Women and Evil in Contemporary American Novels"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

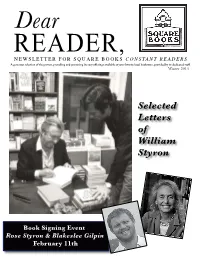

Selected Letters of William Styron

Dear Winter 2013 Selected Letters of William Styron Book Signing Event Rose Styron & Blakeslee Gilpin February 11th THE YEAR IN REVIEW 2012 With 2012 in rear view, we are very thankful for the many writers who came to us and the publishers who sent them to Square Books, as their books tend to dominate our bestseller list; some, like James Meek (The Heart Broke In, #30) and Lawrence Norfolk (John Saturnall’s Feast, #29), from as far as England – perhaps it’s the fascination with Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey (67) or J. K. Rowling’s Casual Vacancy (78). But as Dear Readers know, this list is usually crowded with those who live or have lived here, like Dean Wells’ Every Day by the Sun (22) or (long ago) James Meredith (A Mission From God, (10); William Faulkner’s Selected Stories (43), Ole Miss at Oxford, by Bill Morris (37), Mike Stewart’s Sporting Dogs and Retriever Training (39), John Brandon’s A Million Heavens (24), Airships (94), by Barry Hannah, Dream Cabinet by Ann Fisher-Wirth (87), Beginnings & Endings (85) by Ron Borne, Facing the Music (65) by Larry Brown, Neil White’s In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (35), the King twins’ Y’all Twins? (12), Tom Franklin’s Crooked Letter Crooked Letter (13), The Fall of the House of Zeus (15) by Curtis Wilkie, Julie Cantrell’s Into the Free (16), Ole Miss Daily Devotions (18), and two perennial local favorites Wyatt Waters’ Oxford Sketchbook (36) and Square Table (8), which has been in our top ten ever since it was published; not to forget Sam Haskell and Promises I Made My Mother (6) or John Grisham, secure in the top two spots with The Racketeer and Calico Joe, nor our friend Richard Ford, with his great novel, Canada (5). -

(For an Exceptional Debut Novel, Set in the South) Names Final Four

FOR RELEASE NOVEMBER 20 FIRST ANNUAL CROOK’S CORNER BOOK PRIZE (FOR AN EXCEPTIONAL DEBUT NOVEL, SET IN THE SOUTH) NAMES FINAL FOUR The linkages between good writing and good food and drink are clear and persistent. I can’t imagine a better means of celebrating their entwining than this innovative award. — John T. Edge CHAPEL HILL, NC – The Crook’s Corner Book Prize announced four finalists for the first annual Crook’s Corner Book Prize, to be awarded for an exceptional debut novel set in the American South. The winner will be announced January 6th. The four finalists are LEAVING TUSCALOOSA, by Walter Bennett (Fuze Publishing); CODE OF THE FOREST, by Jon Buchan (Joggling Board Press); A LAND MORE KIND THAN HOME, by Wiley Cash (William Morrow); and THE ENCHANTED LIFE OF ADAM HOPE, by Rhonda Riley (Ecco). “It was exciting to find so many great books—several of them from independent publishers (even micro-publishers)—emerging from our reading,” said Anna Hayes, founder and president of the Crook’s Corner Book Prize Foundation. “This grassroots effort to discover and champion books in general, Southern Literature in particular, is amazing and refreshing,” said Jamie Fiocco, owner of Flyleaf Books and president of the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance. “The Crook’s Corner Book Prize is a great example of what independent booksellers have been doing for years: finding top- quality reading experiences, regardless of the book’s origin—small or large publisher. Readers trust the rich literary history of the South to deliver a sense of place and great characters; now this Prize lets readers learn about the cream of the crop of new storytellers.” Intended to encourage emerging writers in a publishing environment that seems to change daily, the Prize is equally open to self-published authors and traditionally published authors. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

