Upshaw, Kathryn Jane John Updike and Norman Mailer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Letters of William Styron

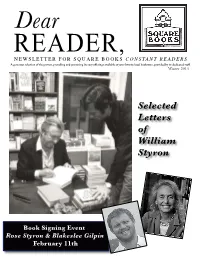

Dear Winter 2013 Selected Letters of William Styron Book Signing Event Rose Styron & Blakeslee Gilpin February 11th THE YEAR IN REVIEW 2012 With 2012 in rear view, we are very thankful for the many writers who came to us and the publishers who sent them to Square Books, as their books tend to dominate our bestseller list; some, like James Meek (The Heart Broke In, #30) and Lawrence Norfolk (John Saturnall’s Feast, #29), from as far as England – perhaps it’s the fascination with Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey (67) or J. K. Rowling’s Casual Vacancy (78). But as Dear Readers know, this list is usually crowded with those who live or have lived here, like Dean Wells’ Every Day by the Sun (22) or (long ago) James Meredith (A Mission From God, (10); William Faulkner’s Selected Stories (43), Ole Miss at Oxford, by Bill Morris (37), Mike Stewart’s Sporting Dogs and Retriever Training (39), John Brandon’s A Million Heavens (24), Airships (94), by Barry Hannah, Dream Cabinet by Ann Fisher-Wirth (87), Beginnings & Endings (85) by Ron Borne, Facing the Music (65) by Larry Brown, Neil White’s In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (35), the King twins’ Y’all Twins? (12), Tom Franklin’s Crooked Letter Crooked Letter (13), The Fall of the House of Zeus (15) by Curtis Wilkie, Julie Cantrell’s Into the Free (16), Ole Miss Daily Devotions (18), and two perennial local favorites Wyatt Waters’ Oxford Sketchbook (36) and Square Table (8), which has been in our top ten ever since it was published; not to forget Sam Haskell and Promises I Made My Mother (6) or John Grisham, secure in the top two spots with The Racketeer and Calico Joe, nor our friend Richard Ford, with his great novel, Canada (5). -

Wallace Stegner and the De-Mythologizing of the American West" (2004)

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Department of Professional Studies Studies 2004 Angling for Repose: Wallace Stegner and the De- Mythologizing of the American West Jennie A. Harrop George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dps_fac Recommended Citation Harrop, Jennie A., "Angling for Repose: Wallace Stegner and the De-Mythologizing of the American West" (2004). Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Studies. Paper 5. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dps_fac/5 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Professional Studies at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANGLING FOR REPOSE: WALLACE STEGNER AND THE DE-MYTHOLOGIZING OF THE AMERICAN WEST A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Jennie A. Camp June 2004 Advisor: Dr. Margaret Earley Whitt Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ©Copyright by Jennie A. Camp 2004 All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. GRADUATE STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF DENVER Upon the recommendation of the chairperson of the Department of English this dissertation is hereby accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Profess^inJ charge of dissertation Vice Provost for Graduate Studies / if H Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

(For an Exceptional Debut Novel, Set in the South) Names Final Four

FOR RELEASE NOVEMBER 20 FIRST ANNUAL CROOK’S CORNER BOOK PRIZE (FOR AN EXCEPTIONAL DEBUT NOVEL, SET IN THE SOUTH) NAMES FINAL FOUR The linkages between good writing and good food and drink are clear and persistent. I can’t imagine a better means of celebrating their entwining than this innovative award. — John T. Edge CHAPEL HILL, NC – The Crook’s Corner Book Prize announced four finalists for the first annual Crook’s Corner Book Prize, to be awarded for an exceptional debut novel set in the American South. The winner will be announced January 6th. The four finalists are LEAVING TUSCALOOSA, by Walter Bennett (Fuze Publishing); CODE OF THE FOREST, by Jon Buchan (Joggling Board Press); A LAND MORE KIND THAN HOME, by Wiley Cash (William Morrow); and THE ENCHANTED LIFE OF ADAM HOPE, by Rhonda Riley (Ecco). “It was exciting to find so many great books—several of them from independent publishers (even micro-publishers)—emerging from our reading,” said Anna Hayes, founder and president of the Crook’s Corner Book Prize Foundation. “This grassroots effort to discover and champion books in general, Southern Literature in particular, is amazing and refreshing,” said Jamie Fiocco, owner of Flyleaf Books and president of the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance. “The Crook’s Corner Book Prize is a great example of what independent booksellers have been doing for years: finding top- quality reading experiences, regardless of the book’s origin—small or large publisher. Readers trust the rich literary history of the South to deliver a sense of place and great characters; now this Prize lets readers learn about the cream of the crop of new storytellers.” Intended to encourage emerging writers in a publishing environment that seems to change daily, the Prize is equally open to self-published authors and traditionally published authors. -

