Translating the Discourse of Alienation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

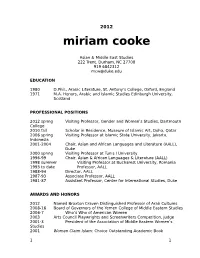

Miriam Cooke

2012 miriam cooke Asian & Middle East Studies 222 Trent, Durham, NC 27708 919 6842312 [email protected] EDUCATION 1980 D.Phil., Arabic Literature, St. Antony's College, Oxford, England 1971 M.A. Honors, Arabic and Islamic Studies Edinburgh University, Scotland PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS 2012 spring Visiting Professor, Gender and Women’s Studies, Dartmouth College 2010 fall Scholar in Residence, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar 2006 spring Visiting Professor at Islamic State University, Jakarta, Indonesia 2001-2004 Chair, Asian and African Languages and Literature (AALL), Duke 2000 spring Visiting Professor at Tunis I University 1996-99 Chair, Asian & African Languages & Literature (AALL) 1998 summer Visiting Professor at Bucharest University, Romania 1993 to date Professor, AALL 1988-94 Director, AALL 1987-93 Associate Professor, AALL 1981-87 Assistant Professor, Center for International Studies, Duke AWARDS AND HONORS 2012 Named Braxton Craven Distinguished Professor of Arab Cultures 2008-16 Board of Governors of the Yemen College of Middle Eastern Studies 2006-7 Who’s Who of American Women 2003 Arts Council Playwrights and Screenwriters Competition, judge 2001-3 President of the Association of Middle Eastern Women’s Studies 2001 Women Claim Islam: Choice Outstanding Academic Book 1 1 2000 Vice-Provost for Interdisciplinary Studies award for Muslim Networks Trent Foundation award for Muslim Networks Workshop (spring 2001) 1997 Women and the War Story Choice Outstanding Academic Book 1995-6 Fulbright Scholarship in Syria - "The Politics of Cultural Production" 1994 North Carolina Humanities Council grant for Genocide Conference 1990 H.F. Guggenheim Consultancy for "Violence and Post-Colonial Islam" Opening the Gates. A Century of Arab Feminist Writing (co-edited with Margot Badran) First Prize: Chicago Women in Publishing Books of Contemporary Relevance Mellon Fellow at Gender and War Institute, Dartmouth College. -

Egypt Under Pressure

EGYPT UNDER PRESSURE A contribution to the understanding of economic, social, and cultural aspects of Egypt today BY Marianne Laanatza Gunvor Mejdell Marina Stagh Kari Vogt Birgitta Wistrand Scandinavian Institute of African Studies Uppsala 1986 TEE IMAGE OF EUROPE IN EGYPTIAN LITERATURE: TWO RECENT SHORT STORIES BY BANW TAHfR ON A RECURRENT THEME, Under the heading "This is the issue" "(trlka kiya al-qadlya) the Egyptian liberal philosopher Zaki Nagib Mahmud summarizes the principal question in Egyptian intellectual debate during the last 150 years in the epitome "what should be our attitude towards the West" (rnsdh: yakcnu mawqifun3 min al-gharb)' 1' The article is provoked by a contribution by Anis Mansur in the daily ~khb&ral-yaurn, in which he relates an encounter between some Egyptian writers, including himself and Ahmad Baha al-Din, and a visiting Russian poet to Egypt in the 1965's. The poet asks them about the issue which Xas most preoccupied Egyptian men of ietters, They were embarrassed by the realization that Egyptian writers (udabz) had no such comnom matter, writes Mansur, After some hesitation they find no better reply thai~!'sccialist . c* .c realism" (a%-ishtir2kiyys ai-wzql lyyaj, Exasperated by s~ch1ac.i. of inslght from some of the leading intellectuals of today, Zak~Kzgib Mahmud strongly asserts that the issue of haw to relate to the West, with all its implications, cnderlies the great controversies in modern Egyptian political and cultural life, He claims that distinctive dividing lines may be drawn all the way between two main tendencies: on the one hand those who reject the West (and all it stands for), on the other hand those who accept Western impulses, provided they are integrated lnto the national cultural tradition. -

