Myanmar-China Intelligence Report (Pdf) Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter on Myanmar to ASEAN and ASEAN Dialogue Partners

Open Letter on Myanmar to ASEAN and ASEAN Dialogue Partners To: ASEAN Leaders H.E. Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Mu’izzaddin Waddaulah, Prime Minister of Brunei H.E Hun Sen, Prime Minister of Cambodia H.E Joko Widodo, President of Indonesia H.E Thongloun Sisoulith, Prime Minister of Laos H.E Tan Sri Muhyiddin Haji Mohd Yassin, Prime Minister of Malaysia H.E Rodrigo Roa Duterte, President of the Philippines H.E Lee Hsien Loong, Prime Minister of Singapore H.E Prayut Chan-o-cha, Prime Minister of Thailand H.E. Nguyen Xuan Phuc, Prime Minister of Vietnam CC: ASEAN Dialogue Partners H.E. Will Nankervis, Ambassador of Australia to ASEAN H.E. Diedrah Kelly, Ambassador of Canada to ASEAN H.E. Deng Xijun, Ambassador of China to ASEAN H.E. Igor Driesmans, Ambassador of the European Union to ASEAN H.E. Shri Jayant N. Khobragade, Ambassador of India to ASEAN H.E. Chiba Akira, Ambassador of Japan to ASEAN H.E. Lim Sungnam, Ambassador of Korea to ASEAN H.E. Pam Dunn, Ambassador of New Zealand to ASEAN H.E. Alexander Ivanov, Ambassador of Russia to ASEAN H.E. Melissa A. Brown, Chargé d’Affaires, a.i., U.S. Mission to ASEAN 4 May 2021 Re: ASEAN's Consensus on Myanmar Your Excellencies, It has been just over a week since a Five-Point Consensus on Myanmar was reached at the ASEAN Leaders’ Meeting on 24 April 2021 between all ASEAN leaders and Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. Although the consensus called for an immediate cessation of violence in Myanmar, there have been at least 18 more killings and 246 more arrests by the junta since. -

Taihe Civilizations Forum Content Highlights

2019 Taihe Civilizations Forum Content Highlights SEPTENBER 6-8, 2019 About Taihe Institute 1 Introduction of the Taihe Civilizations Forum 3 Speeches at the Opening Ceremony 5 Keynote Speeches at the Opening Ceremony 13 •Our Future Must Be the Best of Times 13 •In the Age of Big Data, the Data Subject is in the People, the Sovereignty is in the Country 17 •Enhance Mutual Trust and Seek Security Together 23 •Actively Serve the “Belt and Road” Initiative, Create an Upgraded Version of Vocational Education Exchange and Cooperation 28 •Sharing 5G, Cooperation and Win-Win 35 Summary of Individual Views at the Sub-sessions 39 Summary of Signifcant Viewpoints at the Sub-sessions 71 Media Coverage 93 About Taihe Institute Taihe About About Taihe Institute Founded in 2013 in Beijing, China, Taihe Institute is an international think tank which takes “collaborating of global elites, searching for common values” as its duty, and provides basis for the decision-making on the development of China and intelligent support for the communications of the world. Taihe focuses specifically in areas such as people-to-people exchange, international politics, religion, science and technology, education, culture, fnance and economics, etc. Taihe has taken programs entrusted by the central government of China. Besides, the research products are distributed internationally, and the signifcant products are published in the form of book series of Taihe Institute. Taihe has built up close connections with nearly hundreds of both domestic and international organizations through academic exchange and non-offcial activities. Taihe is the member of the Belt and Road Studies Network and the Belt and Road Initiative International Green Development Coalition. -

Burma Holds Peace Conference

CRS INSIGHT Burma Holds Peace Conference September 8, 2016 (IN10566) | Related Author Michael F. Martin | Michael F. Martin, Specialist in Asian Affairs ([email protected], 7-2199) In what many observers hope could be a step toward ending Burma's six-decade long, low-grade civil war and establishing a process eventually leading to reconciliation and possibly the formation of a democratic federated state, over 1,400 representatives of ethnic political parties, ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), the government in Naypyitaw and its military (Tatmadaw), and other concerned parties attended a peace conference in Naypyitaw, Burma, on August 31–September 3, 2016. Convened by Aung San Suu Kyi, State Counsellor for the government in Naypyitaw, the conference was called the "21st Century Panglong Peace Conference," a reference to a similar event convened by Aung San Suu Kyi's father, General Aung San, in 1947 that led to the creation of the independent state of Burma. Aung San Suu Kyi stated that she had hoped the conference would be an initial gathering of all concerned parties to share views for the future of a post-conflict Burma. Progress at the conference appeared to be hampered by the Tatmadaw's objection to inviting three EAOs to the conference, and two other ethnic organizations downgrading their participation. In addition, differences over protocol matters during the conference were perceived by some EAO representatives as deliberate disrespect on the part of the organizers. Statements presented by Commander-in-Chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing and representatives of several EAOs, moreover, indicated a serious gap in their visions of a democratic federated state of Burma and the path to achieving that goal. -