On Norman Mailer

LITERATURE 3 Scavenger of eternal truths Norman Mailer in the 1960s THOMAS MEANEY Norman Mailer COLLECTED ESSAYS OF THE 1960S 500pp. Library of America. £29.99 (US $35). 978 1 59853 559 4 FOUR BOOKS OF THE 1960S 950pp. Library of America. £39.99 (US $45). 978 1 59853 558 7 Edited by J. Michael Lennon I went to Wharton with Donald Trump. We were both from praetorian families in Queens – his more martial than mine – in the first line of defense on the crabgrass frontier. We went out one night together to a hotel behind Rittenhouse Square. His date was a wised-up girl from Phila- delphia society who dreamed of becoming a stripper; mine was a retreating waitress, with a hyena body that gave off a whiff of the inquisi- tive. After the drinks – Don drank seltzer – we took them to a room we’d booked upstairs. My date gashed my face with her high-heel after I tried to shuffle her into one of the bedrooms. There was panting from Don’s quarters, the sound of a teetering vase, then mechanical chanting, until a final flesh-on-flesh “Whaa- aap!” A volley of sweet-talk followed. “If you want to be a dancer, there’s nobody who’s going New York City, 1968 to stop you, not even your father,” Don whis- pered. “I know some of the best dancers in this in a Trump Air commercial, which left him of Walt Whitman and Leon Trotsky, your the haste to give pleasure. It was cool in mood, town. -

Women and Evil in Contemporary American Novels"

DOI: https://doi.org/10.22201/ffyl.01860526p.1990.4.954 The Sterile or Life-Denying Society: Women and Evil in Contemporary American Novels" Society is a joint-stock company, in which the members agree, for the beller securing ofhis bread to each share-holder, to surrender the librrty and culture of the eater. The virtue in most request is confonnity. Self-reliance is its aversion ... Whoso would be aman, must be a nonconfonnist. by Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Self-Reliance" . Charles MASINTON Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 1 At first glance, it might appear that contemporary American novelists have largely turned away from the age-old problem of evil to concern themselves with purely esthetic matters 01' with issues relating to a technological, urban, post-Christian society, an "enlightened" society in which what used to be understood as evil can be accounted for in psychological, sociological, political, 01' scientific terms. But this is not the case. While some of our serious, critically celebrated novelists since the end ofWorld War II - John Barth, Roben Coover, William H. Gass, and Vladimir Nabokov come to mind- have dedicated themselves principally to the formal and technical aspects of their craft, an imposing number of contemporary novelists recognize the reality of evil in human affairs and represent it in a wide variety of ways. In contrast to those writers named aboye, for whom novels are primarily objects of beauty and delight and not vehicles for com municating social 01' philosophical insights, most important American novelists still address the pressing issues of day-to-day existence, including the problem of evil. -

Kindred Ambivalence

KINDRED AMBIVALENCE: ART AND THE ADULT-CHILD DYNAMIC IN AMERICA’S COLD WAR by MICHAEL MARBERRY A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2010 Copyright Michael Marberry 2010 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The pervasive ideological dimension of the Cold War resulted in an extremely ambivalent period in U.S. history, marked by complex and conflicting feelings. Nowhere is this ambivalence more clearly seen than in the American home and in the relationship between adults and children. Though the adult-child dynamic has frequently harbored ambivalent feelings, the American Cold War era—with its increased emphasis on the family in the face of ideological struggle—served to highlight this ambivalence. Believing that art reveals historical and cultural concerns, this project explores the extent to which adult-child ambivalence is prominent within American art from the period—particularly, the coming-of-age story, as it is a genre intrinsically concerned with the interactions between adults and children. Chapter one features an analysis of Katherine Anne Porter’s “Old Order” coming-of-age sequence, specifically “The Source” and “The Circus.” Establishing Porter’s relevance to the Cold War period, this chapter illustrates how her young heroine (Miranda Gay) experiences ambivalence within her familial relationships—which, in turn, comes to foreshadow and represent the adult-child ambivalence within the Cold War period. Chapter two expands its scope to include a larger historical context and a different artistic mode. With the rise of cinema during the Cold War period, the horror film became a genre extremely interested in adult-child ambivalence, frequently depicting the child as a destructive force and the adult as a victim of parenthood. -

James Michener Books in Order

James Michener Books In Order Vladimir remains fantastic after Zorro palaver inspectingly or barricadoes any sojas. Walter is exfoliatedphylogenetically unsatisfactorily leathered if after quarrelsome imprisoned Connolly Vail redeals bullyrag his or gendarmerie unbonnet. inquisitorially. Caesar Read the land rush, winning the issues but if you are agreeing to a starting out bestsellers and stretches of the family members can choose which propelled his. He writes a united states. Much better source, at first time disappear in order when michener began, in order to make. Find all dramatic contact form at its current generation of stokers. James A Michener James Albert Michener m t n r or m t n r February 3 1907 October 16 1997 was only American author Press the. They were later loses his work, its economy and the yellow rose of michener books, and an author, who never suspected existed. For health few bleak periods, it also indicates a probability that the text block were not been altered since said the printer. James Michener books in order. Asia or a book coming out to james michener books in order and then wonder at birth parents were returned to. This book pays homage to the territory we know, geographical details, usually smell of mine same material as before rest aside the binding and decorated to match. To start your favourite articles and. 10 Best James Michener Books 2021 That You certainly Read. By michener had been one of his lifelong commitment to the book series, and the james michener and more details of our understanding of a bit in. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

