Return of the Spirit a Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miriam Cooke

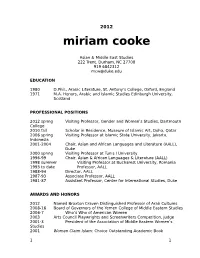

2012 miriam cooke Asian & Middle East Studies 222 Trent, Durham, NC 27708 919 6842312 [email protected] EDUCATION 1980 D.Phil., Arabic Literature, St. Antony's College, Oxford, England 1971 M.A. Honors, Arabic and Islamic Studies Edinburgh University, Scotland PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS 2012 spring Visiting Professor, Gender and Women’s Studies, Dartmouth College 2010 fall Scholar in Residence, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar 2006 spring Visiting Professor at Islamic State University, Jakarta, Indonesia 2001-2004 Chair, Asian and African Languages and Literature (AALL), Duke 2000 spring Visiting Professor at Tunis I University 1996-99 Chair, Asian & African Languages & Literature (AALL) 1998 summer Visiting Professor at Bucharest University, Romania 1993 to date Professor, AALL 1988-94 Director, AALL 1987-93 Associate Professor, AALL 1981-87 Assistant Professor, Center for International Studies, Duke AWARDS AND HONORS 2012 Named Braxton Craven Distinguished Professor of Arab Cultures 2008-16 Board of Governors of the Yemen College of Middle Eastern Studies 2006-7 Who’s Who of American Women 2003 Arts Council Playwrights and Screenwriters Competition, judge 2001-3 President of the Association of Middle Eastern Women’s Studies 2001 Women Claim Islam: Choice Outstanding Academic Book 1 1 2000 Vice-Provost for Interdisciplinary Studies award for Muslim Networks Trent Foundation award for Muslim Networks Workshop (spring 2001) 1997 Women and the War Story Choice Outstanding Academic Book 1995-6 Fulbright Scholarship in Syria - "The Politics of Cultural Production" 1994 North Carolina Humanities Council grant for Genocide Conference 1990 H.F. Guggenheim Consultancy for "Violence and Post-Colonial Islam" Opening the Gates. A Century of Arab Feminist Writing (co-edited with Margot Badran) First Prize: Chicago Women in Publishing Books of Contemporary Relevance Mellon Fellow at Gender and War Institute, Dartmouth College. -

Arabic Language and Literature 1979 - 2018

ARABIC LANGUAGEAND LITERATURE ARABIC LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE 1979 - 2018 ARABIC LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE A Fleeting Glimpse In the name of Allah and praise be unto Him Peace and blessings be upon His Messenger May Allah have mercy on King Faisal He bequeathed a rich humane legacy A great global endeavor An everlasting development enterprise An enlightened guidance He believed that the Ummah advances with knowledge And blossoms by celebrating scholars By appreciating the efforts of achievers In the fields of science and humanities After his passing -May Allah have mercy on his soul- His sons sensed the grand mission They took it upon themselves to embrace the task 6 They established the King Faisal Foundation To serve science and humanity Prince Abdullah Al-Faisal announced The idea of King Faisal Prize They believed in the idea Blessed the move Work started off, serving Islam and Arabic Followed by science and medicine to serve humanity Decades of effort and achievement Getting close to miracles With devotion and dedicated The Prize has been awarded To hundreds of scholars From different parts of the world The Prize has highlighted their works Recognized their achievements Never looking at race or color Nationality or religion This year, here we are Celebrating the Prize›s fortieth anniversary The year of maturity and fulfillment Of an enterprise that has lived on for years Serving humanity, Islam, and Muslims May Allah have mercy on the soul of the leader Al-Faisal The peerless eternal inspirer May Allah save Salman the eminent leader Preserve home of Islam, beacon of guidance. -

