Contents List of Tables

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Organic Trade Association's Report

GO TO MARKET REPORT: South Korea The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Foreign Agriculture Service (FAS) provided funding for these reports through the Organic Trade Association’s Organic Export Program Organic Trade Association (OTA) does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation or marital/family status. Persons with disabilities, who require alternative means for communication of program information, should contact OTA. TABLE OF CONTENTS: 1!OVERVIEW 1!REGULATORY STATUS GO TO MARKET REPORT: 2!COMMONLY IMPORTED PRODUCTS South Korea 3!MARKET SECTOR OVERVIEWS 9!MARKET ACCESS AND DISTRIBUTION CHAIN 10!CHARACTERISTICS OF SHOPPERS 12!RESOURCES 13!REFERENCES Overview: The Republic of Korea (formerly South Korea) imports approximately 60 to 70 percent of its food and agricultural products, and is one of the least self-su!cient countries for grain production. Between 2010 and 2015, total spending on food is expected to increase over 20 percent. With over 50 percent of the population concentrated within a 60 mile radius of the capital city of Seoul, that region accounts for over 70 percent of the retail spending in the country. Despite the limited volume of domestic agriculture, Koreans favor locally grown and manufactured foods and are willing to pay a premium for domestic goods. A wide variety of agricultural products are grown or processed locally, including rice, fresh and processed vegetables, fruits, seafood and meats, eggs, dairy products, noodles, sauces, oils, grain "our, beverages, snacks, confections, and liquor. Unlike other sectors of the Korean economy, there is not a focus on exporting in Korean agriculture, and, in general, government policies favor domestic agriculture. -

Collection 2016 - 2017

COLLECTION 2016 - 2017 1 L’Univers Galler De Wereld van Galler The Galler Universe INVITATION À UNE UITNODIGING TOT INVITATION TO A GOURMET RENCONTRE GOURMANDE EEN OVERHEERLIJKE ENCOUNTER WITH GALLER AVEC LES CHOCOLATS ONTMOETING MET DE CHOCOLATES GALLER CHOCOLADES VAN GALLER Jean Galler, artisan chocolatier Jean Galler, chocolatier en auteur Jean Galler, artisan chocolatier et auteur des rencontres les plus van de meest gedurfde en lekkere and the man behind the most audacieuses et gourmandes… ontmoetingen… audacious gourmet encounters… où les meilleurs fourrages waar de beste vullingen zich where the best fillings are s’entourent du meilleur chocolat, hullen in de beste chocolade, coated with the best chocolate, où la sélection des meilleurs waar de keuze voor de beste where the selection of the best ingrédients règne en maître, où ingrediënten onmiskenbaar primeert, ingredients is the top priority, qualité et éthique ne sont pas de waar kwaliteit en ethiek geen where quality and ethics are not vains mots. holle woorden zijn. empty promises. Des recettes toujours meilleures, Steeds verfijndere recepten zonder Ever-exciting recipes that contain sans conservateurs, sans huile de bewaarmiddelen en zonder palmolie, no preserving agents, no palm oil palme, avec de moins en moins de waarin alsmaar minder suiker and less and less sugar, that only sucre et réalisées exclusivement gebruikt wordt en die uitsluitend include natural flavourings for avec des saveurs naturelles pour opgebouwd zijn rond natuurlijke ever more flavour. toujours plus -

Chocolatiers and Chocolate Experiences in Flanders & Brussels

Inspiration guide for trade Chocolatiers and Chocolate Experiences IN FLANDERS & BRUSSELS 1 We are not a country of chocolate. We are a country of chocolatiers. And chocolate experiences. INTRODUCTION Belgian chocolatiers are famous and appreciated the world over for their excellent craftmanship and sense of innovation. What makes Belgian chocolatiers so special? Where can visitors buy a box of genuine pralines to delight their friends and family when they go back home? Where can chocolate lovers go for a chocolate experience like a workshop, a tasting or pairing? Every day, people ask VISITFLANDERS in Belgium and abroad these questions and many more. To answer the most frequently asked questions, we have produced this brochure. It covers all the main aspects of chocolate and chocolate experiences in Flanders and Brussels. 2 Discover Flanders ................................................. 4 Chocolatiers and shops .........................................7 Chocolate museums ........................................... 33 Chocolate experiences: > Chocolate demonstrations (with tastings) .. 39 > Chocolate workshops ................................... 43 > Chocolate tastings ........................................ 49 > Chocolate pairings ........................................ 53 Chocolate events ................................................ 56 Tearooms, cafés and bars .................................. 59 Guided chocolate walks ..................................... 65 Incoming operators and DMC‘s at your disposal .................................74 -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

