Chapter 6 – Shock NOTE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suplento1 Volumen 71 En

S1 Volumen 71 Mayo 2015 Revista Española de Vol. 71 Supl. 1 • Mayo 2015 Vol. Clínica e Investigación Órgano de expresión de la Sociedad Española de SEINAP Investigación en Nutrición y Alimentación en Pediatría Sumario XXX CONGRESO DE LA SOCIEDAD espaÑOLA DE CUIDADOS INTENSIVOS PEDIÁTRICOS Toledo, 7-9 de mayo de 2015 MESA REDONDA: ¿HACIA DÓNDE VAMOS EN LA MESA REDONDA: EL PACIENTE AGUDO MONITORIZACIÓN? CRONIFICADO EN UCIP 1 Monitorización mediante pulsioximetría: ¿sólo saturación 47 Nutrición en el paciente crítico de larga estancia en UCIP. de oxígeno? P. García Soler Z. Martínez de Compañón Martínez de Marigorta 3 Avances en la monitorización de la sedoanalgesia. S. Mencía 53 Traqueostomía, ¿cuándo realizarla? M.A. García Teresa Bartolomé y Grupo de Sedoanalgesia de la SECIP 60 Los cuidados de enfermería, ¿un reto? J.M. García Piñero 8 Avances en neuromonitorización. B. Cabeza Martín CHARLA-COLOQUIO SESIÓN DE PUESTA AL DÍA: ¿ES BENEFICIOSA LA 64 La formación en la preparación de las UCIPs FLUIDOTERAPIA PARA MI PACIENTE? españolas frente al riesgo de epidemias infecciosas. 13 Sobrecarga de líquidos y morbimortalidad asociada. J.C. de Carlos Vicente M.T. Alonso 68 Lecciones aprendidas durante la crisis del Ébola: 20 Estrategias de fluidoterapia racional en Cuidados experiencia del intensivista de adultos. J.C. Figueira Intensivos Pediátricos. P. de la Oliva Senovilla Iglesias 72 El niño con enfermedad por virus Ébola: un nuevo reto MESA REDONDA: INDICADORES DE CALIDAD para el intensivista pediátrico. E. Álvarez Rojas DE LA SECIP 23 Evolución de la cultura de seguridad en UCIP. MESA REDONDA: UCIP ABIERTAS 24 HORAS, La comunicación efectiva. -

Pediatric Shock

REVIEW Pediatric shock Usha Sethuraman† & Pediatric shock accounts for significant mortality and morbidity worldwide, but remains Nirmala Bhaya incompletely understood in many ways, even today. Despite varied etiologies, the end result †Author for correspondence of pediatric shock is a state of energy failure and inadequate supply to meet the metabolic Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Division of demands of the body. Although the mortality rate of septic shock is decreasing, the severity Emergency Medicine, is on the rise. Changing epidemiology due to effective eradication programs has brought in Carman and Ann Adams new microorganisms. In the past, adult criteria had been used for the diagnosis and Department of Pediatrics, 3901 Beaubien Boulevard, management of septic shock in pediatrics. These have been modified in recent times to suit Detroit, MI 48201, USA the pediatric and neonatal population. In this article we review the pathophysiology, Tel.: +1 313 745 5260 epidemiology and recent guidelines in the management of pediatric shock. Fax: +1 313 993 7166 [email protected] Shock is an acute syndrome in which the circu- to generate ATP. It is postulated that in the face of latory system is unable to provide adequate oxy- prolonged systemic inflammatory insult, overpro- gen and nutrients to meet the metabolic duction of cytokines, nitric oxide and other medi- demands of vital organs [1]. Due to the inade- ators, and in the face of hypoxia and tissue quate ATP production to support function, the hypoperfusion, the body responds by turning off cell reverts to anaerobic metabolism, causing the most energy-consuming biophysiological acute energy failure [2]. -

Fluid Resuscitation in Trauma Patients: What Should We Know?

