Understanding the Other Europe: Philip Roth's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Letters of William Styron

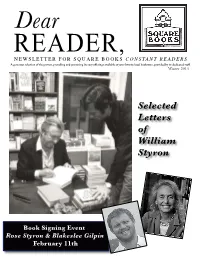

Dear Winter 2013 Selected Letters of William Styron Book Signing Event Rose Styron & Blakeslee Gilpin February 11th THE YEAR IN REVIEW 2012 With 2012 in rear view, we are very thankful for the many writers who came to us and the publishers who sent them to Square Books, as their books tend to dominate our bestseller list; some, like James Meek (The Heart Broke In, #30) and Lawrence Norfolk (John Saturnall’s Feast, #29), from as far as England – perhaps it’s the fascination with Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey (67) or J. K. Rowling’s Casual Vacancy (78). But as Dear Readers know, this list is usually crowded with those who live or have lived here, like Dean Wells’ Every Day by the Sun (22) or (long ago) James Meredith (A Mission From God, (10); William Faulkner’s Selected Stories (43), Ole Miss at Oxford, by Bill Morris (37), Mike Stewart’s Sporting Dogs and Retriever Training (39), John Brandon’s A Million Heavens (24), Airships (94), by Barry Hannah, Dream Cabinet by Ann Fisher-Wirth (87), Beginnings & Endings (85) by Ron Borne, Facing the Music (65) by Larry Brown, Neil White’s In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (35), the King twins’ Y’all Twins? (12), Tom Franklin’s Crooked Letter Crooked Letter (13), The Fall of the House of Zeus (15) by Curtis Wilkie, Julie Cantrell’s Into the Free (16), Ole Miss Daily Devotions (18), and two perennial local favorites Wyatt Waters’ Oxford Sketchbook (36) and Square Table (8), which has been in our top ten ever since it was published; not to forget Sam Haskell and Promises I Made My Mother (6) or John Grisham, secure in the top two spots with The Racketeer and Calico Joe, nor our friend Richard Ford, with his great novel, Canada (5). -

John Updike, a Lyrical Writer of the Middle-Class More Article Man, Dies at 76 Get Urba

LIKE RABBITS Welcome to TimesPeople TimesPeople Lets You Share and Discover the Bes Get Started HOME PAGE TODAY'S PAPER VIDEO MOST POPULAR TIMES TOPICS Books WORLD U.S. N.Y. / REGION BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE HEALTH SPORTS OPINION ARTS STYL ART & DESIGN BOOKS Sunday Book Review Best Sellers First Chapters DANCE MOVIES MUSIC John Updike, a Lyrical Writer of the Middle-Class More Article Man, Dies at 76 Get Urba By CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT Sig Published: January 28, 2009 wee SIGN IN TO den RECOMMEND John Updike, the kaleidoscopically gifted writer whose quartet of Cha Rabbit novels highlighted a body of fiction, verse, essays and criticism COMMENTS so vast, protean and lyrical as to place him in the first rank of E-MAIL Ads by Go American authors, died on Tuesday in Danvers, Mass. He was 76 and SEND TO PHONE Emmetsb Commerci lived in Beverly Farms, Mass. PRINT www.Emme REPRINTS U.S. Trus For A New SHARE Us Directly USTrust.Ba Lanco Hi 3BHK, 4BH Living! www.lancoh MOST POPUL E-MAILED 1 of 11 © 2009 John Zimmerman. All rights reserved. 7/9/2009 10:55 PM LIKE RABBITS 1. Month Dignit 2. Well: 3. GLOB 4. IPhon 5. Maure 6. State o One B 7. Gail C 8. A Run Meani 9. Happy 10. Books W. Earl Snyder Natur John Updike in the early 1960s, in a photograph from his publisher for the release of “Pigeon Feathers.” More Go to Comp Photos » Multimedia John Updike Dies at 76 A star ALSO IN BU The dark Who is th ADVERTISEM John Updike: A Life in Letters Related An Appraisal: A Relentless Updike Mapped America’s Mysteries (January 28, 2009) 2 of 11 © 2009 John Zimmerman. -

Philip Roth's Confessional Narrators: the Growth of Consciousness

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1979 Philip Roth's Confessional Narrators: The Growth of Consciousness. Alexander George Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation George, Alexander, "Philip Roth's Confessional Narrators: The Growth of Consciousness." (1979). Dissertations. 1823. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1823 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Alexander George PHILIP ROTH'S CONFESSIONAL NARRATORS: THE GROWTH OF' CONSCIOUSNESS by Alexander George A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 1979 ACKNOWLEDGE~£NTS It is a singular pleasure to acknowledge the many debts of gratitude incurred in the writing of this dissertation. My warmest thanks go to my Director, Dr. Thomas Gorman, not only for his wise counsel and practical guidance, but espec~ally for his steadfast encouragement. I am also deeply indebted to Dr. Paul Messbarger for his careful reading and helpful criticism of each chapter as it was written. Thanks also must go to Father Gene Phillips, S.J., for the benefit of his time and consideration. I am also deeply grateful for the all-important moral support given me by my family and friends, especially Dr. -

