Reforming Indonesia's Foreign Ministry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AKAL DAN WAHYU DALAM PEMIKIRAN M. QURAISH SHIHAB Yuhaswita*

AKAL DAN WAHYU DALAM PEMIKIRAN M. QURAISH SHIHAB Yuhaswita* Abstract Reason according to M. Quraish Shihab sense is the thinking power contained in man and is a manipation of the human soul. Reason is not understood materially but reason is understood in the abstract so that sense is interpreted a thinking power contained in the human soul, with this power man is able to gain knowledge and be able to distinguish between good and evil. Revelation according to M. Quraish Shihab, is the delivery of God’s Word to His chosen people to be passed on to human beings to be the guidance of life. God’s revelation contains issues of aqidah, law, morals, and history. Furthermore, M. Quraish Shihab reveals that human reason is very limited in understanding the content of Allah’s revelation, because in Allah’s revelation there are things unseen like doomsday problems, death and so forth. The function of revelation provides information to the sense that God is not only reachable by reason but also heart. Kata Kunci: problematika, nikah siri, rumah tangga Pendahuluan M. Quraish Shihab adalah seorang yang tidak baik untuk dikerjakan oleh ulama dan juga pemikir dalam ilmu al Qur’an manusia. dan tafsir, M. Quraish Shihab termasuk Ketika M. Quraish Shihab seorang pemikir yang aktif melahirkan karya- membahas tentang wahyu, sebagai seorang karya yang bernuansa religious, disamping itu mufasir tentunya tidak sembarangan M. Quraish Shihab juga aktif berkarya di memberikan menafsirkan ayat-ayat al berbagai media massa baik media cetak Qur’an yang dibacanya, Wahyu adalah kalam maupun elektronik, M.Quraish Shihab sering Allah yang berisikan anjuran dan larangan tampil di televise Metro TV memberikan yang harus dipatuhi oleh hamba-hamba-Nya. -

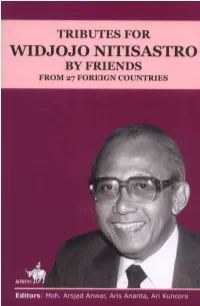

Tributes1.Pdf

Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Law No.19 of 2002 regarding Copyrights Article 2: 1. Copyrights constitute exclusively rights for Author or Copyrights Holder to publish or copy the Creation, which emerge automatically after a creation is published without abridge restrictions according the law which prevails here. Penalties Article 72: 2. Anyone intentionally and without any entitlement referred to Article 2 paragraph (1) or Article 49 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2) is subject to imprisonment of no shorter than 1 month and/or a fine minimal Rp 1.000.000,00 (one million rupiah), or imprisonment of no longer than 7 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (five billion rupiah). 3. Anyone intentionally disseminating, displaying, distributing, or selling to the public a creation or a product resulted by a violation of the copyrights referred to under paragraph (1) is subject to imprisonment of no longer than 5 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 500.000.000,00 (five hundred million rupiah). Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar Aris Ananta Ari Kuncoro Kompas Book Publishing Jakarta, January 2007 Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Published by Kompas Book Pusblishing, Jakarta, January 2007 PT Kompas Media Nusantara Jalan Palmerah Selatan 26-28, Jakarta 10270 e-mail: [email protected] KMN 70007006 Editor: Moh. Arsjad Anwar, Aris Ananta, and Ari Kuncoro Copy editor: Gangsar Sambodo and Bagus Dharmawan Cover design by: Gangsar Sambodo and A.N. -