REVIEW CURRENT OPINION Fluid resuscitation in trauma patients: what should we know? Silvia Coppola, Sara Froio, and Davide Chiumello Purpose of review Fluid resuscitation in trauma patients could reduce organ failure, until blood components are available and hemorrhage is controlled. However, the ideal fluid resuscitation strategy in trauma patients remains a debated topic. Different types of trauma can require different types of fluids and different volume of infusion. Recent findings There are few randomized controlled trials investigating the efficacy of fluids in trauma patients. There is no evidence that any type of fluids can improve short-term and long-term outcome in these patients. The main clinical evidence emphasizes that a restrictive fluid resuscitation before surgery improves outcome in patients with penetrating trauma. Fluid management of blunt trauma patients, in particular with coexisting brain injury, remains unclear. Summary In order to focus on the state of the art about this topic, we review the current literature and guidelines. Recent studies have underlined that the correct fluid resuscitation strategy can depend on the type of trauma condition: penetrating, blunt, brain injury or a combination of them. Of course, further studies are needed to investigate the impact of a specific fluid strategy on different type and severity of trauma. Keywords blunt trauma, colloids, crystalloids, fluid resuscitation, penetrating trauma INTRODUCTION In the literature, there is little evidence that one type of fluid compared with another can improve Traumatic death is the main cause of life years lost & worldwide [1]. Hemorrhage is responsible for almost survival or can be more effective [4 ,6]. Few rando- 50% of deaths in the first 24 h after trauma [2,3]. -

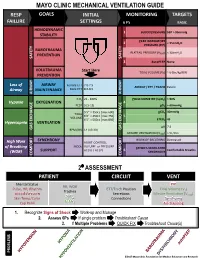

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain. -

Approach to Shock.” These Podcasts Are Designed to Give Medical Students an Overview of Key Topics in Pediatrics

PedsCases Podcast Scripts This is a text version of a podcast from Pedscases.com on “Approach to Shock.” These podcasts are designed to give medical students an overview of key topics in pediatrics. The audio versions are accessible on iTunes or at www.pedcases.com/podcasts. Approach to Shock Developed by Dr. Dustin Jacobson and Dr Suzanne Beno for PedsCases.com. December 20, 2016 My name is Dustin Jacobson, a 3rd year pediatrics resident from the University of Toronto. This podcast was supervised by Dr. Suzanne Beno, a staff physician in the division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine at the University of Toronto. Today, we’ll discuss an approach to shock in children. First, we’ll define shock and understand it’s pathophysiology. Next, we’ll examine the subclassifications of shock. Last, we’ll review some basic and more advanced treatment for shock But first, let’s start with a case. Jonny is a 6-year-old male who presents with lethargy that is preceded by 2 days of a diarrheal illness. He has not urinated over the previous 24 hours. On assessment, he is tachycardic and hypotensive. He is febrile at 40 degrees Celsius, and is moaning on assessment, but spontaneously breathing. We’ll revisit this case including evaluation and management near the end of this podcast. The term “shock” is essentially a ‘catch-all’ phrase that refers to a state of inadequate oxygen or nutrient delivery for tissue metabolic demand. This broad definition incorporates many causes that eventually lead to this end-stage state. Basic oxygen delivery is determined by cardiac output and content of oxygen in the blood. -

Hypothesis Spinal Shock and `Brain Death': Somatic Pathophysiological

Spinal Cord (1999) 37, 313 ± 324 ã 1999 International Medical Society of Paraplegia All rights reserved 1362 ± 4393/99 $12.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/sc Hypothesis Spinal shock and `brain death': Somatic pathophysiological equivalence and implications for the integrative-unity rationale DA Shewmon*,1 1Pediatric Neurology, UCLA Medical School, Los Angeles, California, USA The somatic pathophysiology of high spinal cord injury (SCI) not only is of interest in itself but also sheds light on one of the several rationales proposed for equating `brain death' (BD) with death, namely that the brain confers integrative unity upon the body, which would otherwise constitute a mere conglomeration of cells and tissues. Insofar as the neuropathology of BD includes infarction down to the foramen magnum, the somatic pathophysiology of BD should resemble that of cervico-medullary junction transection plus vagotomy. The endocrinologic aspects can be made comparable either by focusing on BD patients without diabetes insipidus or by supposing the victim of high SCI to have pre-existing therapeutically compensated diabetes insipidus. The respective literatures on intensive care for BD organ donors and high SCI corroborate that the two conditions are somatically virtually identical. If SCI victims are alive at the level of the `organism as a whole', then so must be BD patients (the only signi®cant dierence being consciousness). Comparison with SCI leads to the conclusion that if BD is to be equated with death, a more coherent reason must be adduced than that the body as a biological organism is dead. Keywords: brain death; spinal cord injury; spinal shock; integrative functions; somatic integrative unity; organism as a whole Introduction Spinal shock is a transient functional depression of the society; its legal de®nition is culturally relative, and structurally intact cord below a lesion, following acute most modern societies happen to have chosen to spinal cord injury (SCI). -

