Nasser in the Egyptian Imaginary Omar Khalifah Submitted in Partial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

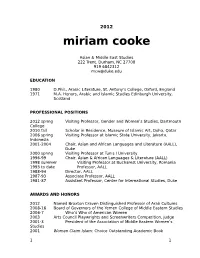

Miriam Cooke

2012 miriam cooke Asian & Middle East Studies 222 Trent, Durham, NC 27708 919 6842312 [email protected] EDUCATION 1980 D.Phil., Arabic Literature, St. Antony's College, Oxford, England 1971 M.A. Honors, Arabic and Islamic Studies Edinburgh University, Scotland PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS 2012 spring Visiting Professor, Gender and Women’s Studies, Dartmouth College 2010 fall Scholar in Residence, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar 2006 spring Visiting Professor at Islamic State University, Jakarta, Indonesia 2001-2004 Chair, Asian and African Languages and Literature (AALL), Duke 2000 spring Visiting Professor at Tunis I University 1996-99 Chair, Asian & African Languages & Literature (AALL) 1998 summer Visiting Professor at Bucharest University, Romania 1993 to date Professor, AALL 1988-94 Director, AALL 1987-93 Associate Professor, AALL 1981-87 Assistant Professor, Center for International Studies, Duke AWARDS AND HONORS 2012 Named Braxton Craven Distinguished Professor of Arab Cultures 2008-16 Board of Governors of the Yemen College of Middle Eastern Studies 2006-7 Who’s Who of American Women 2003 Arts Council Playwrights and Screenwriters Competition, judge 2001-3 President of the Association of Middle Eastern Women’s Studies 2001 Women Claim Islam: Choice Outstanding Academic Book 1 1 2000 Vice-Provost for Interdisciplinary Studies award for Muslim Networks Trent Foundation award for Muslim Networks Workshop (spring 2001) 1997 Women and the War Story Choice Outstanding Academic Book 1995-6 Fulbright Scholarship in Syria - "The Politics of Cultural Production" 1994 North Carolina Humanities Council grant for Genocide Conference 1990 H.F. Guggenheim Consultancy for "Violence and Post-Colonial Islam" Opening the Gates. A Century of Arab Feminist Writing (co-edited with Margot Badran) First Prize: Chicago Women in Publishing Books of Contemporary Relevance Mellon Fellow at Gender and War Institute, Dartmouth College. -

4Th SWYAA Guidebook.Pdf

Contents I. SWYAA Global Assembly ............................................... 4 Purpose ......................................................................................................... 4 Theme ........................................................................................................... 4 Outline .......................................................................................................... 4 Host ............................................................................................................... 5 Participating Countries: ................................................................................... 6 Program ......................................................................................................... 7 Optional Tour ................................................................................................. 8 II. Useful Information ....................................................... 9 General instructions ....................................................................................... 9 Weather ........................................................................................................ 9 Transport in Cairo ........................................................................................... 9 Internet Access ............................................................................................. 10 Laundry services ........................................................................................... 10 Delivery services .......................................................................................... -

Sternfeld-Dissertation-2014

Copyright by Rachel Anne Sternfeld 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Rachel Anne Sternfeld Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Political Coalitions and Media Policy: A Study of Egyptian Newspapers Committee: Jason Brownlee, Supervisor Zachary Elkins Robert Moser Daniel Brinks Esther Raizen Political Coalitions and Media Policy: A Study of Egyptian Newspapers by Rachel Anne Sternfeld, B.A.; M.S.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2014 Dedication For Robert, who challenged us to contemplate difficult questions. Acknowledgements My dissertation would not be possible without the financial, intellectual and emotional support from myriad groups and individuals. The following are simply the highlights and not an exhaustive list of the thanks that are due. I am indebted to various entities at the University of Texas for providing the funding necessary for my graduate work. The Department of Government provided support for my coursework, awarded me a McDonald Fellowship that supported six months of fieldwork, and trusted me to instruct undergraduates as I wrote the dissertation. The Center for Middle Eastern Studies awarded me FLAS grants that covered two years of coursework and sent me to Damascus in the summers of 2008 and 2010. Beyond the University of Texas, the Center for Arabic Study Abroad (CASA) enabled me to spend a full calendar year in Cairo advancing my Arabic skills so I could conduct research without a translator. -