(For an Exceptional Debut Novel, Set in the South) Names Final Four

FOR RELEASE NOVEMBER 20 FIRST ANNUAL CROOK’S CORNER BOOK PRIZE (FOR AN EXCEPTIONAL DEBUT NOVEL, SET IN THE SOUTH) NAMES FINAL FOUR The linkages between good writing and good food and drink are clear and persistent. I can’t imagine a better means of celebrating their entwining than this innovative award. — John T. Edge CHAPEL HILL, NC – The Crook’s Corner Book Prize announced four finalists for the first annual Crook’s Corner Book Prize, to be awarded for an exceptional debut novel set in the American South. The winner will be announced January 6th. The four finalists are LEAVING TUSCALOOSA, by Walter Bennett (Fuze Publishing); CODE OF THE FOREST, by Jon Buchan (Joggling Board Press); A LAND MORE KIND THAN HOME, by Wiley Cash (William Morrow); and THE ENCHANTED LIFE OF ADAM HOPE, by Rhonda Riley (Ecco). “It was exciting to find so many great books—several of them from independent publishers (even micro-publishers)—emerging from our reading,” said Anna Hayes, founder and president of the Crook’s Corner Book Prize Foundation. “This grassroots effort to discover and champion books in general, Southern Literature in particular, is amazing and refreshing,” said Jamie Fiocco, owner of Flyleaf Books and president of the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance. “The Crook’s Corner Book Prize is a great example of what independent booksellers have been doing for years: finding top- quality reading experiences, regardless of the book’s origin—small or large publisher. Readers trust the rich literary history of the South to deliver a sense of place and great characters; now this Prize lets readers learn about the cream of the crop of new storytellers.” Intended to encourage emerging writers in a publishing environment that seems to change daily, the Prize is equally open to self-published authors and traditionally published authors. -

Women and Evil in Contemporary American Novels"

DOI: https://doi.org/10.22201/ffyl.01860526p.1990.4.954 The Sterile or Life-Denying Society: Women and Evil in Contemporary American Novels" Society is a joint-stock company, in which the members agree, for the beller securing ofhis bread to each share-holder, to surrender the librrty and culture of the eater. The virtue in most request is confonnity. Self-reliance is its aversion ... Whoso would be aman, must be a nonconfonnist. by Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Self-Reliance" . Charles MASINTON Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 1 At first glance, it might appear that contemporary American novelists have largely turned away from the age-old problem of evil to concern themselves with purely esthetic matters 01' with issues relating to a technological, urban, post-Christian society, an "enlightened" society in which what used to be understood as evil can be accounted for in psychological, sociological, political, 01' scientific terms. But this is not the case. While some of our serious, critically celebrated novelists since the end ofWorld War II - John Barth, Roben Coover, William H. Gass, and Vladimir Nabokov come to mind- have dedicated themselves principally to the formal and technical aspects of their craft, an imposing number of contemporary novelists recognize the reality of evil in human affairs and represent it in a wide variety of ways. In contrast to those writers named aboye, for whom novels are primarily objects of beauty and delight and not vehicles for com municating social 01' philosophical insights, most important American novelists still address the pressing issues of day-to-day existence, including the problem of evil. -

Philip Roth, Henry Roth and the History of the Jews

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 16 (2014) Issue 2 Article 9 Philip Roth, Henry Roth and the History of the Jews Timothy Parrish Florida State University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Literature Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Modern Literature Commons, and the Other Arts and Humanities Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Parrish, Timothy. "Philip Roth, Henry Roth and the History of the Jews." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 16.2 (2014): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.2411> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

Philip Roth Biography Appeared Before the Book Came Out, with Major Stories in Magazines and Literary Publications