TI Observer Vol.07 TI Observer Volume 07 April 2021

TI Observer Vol.07 TI Observer TI Observer Volume 07 Volume April 2021 by Taihe Institute TI Observer 2 Contents Polyphonic Music in U.S.-China Relations: Time to Avoid the Trap’s Jaws Wang Xiangsui 03 Can China and the U.S. return to status quo ante in economic relations? Interview with Dr. J.M.F. Blanchard 06 Cover Story 11 Friend or Foe? — Cooperation & Competition in China-U.S. Relations (Part I — Cooperation) Introduction Overview of Possible Areas of Cooperation Between China and the U.S. i. Climate, Environment and Decarbonizing the Global Economy ii. Science, Space and Cybersecurity iii. Global Pandemics, Public Healthcare and Building a Global Disease Surveillance Network iv. Poverty Alleviation and Food Safety & Security v. Green Energy vi. Cooperation on Regional Hotspots (Myanmar, North Korea, Iran) vii. Counterterrorism viii. Financial Crisis Mitigation TI Observer · Volume 07 Polyphonic Music in U.S.-China Relations: 3 Time to Avoid the Trap’s Jaws Polyphonic Music in U.S.-China Relations: Time to Avoid the Trap’s Jaws (source: unsplash.com) About Wang Xiangsui the Senior Fellow of Taihe Institute Author Director of the Center for Strategic Studies, Beihang University China and the United States are regularly represented as two top league teams fiercely competing in the global arena and concurrently falling into the “Thucydides Trap”, as originally forewarned and discouraged by China’s President Xi Jinping in 2015. Today, a number of insightful people still see the shimmer of how China and the U.S. can cooperate. The intelligent choice for matching opponents when making close chase on the running track of human history is to focus on improving themselves rather than tripping over one another. -

Pangolin Trade in the Mong La Wildlife Market and the Role of Myanmar in the Smuggling of Pangolins Into China

Global Ecology and Conservation 5 (2016) 118–126 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Original research article Pangolin trade in the Mong La wildlife market and the role of Myanmar in the smuggling of pangolins into China Vincent Nijman a, Ming Xia Zhang b, Chris R. Shepherd c,∗ a Oxford Wildlife Trade Research Group, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK b Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Gardens, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Mengla, China c TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia article info a b s t r a c t Article history: We report on the illegal trade in live pangolins, their meat, and their scales in the Special Received 7 November 2015 Development Zone of Mong La, Shan State, Myanmar, on the border with China, and Received in revised form 18 December 2015 present an analysis of the role of Myanmar in the trade of pangolins into China. Mong Accepted 18 December 2015 La caters exclusively for the Chinese market and is best described as a Chinese enclave in Myanmar. We surveyed the morning market, wildlife trophy shops and wild meat restaurants during four visits in 2006, 2009, 2013–2014, and 2015. We observed 42 bags Keywords: of scales, 32 whole skins, 16 foetuses or pangolin parts in wine, and 27 whole pangolins for Burma CITES sale. Our observations suggest Mong La has emerged as a significant hub of the pangolin Conservation trade. The origin of the pangolins is unclear but it seems to comprise a mixture of pangolins Manis from Myanmar and neighbouring countries, and potentially African countries. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

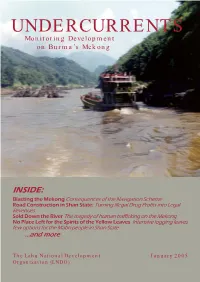

UNDERCURRENTS Monitoring Development on Burma’S Mekong

UNDERCURRENTS Monitoring Development on Burma’s Mekong INSIDE: Blasting the Mekong Consequences of the Navigation Scheme Road Construction in Shan State: Turning Illegal Drug Profits into Legal Revenues Sold Down the River The tragedy of human trafficking on the Mekong No Place Left for the Spirits of the Yellow Leaves Intensive logging leaves few options for the Mabri people in Shan State ...and more The Lahu National Development January 2005 Organization (LNDO) The Mekong/ Lancang The Mekong River is Southeast Asia’s longest, stretching from its source in Tibet to the delta of Vietnam. Millions of people depend on it for agriculture and fishing, and accordingly it holds a special cultural significance. For 234 kilometers, the Mekong forms the border between Burma’s Shan State and Luang Nam Tha and Bokeo provinces of Laos. This stretch includes the infamous “Golden Triangle”, or where Burma, Laos and Thailand meet, which has been known for illicit drug production. Over 22,000 primarily indigenous peoples live in the mountainous region of this isolated stretch of the river in Burma. The main ethnic groups are Akha, Shan, Lahu, Sam Tao (Loi La), Chinese, and En. The Mekong River has a special significance for the Lahu people. Like the Chinese, we call it the Lancang, and according to legends, the first Lahu people came from the river’s source. Traditional songs and sayings are filled with references to the river. True love is described as stretching form the source of the Mekong to the sea. The beauty of a woman is likened to the glittering scales of a fish in the Mekong. -