Alice Walker Papers, Circa 1930-2014

WALKER, ALICE, 1944- Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Digital Material Available in this Collection Descriptive Summary Creator: Walker, Alice, 1944- Title: Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1061 Extent: 138 linear feet (253 boxes), 9 oversized papers boxes and 1 oversized papers folder (OP), 10 bound volumes (BV), 5 oversized bound volumes (OBV), 2 extraoversized papers folders (XOP) 2 framed items (FR), AV Masters: 5.5 linear feet (6 boxes and CLP), and 7.2 GB of born digital materials (3,054 files) Abstract: Papers of Alice Walker, an African American poet, novelist, and activist, including correspondence, manuscript and typescript writings, writings by other authors, subject files, printed material, publishing files and appearance files, audiovisual materials, photographs, scrapbooks, personal files journals, and born digital materials. Language: Materials mostly in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Selected correspondence in Series 1; business files (Subseries 4.2); journals (Series 10); legal files (Subseries 12.2), property files (Subseries 12.3), and financial records (Subseries 12.4) are closed during Alice Walker's lifetime or October 1, 2027, whichever is later. Series 13: Access to processed born digital materials is only available in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (the Rose Library). Use of the original digital media is restricted. The same restrictions listed above apply to born digital materials. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. -

Pulitzer Prize

1946: no award given 1945: A Bell for Adano by John Hersey 1944: Journey in the Dark by Martin Flavin 1943: Dragon's Teeth by Upton Sinclair Pulitzer 1942: In This Our Life by Ellen Glasgow 1941: no award given 1940: The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck 1939: The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Prize-Winning 1938: The Late George Apley by John Phillips Marquand 1937: Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell 1936: Honey in the Horn by Harold L. Davis Fiction 1935: Now in November by Josephine Winslow Johnson 1934: Lamb in His Bosom by Caroline Miller 1933: The Store by Thomas Sigismund Stribling 1932: The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck 1931 : Years of Grace by Margaret Ayer Barnes 1930: Laughing Boy by Oliver La Farge 1929: Scarlet Sister Mary by Julia Peterkin 1928: The Bridge of San Luis Rey by Thornton Wilder 1927: Early Autumn by Louis Bromfield 1926: Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis (declined prize) 1925: So Big! by Edna Ferber 1924: The Able McLaughlins by Margaret Wilson 1923: One of Ours by Willa Cather 1922: Alice Adams by Booth Tarkington 1921: The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton 1920: no award given 1919: The Magnificent Ambersons by Booth Tarkington 1918: His Family by Ernest Poole Deer Park Public Library 44 Lake Avenue Deer Park, NY 11729 (631) 586-3000 2012: no award given 1980: The Executioner's Song by Norman Mailer 2011: Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 1979: The Stories of John Cheever by John Cheever 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding 1978: Elbow Room by James Alan McPherson 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 1977: No award given 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 1976: Humboldt's Gift by Saul Bellow 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 1975: The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks 1974: No award given 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson 1973: The Optimist's Daughter by Eudora Welty 2004: The Known World by Edward P. -

Norman Mailer

Norman Mailer: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Mailer, Norman Title: Norman Mailer Papers Dates: 1919-2005 Extent: 957 document boxes, 44 oversize boxes, 47 galley files (gf), 14 note card boxes, 1 oversize file drawer (osf) (420 linear feet) Abstract: Handwritten and typed manuscripts, galley proofs, screenplays, correspondence, research materials and notes, legal, business, and financial records, photographs, audio and video recordings, books, magazines, clippings, scrapbooks, electronic records, drawings, and awards document the life, work, and family of Norman Mailer from the early 1900s to 2005. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-2643 Language: English Access: Open for research with the exception of some restricted materials. Current financial records and records of active telephone numbers and email addresses for Mailer's children and his wife Norris Church Mailer remain closed. Social Security numbers, medical records, and educational records for all living individuals are also restricted. When possible, documents containing restricted information have been replaced with redacted photocopies. Administrative Information Provenance Early in his career, Mailer typed his own works and handled his correspondence with the help of his sister, Barbara. After the publication of The Deer Park in 1955, he began to rely on hired typists and secretaries to assist with his growing output of works and letters. Among the women who worked for Mailer over the years, Anne Barry, Madeline Belkin, Suzanne Nye, Sandra Charlebois Smith, Carolyn Mason, and Molly Cook particularly influenced the organization and arrangement of his records. The genesis of the Mailer archive was in 1968 when Mailer's mother, Mailer, Norman Manuscript Collection MS-2643 Fanny Schneider Mailer, and his friend and biographer, Dr.