Female Circumcision: Between Myth and Legitimate Doctrinal Islam

Jurnal Syariah, Jil. 18, Bil. 1 (2010) 229-246 Shariah Journal, Vol. 18, No. 1 (2010) 229-246 FEMALE CIRCUMCISION: BETWEEN MYTH AND LEGITIMATE DOCTRINAL ISLAM Mesraini* ABSTRACT Circumcision on female has sociologically been practiced since long time ago. It is believed to be done for certain purposes. One of the intentions is that it is as an evidence of sacrifice of the circumcised person to get close to God. In the last decades, the demand for ignoring this practice on female by various circles often springs. Reason being is that the practice is accused of inflicting female herself. Moreover, it is regarded as a practice that destroys the rights of female reproduction and that of female sexual enjoyment and satisfaction. Commonly, female circumcision is done by cutting clitoris and throwing the minor and major labia. This practice of circumcision continues based on the myths that spread so commonly among people. This article aims to conduct a research on female circumcision in the perspective of Islamic law. According to Islamic doctrine, female circumcision is legal by Islamic law. By adopting the methodology of syar‘a man qablana (the law before us) and theory of maqasid al-syari‘ah (the purposes of Islamic law) and some other legitimate Quranic verses, circumcision becomes an important practice. Again, the famous female circumcision practice is evidently not parallel with the way recommended by Islam. Keywords: circumcision, female, Islamic law, tradition * Lecturer, State Islamic University Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta, mesraini@yahoo. com 229 Jurnal Syariah, Jil. 18, Bil. 1 (2010) 229-246 INTRODUCTION Circumcision practice is a tradition, known worldwide and admitted by monotheistic religions members especially the Jewish, Muslim and some of the Christians. -

Indonesia Steps up Global Health Diplomacy

Indonesia Steps Up Global Health Diplomacy Bolsters Role in Addressing International Medical Challenges AUTHOR JULY 2013 Murray Hiebert A Report of the CSIS Global Health Policy Center Indonesia Steps Up Global Health Diplomacy Bolsters Role in Addressing International Medical Challenges Murray Hiebert July 2013 About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars are developing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full- time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded at the height of the Cold War by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke, CSIS was dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has become one of the world’s preeminent international institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global health and economic integration. Former U.S. senator Sam Nunn has chaired the CSIS Board of Trustees since 1999. Former deputy secretary of defense John J. Hamre became the Center’s president and chief executive officer in April 2000. CSIS does not take specific policy positions; accordingly, all views expressed herein should be understood to be solely those of the author(s). -

INDONESIA's FOREIGN POLICY and BANTAN NUGROHO Dalhousie

INDONESIA'S FOREIGN POLICY AND ASEAN BANTAN NUGROHO Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia September, 1996 O Copyright by Bantan Nugroho, 1996 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibbgraphic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Lïbraiy of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous papa or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fïim, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substautid extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. DEDICATION To my beloved Parents, my dear fie, Amiza, and my Son, Panji Bharata, who came into this world in the winter of '96. They have been my source of strength ail through the year of my studies. May aii this intellectual experience have meaning for hem in the friture. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents v List of Illustrations vi Abstract vii List of Abbreviations viii Acknowledgments xi Chapter One : Introduction Chapter Two : indonesian Foreign Policy A. -

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: a Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: John O. Haley, Chair Michael E. Townsend Beth E. Rivin Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Law © Copyright 2015 Yu Un Oppusunggu ii University of Washington Abstract Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor John O. Haley School of Law A sweeping proviso that protects basic or fundamental interests of a legal system is known in various names – ordre public, public policy, public order, government’s interest or Vorbehaltklausel. This study focuses on the concept of Indonesian public order in private international law. It argues that Indonesia has extraordinary layers of pluralism with respect to its people, statehood and law. Indonesian history is filled with the pursuit of nationhood while protecting diversity. The legal system has been the unifying instrument for the nation. However the selected cases on public order show that the legal system still lacks in coherence. Indonesian courts have treated public order argument inconsistently. A prima facie observation may find Indonesian public order unintelligible, and the courts have gained notoriety for it. This study proposes a different perspective. It sees public order in light of Indonesia’s legal pluralism and the stages of legal development. -

Pekerja Migran Indonesia Opini

Daftar Isi EDISI NO.11/TH.XII/NOVEMBER 2018 39 SELINGAN 78 Profil Taman Makam Pahlawan Agun Gunandjar 10 BERITA UTAMA Pengantar Redaksi ...................................................... 04 Pekerja Migran Indonesia Opini ................................................................................... 06 Persoalan pekerja migran sesungguhnya adalah persoalan Kolom ................................................................................... 08 serius. Banyaknya persoalan yang dihadapi pekerja migran Indonesia menunjukkan ketidakseriusan dan ketidakmampuan Bicara Buku ...................................................................... 38 negara memberikan perlindungan kepada pekerja migran. Aspirasi Masyarakat ..................................................... 47 Debat Majelis ............................................................... 48 Varia MPR ......................................................................... 71 Wawancara ..................................................... 72 Figur .................................................................................... 74 Ragam ................................................................................ 76 Catatan Tepi .................................................................... 82 18 Nasional Press Gathering Wartawan Parlemen: Kita Perlu Demokrasi Ala Indonesia COVER 54 Sosialisasi Zulkifli Hasan : Berpesan Agar Tetap Menjaga Persatuan Edisi No.11/TH.XII/November 2018 Kreatif: Jonni Yasrul - Foto: Istimewa EDISI NO.11/TH.XII/NOVEMBER 2018 3 -