Asian Cities Report Seoul Retail 2H 2017

Asian Cities Report | Seoul Retail Savills World Research2H 2017 Korea Asian Cities Report Seoul Retail 2H 2017 savills.com.hk/research savills.com.hk/research 01 Asian Cities Report | Seoul Retail 2H 2017 GRAPH 1 First floor retail rents continuing growth of e-commerce. First floor rental increases in major Seoul Based on the Korea Appraisal Supported by the Korea Sale Fiesta (a nationwide government-sponsored retail districts, 2014−2016 Board (KAB) data in June 2017, 1/F rents in the top five retail areas for bargain sales period) and other events, 2014 2015 2016 mid-size buildings have shown a the sales of large discount stores, 5% divergent performance. Retail rents including duty-free shops and outlets, in Myeongdong and Gangnamdaero rose by 9%. In 1H/2017, convenience 4% recorded steady growth from 2014 to store and non-store retail sales continued their double digit growth. 3% mid 2016, but have recorded slight downward movement since 2016. 2% Meanwhile retail rents for Hongdae- Non-store retail Hapjung increased due to new Non-store retail volumes rose by 16% 1% recreational facilities and improved year-on-year (YoY) in 2016 and 13% infrastructure. in 1H/2017. Sales increases in food, 0% electronics and apparel contributed Average contracted rents in to the growth. The sales volumes -1% Myeongdong Gangnamdaero Garosugil Hongdae- Itaewon Myeongdong at the end of June were of online shopping malls operated Hapjung the highest in the city, according to by offline based retailers such as Shinsegae and Lotte group grew far Source: Korea Appraisal Board (KAB) KAB. Myeongdong is an extremely popular foreign tourist destination more rapidly than pure online shopping and attracts significant foot traffic, malls. -

Galler Assortment of 5 Chocolate Bars with Alcohol Filling

Galler Assortment of 5 Chocolate Bars with Alcohol Filling INGREDIENTS: Sugar, cocoa butter, cocoa paste, whole milk powder, bulking agent: polydextrose, concentrated butter (milk), glucose syrup, anti-caking agent: isomalt, rapeseed oil, Grand Marnier extract 1.5%, candied orange peel (orange peel, glucose-fructose syrup, sugar, acidifier: citric acid, preservative: sulfur dioxide), mandarine Napoléon 1.2%, invert sugar syrup, dextrin, Cointreau 0.8%, inulin, emulsifier: soy lecithin, natural vanilla flavouring, natural orange flavouring Cocoa solids: dark chocolate min 60%, milk chocolate min 30% white chocolate min 23% ALLERGENS: MAY CONTAIN TRACES OF NUTS, EGGS AND WHEAT (GLUTEN) NUTRITION FACTS/100G: . Energy value (2007kJ/479kcal) . Total fat (27.6g) of which saturates (16.7g). trans fat (0.2g) . Total carbohydrates (48.5g) of which sugars (47.7g) . Total protein (4.2g) . Salt (0.1g) OTHER INFORMATION: - Information producer: Galler Chocolatiers S.A. 39, Rue de la station, 4051 Vaux-sous- Chèvremont, Belgium - Net weight: 350g - Conditions of conservation: keep cool and dry ** DISCLAIMER: The product information as reported by IDF on its website, is provided by IDF suppliers. IDF strives to ensure that the obtained data are complete, correct and up-to-date. IDF cannot be held responsible for the possible inaccuracy or incompleteness of information. By purchasing the product, the consumer explicitly waives all recourse against IDF and IDF Belgium in this respect. In particular, IDF draws the consumer’s attention to the fact that the data on its website do not replace those on the product label. A discrepancy may exist partly because of stock rotation, for example, the presence of new allergenic substances or changes in net weight. -

The 8Th Asia Pacific IAP Congress September 5 (Thu) - 8 (Sun), 2013, Busan, Korea APIAP 2013 the 8Th Asia Pacific IAP Congress