Literary Networks and the Making of Egypt's Nineties Generation By

Writing in Cairo: Literary Networks and the Making of Egypt’s Nineties Generation by Nancy Spleth Linthicum A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Near Eastern Studies) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Carol Bardenstein, Chair Associate Professor Samer Ali Professor Anton Shammas Associate Professor Megan Sweeney Nancy Spleth Linthicum [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-9782-0133 © Nancy Spleth Linthicum 2019 Dedication Writing in Cairo is dedicated to my parents, Dorothy and Tom Linthicum, with much love and gratitude for their unwavering encouragement and support. ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my committee for their invaluable advice and insights and for sticking with me throughout the circuitous journey that resulted in this dissertation. It would not have been possible without my chair, Carol Bardenstein, who helped shape the project from its inception. I am particularly grateful for her guidance and encouragement to pursue ideas that others may have found too far afield for a “literature” dissertation, while making sure I did not lose sight of the texts themselves. Anton Shammas, throughout my graduate career, pushed me to new ways of thinking that I could not have reached on my own. Coming from outside the field of Arabic literature, Megan Sweeney provided incisive feedback that ensured I spoke to a broader audience and helped me better frame and articulate my arguments. Samer Ali’s ongoing support and feedback, even before coming to the University of Michigan (UM), likewise was instrumental in bringing this dissertation to fruition. -

Alia Mossallam 200810290

The London School of Economics and Political Science Hikāyāt Sha‛b – Stories of Peoplehood Nasserism, Popular Politics and Songs in Egypt 1956-1973 Alia Mossallam 200810290 A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, November 2012 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,397 words (excluding abstract, table of contents, acknowledgments, bibliography and appendices). Statement of use of third party for editorial help I confirm that parts of my thesis were copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Naira Antoun. 2 Abstract This study explores the popular politics behind the main milestones that shape Nasserist Egypt. The decade leading up to the 1952 revolution was one characterized with a heightened state of popular mobilisation, much of which the Free Officers’ movement capitalized upon. Thus, in focusing on three of the Revolution’s main milestones; the resistance to the tripartite aggression on Port Said (1956), the building of the Aswan High Dam (1960- 1971), and the popular warfare against Israel in Suez (1967-1973), I shed light on the popular struggles behind the events. -

The Role of Social Agents in the Translation Into English of the Novels of Naguib Mahfouz

Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions. If you have discovered material in AURA which is unlawful e.g. breaches copyright, (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please read our Takedown Policy and contact the service immediately The Role of Social Agents in the Translation into English of the Novels of Naguib Mahfouz Vol. 1/2 Linda Ahed Alkhawaja Doctor of Philosophy ASTON UNIVERSITY April, 2014 ©Linda Ahed Alkhawaja, 2014 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. Thesis Summary Aston University The Role of Social Agents in the Translation into English of the Novels of Naguib Mahfouz Linda Ahed Alkhawaja Doctor of Philosophy (by Research) April, 2014 This research investigates the field of translation in an Egyptain context around the work of the Egyptian writer and Nobel Laureate Naguib Mahfouz by adopting Pierre Bourdieu’s sociological framework. Bourdieu’s framework is used to examine the relationship between the field of cultural production and its social agents. The thesis includes investigation in two areas: first, the role of social agents in structuring and restructuring the field of translation, taking Mahfouz’s works as a case study; their role in the production and reception of translations and their practices in the field; and second, the way the field, with its political and socio-cultural factors, has influenced translators’ behaviour and structured their practices. -

The New Egyptian Novel

Map of Greater Cairo sabry hafez THE NEW EGYPTIAN NOVEL Urban Transformation and Narrative Form nce the cultural and political beacon of the Arab world, Cairo is now close to becoming the region’s social sump. The population of this megalopolis has swollen to an estimated 17 million, more than half of whom live in the sprawling self- Obuilt neighbourhoods and shantytowns that ring the ancient heart of the city and its colonial-era quarters. Since the late 1970s, the regime’s lib- eralization policy—infitah, or ‘open door’—combined with the collapse of the developmentalist model, a deepening agrarian crisis and accel- erated rural–urban migration, have produced vast new zones of what the French call ‘mushroom city’. The Arabic term for them al-madun al-‘ashwa’iyyah might be rendered ‘haphazard city’; the root means ‘chance’. These zones developed after the state had abandoned its role as provider of affordable social housing, leaving the field to the private sector, which concentrated on building middle and upper-middle-class accommodation, yielding higher returns. The poor took the matter into their own hands and, as the saying goes, they did it poorly. Sixty per cent of Egypt’s urban expansion over the last thirty years has consisted of ‘haphazard dwellings’. These districts can lack the most basic services, including running water and sewage. Their streets are not wide enough for ambulances or fire engines to enter; in places they are even narrower than the alleyways of the ancient medina. The random juxtaposition of buildings has produced a proliferation of cul-de-sacs, while the lack of planning and shortage of land have ensured a complete absence of green spaces or squares. -

1990-1410H- Yahya Haqqi.Docx

-,+* $("دة ا%$#ذ ﯾﺤﯿﻰ ﺣﻘﻲ &90"56 78"6ة &/,4 12.3 ا0("/.* دب ا0(<8= 0(م 1410ــ/1990م D& AE8 اA.B>0& C+B>0 .اD M+N0 رب اT/")0 واR20' و&L M+NO "PM.$ H,Q :RE0$ل &D إG0& H0س -"3* XB"Y اW,/& K+E0= ا%5U5)0& MVQ C8 D& MVQ >.O وX6"PS M])0& =0 ر7O \.6,\ ازراء ورF>N0& \.6 اG^K0= _NYب اK+E0 _NYب ا90`.,* و&/("0= أ19N0& "]U اAU>W0 إن GfMNU =V,g= أن _NYب &90`1 3= >ه ا70"6ة -"Pا 0KcUن a :A<>$ =3 nENU أMB أن إl "<Z"mPء 7O"راة k,0.< أو ^,ً" E,0+(* أو اGi,0 "ًR7#$"ء، وإK< "+P و3"ءًا PvO_ wN8" اcU>)0* ا0#= أuق 5G/& r8"#- =3 "]iN3 :R$s& "].,Qل &B M0"q0ً" ًُِ" 1Oxy H,Q اKW0ن، A,)0& X,^ H,Q و&/(<H,Q ،*cm/& vk,8 "+]O *3 إJM)0& *O"g وإزا0* ا90وق T8 ا%Glس وا0ان، N,2OS (>90& *O&>- *U"QL H,QS* اvcmQ *O_ ،*Q"+70 اC90 إMB H0 أi+#O r0K0ُ 3= اM8S ،)m0أت أول VG0& >$ 1.,)#0 *0S"NOغ 3= اQ"m,0 v0"gS hC90< اي MU>U أن K8 4.,Q rV,}Uادي r.3 4V->.0 >cVQ واCO MB اaS .C70 ال ا0(,+"ء إK.0& H0: 0S"NUن -m€ $< اVG0غ، أدر-v أHG)O "<>.• 1Vg "ًU اC90 وأJ".~ rP وU rUK+y<اد 8[+" اga#<اب CO اv0"c3 *c.cN0: أhr8e-_ >)m0& ?eQ ور$+v ~.< و$.,* u"G,0 v0"c3 €.ci#,0• O 9N8 4.,Q >)m0& =3"6#= أM)8 H#3 "U 4.,Q Af v.8 €0 ذ40 أن vQ"}#$"3 h"<"EGy >ه ا%XVE8 *O >ه &90`"16 أن B =GVy`"رة _A#P أدرى GO= 8#"رqU[" وأ$+"ء K+u$[" .وأg+"ر>" 3= -1 وع &/(<3* y Mc0(ض yاS €,#,0 "]f&0`." و&X]G0 أc0&S "ًU,.1 اmGP A0S M)8 r)+7P A0 rGO =g"V0ه .S>ا uء NOن Bً" MB Af أن gKy€ ا1BS w3M#0 اM70ب، S$ال S H#O =V,g =3 19GU-.€ وأS CU/"ذا MB .>ا &NPaار، أl >#PاUL"#0& =3 "G6"+,Q CO r8 واN0`"رة QL"EU A],)0ن r8 إ0= G9YS" ان k0& CQ<? أS .*.O"P *O_ "GP>ا -G)U A]3 "G.,Q =,}GU a :Rن أO_ "GP* q#O,9* و&z>7U A,)0 ان O 1- =3`+"ر z>lْ اG70ن CO rfMNU "+8 =0"VU a _<ار k.,8* 1Vc#E+8 18 *.V0"8 اW0<ة &%ر.*. -