Egypt Under Pressure

EGYPT UNDER PRESSURE A contribution to the understanding of economic, social, and cultural aspects of Egypt today BY Marianne Laanatza Gunvor Mejdell Marina Stagh Kari Vogt Birgitta Wistrand Scandinavian Institute of African Studies Uppsala 1986 TEE IMAGE OF EUROPE IN EGYPTIAN LITERATURE: TWO RECENT SHORT STORIES BY BANW TAHfR ON A RECURRENT THEME, Under the heading "This is the issue" "(trlka kiya al-qadlya) the Egyptian liberal philosopher Zaki Nagib Mahmud summarizes the principal question in Egyptian intellectual debate during the last 150 years in the epitome "what should be our attitude towards the West" (rnsdh: yakcnu mawqifun3 min al-gharb)' 1' The article is provoked by a contribution by Anis Mansur in the daily ~khb&ral-yaurn, in which he relates an encounter between some Egyptian writers, including himself and Ahmad Baha al-Din, and a visiting Russian poet to Egypt in the 1965's. The poet asks them about the issue which Xas most preoccupied Egyptian men of ietters, They were embarrassed by the realization that Egyptian writers (udabz) had no such comnom matter, writes Mansur, After some hesitation they find no better reply thai~!'sccialist . c* .c realism" (a%-ishtir2kiyys ai-wzql lyyaj, Exasperated by s~ch1ac.i. of inslght from some of the leading intellectuals of today, Zak~Kzgib Mahmud strongly asserts that the issue of haw to relate to the West, with all its implications, cnderlies the great controversies in modern Egyptian political and cultural life, He claims that distinctive dividing lines may be drawn all the way between two main tendencies: on the one hand those who reject the West (and all it stands for), on the other hand those who accept Western impulses, provided they are integrated lnto the national cultural tradition. -

Literary Networks and the Making of Egypt's Nineties Generation By

Writing in Cairo: Literary Networks and the Making of Egypt’s Nineties Generation by Nancy Spleth Linthicum A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Near Eastern Studies) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Carol Bardenstein, Chair Associate Professor Samer Ali Professor Anton Shammas Associate Professor Megan Sweeney Nancy Spleth Linthicum [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-9782-0133 © Nancy Spleth Linthicum 2019 Dedication Writing in Cairo is dedicated to my parents, Dorothy and Tom Linthicum, with much love and gratitude for their unwavering encouragement and support. ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my committee for their invaluable advice and insights and for sticking with me throughout the circuitous journey that resulted in this dissertation. It would not have been possible without my chair, Carol Bardenstein, who helped shape the project from its inception. I am particularly grateful for her guidance and encouragement to pursue ideas that others may have found too far afield for a “literature” dissertation, while making sure I did not lose sight of the texts themselves. Anton Shammas, throughout my graduate career, pushed me to new ways of thinking that I could not have reached on my own. Coming from outside the field of Arabic literature, Megan Sweeney provided incisive feedback that ensured I spoke to a broader audience and helped me better frame and articulate my arguments. Samer Ali’s ongoing support and feedback, even before coming to the University of Michigan (UM), likewise was instrumental in bringing this dissertation to fruition. -

"The Yacoubian Building" by Alaa Al Aswany, Part 1 Reading in Retirement by Dr

"The Yacoubian Building" by Alaa Al Aswany, Part 1 Reading in Retirement by Dr. Charles S. Grippi This is the first of a three part series. Aswany's "The Yacoubian Building" (Arabic version 2002 and the English translation by Humphrey Davies, New York: Harper Perennial Ed., 2006) is a quite cogent novel in a number of ways. Centered in Cairo, Egypt, the cultural capital of the Muslim world, in the early 1990's, the novel reveals an expansively liberating spirit on subjects that were strictly taboo for publication in a Muslim country and certainly are still anathema in fundamentalist countries of the Muslim world. The novel took Egypt by storm by becoming a best seller in 2002 and 2003 and then being proclaimed the best novel in 2003. To date, the novel has been translated into 23 languages. Made into an "Adults Only" film in 2006, it broke a box office attendance record by earning 6,000,000 Egyptian Pounds the first week and 20,000,000 E.Ps. during its initial theatrical run. In 2006, the film was submitted as Egypt's entry to the 79th Academy Awards "Best Foreign Film Category." In 2006, a television series bearing the same name began: however, frank sexual scenes were omitted. The novel created political controversy by its attacks on the corrupt, undemocratic one party system that has ruled since the country gained its independence with the overthrow of the puppet government of King Farouk that was supported by the British. The revolution allowed Egyptians to rule their own country for the first time in almost 2,500 years harking back to the invasions of the Persians and by the Greek Alexander the Great in the 4th century B.C. -