Mong La: Business As Usual in the China-Myanmar Borderlands

Mong La: Business as Usual in the China-Myanmar Borderlands Alessandro Rippa, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich Martin Saxer, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich The aim of this project is to lay the conceptual groundwork for a new understanding of the positionality of remote areas around the globe. It rests on the hypothesis that remoteness and connectivity are not independent features but co-constitute each other in particular ways. In the context of this project, Rippa and Saxer conducted exploratory fieldwork together in 2015 along the China-Myanmar border. This collaborative photo essay is one result of their research. They aim to convey an image of Mong La that goes beyond its usual depiction as a place of vice and unruliness, presenting it, instead, as the outcome of a particular China-inspired vision of development. Infamous Mong La It is 6:00 P.M. at the main market of Mong La, the largest town in the small autonomous strip of land on the Chinese border formally known in Myanmar as Special Region 4. A gambler from China’s northern Heilongjiang Province just woke up from a nap. “I’ve been gambling all morning,” he says, “but after a few hours it is better to stop. To rest your brain.” He will go back to the casino after dinner, as he did for the entire month he spent in Mong La. Like him, hundreds of gamblers crowd the market, where open-air restaurants offer food from all over China. A small section of the market is dedicated to Mong La’s most infamous commodity— wildlife. -

MYANMAR DEFENSE COOPERATION to INCREASE ITS INFLUENCE in the INDIAN OCEAN in the CASE of BELT and ROAD INITIATIVE (2013-2017) by Cici Ernasari ID No

THE IMPLEMENTATION OF CHINA’S DEFENSE POLICY IN SINO-MYANMAR DEFENSE COOPERATION TO INCREASE ITS INFLUENCE IN THE INDIAN OCEAN IN THE CASE OF BELT AND ROAD INITIATIVE (2013-2017) By Cici Ernasari ID no. 016201400032 A thesis presented to the Faculty of Humanities President University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Bachelor Degree in International Relations Major in Strategic and Defense Studies 2018 i ii iii iv ABSTRACT Cici Ernasari, International Relations 2014, President University Thesis Title: “The Implementation of China’s Defense Policy in Sino-Myanmar Defense Cooperation to Increase Its Influence in the Indian Ocean in the case of Belt and Road Initiative (2013 – 2017)” The rise of China has been a great phenomenon in the world particularly in this 21st century. This rise has led China becomes the world’s second largest economy and also the world’s largest military. This situation however pushed China to fulfill the increasing demand of energy and to seek for the alternative route. By sharing 2,204 kilometers of its border with China and has direct access to the Indian Ocean, Myanmar becomes a land bridge to get the access to Indian Ocean. Myanmar locates on tri-junction Southeast, South and East Asia and very abundance with natural resources. In the name of Pauk-Phaw, China and Myanmar relations has been existing since the ancient times and both countries have maintained substantive relations. In the context of belt and road initiative, China has implemented its defense policy through the economic and military cooperation with Myanmar. This research therefore explains the implementation of China’s defense policy in Sino-Myanmar defense cooperation to strengthening its position in the Indian Ocean in the context of belt and road initiative from 2013 until 2017. -

Fire and Ice: Conflict and Drugs in Myanmar’S Shan State

Fire and Ice: Conflict and Drugs in Myanmar’s Shan State Asia Report N°299 | 8 January 2019 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 149 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Long Legacy ................................................................................................................... 3 III. A New Drug Dynamic ....................................................................................................... 6 A. A Surge in Production ................................................................................................ 6 B. Tip of the Iceberg ....................................................................................................... 10 IV. The Links Between Drugs and Conflict ............................................................................ 12 A. Current Conflict Dynamics ........................................................................................ 12 B. The Role of the Drug Trade in the Conflict................................................................ 13 C. Ethno-political Clashes, Anti-drug Raids or Bank Heists? ....................................... 15 D. Why Is There Not -

Is the West Driving Myanmar Into the Arms of China? No

ISPSW Strategy Series: Focus on Defense and International Security Issue Is the West driving Myanmar into the arms of China? No. 542 Dr. Norbert Eschborn und Katharina Münster April 2018 Is the West driving Myanmar into the arms of China? Dr Norbert Eschborn Katharina Münster April 2018 Abstract At the start of the Lunar New Year, the Chinese ambassador in Yangon, Myanmar’s largest city, sent out invitations for a New Year’s reception. He praised Myanmar for having maintained political stability and making progress in the peace process. He said that China had played a constructive role in the process and would remain a presence.1 The assembled Burmese ministers, regional dignitaries and parliamentarians must have had mixed feelings upon hearing this. For decades, China has been pursuing ambitious goals in Myanmar, not always to the satisfaction of its neighbour. The West’s policy once again risks increasing Myanmar’s dependence on China. About ISPSW The Institute for Strategic, Political, Security and Economic Consultancy (ISPSW) is a private institute for research and consultancy. The ISPSW is an objective, task-oriented and politically non-partisan institute. In the increasingly complex international environment of globalized economic processes and worldwide political, ecological, social and cultural change, which occasions both major opportunities and risks, decision- makers in the economic and political arena depend more than ever before on the advice of highly qualified experts. ISPSW offers a range of services, including strategic analyses, security consultancy, executive coaching and intercultural competency. ISPSW publications examine a wide range of topics connected with politics, the economy, international relations, and security/ defense. -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved.