Coup in Burma: Implications for Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter on Myanmar to ASEAN and ASEAN Dialogue Partners

Open Letter on Myanmar to ASEAN and ASEAN Dialogue Partners To: ASEAN Leaders H.E. Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Mu’izzaddin Waddaulah, Prime Minister of Brunei H.E Hun Sen, Prime Minister of Cambodia H.E Joko Widodo, President of Indonesia H.E Thongloun Sisoulith, Prime Minister of Laos H.E Tan Sri Muhyiddin Haji Mohd Yassin, Prime Minister of Malaysia H.E Rodrigo Roa Duterte, President of the Philippines H.E Lee Hsien Loong, Prime Minister of Singapore H.E Prayut Chan-o-cha, Prime Minister of Thailand H.E. Nguyen Xuan Phuc, Prime Minister of Vietnam CC: ASEAN Dialogue Partners H.E. Will Nankervis, Ambassador of Australia to ASEAN H.E. Diedrah Kelly, Ambassador of Canada to ASEAN H.E. Deng Xijun, Ambassador of China to ASEAN H.E. Igor Driesmans, Ambassador of the European Union to ASEAN H.E. Shri Jayant N. Khobragade, Ambassador of India to ASEAN H.E. Chiba Akira, Ambassador of Japan to ASEAN H.E. Lim Sungnam, Ambassador of Korea to ASEAN H.E. Pam Dunn, Ambassador of New Zealand to ASEAN H.E. Alexander Ivanov, Ambassador of Russia to ASEAN H.E. Melissa A. Brown, Chargé d’Affaires, a.i., U.S. Mission to ASEAN 4 May 2021 Re: ASEAN's Consensus on Myanmar Your Excellencies, It has been just over a week since a Five-Point Consensus on Myanmar was reached at the ASEAN Leaders’ Meeting on 24 April 2021 between all ASEAN leaders and Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. Although the consensus called for an immediate cessation of violence in Myanmar, there have been at least 18 more killings and 246 more arrests by the junta since. -

Forced to Go East? Iran’S Foreign Policy Outlook and the Role of Russia, China and India Azadeh Zamirirad (Ed.)

Working Paper SWP Working Papers are online publications within the purview of the respective Research Division. Unlike SWP Research Papers and SWP Comments, they are not reviewed by the Institute. MIDDLE EAST AND AFRICA DIVISION | WP NR. 01, APRIL 2020 Forced to Go East? Iran’s Foreign Policy Outlook and the Role of Russia, China and India Azadeh Zamirirad (ed.) Contents Introduction 3 Azadeh Zamirirad Iran’s Energy Industry: Going East? 6 David Ramin Jalilvand Russia: Iran’s Ambivalent Partner 13 Nikolay Kozhanov Iran and China: Ideational Nexus Across the Geography of the BRI 18 Mohammadbagher Forough Indo-Iranian Relations and the Role of External Actors 23 P R Kumaraswamy Opportunities and Challenges in Iran-India Relations 28 Ja’far Haghpanah and Dalileh Rahimi Ashtiani The European Pillar of Iran’s East-West Strategy 33 Sanam Vakil Implications of Tehran’s Look to the East Policy for EU-Iran Relations 38 Cornelius Adebahr 2 Introduction Azadeh Zamirirad The covid-19 outbreak has revived a foreign policy debate in Iran on how much the Dr Azadeh Zamirirad is Dep- country can and should rely on partners like China or Russia. Critics have blamed uty Head of the Middle East and Africa Division at SWP in an overdependence on Beijing for the hesitation of Iranian authorities to halt flights Berlin. from and to China—a decision many believe to have contributed to the severe spread of the virus in the country. Others point to economic necessities given the © Stiftung Wissenschaft drastic sanctions regime that has been imposed on the Islamic Republic by the US und Politik, 2020 All rights reserved. -

Reform in Myanmar: One Year On

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°136 Jakarta/Brussels, 11 April 2012 Reform in Myanmar: One Year On mar hosts the South East Asia Games in 2013 and takes I. OVERVIEW over the chairmanship of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2014. One year into the new semi-civilian government, Myanmar has implemented a wide-ranging set of reforms as it em- Reforming the economy is another major issue. While vital barks on a remarkable top-down transition from five dec- and long overdue, there is a risk that making major policy ades of authoritarian rule. In an address to the nation on 1 changes in a context of unreliable data and weak econom- March 2012 marking his first year in office, President Thein ic institutions could create unintended economic shocks. Sein made clear that the goal was to introduce “genuine Given the high levels of impoverishment and vulnerabil- democracy” and that there was still much more to be done. ity, even a relatively minor shock has the potential to have This ambitious agenda includes further democratic reform, a major impact on livelihoods. At a time when expectations healing bitter wounds of the past, rebuilding the economy are running high, and authoritarian controls on the popu- and ensuring the rule of law, as well as respecting ethnic lation have been loosened, there would be a potential for diversity and equality. The changes are real, but the chal- unrest. lenges are complex and numerous. To consolidate and build on what has been achieved and increase the likeli- A third challenge is consolidating peace in ethnic areas. -

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia Geographically, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are situated in the fastest growing region in the world, positioned alongside the dynamic economies of neighboring China and Thailand. Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia compares the postwar political economies of these three countries in the context of their individual and collective impact on recent efforts at regional integration. Based on research carried out over three decades, Ronald Bruce St John highlights the different paths to reform taken by these countries and the effect this has had on regional plans for economic development. Through its comparative analysis of the reforms implemented by Cam- bodia, Laos and Vietnam over the last 30 years, the book draws attention to parallel themes of continuity and change. St John discusses how these countries have demonstrated related characteristics whilst at the same time making different modifications in order to exploit the strengths of their individual cultures. The book contributes to the contemporary debate over the role of democratic reform in promoting economic devel- opment and provides academics with a unique insight into the political economies of three countries at the heart of Southeast Asia. Ronald Bruce St John earned a Ph.D. in International Relations at the University of Denver before serving as a military intelligence officer in Vietnam. He is now an independent scholar and has published more than 300 books, articles and reviews with a focus on Southeast Asia, -

Burma Holds Peace Conference

CRS INSIGHT Burma Holds Peace Conference September 8, 2016 (IN10566) | Related Author Michael F. Martin | Michael F. Martin, Specialist in Asian Affairs ([email protected], 7-2199) In what many observers hope could be a step toward ending Burma's six-decade long, low-grade civil war and establishing a process eventually leading to reconciliation and possibly the formation of a democratic federated state, over 1,400 representatives of ethnic political parties, ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), the government in Naypyitaw and its military (Tatmadaw), and other concerned parties attended a peace conference in Naypyitaw, Burma, on August 31–September 3, 2016. Convened by Aung San Suu Kyi, State Counsellor for the government in Naypyitaw, the conference was called the "21st Century Panglong Peace Conference," a reference to a similar event convened by Aung San Suu Kyi's father, General Aung San, in 1947 that led to the creation of the independent state of Burma. Aung San Suu Kyi stated that she had hoped the conference would be an initial gathering of all concerned parties to share views for the future of a post-conflict Burma. Progress at the conference appeared to be hampered by the Tatmadaw's objection to inviting three EAOs to the conference, and two other ethnic organizations downgrading their participation. In addition, differences over protocol matters during the conference were perceived by some EAO representatives as deliberate disrespect on the part of the organizers. Statements presented by Commander-in-Chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing and representatives of several EAOs, moreover, indicated a serious gap in their visions of a democratic federated state of Burma and the path to achieving that goal. -

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945- )