A Study in Intertextuality and Religious Identity in Selected Novels of Egyptian Literature

The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences A Study in Intertextuality and Religious Identity in Selected Novels of Egyptian Literature A Thesis Submitted to The Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts By Grace R. McMillan Stoute Under the supervision of Dr. Mona Mikhail May /2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to The Department of Arab & Islamic Civilizations faculty and staff at The American University in Cairo. To my dear professors, Dr. Mona N. Mikhail, Dr. Hussein Hammoudah, Dr. Sayed Fadl, and Dr. Dina Heshmat for their constant guidance and patience throughout this process as well as my overall journey in graduate studies. Special thanks goes to my beloved mother for her love, support, and prayers; and to her friend Dr. Y. Singleton for her encouragement. Lastly, I would like to thank my friends, both in Egypt and abroad, for their undying love and support. Grace R. McMillan Stoute TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction......................................................................................................Page 1 Chapter One: Influences of the Historical on Egypt’s Literary Field……..........................................................................................................Page 5 Chapter Two The Question of Religion in the Era of Mahfouz ...........................................Page 15 Chapter Three: Intertextuality & Portraying Inter-Faith Relations...........................................Page -

The Influence of Egyptian Novel on the Emergence of the First Modern Malaysian Novel Assoc

Saudi Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences ISSN 2415-6256 (Print) Scholars Middle East Publishers ISSN 2415-6248 (Online) Dubai, United Arab Emirates Website: http://scholarsmepub.com/ The Influence of Egyptian Novel on the Emergence of the First Modern Malaysian Novel Assoc. Professor Dr. Rosni B. Samah, Dr. Fariza bt. Puteh-Behak, Assoc. Professor Dr. Zainul Rijal bin Abdul Razak, Dr. Wan Azura bt. Wan Ahmad, Aisyah bt. Ishak Faculty of Major Language, Islamic Science University of Malaysia, Malaysia Abstract: Zainab’ novel written by Al- Haikal was the first novel in modern *Corresponding author Egyptian literature. The theme tells about women's freedom from the shackles of Dr. Rosni B. Samah life traditions. Similar theme is found in Faridah Hanom‟s novel which is Malaysia's first novel, by Syed Syeikh al-Hadi. The plot of Faridah Hanom Article History revolves around the above issue which takes the backdrop of Cairo and its Received: 05.11.2017 surroundings. The current study aims to identify the similarities between Zainab's Accepted: 13.11.2017 novel and Faridah Hanom's novel in terms of themes, characters, plots and Published: 30.11.2017 backgrounds. The comparison and analysis carried out between the two novels clearly indicate that there are similarities in the selection of themes, characters, plot DOI: construction structures and depicted background images. The main theme of both 10.21276/sjhss.2017.2.11.8 novels is freedom of women from the grip of tradition that does not allow women the right to go out to work, to study and to choose a life partner. -