Egypt Under Pressure

EGYPT UNDER PRESSURE A contribution to the understanding of economic, social, and cultural aspects of Egypt today BY Marianne Laanatza Gunvor Mejdell Marina Stagh Kari Vogt Birgitta Wistrand Scandinavian Institute of African Studies Uppsala 1986 TEE IMAGE OF EUROPE IN EGYPTIAN LITERATURE: TWO RECENT SHORT STORIES BY BANW TAHfR ON A RECURRENT THEME, Under the heading "This is the issue" "(trlka kiya al-qadlya) the Egyptian liberal philosopher Zaki Nagib Mahmud summarizes the principal question in Egyptian intellectual debate during the last 150 years in the epitome "what should be our attitude towards the West" (rnsdh: yakcnu mawqifun3 min al-gharb)' 1' The article is provoked by a contribution by Anis Mansur in the daily ~khb&ral-yaurn, in which he relates an encounter between some Egyptian writers, including himself and Ahmad Baha al-Din, and a visiting Russian poet to Egypt in the 1965's. The poet asks them about the issue which Xas most preoccupied Egyptian men of ietters, They were embarrassed by the realization that Egyptian writers (udabz) had no such comnom matter, writes Mansur, After some hesitation they find no better reply thai~!'sccialist . c* .c realism" (a%-ishtir2kiyys ai-wzql lyyaj, Exasperated by s~ch1ac.i. of inslght from some of the leading intellectuals of today, Zak~Kzgib Mahmud strongly asserts that the issue of haw to relate to the West, with all its implications, cnderlies the great controversies in modern Egyptian political and cultural life, He claims that distinctive dividing lines may be drawn all the way between two main tendencies: on the one hand those who reject the West (and all it stands for), on the other hand those who accept Western impulses, provided they are integrated lnto the national cultural tradition. -

Rethinking U.S. Economic Aid to Egypt

Rethinking U.S. Economic Aid to Egypt Amy Hawthorne OCTOBER 2016 RETHINKING U.S. ECONOMIC AID TO EGYPT Amy Hawthorne OCTOBER 2016 © 2016 Project on Middle East Democracy. All rights reserved. The Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit, Washington, D.C. based 501(c)(3) organization. The views represented here do not necessarily reflect the views of POMED, its staff, or its Board members. Limited print copies are also available. Project on Middle East Democracy 1730 Rhode Island Avenue NW, Suite 617 Washington DC 20036 www.pomed.org CONTENTS I. Introduction. 2 II. Background . .4 III. The Bilateral Economic Aid Program: Understanding the Basics. 16 IV. Why Has U.S. Economic Aid Not Had A Greater Positive Impact? . 18 V. The Way Forward . 29 VI. Conclusion . 34 PROJECT ON MIDDLE EAST DEMOCRACY 1 RETHINKING U.S. ECONOMIC AID TO EGYPT I. INTRODUCTION Among the many challenges facing the next U.S. administration in the Middle East will be to forge an effective approach toward Egypt. The years following the 2011 popular uprising that overthrew longtime U.S. ally President Hosni Mubarak have witnessed significant friction with Egypt over issues ranging from democracy and human rights, to how each country defines terrorism (Egypt’s definition encompasses peaceful political activity as well as violent actions), to post-Qaddafi Libya, widening a rift between the two countries that began at least a decade ago. Unless the policies of the current Egyptian government shift, the United States can only seek to manage, not repair, this rift. The next U.S. -

Impassive Modernism in Arabic and Hebrew Literatures

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Against the Flow: Impassive Modernism in Arabic and Hebrew Literatures A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Shir Alon 2017 © Copyright by Shir Alon 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Against the Flow: Impassive Modernism in Arabic and Hebrew Literatures by Shir Alon Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Gil Hochberg, Co-Chair Professor Nouri Gana, Co-Chair Against the Flow: Impassive Modernism in Arabic and Hebrew Literatures elaborates two interventions in contemporary studies of Middle Eastern Literatures, Global Modernisms, and Comparative Literature: First, the dissertation elaborates a comparative framework to read twentieth century Arabic and Hebrew literatures side by side and in conversation, as two literary cultures sharing, beyond a contemporary reality of enmity and separation, a narrative of transition to modernity. The works analyzed in the dissertation, hailing from Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, Egypt, and Tunisia, emerge against the Hebrew and Arabic cultural and national renaissance movements, and the establishment of modern independent states in the Middle East. The dissertation stages encounters between Arabic and Hebrew literary works, exploring the ii parallel literary forms they develop in response to shared temporal narratives of a modernity outlined elsewhere and already, and in negotiation with Orientalist legacies. Secondly, the dissertation develops a generic-formal framework to address the proliferation of static and decadent texts emerging in a cultural landscape of national revival and its aftermaths, which I name impassive modernism. Viewed against modernism’s emphatic features, impassive modernism is characterized by affective and formal investment in stasis, immobility, or immutability: suspension in space or time and a desire for nonproductivity. -