Alice Walker Papers, Circa 1930-2014

WALKER, ALICE, 1944- Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Digital Material Available in this Collection Descriptive Summary Creator: Walker, Alice, 1944- Title: Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1061 Extent: 138 linear feet (253 boxes), 9 oversized papers boxes and 1 oversized papers folder (OP), 10 bound volumes (BV), 5 oversized bound volumes (OBV), 2 extraoversized papers folders (XOP) 2 framed items (FR), AV Masters: 5.5 linear feet (6 boxes and CLP), and 7.2 GB of born digital materials (3,054 files) Abstract: Papers of Alice Walker, an African American poet, novelist, and activist, including correspondence, manuscript and typescript writings, writings by other authors, subject files, printed material, publishing files and appearance files, audiovisual materials, photographs, scrapbooks, personal files journals, and born digital materials. Language: Materials mostly in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Selected correspondence in Series 1; business files (Subseries 4.2); journals (Series 10); legal files (Subseries 12.2), property files (Subseries 12.3), and financial records (Subseries 12.4) are closed during Alice Walker's lifetime or October 1, 2027, whichever is later. Series 13: Access to processed born digital materials is only available in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (the Rose Library). Use of the original digital media is restricted. The same restrictions listed above apply to born digital materials. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. -

The Literary Heroes of Fitzgerald and Hemingway ; Updike and Bellow Martha Ristine Skyrms Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1979 The literary heroes of Fitzgerald and Hemingway ; Updike and Bellow Martha Ristine Skyrms Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Skyrms, Martha Ristine, "The literary heroes of Fitzgerald and Hemingway ; Updike and Bellow " (1979). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 6966. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/6966 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The literary heroes of Fitzgerald and Hemingway; Updike and Bellow by Martha Ristine Skyrms A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English Approved: Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1979 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 The Decades 1 FITZGERALD g The Fitzgerald Hero 9 g The Fitzgerald Hero: Summary 27 ^ HEMINGWAY 29 . The Hemingway Hero 31 ^ The Hemingway Hero; Summary 43 THE HERO OF THE TWENTIES 45 UPDIKE 47 The Updike Hero 43 The Updike Hero: Summary 67 BELLOW 70 The Bellow Hero 71 The Bellow Hero: Summary 9I THE HERO OF THE SIXTIES 93 ir CONCLUSION 95 notes , 99 Introduction 99 Fitzgerald 99 Hemingway j_Oi The Hero of the Twenties loi Updike 1Q2 Bellow BIBLIOGRAPHY 104 INTRODUCTION 9 This thesis will undertake an examination of the literary heroes of the nineteen-twenties and the nineteen-sixties, emphasizing the qualities which those heroes share and those qualities which distinguish them. -

László Dányi the Eccentric Against the Mainstream

LÁSZLÓ DÁNYI THE ECCENTRIC AGAINST THE MAINSTREAM: WILLIAM STYRON, 75 William Styron (1925- ) has simultaneously been considered as one of the most controversial and the most admired authors in the United States. He has always resisted swimming with the current of postmodernism, and even during the heydays of that ephemeral mode of writing he achieved unprecedented recognition by the reading public. Styron will celebrate his 75th birthday in 2000, and the coincidence of the two significant figures instantly invites the question of appreciation. The latest approach to Styron's work and life, has been provided by James L. West III, who meticulously explored the multitude of dimensions that reveal the meaning and significance of Styron's art. So the unavoidable questions are: what comprises the Styron legacy for the generations of the 21st century, and what is the definition of the author's place, and what is his contribution to American literature? In the search for the answers to the questions, first, I will identify the major thematic patterns in Styron's works, then I will summarize major critical approaches to his. oeuvre and explore the Faulknerian heritage in his novels. What are the social icons that can be traced in Styron's works, and what are the major thematic patterns that constitute his novels? The first of the novels is his poetically written Lie Down in Darkness (1951) which portrays a Southern family crumbling into bits in the shadow of the mixed Southern ethical inheritance. The characters who act out the tragedy of this family are Peyton Loftis, the daughter, whose suicide commences the meditation over the estrange- 9 ment of the family members from one another; Helen Loftis, the pious mother, who wastes all her love over her crippled daughter, Maudie; and Milton Loftis, the weak and alcoholic father adoring his daughter, Peyton. -