Alia Mossallam 200810290

The London School of Economics and Political Science Hikāyāt Sha‛b – Stories of Peoplehood Nasserism, Popular Politics and Songs in Egypt 1956-1973 Alia Mossallam 200810290 A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, November 2012 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,397 words (excluding abstract, table of contents, acknowledgments, bibliography and appendices). Statement of use of third party for editorial help I confirm that parts of my thesis were copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Naira Antoun. 2 Abstract This study explores the popular politics behind the main milestones that shape Nasserist Egypt. The decade leading up to the 1952 revolution was one characterized with a heightened state of popular mobilisation, much of which the Free Officers’ movement capitalized upon. Thus, in focusing on three of the Revolution’s main milestones; the resistance to the tripartite aggression on Port Said (1956), the building of the Aswan High Dam (1960- 1971), and the popular warfare against Israel in Suez (1967-1973), I shed light on the popular struggles behind the events. -

Modern Arabic Literature Between the Nation and the World: the Bilingual Singularity of Kahlil Gibran

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online 1 Modern Arabic Literature between the Nation and the World: The Bilingual Singularity of Kahlil Gibran Ghazouane Arslane Queen Mary University of London Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 2 I, Ghazouane Arslane, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Ghazouane Arslane Date: 23/12/2019 3 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................ 4 Note on Translation, -

The Role of Social Agents in the Translation Into English of the Novels of Naguib Mahfouz

Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions. If you have discovered material in AURA which is unlawful e.g. breaches copyright, (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please read our Takedown Policy and contact the service immediately The Role of Social Agents in the Translation into English of the Novels of Naguib Mahfouz Vol. 1/2 Linda Ahed Alkhawaja Doctor of Philosophy ASTON UNIVERSITY April, 2014 ©Linda Ahed Alkhawaja, 2014 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. Thesis Summary Aston University The Role of Social Agents in the Translation into English of the Novels of Naguib Mahfouz Linda Ahed Alkhawaja Doctor of Philosophy (by Research) April, 2014 This research investigates the field of translation in an Egyptain context around the work of the Egyptian writer and Nobel Laureate Naguib Mahfouz by adopting Pierre Bourdieu’s sociological framework. Bourdieu’s framework is used to examine the relationship between the field of cultural production and its social agents. The thesis includes investigation in two areas: first, the role of social agents in structuring and restructuring the field of translation, taking Mahfouz’s works as a case study; their role in the production and reception of translations and their practices in the field; and second, the way the field, with its political and socio-cultural factors, has influenced translators’ behaviour and structured their practices. -

Nowe Strategie Liryczne Współczesnej Poezji Egipskiej Twórczość Poetów

Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu Wydział Neofilologii Katedra Studiów Azjatyckich Zakład Arabistyki i Islamistyki Agnieszka Piotrowska Nowe strategie liryczne współczesnej poezji egipskiej Twórczość poetów pokolenia lat 90. Praca doktorska napisana pod kierunkiem prof. dr hab. Adnana Abbasa Poznań 2010 1 Dla M. i H. 2 Poezja nie jest czymś, co można osiągnąć tylko u Malindi. Można ją znaleźć w każdym kraju. Przysłowie mówi To, co jest na Pembie, jest równie dobrze na Zanzibarze – odrzuć Pembę i Zanzibar i powiedz: co jest w Europie, jest także i w Afryce; odrzuć Europę i powiedz: co jest w Afryce, jest także w Azji, odrzuć Afrykę i powiedz: co jest w Azji, jest też w Ameryce; odrzuć Azję i powiedz: co jest w Ameryce , jest i w Australii – świat twórczości podobny jest w narodach wszystkich ludzkich istot; ukazuje ich wspólne pochodzenie i wielką jedność. Shaaban Robert (w: Wanda Leopold, O literaturze Czarnej Afryki) 3 SPIS TREŚCI WSTĘP 7 ROZDZIAŁ 1 17 Poezja egipska od okresu odrodzenia (druga połowa XIX wieku-początek XX wieku) do początku XXI wieku: Zarys 1.1. Poezja egipska czas i rozwój 18 1.1.1. Poezja do lat 50. XX wieku 18 1.1.2. Poezja okresu modernizmu 20 1.1.3. Poezja ostatnich dziesięcioleci (od lat 80. do dziś) 24 1.2. Czym jest poezja pokolenia lat 90.? Wprowadzenie do tematu 27 ROZDZIAŁ 2 Tło historyczne i sytuacja aktualna a nowa grupa poetycka lat 90 31 2.1. Sytuacja społeczna i kulturalna Egiptu (lata 90. XX wieku - początek XXI wieku) 31 2.2. Charakterystyka nowej grupy poetyckiej. Przyczyny jej powstania 40 2.3. -