Literary Networks and the Making of Egypt's Nineties Generation By

Writing in Cairo: Literary Networks and the Making of Egypt’s Nineties Generation by Nancy Spleth Linthicum A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Near Eastern Studies) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Carol Bardenstein, Chair Associate Professor Samer Ali Professor Anton Shammas Associate Professor Megan Sweeney Nancy Spleth Linthicum [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-9782-0133 © Nancy Spleth Linthicum 2019 Dedication Writing in Cairo is dedicated to my parents, Dorothy and Tom Linthicum, with much love and gratitude for their unwavering encouragement and support. ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my committee for their invaluable advice and insights and for sticking with me throughout the circuitous journey that resulted in this dissertation. It would not have been possible without my chair, Carol Bardenstein, who helped shape the project from its inception. I am particularly grateful for her guidance and encouragement to pursue ideas that others may have found too far afield for a “literature” dissertation, while making sure I did not lose sight of the texts themselves. Anton Shammas, throughout my graduate career, pushed me to new ways of thinking that I could not have reached on my own. Coming from outside the field of Arabic literature, Megan Sweeney provided incisive feedback that ensured I spoke to a broader audience and helped me better frame and articulate my arguments. Samer Ali’s ongoing support and feedback, even before coming to the University of Michigan (UM), likewise was instrumental in bringing this dissertation to fruition. -

What Inflamed the Iraq War?

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Fellowship Paper, University of Oxford What Inflamed The Iraq War? The Perspectives of American Cartoonists By Rania M.R. Saleh Hilary Term 2008 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my deepest appreciation to the Heikal Foundation for Arab Journalism, particularly to its founder, Mr. Mohamed Hassanein Heikal. His support and encouragement made this study come true. Also, special thanks go to Hani Shukrallah, executive director, and Nora Koloyan, for their time and patience. I would like also to give my sincere thanks to Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, particularly to its director Dr Sarmila Bose. My warm gratitude goes to Trevor Mostyn, senior advisor, for his time and for his generous help and encouragement, and to Reuter's administrators, Kate and Tori. Special acknowledgement goes to my academic supervisor, Dr. Eduardo Posada Carbo for his general guidance and helpful suggestions and to my specialist supervisor, Dr. Walter Armbrust, for his valuable advice and information. I would like also to thank Professor Avi Shlaim, for his articles on the Middle East and for his concern. Special thanks go to the staff members of the Middle East Center for hosting our (Heikal fellows) final presentation and for their fruitful feedback. My sincere appreciation and gratitude go to my mother for her continuous support, understanding and encouragement, and to all my friends, particularly, Amina Zaghloul and Amr Okasha for telling me about this fellowship program and for their support. Many thanks are to John Kelley for sharing with me information and thoughts on American newspapers with more focus on the Washington Post . -

Rethinking Islamist Politics February 11, 2014 Contents

POMEPS STUDIES 6 islam in a changing middle east Rethinking Islamist Politics February 11, 2014 Contents The Debacle of Orthodox Islamism . 7 Khalil al-Anani, Middle East Institute Understanding the Ideological Drivers Pushing Youth Toward Violence in Post-Coup Egypt . 9 Mokhtar Awad, Center for American Progress Why do Islamists Provide Social Services? . 13 Steven Brooke, University of Texas at Austin Rethinking Post-Islamism and the Study of Changes in Islamist Ideology . 16 By Michaelle Browers, Wake Forest University The Brotherhood Withdraws Into Itself . 19 Nathan J. Brown, George Washington University Were the Islamists Wrong-Footed by the Arab Spring? . 24 François Burgat, CNRS, Institut de recherches et d’études sur le monde arabe et musulman (translated by Patrick Hutchinson) Jihadism: Seven Assumptions Shaken by the Arab Spring . 28 Thomas Hegghammer, Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI) The Islamist Appeal to Quranic Authority . 31 Bruce B. Lawrence, Duke University Is the Post-Islamism Thesis Still Valid? . 33 Peter Mandaville, George Mason University Did We Get the Muslim Brotherhood Wrong? . 37 Marc Lynch, George Washington University Rethinking Political Islam? Think Again . 40 Tarek Masoud, Harvard University Islamist Movements and the Political After the Arab Uprisings . 44 Roel Meijer, Radboud University Nijmegen, The Netherlands, and Ghent University, Belgium Beyond Islamist Groups . 47 Jillian Schwedler, Hunter College, City University of New York The Shifting Legitimization of Democracy and Elections: . 50 Joas Wagemakers, Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands Rethinking Islamist Politics . 52 Carrie Rosefsky Wickham, Emory University Progressive Problemshift or Paradigmatic Degeneration? . 56 Stacey Philbrick Yadav, Hobart and William Smith Colleges Online Article Index Please see http://pomeps.org/2014/01/rethinking-islamist-politics-conference/ for online versions of all of the articles in this briefing . -