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945 - ) Major Events in the Life of a Revolutionary Leader All terms appearing in bold are included in the glossary. 1945 On June 19 in Rangoon (now called Yangon), the capital city of Burma (now called Myanmar), Aung San Suu Kyi was born the third child and only daughter to Aung San, national hero and leader of the Burma Independence Army (BIA) and the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), and Daw Khin Kyi, a nurse at Rangoon General Hospital. Aung San Suu Kyi was born into a country with a complex history of colonial domination that began late in the nineteenth century. After a series of wars between Burma and Great Britain, Burma was conquered by the British and annexed to British India in 1885. At first, the Burmese were afforded few rights and given no political autonomy under the British, but by 1923 Burmese nationals were permitted to hold select government offices. In 1935, the British separated Burma from India, giving the country its own constitution, an elected assembly of Burmese nationals, and some measure of self-governance. In 1941, expansionist ambitions led the Japanese to invade Burma, where they defeated the British and overthrew their colonial administration. While at first the Japanese were welcomed as liberators, under their rule more oppressive policies were instituted than under the British, precipitating resistance from Burmese nationalist groups like the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL). In 1945, Allied forces drove the Japanese out of Burma and Britain resumed control over the country. 1947 Aung San negotiated the full independence of Burma from British control. -

Burma's Long Road to Democracy

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Priscilla Clapp A career officer in the U.S. Foreign Service, Priscilla Clapp served as U.S. chargé d’affaires and chief of mission in Burma (Myanmar) from June 1999 to August 2002. After retiring from the Foreign Service, she has continued to Burma’s Long Road follow events in Burma closely and wrote a paper for the United States Institute of Peace entitled “Building Democracy in Burma,” published on the Institute’s Web site in July 2007 as Working Paper 2. In this Special to Democracy Report, the author draws heavily on her Working Paper to establish the historical context for the Saffron Revolution, explain the persistence of military rule in Burma, Summary and speculate on the country’s prospects for political transition to democracy. For more detail, particularly on • In August and September 2007, nearly twenty years after the 1988 popular uprising the task of building the institutions for stable democracy in Burma, public anger at the government’s economic policies once again spilled in Burma, see Working Paper 2 at www.usip.org. This into the country’s city streets in the form of mass protests. When tens of thousands project was directed by Eugene Martin, and sponsored by of Buddhist monks joined the protests, the military regime reacted with brute force, the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention. beating, killing, and jailing thousands of people. Although the Saffron Revolution was put down, the regime still faces serious opposition and unrest. -

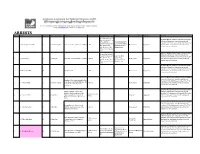

Total Detention, Charge and Fatality Lists

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 25 of the Natural leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Disaster Management Superintendent President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s law, Penal Code - Myint Naing, 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and 505(B), S: 67 of the Dekkhina District regions were also detained. Telecommunications Administrator Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Union Assembly, the President U Win Myint were detained. -

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 8, 2006

Burma Page 1 of 24 2005 Human Rights Report Released | Daily Press Briefing | Other News... Burma Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 8, 2006 Since 1962, Burma, with an estimated population of more than 52 million, has been ruled by a succession of highly authoritarian military regimes dominated by the majority Burman ethnic group. The current controlling military regime, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), led by Senior General Than Shwe, is the country's de facto government, with subordinate Peace and Development Councils ruling by decree at the division, state, city, township, ward, and village levels. In 1990 prodemocracy parties won more than 80 percent of the seats in a generally free and fair parliamentary election, but the junta refused to recognize the results. Twice during the year, the SPDC convened the National Convention (NC) as part of its purported "Seven-Step Road Map to Democracy." The NC, designed to produce a new constitution, excluded the largest opposition parties and did not allow free debate. The military government totally controlled the country's armed forces, excluding a few active insurgent groups. The government's human rights record worsened during the year, and the government continued to commit numerous serious abuses. The following human rights abuses were reported: abridgement of the right to change the government extrajudicial killings, including custodial deaths disappearances rape, torture, and beatings of -

The Taiwan Issue and the Normalization of US-China Relations Richard Bush, Brookings Institution Shelley Rigger, Davidson Colleg