Award Winning Books

More Man Booker winners: 1995: Sabbath’s Theater by Philip Roth Man Booker Prize 1990: Possession by A. S. Byatt 1994: A Frolic of His Own 1989: Remains of the Day by William Gaddis 2017: Lincoln in the Bardo by Kazuo Ishiguro 1993: The Shipping News by Annie Proulx by George Saunders 1985: The Bone People by Keri Hulme 1992: All the Pretty Horses 2016: The Sellout by Paul Beatty 1984: Hotel du Lac by Anita Brookner by Cormac McCarthy 2015: A Brief History of Seven Killings 1982: Schindler’s List by Thomas Keneally 1991: Mating by Norman Rush by Marlon James 1981: Midnight’s Children 1990: Middle Passage by Charles Johnson 2014: The Narrow Road to the Deep by Salman Rushdie More National Book winners: North by Richard Flanagan 1985: White Noise by Don DeLillo 2013: Luminaries by Eleanor Catton 1983: The Color Purple by Alice Walker 2012: Bring Up the Bodies by Hilary Mantel 1982: Rabbit Is Rich by John Updike 2011: The Sense of an Ending National Book Award 1980: Sophie’s Choice by William Styron by Julian Barnes 1974: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon 2010: The Finkler Question 2016: Underground Railroad by Howard Jacobson by Colson Whitehead 2009: Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel 2015: Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson 2008: The White Tiger by Aravind Adiga 2014: Redeployment by Phil Klay 2007: The Gathering by Anne Enright 2013: Good Lord Bird by James McBride National Book Critics 2006: The Inheritance of Loss 2012: Round House by Louise Erdrich by Kiran Desai 2011: Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward Circle Award 2005: The Sea by John Banville 2010: Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon 2004: The Line of Beauty 2009: Let the Great World Spin 2016: LaRose by Louise Erdrich by Alan Hollinghurst by Colum McCann 2015: The Sellout by Paul Beatty 2003: Vernon God Little by D.B.C. -

Non-Standard English Varieties in Literary Translation: the Help by Kathryn Stockett

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English-Language Translation Bc. Petra Sládková Non-Standard English Varieties in Literary Translation: The Help by Kathryn Stockett Master‘s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Renata Kamenická, Ph. D. 2013 1 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author‘s signature 2 I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. Renata Kamenická, Ph.D., for her thorough feedback and valuable advice. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 2. (Non)Standard American English .......................................................................... 9 2.1. African American Vernacular English ............................................................. 11 2.2. American White Southern English ................................................................... 13 3. Translation of Cultural Items ............................................................................... 16 4. Theoretical Approaches to Translating Dialects ................................................ 18 4.1. Basic Notions on Equivalence in Translation .................................................. 18 4.2. Translating Style .............................................................................................. 20 4.2.1. Basis for Stylistic Analysis of Fiction ..................................................... -

The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter

Related Non-Fiction THE HEART IS A [ The Lonely Hunter: a Biography of Carson McCullers by Virginia LONELY HUNTER Spencer Carr Suggestions for Further Reading [ The Republic of Imagination: American in Three Books by Azar Nafisi [ February House by Sherrill Tippins “The most fatal thing a man can do is try to stand alone.” [ Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love by Myron Uhlberg Other Works by Carson McCullers [ A Loss for Words: the Story of Deafness in a Family by Lou Ann [ Reflections in a Golden Eye (1941) Walker [ The Member of The Wedding (1946) [ Train Go Sorry: Inside a Deaf World by Leah Hager Cohen [ Ballad of the Sad Café and Other Stories (1951) [ Clock Without Hands (1961) [ Irrepressible: The Jazz Age Life of Henrietta Bingham by Emily [ The Mortgaged Heart a posthumous collection (1971) Bingham [ The Queer South: LGBTQ Writers on the American South ed. Douglas Ray McCullers’ The Modern South Contemporaries [ Black Man in a White Coat: a Doctor's Reflections on Race and Medicine by Damon Tweedy, M.D. [ The Long Home by William Gay Paul Bowles Truman Capote [ Ellen Foster by Kaye Gibbons [ South Toward Home: Travels in Southern Literature by Margaret Eby Flannery O’Connor [ Knockemstiff by Donald Ray Pollock Walker Percy Eudora Welty [ Swamplandia by Karen Russell [ Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression Richard Wright by Morris Dickstein [ Daily Life in the United States, 1920-1940 by David E. Kyvig Small Towns, Race Relations, The Depression, and More [ Ava’s Man by Rick Bragg [ Tobacco Road by Erskine Caldwell [ To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee [ Lie Down in Darkness by William Styron More information on the books in this list [ All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren and other reading suggestions can be found at [ The Storied South: Voices of Writers and Artists ed. -