The 8th Asia Pacific IAP Congress September 5 (Thu) - 8 (Sun), 2013, Busan, Korea APIAP 2013 The 8th Asia Pacific IAP Congress September 5 (Thu) - 8 (Sun), 2013, Busan, Korea “Pathology, Opening the Personalized Medicine” Hosted by Korean Division of IAP | Korean Society of Pathologists www.apiap2013.org @apiap2013 3rd Announcement Congress 2013 APIAP 3rd Annoucement CONTENTS 03 Invitation & Welcome Message 04 APIAP 2013 Organizing Committee 05 Program at a Glance 07 Keynote Speakers 08 Spreaker Guidelines 10 Daily Program 19 Registration 21 Accommodation 22 Social Programs 23 Tour Programs 25 Transportation 27 Useful Information 28 About Busan, Korea 30 Sponsors Congress 2013 APIAP Invitation & Welcome Message Dear Colleagues, Dear Colleagues, “Pathology, Opening the Personalized Medicine” In collaboration with Korean Division of IAP and Korean So- ciety of Pathologists, as a secretary general I'm pleased to Increasing importance of pathologic diagnosis has been inform you that the 8th Asia Pacific IAP Congress will take made through several steps. place 5(Thu) to 8(Sun), September, 2013 in Busan, Korea. The most recent step “personalized medicine” changed a lot to pathology and pathologists. Pathology is really a traditional The Korean Society of Pathologists cordially invites you to science but with most recent technology. attend at “The 8th Asia Pacific IAP Congress”. During this 4 days congress; we will bring together scientific and clinical In September 5 – 8, 2013, an important event is held at Bu- leaders from all over the world, as well as young scientists san, Korea. and newcomers to the field of pathology. Therefore the 8th The 8th Congress of Asia-Pacific Division of IAP will be a great Asia Pacific IAP Congress will be a good chance to meet oth- occasion to all pathologists. -

Effect of Α-Tocopherol on the Physicochemical Properties of Sturgeon Surimi During Frozen Storage

Article Effect of α-Tocopherol on the Physicochemical Properties of Sturgeon Surimi during Frozen Storage Shuwei Tang 1, Guangxin Feng 1, Wenxuan Cui 2, Ruichang Gao 3, Fan Bai 4, Jinlin Wang 4, Yuanhui Zhao 1,* and Mingyong Zeng 1,* 1 College of Food Science and Engineering, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266003, China; [email protected] (S.T.); [email protected] (G.F.) 2 Penglai Aquatic Product Technology Promotion Department, Yantai 265600, China; [email protected] 3 School of Food and Bioengineering, Jiangsu University, Jiangsu 212013, China; [email protected] 4 Hangzhou Qiandaohu Sturgeon Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou 310000, China; [email protected] (F.B.); [email protected] (J.W.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (Y.Z.); [email protected] (M.Z.); Tel./Fax: +86-532-8203-2400 (Y.Z.); +86-532-8203-2783 (M.Z.) Received: 17 January 2019; Accepted: 15 February 2019; Published: 15 February 2019 Abstract: This study investigated the effects of α-tocopherol (α-TOH) on the physicochemical properties of sturgeon surimi during 16-week storage at −18 °C. An aliquot of 0.1% (w/w) of α-TOH was added into the surimi and subjected to frozen storage, and 8% of a conventional cryoprotectant (4% sorbitol and 4% sucrose, w/w) was used as a positive control. Based on total viable count, pH and whiteness, α-TOH exhibited a better protection for frozen sturgeon surimi than cryoprotectant during frozen storage. According to soluble protein content, carbonyl content, total sulfhydryl content, and surface hydrophobicity, α-TOH and cryoprotectant showed the same effects on retarding changes of proteins. -

