripts, notes, diagrams and correspondence, increasing the size of his collection considerably. Given this unusually abundant creative outpouring, the task of keeping up with Updike's oeuvre is nearly a full-time job requiring a thoroughly dedicated bibliographer. -

(For an Exceptional Debut Novel, Set in the South) Names Final Four

FOR RELEASE NOVEMBER 20 FIRST ANNUAL CROOK’S CORNER BOOK PRIZE (FOR AN EXCEPTIONAL DEBUT NOVEL, SET IN THE SOUTH) NAMES FINAL FOUR The linkages between good writing and good food and drink are clear and persistent. I can’t imagine a better means of celebrating their entwining than this innovative award. — John T. Edge CHAPEL HILL, NC – The Crook’s Corner Book Prize announced four finalists for the first annual Crook’s Corner Book Prize, to be awarded for an exceptional debut novel set in the American South. The winner will be announced January 6th. The four finalists are LEAVING TUSCALOOSA, by Walter Bennett (Fuze Publishing); CODE OF THE FOREST, by Jon Buchan (Joggling Board Press); A LAND MORE KIND THAN HOME, by Wiley Cash (William Morrow); and THE ENCHANTED LIFE OF ADAM HOPE, by Rhonda Riley (Ecco). “It was exciting to find so many great books—several of them from independent publishers (even micro-publishers)—emerging from our reading,” said Anna Hayes, founder and president of the Crook’s Corner Book Prize Foundation. “This grassroots effort to discover and champion books in general, Southern Literature in particular, is amazing and refreshing,” said Jamie Fiocco, owner of Flyleaf Books and president of the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance. “The Crook’s Corner Book Prize is a great example of what independent booksellers have been doing for years: finding top- quality reading experiences, regardless of the book’s origin—small or large publisher. Readers trust the rich literary history of the South to deliver a sense of place and great characters; now this Prize lets readers learn about the cream of the crop of new storytellers.” Intended to encourage emerging writers in a publishing environment that seems to change daily, the Prize is equally open to self-published authors and traditionally published authors. -

Women and Evil in Contemporary American Novels"

DOI: https://doi.org/10.22201/ffyl.01860526p.1990.4.954 The Sterile or Life-Denying Society: Women and Evil in Contemporary American Novels" Society is a joint-stock company, in which the members agree, for the beller securing ofhis bread to each share-holder, to surrender the librrty and culture of the eater. The virtue in most request is confonnity. Self-reliance is its aversion ... Whoso would be aman, must be a nonconfonnist. by Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Self-Reliance" . Charles MASINTON Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 1 At first glance, it might appear that contemporary American novelists have largely turned away from the age-old problem of evil to concern themselves with purely esthetic matters 01' with issues relating to a technological, urban, post-Christian society, an "enlightened" society in which what used to be understood as evil can be accounted for in psychological, sociological, political, 01' scientific terms. But this is not the case. While some of our serious, critically celebrated novelists since the end ofWorld War II - John Barth, Roben Coover, William H. Gass, and Vladimir Nabokov come to mind- have dedicated themselves principally to the formal and technical aspects of their craft, an imposing number of contemporary novelists recognize the reality of evil in human affairs and represent it in a wide variety of ways. In contrast to those writers named aboye, for whom novels are primarily objects of beauty and delight and not vehicles for com municating social 01' philosophical insights, most important American novelists still address the pressing issues of day-to-day existence, including the problem of evil. -

Chinese Scholars' Perspective on John Updike's "Rabbit Tetralogy"1

Linguistics and Literature Studies 8(1): 8-13, 2020 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2020.080102 Chinese Scholars' Perspective on John Updike's 1 "Rabbit Tetralogy" Zhao Cheng Foreign Languages Studies School, Soochow University, China Received Ocotber 15, 2019; Revised November 25, 2019; Accepted December 4, 2019 Copyright©2020 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract Updike's masterpiece, using skillful realism, most productive, and most awarded writers in the United succeeded in drawing a panoramic picture of the American States in the second half of the twentieth century. "Rabbit society from the 1950s to the early 1990s in the "Rabbit Tetralogy", Updike’s masterpiece, the core of the entire Tetralogy." Updike strives to reflect the changes in literary creation system of Updike, composed of "Rabbit contemporary American social culture for nearly half a Run" (1960), "Rabbit Redux" (1971), "Rabbit is Rich" century from the "rabbit" Harry, the everyman of the (1981), and "Rabbit at Rest" (1991), represents the highest American society and the life experiences of his ordinary achievement of the writer’s novel creation. In famil y. "Rabbit Tetralogy" truly reflects the living contemporary American literature, the publication of conditions of the contradictions of contemporary Rabbit Tetralogy is considered as a landmark event, and Americans: endless pursuit of free life or independent self Updike’s character "Rabbit" Harry, one of the "most and the embarrassment and helplessness of it; the confusing literary figures in traditional American customary life and hedonism under the traditional values, literature", has become a classic figure in contemporary the intense collision of self-indulgent lifestyles inspired by American literature. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Books and Coffee Past Presenters

Books and Coffee Past Presenters Year Speaker Author Title 1951 William Braswell Hemingway Across the River and Into the Trees Chester Eisinger Miller Death of a Salesman Paul Fatout -- “Mark Twain” Robert Lowe Pound Letters Barriss Mills Faulkner Collected Stories Herbert Muller Niebuhr Faith in History Albert Rolfs Fatout Ambrose Bierce Louise Rorabacher Orwell Animal Farm Emerson Sutcliffe Kent Declensions in the Air 1952 Welsey Carroll Boswell London Journal Richard Voorhees Greene The Power and the Glory Richard Cordell Irvine The Universe of George Bernard Shaw Harold Watts Mann The Holy Sinner Roy Curtis Hall Leave Your Language Alone! Richard Greene Altick The Scholar Adventurers R. W. Babcock -- “On Reading Shakespeare” Richard Crowder Williams Later Collected Poems 1953 Herbert Muller Ceram Gods, Graves, and Scholars William Hastings Wouk The Cain Mutiny J. H. McKee Ferril I Hate Thursday Arthur Koenig Dostoievsky The Diary of a Writer George Schick Boswell Boswell in Holland Darrel Abel Steinbeck East of Eden H. B. Knoll Walton The Compleat Angler Raymond Himelick Cabell Quiet Please 1954 Paul Fatout Boswell Boswell on the Grand Tour George S. Wykoff Bonavia-Hunt Pemberley Shades Lewis Freed Eliot The Cocktail Party R. M. Bertram Cary The Horse's Mouth Laird Bell Smith Man and His Gods Bernard Schmidt Michener The Bridges at Toki-Ri Victor Gibbens Randolf & Wilson Down in the Holler William Braswell Thurber Thurber Country 1955 Richard Cordell Larson An American in Europe Arnold Drew Jarrell Pictures from an Institution Russell Cosper Kafka The Castle M. W. Tillson Ives Tales of America Maurice Beebe Faulkner A Fable Walter Maneikis Algren The Man with the Golden Arm Virgil Lokke West The Day of the Locusts Robert Ogle White The Second Tree from the Corner 1956 Lewis Freed Alberto Moravia A Ghost at Noon R.W. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Rabbit Run by John Updike Rabbit Run by John Updike

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Rabbit Run by John Updike Rabbit Run by John Updike. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 6588763ffc5c0d52 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Rabbit Run by John Updike. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 65887640090515f4 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. -

Suburbs in American Literature

FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA UNIVERZITY PALACKÉHO KATEDRA ANGLISTIKY A AMERIKANISTIKY SUBURBS IN AMERICAN LITERATURE A STUDY OF THREE SELECTED SUBURBAN NOVELS (Bakalářská práce) Autor: Lucie Růžičková Anglická filologie- Žurnalistika Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, PhD. OLOMOUC 2013 Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Suburbs in American Literature A Study of Three Selected Suburban Novels (Diplomová práce) Autor: Lucie Růžičková Studijní obor: Anglická a žurnalistika Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D. Počet stran (podle čísel): Počet znaků: Olomouc 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně a uvedla úplný seznam citované a použité literatury. V Olomouci dne 25.4. 2013 ………………………… I would like to say thank you to Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D., who has been very patient with me and has been of a great support and help while supervising my thesis. TABLE OF CONTENTS: 1. Introduction ………………………………………………………. 3 2. Suburbs – The Terminology ……………………………………… 5 2.1 American Suburbs ……………………………………………. 5 2.2 Brief history of American suburbia …………………………... 6 2.3 Suburban novel and well-know authors ……………………… 7 3. John Updike ………………………………………………………. 10 3.1 Biography ……………………………………………………... 10 3.2 Bibliography …………………………………………………... 11 4. Rabbit, Run – The Analysis ………………………………………. 13 4.1 The plot ……………………………………………………….. 13 4.2 The portrait of suburb ………………………………………… 16 4.3 Characters and their relationships …………………………….. 17 4.3.1 Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom ……………………………….. 17 4.3.2 Janice Angstrom …………………………………………. 18 4.3.3 Ruth Leonard …………………………………………….. 19 5. Richard Ford ……………………………………………………….. 21 5.1 Biography ……………………………………………………… 21 5.2 Bibliography …………………………………………………… 22 6. The Sportswriter - The Analysis …………………………………… 24 6.1 The plot ………………………………………………………… 24 6.2 The portrait of suburb ………………………………………….. 27 6.3 Characters and their relationships ……………………………… 28 6.3.1 Frank Bascombe …………………………………………. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

Philip Roth Biography Appeared Before the Book Came Out, with Major Stories in Magazines and Literary Publications

Sexual Assault Allegations Against Biographer Halt Shipping of His Roth Book W.W. Norton, citing the accusations that the author, Blake Bailey, faces, said it would stop shipping and promoting his new best-selling book. “Philip Roth: The Biography” went on sale earlier this month.Credit...W.W. Norton, via Associated Press By Alexandra Alter and Rachel Abrams Published April 21, 2021Updated May 17, 2021 Earlier this month, the biographer Blake Bailey was approaching what seemed like the apex of his literary career. Reviews of his highly anticipated Philip Roth biography appeared before the book came out, with major stories in magazines and literary publications. It landed on the New York Times best-seller list this week. Now, allegations against Mr. Bailey, 57, have emerged, including claims that he sexually assaulted two women, one as recently as 2015, and that he behaved inappropriately toward middle school students when he was a teacher in the 1990s. His publisher, W.W. Norton, took swift and unusual action: It said on Wednesday that it had stopped shipments and promotion of his book. “These allegations are serious,” it said in a statement. “In light of them, we have decided to pause the shipping and promotion of ‘Philip Roth: The Biography’ pending any further information that may emerge.” Norton, which initially printed 50,000 copies of the title, has stopped a 10,000-copy second printing that was scheduled to arrive in early May. It has also halted advertising and media outreach, and events that Norton arranged to promote the book are being canceled. The pullback from the publisher came just days after Mr.