Understanding the Other Europe: Philip Roth's

Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos, nº 17 (2013) Seville, Spain. ISSN 1133-309-X, pp. 13-24 UNDERSTANDING THE OTHER EUROPE: PHILIP ROTH’S WRITINGS ON PRAGUE1 MARTYNA BRYLA Universidad de Málaga [email protected] KEYWORDS Philip Roth; Prague; Eastern Europe; dissident writers; communism; Franz Kafka. PALABRAS CLAVES Philip Roth; Praga; Europa del Este; escritores disidentes; comunismo; Franz Kafka. ABSTRACT The aim of this essay is to explore the representation and significance of post -war Prague in the works of one of the finest contemporary American authors, Philip Roth. Kafka’s hometown is the locale of The Prague Orgy (1985) and one of David Kepesh’s stops on his summer tour of Europe in The Professor of Desire (1977). It also features prominently in the interviews and conversations conducted with and by Roth at the time when the Iron Curtain still separated Eastern Europe from the rest of the world. This essay analyzes Roth’s take on the complex Czechoslovak reality and discusses how the writer’s travels to Prague and his friendship with dissident authors shaped his views on the nature of literature and the position of the writer in society. The author also argues that through his writing Roth challenges certain Western stereotypes about cultural life under communism. RESUMEN El objetivo de este trabajo es explorar la representación y el significado de la Praga de la posguerra en la obra de uno de los más destacados autores norteamericanos contemporáneos, Philip Roth. La ciudad natal de Kafka es la localidad de The Prague Orgy (1985) y una de las paradas de David Kepesh en sus viajes por Europa en The Professor of Desire (1977). -

Fiction Award Winners 2019

1989: Spartina by John Casey 2016: The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen National Book 1988: Paris Trout by Pete Dexter 2015: All the Light We Cannot See by A. Doerr 1987: Paco’s Story by Larry Heinemann 2014: The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt Award 1986: World’s Fair by E. L. Doctorow 2013: Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 1985: White Noise by Don DeLillo 2012: No prize awarded 2011: A Visit from the Goon Squad “Established in 1950, the National Book Award is an 1984: Victory Over Japan by Ellen Gilchrist by Jennifer Egan American literary prize administered by the National 1983: The Color Purple by Alice Walker 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding Book Foundation, a nonprofit organization.” 1982: Rabbit Is Rich by John Updike 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout - from the National Book Foundation website. 1980: Sophie’s Choice by William Styron 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao 1979: Going After Cacciato by Tim O’Brien by Junot Diaz 2018: The Friend by Sigrid Nunez 1978: Blood Tie by Mary Lee Settle 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2017: Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward 1977: The Spectator Bird by Wallace Stegner 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks 2016: The Underground Railroad by Colson 1976: J.R. by William Gaddis 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson Whitehead 1975: Dog Soldiers by Robert Stone 2004: The Known World by Edward P. Jones 2015: Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson The Hair of Harold Roux 2003: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2014: Redeployment by Phil Klay by Thomas Williams 2002: Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2013: Good Lord Bird by James McBride 1974: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon 2001: The Amazing Adventures of 2012: Round House by Louise Erdrich 1973: Chimera by John Barth Kavalier and Clay by Michael Chabon 2011: Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward 1972: The Complete Stories 2000: Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 2010: Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon by Flannery O’Connor 1999: The Hours by Michael Cunningham 2009: Let the Great World Spin by Colum McCann 1971: Mr.