Kirin Holdings Co. Ltd in Beer - World

Kirin Holdings Co. Ltd in Beer - World June 2010 Scope of the Report Kirin Holdings - Beer © Euromonitor International Scope • 2009 figures are based on part-year estimates. • All forecast data are expressed in constant terms; inflationary effects are discounted. Conversely, all historical data are expressed in current terms; inflationary effects are taken into account. • Alcoholic Drinks coverage: Alcoholic Drinks 235 billion litres RTDs/ Wine Beer Spirits High-strength Cider/perry 27 bn litres 184 bn litres 19 bn litres Premixes 1.5 bn litres 4 bn litres Note: Figures may not add up due to rounding Disclaimer Learn More Much of the information in this briefing is of a statistical To find out more about Euromonitor International's complete nature and, while every attempt has been made to ensure range of business intelligence on industries, countries and accuracy and reliability, Euromonitor International cannot be consumers please visit www.euromonitor.com or contact your held responsible for omissions or errors local Euromonitor International office: Figures in tables and analyses are calculated from London + 44 (0)20 7251 8024 Vilnius +370 5 243 1577 unrounded data and may not sum. Analyses found in the Chicago +1 312 922 1115 Dubai +971 4 372 4363 briefings may not totally reflect the companies’ opinions, Singapore +65 6429 0590 Cape Town +27 21 552 0037 reader discretion is advised Shanghai +86 21 63726288 Santiago +56 2 915 7200 2 Kirin Holdings - Beer © Euromonitor International Strategic Evaluation Competitive Positioning Market Assessment Category and Geographic Opportunities Operations Brand Strategy Recommendations 3 Strategic Evaluation Kirin Holdings - Beer © Euromonitor International Kirin Company Facts Kirin Kirin has looked for overseas expansion Headquarters Tokyo, Japan • Kirin has expanded its presence internationally, particularly in Asia Pacific and Australasia. -

OFDC Certified Operators(2017-12) Certificate No.* Certification

OFDC Certified Operators(2017-12) Certification Certification Certificate No.* Certification Consigner Certified Products Expiration date Programs* Location OF-3102-932-1384 Jiangsu Lanshanhu Eco-farm Co., Ltd. Lettuce; Brassica 2018/1/29 01;02 Jiangsu Jiangxi Zhongda Ecological Agriculture Sci. & Tech. OF-3102-936-1259 Paddy 2018/1/4 01;02 Jiangxi Development Co., Ltd. OF-3104-925-1300 Dalian Haiyangdao Fisheries Group Co., Ltd. Sea cucumber; Scallop; Abalone 2018/1/8 01;02 Liaoning OF-3104-965-1440 Xinjiang Bositeng Lake Ecological Fishery Co., Ltd. Shrimp; Fishes; Crab 2018/1/18 01;02 Xinjiang OF-3104-965-1445 Xinjiang Aertai Glacier fish Co., Ltd. Fishes 2018/1/4 01;02 Xinjiang OF-3106-931-1200 Shanghai Tongchu Trading Co., Ltd. Vegetables 2018/1/2 01;02 Shanghai OF-3106-943-1973 Yongzhou Shennong Organic Farm Research Co., Ltd. Vegetables 2018/1/22 01;02 Hu'nan Quanxing Hanhua Agriculture Development Co., Ltd. of OF-3106-944-546 Vegetables; Strawberry 2018/1/14 01;02 Guangdong Guangzhou City OF-3106-964-1264 Ningxia Ninghua Landscape Engineering Co., Ltd. Vegetables; Plum; Peach; Grape 2018/1/12 01;02 Ningxia OF-3108-912-2645A Tianjin Hao Niu Bio-tech Co., Ltd. Alfalfa 2018/1/16 01;02 US Roasted Corn Tea; Roasted Corn Tassel Tea; Roasted Barley Tea; Steamed OP-3002-923-706 Harbin Organic Island Foodstuffs Co., Ltd. 2018/1/3 01;02 Heilongjiang Roasted Barley Tea; Soybean Meal; Corn Flake Zhejiang Qiancenglü Agricultural Development Co., OP-3002-933-1213 Dried osmanthus 2018/1/6 01;02 Zhejiang Ltd. Jiangxi Zhongda Ecological Agriculture Sci. -

MICHELIN Guide Hong Kong Macau 2009: the Selection = = Hong Kong : the Selection =