Faten Hamama and the 'Egyptian Difference' in Film Madamasr.Com January 20

Faten Hamama and the 'Egyptian difference' in film madamasr.com January 20 In 1963, Faten Hamama made her one and only Hollywood film. Entitled Cairo, the movie was a remake of The Asphalt Jungle, but refashioned in an Egyptian setting. In retrospect, there is little remarkable about the film but for Hamama’s appearance alongside stars such as George Sanders and Richard Johnson. Indeed, copies are extremely difficult to track down: Among the only ways to watch the movie is to catch one of the rare screenings scheduled by cable and satellite network Turner Classic Movies. However, Hamama’s foray into Hollywood is interesting by comparison with the films she was making in “the Hollywood on the Nile” at the time. The next year, one of the great classics of Hamama’s career, Al-Bab al-Maftuh (The Open Door), Henri Barakat’s adaptation of Latifa al-Zayyat’s novel, hit Egyptian screens. In stark contrast to Cairo, in which she played a relatively minor role, Hamama occupied the top of the bill for The Open Door, as was the case with practically all the films she was making by that time. One could hardly expect an Egyptian actress of the 1960s to catapult to Hollywood stardom in her first appearance before an English-speaking audience, although her husband Omar Sharif’s example no doubt weighed upon her. Rather, what I find interesting in setting 1963’s Cairo alongside 1964’s The Open Door is the way in which the Hollywood film marginalizes the principal woman among the film’s characters, while the Egyptian film sets that character well above all male counterparts. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian Urban Exigencies: Space, Governance and Structures of Meaning in a Globalising Cairo A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Global Studies by Roberta Duffield Committee in charge: Professor Paul Amar, Chair Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse Assistant Professor Javiera Barandiarán Associate Professor Juan Campo June 2019 The thesis of Roberta Duffield is approved. ____________________________________________ Paul Amar, Committee Chair ____________________________________________ Jan Nederveen Pieterse ____________________________________________ Javiera Barandiarán ____________________________________________ Juan Campo June 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis committee at the University of California, Santa Barbara whose valuable direction, comments and advice informed this work: Professor Paul Amar, Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse, Professor Javiera Barandiarán and Professor Juan Campo, alongside the rest of the faculty and staff of UCSB’s Global Studies Department. Without their tireless work to promote the field of Global Studies and committed support for their students I would not have been able to complete this degree. I am also eternally grateful for the intellectual camaraderie and unending solidarity of my UCSB colleagues who helped me navigate Californian graduate school and come out the other side: Brett Aho, Amy Fallas, Tina Guirguis, Taylor Horton, Miguel Fuentes Carreño, Lena Köpell, Ashkon Molaei, Asutay Ozmen, Jonas Richter, Eugene Riordan, Luka Šterić, Heather Snay and Leila Zonouzi. I would especially also like to thank my friends in Cairo whose infinite humour, loyalty and love created the best dysfunctional family away from home I could ever ask for and encouraged me to enroll in graduate studies and complete this thesis: Miriam Afifiy, Eman El-Sherbiny, Felix Fallon, Peter Holslin, Emily Hudson, Raïs Jamodien and Thomas Pinney. -

Alia Mossallam 200810290

The London School of Economics and Political Science Hikāyāt Sha‛b – Stories of Peoplehood Nasserism, Popular Politics and Songs in Egypt 1956-1973 Alia Mossallam 200810290 A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, November 2012 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,397 words (excluding abstract, table of contents, acknowledgments, bibliography and appendices). Statement of use of third party for editorial help I confirm that parts of my thesis were copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Naira Antoun. 2 Abstract This study explores the popular politics behind the main milestones that shape Nasserist Egypt. The decade leading up to the 1952 revolution was one characterized with a heightened state of popular mobilisation, much of which the Free Officers’ movement capitalized upon. Thus, in focusing on three of the Revolution’s main milestones; the resistance to the tripartite aggression on Port Said (1956), the building of the Aswan High Dam (1960- 1971), and the popular warfare against Israel in Suez (1967-1973), I shed light on the popular struggles behind the events.