The Taiwan Issue and the Normalization of US-China Relations Richard Bush, Brookings Institution Shelley Rigger, Davidson College The Taiwan Issue in US-China Normalization After 1949, there were many obstacles to normalization of relations between the United States and the new People’s Republic of China (PRC), but Taiwan was no doubt a key obstacle. The Kuomintang-led Republic of China (ROC) government and armies had retreated there. Washington maintained diplomatic relations with the ROC government and, in 1954-55, acceded to Chiang Kai-shek’s entreaties for a mutual defense treaty. After June 1950 with the outbreak of the Korean conflict, the United States took the position that the status of the island of Taiwan— whether it was part of the sovereign territory of China—was “yet to be determined.” More broadly, PRC leaders regarded the United States as a threat to their regime, particularly because of its support for the ROC, and American leaders viewed China as a threat to peace and stability in East Asia and to Taiwan, which they saw as an ally in the containment of Asian communism in general and China in particular. It was from Taiwan’s Ching Chuan Kang (CCK) airbase, for example, that U.S. B-52s flew bombing missions over North Vietnam. By the late 1960s, PRC and U.S. leaders recognized the strategic situation in Asia had changed, and that the geopolitical interests of the two countries were not in fundamental conflict. Jimmy Carter and Deng Xiaoping not only reaffirmed that assessment but also recognized a basis for economic cooperation. -

Violent Repression in Burma: Human Rights and the Global Response

UCLA UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal Title Violent Repression in Burma: Human Rights and the Global Response Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05k6p059 Journal UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal, 10(2) Author Guyon, Rudy Publication Date 1992 DOI 10.5070/P8102021999 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California COMMENTS VIOLENT REPRESSION IN BURMA: HUMAN RIGHTS AND THE GLOBAL RESPONSE Rudy Guyont TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................ 410 I. SLORC AND THE REPRESSION OF THE DEMOCRACY MOVEMENT ....................... 412 A. Burma: A Troubled History ..................... 412 B. The Pro-Democracy Rebellion and the Coup to Restore Military Control ......................... 414 C. Post Coup Elections and Political Repression ..... 417 D. Legalizing Repression ........................... 419 E. A Country Rife with Poverty, Drugs, and War ... 421 II. HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN BURMA ........... 424 A. Murder and Summary Execution ................ 424 B. Systematic Racial Discrimination ................ 425 C. Forced Dislocations ............................. 426 D. Prolonged Arbitrary Detention .................. 426 E. Torture of Prisoners ............................. 427 F . R ape ............................................ 427 G . Portering ....................................... 428 H. Environmental Devastation ...................... 428 III. VIOLATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW ....... 428 A. International Agreements of Burma .............. 429 1. The U.N. -

Time to End the Isolation

Embargoed! PO Box 100 Surrey SM4 9DH ª: +44 (0)780 693 2966 Þ: www.embargoed.org E: [email protected] TIME TO END THE ISOLATION THE UK’S RESPONSIBILITY TO TURKISH CYPRIOTS Prepared and submitted to the Foreign Affairs Committee, House of Commons by Embargoed! on 14 September 2004 TIME TO END THE ISOLATION Embargoed! Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. The Outcome of the Annan Plan Referenda and Implications for 4 Cyprus 3. Ongoing Suffering of the Turkish Cypriot People 7 4. The UK’s Special Responsibility to Turkish Cypriots 10 5. Recommendations: Creating a Positive Dynamic on the Island 11 6. Conclusion 13 7. Notes 14 Page 2 of 15 TIME TO END THE ISOLATION Embargoed! 1. Introduction Embargoed! is an independent pressure group campaigning to bring an immediate and unconditional end to all embargoes against Turkish Cypriots in North Cyprus. Formed in London, where a major concentration of Turkish Cypriots resides, the group welcomes the opportunity to present this submission to the Parliamentary Foreign Affairs Committee. In light of the recent referenda on the Annan Plan and previous legal agreements, we contend that the Greek Cypriot administration, acting under the banner of the ‘Republic of Cyprus’, has neither the right nor the authority to represent the Turkish Cypriot people. For the last 40 years the Turkish Cypriot people have been in a state of isolation for no good reason. Yet the international community has been indifferent to their plight and unwilling to do anything that would fundamentally change the status quo established in Cyprus in December 1963.