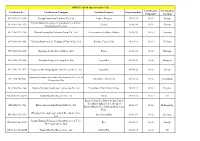

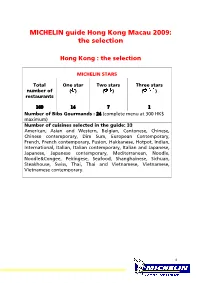

= = MICHELIN guide Hong Kong Macau 2009: the selection = = Hong Kong : the selection = MICHELIN STARS Total One star Two stars Three stars number of ( ) ( ) ( ) restaurants NSV= NQ= T= N= Number of Bibs Gourmands : OQ (complete menu at 300 HK$ maximum) Number of cuisines selected in the guide: 33 American, Asian and Western, Belgian, Cantonese, Chinese, Chinese contemporary, Dim Sum, European Contemporary, French, French contemporary, Fusion, Hakkanese, Hotpot, Indian, International, Italian, Italian contemporary, Italian and Japanese, Japanese, Japanese contemporary, Mediterranean, Noodle, Noodle&Congee, Pekingese, Seafood, Shanghainese, Sichuan, Steakhouse, Swiss, Thai, Thai and Vietnamese, Vietnamese, Vietnamese contemporary. = Q = = Hong Kong: the starred restaurants = o Lung King Heen ô n Amber õ Bo Innovation ó Caprice ö L'Atelier de Joël Robuchon ó Shang Palace ô Summer Palace ô T'ang Court õ m Fook Lam Moon (Wanchai) ô Forum ó Hutong ó Lei Garden (IFC) ó Lei Garden (Tsim Sha Tsui) ó Ming Court ô Petrus ö Pierre õ Regal Palace ô Shanghai Garden ô The Golden Leaf ó The Square ó Tim's Kitchen ò Yung Kee ó = R = = Hong Kong: the Bibs Gourmands = = Café Siam ò Cheung Kee ò Crystal Jade La Mian Xiao Long Bao (TST) ò Farm House ó Golden Bauhinia ó Gunga Din's ò Ho Hung Kee 2 Jashan ó Kin's Kitchen ò Lei Garden (Elements) ó Lei Garden (Mong Kok) ó Le Soleil ó Lian ò Luk Yu Tea House ò Naozen ò 1/5 Nuevo ò Tandoor ó Tasty (Happy Valley) ò Tasty (Hung Hom) 2 Tasty (IFC) 2 West Villa ó Yee Tung Heen ô Yè Shanghai (Admiralty) ó Yunyan ó = -

Tmark Hotel Myeongdong MAP BOOK

Tmark Hotel Myeongdong MAP BOOK 2016.12.01_ver1.0 Tourtips Tmark Hotel Myeongdong Update 2016.12.01 Version 1.0 Contents Publisher Park Sung Jae Chief Editor Nam Eun Jeong PART 01 Map Book Editor Nam Eun Jeong, Yoo Mi Sun, Kim So Yeon Whole Map 5 Myeong-dong 7 Insa-dong 9 Marketing Lee Myeong Un, Park Hyeon Yong, Kim Hye Ran Samcheong-dong&Bukchon 11 Gwanghwamun&Seochon 13 Design in-charge Kim No Soo Design Editor Bang Eun Mi PART 02 Travel Information Map Design Lee Chae Ri Tmark Hotel Myeongdong 15 SM Duty Free 16 Publishing Company Tourtips Inc. 7th floor, S&S Building, 48 Ujeongguk-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul Myeong-dong·Namdaemun·Namsan Mountain 17 Insa-dong·Jongno 24 02 - 6325 - 5201 / [email protected] Samcheong-dong·Bukchon 29 Gwanghwamun·Seochon 33 Website www.tourtips.com Recommended Tour Routes 37 Must-buy items in Korea 38 The 8 Best Items to Buy at SM Duty Free 39 The copyright of this work belongs to Tourtips Inc. This cannot be re-edited, duplicated, or changed without the written consent of the company. For commercial use, please contact the aforementioned contact details. Even for non-commercial use, the company’s consent is needed for large-scale duplication and re-distribution. Map Samcheong-dong&Bukchon 04 Legend 2016.12.01 Update Seoul 01 Whole Map Line 1 1 Line 2 2 Line 3 3 Line 4 4 Line 5 Bukchon Hanok Village 5 Gyeongui•Jungang Line G Airport Railroad Line A Tongin Market Changdeokgung Palace Gyeongbokgung Palace Seochon Anguk Gyeongbokgung 3 안국역 3 경복궁역 Gwanghwamun Insa-dong Jongmyo Shrine Center Mark Hotel 5 Gwanghwamun