Governing the International Commercial Contract Law: the Framework of Implementation to Establish the ASEAN Economy Community 2015

Governing the International Commercial Contract Law: The Framework of Implementation to Establish the ASEAN Economy Community 2015 Taufiqurrahman, University of Wijaya Putra, Indonesia Budi Endarto, University of Wijaya Putra, Indonesia The Asian Conference on Business and Public Policy 2015 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract The Head of the State Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in Summit of Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2007 on Cebu, Manila agreed to accelerate the implementation of ASEAN Economy Community (AEC), which was originally 2020 to 2015. This means that within the next seven months, the people of Indonesia and ASEAN member countries more integrated into one large house named AEC. This in turn will further encourage increased volume of international trade, both by the domestic consumers to foreign businesses, among foreign consumers by domestic businesses, as well as between foreign entrepreneurs with domestic businesses. As a result, the potential for legal disputes between the parties in international trade transactions can not be avoided. Therefore, the existence of the contract law of international commercial law in order to provide maximum protection for the parties to a transaction are indispensable. The existence of this legal regime will provide great benefit to all parties to a transaction to minimize disputes. This study aims to assess the significance of the governing of International Commercial Contract Law for Indonesia in the framework of the implementation of establishing the AEC 2015 and also to find legal principles underlying governing the International Commercial Contracts Law for Indonesia in the framework of the implementation of establishing the AEC 2015 so as to provide a valuable contribution to the development of Indonesian national law. -

Nabbs-Keller 2014 02Thesis.Pdf

The Impact of Democratisation on Indonesia's Foreign Policy Author Nabbs-Keller, Greta Published 2014 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Griffith Business School DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2823 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366662 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au GRIFFITH BUSINESS SCHOOL Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By GRETA NABBS-KELLER October 2013 The Impact of Democratisation on Indonesia's Foreign Policy Greta Nabbs-Keller B.A., Dip.Ed., M.A. School of Government and International Relations Griffith Business School Griffith University This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. October 2013 Abstract How democratisation affects a state's foreign policy is a relatively neglected problem in International Relations. In Indonesia's case, there is a limited, but growing, body of literature examining the country's foreign policy in the post- authoritarian context. Yet this scholarship has tended to focus on the role of Indonesia's legislature and civil society organisations as newly-empowered foreign policy actors. Scholars of Southeast Asian politics, meanwhile, have concentrated on the effects of Indonesia's democratisation on regional integration and, in particular, on ASEAN cohesion and its traditional sovereignty-based norms. For the most part, the literature has completely ignored the effects of democratisation on Indonesia's foreign ministry – the principal institutional actor responsible for foreign policy formulation and conduct of Indonesia's diplomacy. Moreover, the effect of Indonesia's democratic transition on key bilateral relationships has received sparse treatment in the literature. -

Living Adat Law, Indigenous Peoples and the State Law: a Complex Map of Legal Pluralism in Indonesia Mirza Satria Buana

Living adat Law, Indigenous Peoples and the State Law: A Complex Map of Legal Pluralism in Indonesia Mirza Satria Buana Biodata: A lecturer at Lambung Mangkurat University, South Kalimantan, Indonesia and is currently pursuing a Ph.D in Law at T.C Beirne, School of Law, The University of Queensland, Australia. The author’s profile can be viewed at: http://www.law.uq.edu.au/rhd-student- profiles. Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper examines legal pluralism’s discourse in Indonesia which experiences challenges from within. The strong influence of civil law tradition may hinder the reconciliation processes between the Indonesian living law, namely adat law, and the State legal system which is characterised by the strong legal positivist (formalist). The State law fiercely embraces the spirit of unification, discretion-limiting in legal reasoning and strictly moral-rule dichotomies. The first part of this paper aims to reveal the appropriate terminologies in legal pluralism discourse in the context of Indonesian legal system. The second part of this paper will trace the historical and dialectical development of Indonesian legal pluralism, by discussing the position taken by several scholars from diverse legal paradigms. This paper will demonstrate that philosophical reform by shifting from legalism and developmentalism to legal pluralism is pivotal to widen the space for justice for the people, particularly those considered to be indigenous peoples. This paper, however, only contains theoretical discourse which was part of pre-liminary -