Sexual Assault Allegations Against Biographer Halt Shipping of His Roth Book W.W. Norton, citing the accusations that the author, Blake Bailey, faces, said it would stop shipping and promoting his new best-selling book. “Philip Roth: The Biography” went on sale earlier this month.Credit...W.W. Norton, via Associated Press By Alexandra Alter and Rachel Abrams Published April 21, 2021Updated May 17, 2021 Earlier this month, the biographer Blake Bailey was approaching what seemed like the apex of his literary career. Reviews of his highly anticipated Philip Roth biography appeared before the book came out, with major stories in magazines and literary publications. It landed on the New York Times best-seller list this week. Now, allegations against Mr. Bailey, 57, have emerged, including claims that he sexually assaulted two women, one as recently as 2015, and that he behaved inappropriately toward middle school students when he was a teacher in the 1990s. His publisher, W.W. Norton, took swift and unusual action: It said on Wednesday that it had stopped shipments and promotion of his book. “These allegations are serious,” it said in a statement. “In light of them, we have decided to pause the shipping and promotion of ‘Philip Roth: The Biography’ pending any further information that may emerge.” Norton, which initially printed 50,000 copies of the title, has stopped a 10,000-copy second printing that was scheduled to arrive in early May. It has also halted advertising and media outreach, and events that Norton arranged to promote the book are being canceled. The pullback from the publisher came just days after Mr. -

John Updike and the Grandeur of the American Suburbs Oliver Hadingham, Rikkyo University, Japan the Asian Conference on Literatu

John Updike and the Grandeur of the American Suburbs Oliver Hadingham, Rikkyo University, Japan The Asian Conference on Literature, Librarianship & Archival Science 2016 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract The standing of John Updike (1932-2009), a multiple prize-winning author of more than 60 books, has suffered over the last two decades. Critics have recognized Updike’s skill as a writer of beautiful prose, but fail to include him among the highest rank of 20th century American novelists. What is most frustrating about the posthumous reputation of Updike is the failure by critics to fully acknowledge what is it about his books that makes them so enduringly popular. Updike combines beautifully crafted prose with something more serious: an attempt to clarify for the reader the truths and texture of America itself. Keywords: John Updike, middle-class, suburbia, postwar America iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org Over the last few decades the reputation of John Updike (1932-2009) has suffered greatly. Updike's doggedness and craft as a writer turned him into a multi-prize winning author of 23 novels, fourteen poetry collections, ten hefty collections of essays, two books of art criticism, a play, some children's books, and numerous short story collections. Yet such a prolific output and the numerous awards won have not placed him among the greats of 20th century American literature. He is remembered as someone who could write elegant prose, but to no lasting effect in articulating something worthwhile. Since the acclaim and prizes showered on Rabbit is Rich (1981) and Rabbit at Rest (1990), Updike has fallen out of favour with the literary world. -

Alice Walker Papers, Circa 1930-2014

WALKER, ALICE, 1944- Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Digital Material Available in this Collection Descriptive Summary Creator: Walker, Alice, 1944- Title: Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1061 Extent: 138 linear feet (253 boxes), 9 oversized papers boxes and 1 oversized papers folder (OP), 10 bound volumes (BV), 5 oversized bound volumes (OBV), 2 extraoversized papers folders (XOP) 2 framed items (FR), AV Masters: 5.5 linear feet (6 boxes and CLP), and 7.2 GB of born digital materials (3,054 files) Abstract: Papers of Alice Walker, an African American poet, novelist, and activist, including correspondence, manuscript and typescript writings, writings by other authors, subject files, printed material, publishing files and appearance files, audiovisual materials, photographs, scrapbooks, personal files journals, and born digital materials. Language: Materials mostly in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Selected correspondence in Series 1; business files (Subseries 4.2); journals (Series 10); legal files (Subseries 12.2), property files (Subseries 12.3), and financial records (Subseries 12.4) are closed during Alice Walker's lifetime or October 1, 2027, whichever is later. Series 13: Access to processed born digital materials is only available in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (the Rose Library). Use of the original digital media is restricted. The same restrictions listed above apply to born digital materials. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. -

Philip Roth by Erica Wagner for the Financial Times It Was Towards The

Philip Roth by Erica Wagner for the Financial Times It was towards the end of our hour-long conversation that Philip Roth asked me what I made of one of the characters in his novel The Humbling. It was 2009, the year his penultimate book was published, the first year of Barack Obama’s presidency. I had flown to New York on a day’s notice to meet with Roth in a bland conference room in the office of his agent, Andrew Wylie. I was glad I hadn’t had more warning; less time to worry about how this encounter with prickly titan of American letters would go. The protagonist of The Humbling is an actor, Simon Axler, sliding into despair as he ages. Drawn to suicide, he checks himself into a psychiatric hospital where he encounters a woman, Sybil Van Buren, who asks Axler to kill her husband -- he’s been abusing their daughter. Axler’s encounter with Van Buren is a strange subplot in this peculiar, unsatisfying novel that doesn’t rank among Roth’s best work. But he noticed that in the course of our talk I hadn’t mentioned her at all. Why was that? I didn’t know what to make of her, I said. I thought her story, her connection with Axler, was going to go in a different direction; I was puzzled by what Roth had done. The moment I said this it was as if I was suddenly observing myself from a great height. Philip Roth is sitting across from me, and I am telling him I don’t like what he’s done.