Thesis Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree Of

Modern Arabic Literary Biography: A study of character portrayal in the works of Egyptian biographers of the first half of the Twentieth Century, with special reference to literary biography BY WAHEED MOHAMED AWAD MOWAFY Thesissubmitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds The Department of Arabic and Middle Eastern Studies June 1999 I confirm that the work submitt&d is my own and that appropriate credit has been given where referenceshave been made to the work of others ACKNONNILEDGEMENTS During the period of this study I have received support and assistýncefrom a number of people. First I would like to expressmy sincere gratitude and appreciation to my supervisor Dr. A. Shiviiel, who guided me throughout this study with encouragement, patience and support. His generoushelp was always there whenever neededand he undoubtedly easedmy task. I also acknowledgemy indebtednessto the Faculty of Da*ral-ýJlýrn, Cairo University, PP) OW Op 4t or and in particular to Profs. Raja Jabr and al-Tahir Ahmed Makki and Abd al-Sabur 000 SIýZin for inspiring me in my study of Arabic Literature. Next I would like to thank the Egyptian EducationBureau and in particular the Cultural Counsellorsfor their support. I also wish to expressmy gratitudeto Prof Atiyya Amir of Stockholm University, Prof. C Ob 9 Muhammad Abd al-Halim of S. 0. A. S., London University, Prof. lbrlfrim Abd al- C Rahmaonof Ain ShamsUniversity, Dr. Muhammad Slim Makki"and Mr. W. Aziz for 0V their unlimited assistance. 07 Finally, I would like to thank Mr. A. al-Rais for designing the cover of the thesis, Mr. -

Alaa Al-Aswany Calls Upon the UN V3

PRESS RELEASE Paris, April 8, 2019 Alaa al-Aswany, author of the « Yacoubian Building », calls upon the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and the protection of freedom of expression to end persecution against him. François Zimeray, Matthias Fekl and Jessica Finelle submitted an allegation letter to the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of freedom of expression to decry Alaa al-Aswany’s fate in Egypt. Banned from publishing his books for the past 5 years, Alaa al-Aswany is being prosecuted since March 14, 2019 by the Egyptian Military Prosecutor for "insulting the President of the Republic, the armed forces and judicial institutions". The Military Prosecutor's Office's accusations are based on the content of his latest book, The Republic As If, as well as on his articles published in Deutsche Welle Arabic. Alaa Al-Aswany can no longer travel to Egypt without being arrested and brought before the Egyptian military judge for having exercised his freedom of expression and opinion. He also fears the fate of his family members, all living in Egypt. In the allegation letter to the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of freedom of expression in Geneva, François Zimeray, Jessica Finelle and Matthias Fekl denounced the flagrant violation of a fundamental right, such as freedom of expression and opinion, by the Egyptian authorities. According to François Zimeray, "the hopes raised during the Egyptian spring have died, these prosecutions are like a sarcophagus of freedoms ». The criminal proceedings against Alaa al-Aswany are « only a disguised means of intimidating the writer and depriving the Egyptian people of Alaa al- Aswany’s fierce and modern prose ». -

Whose Golden Age?

REVIEWS Alaa Al Aswany, On the State of Egypt: What Caused the Revolution Canongate: Edinburgh 2011, £12.99, paperback 192 pp, 978 0 85786 215 0 Hazem Kandil WHOSE GOLDEN AGE? Revolution is, in essence, a rejection of our dismal reality for one that is entirely divorced from it. The more viable this desired reality appears to us, the more likely we are to pursue it. And how much more viable would this new reality seem if it had in fact existed before? Revolutionary zeal, in this case, feeds on two of the most penetrating human passions: dreaming of a better future, and longing for a once glorious past. Unfortunately, not every ideological movement has recourse to this inspiring mix. In Egypt, and across the Muslim world, Islamists had so far monopolized the power of nostalgia. When preaching about the future, they enticed their audience with recurrent references to an age that actually existed, the time of Prophet Muhammad and his Rightly Guided successors, a time of prosperity, justice, and predominance. Leftists and nationalists, mostly ashamed of what they have contributed to their post-colonial societies, could not claim the same privilege; their ideal realities, they admit, remain unborn. Liberals were even worse off: their past was a disgrace. What Egyptians, in particular, knew about the decades preceding the 1952 coup was what their schoolbooks told them: it was a time of moral and political degeneration; democracy was a sham; peasants were flogged by evil landlords; social disparities were ram- pant; and the country was ruled by an indolent, childlike sovereign, living contentedly under the shadow of British colonialism.