To Standardize Blood Pressure Goals in Bleeding Trauma Patients Undergoing Active Resuscitation

Division of Acute Care Surgery Clinical Practice Policies, Guidelines, and Algorithms: Controlled Resuscitation in Trauma Patients Clinical Practice Guideline Original Date: 06/2017 Purpose: To standardize blood pressure goals in bleeding trauma patients undergoing active resuscitation. Recommendations: Patient population Recommendation Adult blunt trauma patient without traumatic Resuscitate to a SBP >70 mmHg until hemorrhage brain injury is controlled Adult penetrating trauma patient without Resuscitate to a MAP > 50 mmHg or SBP >70 traumatic brain injury mmHg until hemorrhage controlled (GRADE Level of Quality – moderate; USPSTF strength of recommendation – B [intervention is recommended]) *Note: there is increasing interest in and use of resuscitative balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA). When used correctly, REBOA dramatically decreases blood pressure distal to the site of hemorrhage and, as such, is complimentary to controlled resuscitation, not contradictory. Summary of Public Health Impact: In 2013, injury was the most common cause of death among people ages 1-44 years, accounting for 59% of all deaths in this age range. There were over 192,900 deaths from injury, approximately one every 3 minutes.1 Since trauma is a disease of the young, injury accounts for the most life-years lost than any other disease – 30% of all life years lost in the U.S. compared to cancer 16% and heart disease 12%.2 Truncal hemorrhage accounts for 20-40% of trauma deaths occurring after hospital admission and continues to be a leading cause of potentially survivable deaths.3,4 This is despite a significant amount of time and healthcare resources attempting to address this problem, including: implementation of trauma systems5, utilization of in-house trauma surgeons6, and development of hemostatic resuscitation,7 to name a few. -

RDCR – PRINCIPLES NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen REMOTE DAMAGE CONTROL RESUSCITATION

NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen RDCR – PRINCIPLES NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen REMOTE DAMAGE CONTROL RESUSCITATION ¡ Is the implementation of damage control principles in austere environments NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen DAMAGE CONTROL RESUSCITATION: NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen TEMPORARY HEMORRHAGE CONTROL NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen PERMISSIVE HYPOTENSION NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen HEMOSTATIC RESUSCITATION NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen DAMAGE CONTROL SURGERY (DAMAGE CONTROL RADIOLOGICAL INTERVENTION) NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen RESTORING ORGAN PERFUSION IN ICU NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen PERMISSIVE HYPOTENSION: “PRESERVING COAGULATION, REDUCING BLEEDING WHILE SACRIFISING PERFUSION” NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen PERMISSIVE HYPOTENSION Goals of Fluid Resuscitation Therapy • Improved state of consciousness (if no TBI) • Palpable radial pulse corresponds roughly to systolic blood pressure of 80 mm Hg?? • Avoid over-resuscitation of shock from torso wounds. • Too much fluid volume may make internal hemorrhage worse by “Popping the Clot.” NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen ¡ Not a treatment ¡ Necessary evil?? ¡ Evidence???? Bicknell WH, Wall MJ, Pepe PE, Martin RR, Ginger VF, Allen MK, et al. Immediate versus delayed fluid resuscitation for hypotensive patients with penetrating torso injuries. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1105-9 Turner J, Nicholl J, Webber L, Cox H, Dixon S, Yates D. A randomised controlled trial of prehospital intravenous fluid replacement therapy in serious trauma. Health Technology Assessment 2000;4:1-57. Dutton RP, Mackenzie CF, Scalae TM. Hypotensive resuscitation during active haemorrhage: impact on hospital mortality. J Trauma 2002;52:1141-6. SAFE Study Investigators; Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group; Australian Red Cross Blood Service; George Institute for International Health, Myburgh J, Cooper DJ, et al. Saline or albumin for fluid resuscitation in patients with traumatic brain injury. -