Bab I Pendahuluan

1 BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Latar Belakang Masalah Indonesia sebagai Negara kepulauan terbesar di dunia karena jumlah kepulauanya sekitar tiga belas ribu kepulauan dan jumlah penduduk hampir mencapai dua ratus juta jiwa. Bahkan Indonesia dikenal juga sebagai masyarakat yang terligius dan beradab karena masyarakatnya bertuhan. Dalam kaitan ini, Joahim Wach menegaskan bahwa tidak ada agama tanpa Tuhan karena agama adalah perbuatan manusia yang paling mulia dalam kaitannya dengan Tuhan Yang Maha Pencipta. Kepadanya manusia memberikan kepercayaan dan keterkaitan yang sesungguhnya.1 Hal ini, sesuai dengan keyakinan agama yang dianut oleh masyarakat Indonesia, bahkan diperkuat dengan falsafah bangsa Indonesia yang termuat dalam Pancasila yang pertama adalah Ketuhanan Yang Maha Esa. Agama yang ada di Indonesia adalah bertuhan karena tidak bertuhan berarti bertentangan dengan Pancasila, bahkan tidak diakui sebagai agama. Maka keberadaan Tuhan adalah masalah pokok dalam setiap agama karena agama tanpa kepercayaan kepada Tuhan tidak disebut agama.2 Oleh karena itu, Edward B. Tylor mendefinisikan agama sebagai “belief in spiritual being” karena agama termasuk suatu 1 Joachim Wach, The Comparative Study of Religion, {New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1958}, hlm. XXXIV 2 Zaenul Arifin, Menuju Dialog Islam Kristen Berjumpaan Gereja Ortodoks Syria dengan Islam, {Semarang: Walisongo Press, 2010}, cet. 1, hlm. 3 2 kepercayaan kepada suatu yang wujud yang tidak bisa dialami oleh proses pengalaman yang biasa.3 Begitu pula, Emile Durkheim menyatakan bahwa agama adalah suatu system kepercayaan yang disatukan oleh praktek-praktek yang bertalian dengan hal-hal yang suci, yakni hal-hal yang dibolehkan dan dilarang, kepercayan dan praktek- praktek yang mempersatukan suatu komunitas moral yang terpaut satu sama lain.4 Agama yang dipercayai oleh masyarakat Indonesia adalah Islam, Kristen, Hindu, Buddha, dan Konghuchu. -

Indonesia Matters: the Role and Ambitions of a Rising Power

INDONESIA MATTERS: THE ROLE AND AMBITIONS OF A RISING POWER Summer 2013 With the support of In association with Media partners 2 Friends of Europe | Global Europe INDONESIA MATTERS: THE ROLE AND AMBITIONS OF A RISING POWER Report of the high-level European Policy Summit co-organised by Friends of Europe and The Mission of Indonesia to the EU with the support of British Petroleum (BP), British Council and Delhaize Group in association with Bank Indonesia and Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and with media partners Jakarta Post and Europe's World Summer 2013 Brussels This report reflects the conference rapporteur’s understanding of the views expressed by participants. Moreover, these views are not necessarily those of the organisations that participants represent, nor of Friends of Europe, its Board of Trustees, members or partners. Reproduction in whole or in part is permitted, provided that full credit is given to Friends of Europe and that any such reproduction, whether in whole or in part, is not sold unless incorporated in other works. Rapporteur: Phil Davis Publisher: Geert Cami Project Director: Nathalie Furrer Project Manager: Patricia Diaz Project Assistant: Daniele Brunetto Photographer: François de Ribacourt Design & Layout: Heini Järvinen Cover image: Adit Chandra This report is printed on sustainably produced paper Table of contents Executive summary 5 The recasting of a nation 7 Rapid emergence of a new world power 11 On track to become 7th largest economy? 14 The challenge to future growth 16 Social structures struggle to keep up with pace of change 21 EU slow to grasp Indonesian opportunity 24 The process of reform must go on 26 Annex I – Programme 28 Annex II – List of Participants 31 4 Friends of Europe | Asia Programme Indonesia Matters: the role and ambitions of a rising power | Summer 2013 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Indonesia’s success in consolidating democracy and achieving rapid economic growth has propelled the country into a position of regional and global power.