Sufism in the Contemporary Arabic Novel

Sufism in the Contemporary Arabic Novel Ziad Elmarsafy ELMARSAFY 9780748641406 PRINT.indd iii 23/10/2012 17:16 © Ziad Elmarsafy, 2012 Edinburgh University Press Ltd 22 George Square, Edinburgh EH8 9LF www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 11/15 Adobe Garamond by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 4140 6 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 5564 9 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 0 7486 5566 3 (epub) ISBN 978 0 7486 5565 6 (Amazon ebook) The right of Ziad Elmarsafy to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. ELMARSAFY 9780748641406 PRINT.indd iv 23/10/2012 17:16 Contents Series Editor’s Foreword vii Abbreviations x Acknowledgements xi Introduction: Ouverture 1 1 Naguib Mahfouz: (En)chanting Justice 23 2 Tayeb Salih: The Returns of the Saint 52 3 Maªmūd Al-Masʿadī: Witnessing Immortality 66 4 The Survival of Gamal Al-Ghitany 78 5 Ibrahim Al-Koni: Writing and Sacrifice 107 6 Tahar Ouettar: The Saint and the Nightmare of History 139 Epilogue: Bahaa Taher, Solidarity and Idealism 162 Notes 168 Bibliography 235 Index 253 ELMARSAFY 9780748641406 PRINT.indd v 23/10/2012 17:16 ELMARSAFY 9780748641406 PRINT.indd vi 23/10/2012 17:16 Series Editor’s Foreword new and unique series, ‘Edinburgh Studies in Modern Arabic Literature’ A will, it is hoped, fill in a gap in scholarship in the field of modern Arabic literature. -

Town and Country in Modern Arabic Literature

TOWN AND COUNTRY IN MODERN ARABIC LITERATURE by Robin Ostle Dr. Robin Ostle, rapporteur for civilization. Not the least of these the recent UFSI conference on achievements was that of literature, "Town and Country in Modern for in the Islamic period Arabic liter- Arabic Literature," has written a ature has always been bourgeois in the strictly literal sense of the word. UFSI Report summarizing the It depended very much on city discussion. A videotape of a par- cultures for its patronage and appre- ticipants' discussion of the main ciation, finding there those milieux conference themes is also avail- in which it could perform certain able. time-honored functions. Naturally the tensions which sur- round the relations between cities and their hinterlands are in no sense confined to the Near and Middle Ibn Khaldun is the most notable East, either now or at any other time authority to have indicated in a com- in history. But in this area they have plete and convincing manner that always appeared particularly acute. much of the history of the Near and If one drives out of Cairo in the Middle East revolves around the re- direction of the Pyramids one can lationships between urban centers experience a sense of shock at the and their hinterlands.1 lslam itself suddenness of the transition from was born in an urban setting and town to hinterland, and this is only sought subsequently to assert its one example of many. Throughout control over the surrounding desert the region, desert or semidesert fre- environment. The early centuries of quently reach into the very perim- Islamic civilization saw, on the one eters of the middle eastern town. -

Egypt Under Pressure

EGYPT UNDER PRESSURE A contribution to the understanding of economic, social, and cultural aspects of Egypt today BY Marianne Laanatza Gunvor Mejdell Marina Stagh Kari Vogt Birgitta Wistrand Scandinavian Institute of African Studies Uppsala 1986 Published and distributed by The Scandinavian Institute of African Studies P 0 Box 1703 S-751 47 Uppsala, Sweden EGYPT UNDER PRESSURE A contribution to the understanding of economic, social, and cultural aspects of Egypt today BY Marianne Laanatza Gunvor Mejdell Marina Stagh Kari Vogt Birgitta Wistrand Scandinavian Institute of African Studies Uppsala 1986 O The Authors 1986 ISBY 91- 7106 -255-6 Printed in Sweden by The Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, Uppsala 1986 1. EFFORTS TO CHANGE THE DImION OF THE Mrr71P'FWQ EONW - Are they hsed on reality or illusion ?, Mar ianne Laanatza 2. MILITANT ISMIN EGYPT A survey, Kari Voqt 3. RELIGIOUS REVIVAL AND POLITICAL IVIDBTLISATION: Developmt of the Copitic -unity in Egypt, Kari Vogt 4. THE PRESS IN - Hm free is the freedom of speech ?, Marina Stagh 5. THE IMAGE OF EUROPE IN EXXPTIAN LITlFRAm: Tm recent short stories by Baha Tahir on a rearrent the., Gunvor l& jdell 6. TOURISM IN EXXPT - Interclmnge or confrontation, Birgitta Wistrand 7. THE FOLLCW-UP IN M;WF, Mar imeLaanat za The publication pressure is the result of a co-operation between soms Nordic researchers representing different disciplines. In April 1985 a two-day seminar on Egypt took place in Stockholm at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs. A grant covering travelling expenses -was made by the Nordic Co-operation Cammittee for International Politics.