Permissive Hypotension: Changing Tide of Trauma Fluid Resuscitation

Permissive Hypotension Jeff Myers, DO, EdM, NREMT‐P, FAAEM June 2009 [email protected] Permissive Hypotension: Changing Tide of Trauma Fluid Resuscitation Jeff Myers, D.O., Ed.M., NREMT-P, FAAEM Clinical Assistant Professor Emergency Medicine SUNY-Buffalo, Buffalo, NY [email protected] http://ems-ed.photoemsdoc.com/ 716.898.3525 Objectives: Describe the history of fluids in trauma resuscitation Understand the pathophysiology of hemorrhagic shock Understand the rationale for limiting IV fluids during trauma resuscitation History of Fluid Resuscitation: Traditional resuscitation guidelines ¾ 2 large bore IVs ¾ Infusion of 2 liters normal saline or lactated ringers Hypotension in Trauma occurs in ________ of both blunt and penetrating trauma victims. The civilian rate is approximately ________ and the recent military rate is ________ ¾ Approximately _____ of victims of trauma who are hypotensive die early, either _____________ or ___________________ and are _____________________________. This rate has been stable since the Crimean War and is not affected by trauma system development ¾ Approximately _____ of victims of trauma who are hypotensive are hypotensive from _______________________________ causes. These causes include: o _______________________________ o _______________________________ o _______________________________ o _______________________________ o _______________________________ o _______________________________ ¾ Approximately _____ of victims of trauma who are hypotensive are hypotensive secondary to _______________________ and are the focus of the discussion. Cannon, Fraser, Cowell. Preventative treatment of wound shock. JAMA 1918 noted poor outcomes with IV Fluid resuscitation Page 1 of 8 Permissive Hypotension Jeff Myers, DO, EdM, NREMT‐P, FAAEM June 2009 [email protected] ¾ “Inaccessible or uncontrolled source of blood loss should not be treated with intravenous fluids until the time of surgical control” Beecher. -

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Diagnosis and Management

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Draft for consultation Abdominal aortic aneurysm: diagnosis and management Evidence review Q: Permissive hypotension during transfer of people with ruptured AAA to regional vascular services NICE guideline <number> Evidence reviews May 2018 Draft for Consultation Commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION Error! No text of specified style in document. Disclaimer The recommendations in this guideline represent the view of NICE, arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. When exercising their judgement, professionals are expected to take this guideline fully into account, alongside the individual needs, preferences and values of their patients or service users. The recommendations in this guideline are not mandatory and the guideline does not override the responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or their carer or guardian. Local commissioners and/or providers have a responsibility to enable the guideline to be applied when individual health professionals and their patients or service users wish to use it. They should do so in the context of local and national priorities for funding and developing services, and in light of their duties to have due regard to the need to eliminate unlawful discrimination, to advance equality of opportunity and to reduce health inequalities. Nothing in this guideline should be interpreted in a way that would be inconsistent with compliance with those duties. NICE guidelines cover health and care in England. Decisions on how they apply in other UK countries are made by ministers in the Welsh Government, Scottish Government, and Northern Ireland Executive. -

Polytrauma Shock • Trauma Related Costs in the U.S

POLYTRAUMA SHOCK • TRAUMA RELATED COSTS IN THE U.S. 400 BILLION $ • 3.8 MILLION DEATHS PER YEAR • THE LEADING CAUSE OF DEATH IN PERSONS AGED 1 TO 45 IN THE MOST DEVELOPED COUNTRIES • TRIMODAL DEATH DISTRIBUTION 1. SECONDS, MINS FOLLOWING INJURY DUE TO BRAIN, C. SPINE, LARGE VESSEL INJ. 2. 1-2 HOURS FOLLOWING INJURY DUE TO EPIDURAL HAEMATOMAS, BLEEDINGS GOLDEN HOUR 3. SEVERAL DAYS FOLLOWING INJURY DUE TO M.O.F., SEPSIS TRIMODAL DEATH DISTRIBUTION 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% HOURS 0 1 2 3 4 WEEKS 1 2 3 4 TRIMODAL BIMODAL? THE SECOND GROUP IS DECREASING DUE TO PROPER TREATMENT GOLDEN HOUR NOT ONLY SALVAGEABILITY BUT MANY LATE PROBLEMS (SIRS, MOF) ARE THE CONSEQUENCES OF THE PRIMARY HYPOXIA AND MEDIATOR RELEASE SILVER DAY BRONZE WEEK PLATINA 10 MIN DEFINITION OF POLYTRAUMA A. INJURY TO ONE OR MORE BODY REGIONS OR ORGANS OF WHICH ONE, OR THEIR COMBINATIONS IS LIFE THREATENING B. INJURY TO MORE BODY REGIONS FOLLOWING WHICH, DURING TREATMENT, WE HAVE TO MAKE COMPROMISES C. INJURY TO HOLLOW ORGANS + INJURY TO EXTREMITIES D. INJURY DEFINED BY A SCORING SYSTEM TRAUMA SCORE NUMBER OF BREATHS PER MIN 0-4 INTENSITY OF BREATHING 0-1 SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE 0-4 CAPILLARY REFILL 0-2 GLASGOW COMA SCALE 0-5 POSSIBILITY FOR SURVIVAL 16+ <2 99% 0% GLASGOW COMA SCALE EYE OPENING SPONTANEOUS 4 TO SPEECH 3 TO PAIN 2 NONE 1 BEST MOTOR RESPONSE OBEYS COMMANDS 6 LOCALIZES PAIN 5 NORMAL FLEXION 4 ABNORMAL FLEXION 3 EXTENSION 2 NONE 1 VERBAL RESPONSE ORIENTED 5 CONFUSED CONVERS. 4 WORDS 3 SOUNDS 2 NOTHING 1 ABBREVIATED INJURY SCALE (ISS) 1 MILD 2 MEDIUM 3 SEVERE 4 VERY -

Definition Shock Is a Life-Threatening Condition That Occurs When the Body

Shock Definition Shock is a life-threatening condition that occurs when the body is not getting enough blood flow. This can damage multiple organs. Shock requires immediate medical treatment and can get worse very rapidly. Considerations Major classes of shock include: • Cardiogenic shock (associated with heart problems) • Hypovolemic shock (caused by inadequate blood volume) • Anaphylactic shock (caused by allergic reaction) • Septic shock (associated with infections) • Neurogenic shock (caused by damage to the nervous system) Causes Shock can be caused by any condition that reduces blood flow, including: • Heart problems (such as heart attack or heart failure ) • Low blood volume (as with heavy bleeding or dehydration ) • Changes in blood vessels (as with infection or severe allergic reactions ) Shock is often associated with heavy external or internal bleeding from a serious injury. Spinal injuries can also cause shock. Toxic shock syndrome is an example of a type of shock from an infection. Symptoms A person in shock has extremely low blood pressure. Depending on the specific cause and type of shock, symptoms will include one or more of the following: • Anxiety or agitation • Confusion • Pale, cool, clammy skin • Bluish lips and fingernails • Dizziness , light-headedness, fainting or unconsciousness • Profuse sweating , moist skin • Rapid but weak pulse • Shallow breathing • Chest pain First Aid • Call 911 for immediate medical help. • Check the person's airways, breathing, and circulation. If necessary, begin rescue breathing and CPR. • Even if the person is able to breathe on his or her own, continue to check rate of breathing at least every 5 minutes until help arrives. • If the person is conscious and does NOT have an injury to the head, leg, neck, or spine, place the person in the shock position.