The Viability of Community Tourism in Least Developed Countries: the Case of Zanzibar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flight Calibration of Landing and Navigation Aids

UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA AIC TANZANIA CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY Aeronautical Information Management 05/19 Nyerere/ Kitunda Road Junction FAX: (255 22) 2844300, 2844302 (Pink 70) Aviation House, 1st Floor, PHONE: (255 22) 2198100, 2844291. P.O. Box 2819, DAR ES SALAAM AFS: HTDQYOYO 07 OCT Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.tcaa.go.tz Document No: Title: AIC Page 1 of 2 TCAA/FRM/ANS/AIS-30 The following circular is promulgated for information, guidance and necessary action Hamza S. Johari Director General FLIGHT CALIBRATION OF LANDING AND NAVIGATIONAL AIDS The following Landing and Navigational Aids in the Dar es Salaam Flight Information Region (DAR FIR) were flight checked and approved for operational use on the dates indicated:- 1. Julius Nyerere International Airport – HTDA i) ILS (GP) and (LLZ) Runway 05 routine flight checked on 11 September 2019 and approved for operational use. ii) PAPI Runway 05 and 23 routine flight checked on 11 March 2019 and approved for operational use. iii) ‘DV’ DVOR/DME DV 112.7 MHz routine flight check carried out on 25 September 2018 and approved for operational use. 2. Kilimanjaro International Airport – HTKJ i) ‘KV’ DVOR/DME KV 115.3 MHz routine flight checked on 24 September 2018 and approved for operational use. ii) ILS (GP) and (LLZ) Runway 09 routine flight checked on 09 September 2019 and approved for operational use. iii) PAPI Runway 09 and 27 routine flight checked on 05 March 2019 and approved for operational use. 3. Abeid Amani Karume International Airport – HTZA i) PAPI Runway 18 and 36 routine flight checked on 10 March 2019 and approved for operational use. -

SYNOPTIC SUMMARY Pemba Airport, with About 360 Mm Reported During the Third Dekad

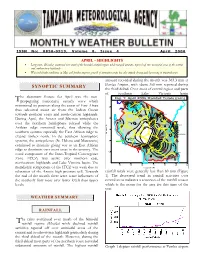

ISSN No: 0856-0919, Volume 8, Issue 4 April 2006 APRIL – HIGHLIGHTS • Long rains (Masika) continued over much of the bimodal rainfall regime while rainfall activities tapered off over unimodal areas of the central and southwestern highlands • Wet and cloudy conditions in May will further improve growth of immature crops but also impede drying and harvesting of matured crops amount recorded during the month was 563.3 mm at SYNOPTIC SUMMARY Pemba Airport, with about 360 mm reported during the third dekad. Over most of central region and parts of southern Lake Victoria basin he dominant feature for April was the non- Fig. 1: April 2006 Rainfall Totals (mm) T propagating (stationary) easterly wave which Bukoba Kayanga Musoma maintained its position along the coast of East Africa 2 thus advected moist air from the Indian Ocean Ngara Mwanza Arusha Shinyanga Moshi towards northern coast and north-eastern highlands. Mbulu Same 4 Babati During April, the Azores and Siberian anticyclones Kasulu Singida Kigoma Urambo Tanga over the northern hemisphere relaxed while the Tabora Handeni Pemba Pangani Arabian ridge remained weak, thus allowing the 6 Dodoma ude (°S) t i Zanzibar southern systems especially the East African ridge to t Morogoro La Dar es Salaam extend further north. In the southern hemisphere Iringa Sumbawanga systems, the anticyclones (St. Helena and Mascarene) 8 continued to intensify giving way to an East African Mbozi Mbeya Mufindi Mahenge Kilwa ridge to dominate over most areas in the country. The Makete 10 Mtwara zonal component of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Songea Zone (ITCZ) was active over northern cost, Newala northeastern highlands and Lake Victoria basin. -

A TRIANGLE of VULNERABILITY Changing Patterns of Illicit Trafficking Off the Swahili Coast

RESEARCH REPORT A TRIANGLE OF VULNERABILITY Changing patterns of illicit trafficking off the Swahili coast ALASTAIR NELSON JUNE 2020 A TRIANGLE OF VULNERABILITY Changing patterns of illicit trafficking off the Swahili coast W Alastair Nelson JUNE 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study is based on knowledge, understanding and personal experiences from numerous people who shared their time and insights with us during the research and writing. Some of these were dispassionate, some deeply personal and based on incredible lived histories. Profound thanks are due to everyone who gave their time, insights and reflections. Thanks are due to ‘field researcher #1’ who undertook independent field- work, accompanied the author in the field, and used prior connections to some of the illicit networks to develop our understanding of the illicit flows in this triangle. Thanks to Simone Haysom for support in the field and numerous discussions to guide the work all the way through, also to Julian Rademeyer for input and critical motivation towards the end. Mark Shaw and Julia Stanyard gave crucial intellectual input and transformed the structure of the report. Thanks to Tuesday Reitano and Monique de Graaff for making things happen. Also, to Mark Ronan, Pete Bosman and Jacqui Cochrane of the GI editorial and production team for producing the maps and the final report. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Alastair coordinates the GI’s Resilience Fund work in Mozambique and conducts research into illicit trafficking, with a particular focus on the illegal wildlife trade. He has 25 years’ experience implementing and leading field-conservation programmes in the Horn of Africa, East and southern Africa. -

World Bank Document

Zanzibar: A Pathway to Tourism for All Public Disclosure Authorized Integrated Strategic Action Plan July 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1 List of Abbreviations CoL Commission of Labour DMA Department of Museums and Antiquities (Zanzibar) DNA Department of National Archives (Zanzibar) GDP gross domestic product GoZ government of Zanzibar IFC International Finance Corporation ILO International Labour Organization M&E monitoring and evaluation MoANRLF Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources, Livestock and Fisheries (Zanzibar) MoCICT Ministry of Construction, Industries, Communication and Transport (Zanzibar) MoEVT Ministry of Education and Vocational Training (Zanzibar) MoFP Ministry of Finance and Planning (Zanzibar) MoH Ministry of Health (Zanzibar) MoICTS Ministry of Information, Culture, Tourism and Sports (Zanzibar) MoLWEE Ministry of Lands, Water, Energy and Environment (Zanzibar) MoTIM Ministry of Trade, Industry and Marketing (Zanzibar) MRALGSD Ministry of State, Regional Administration, Local Government and Special Departments (Zanzibar) NACTE National Council for Technical Education (Tanzania) NGO nongovernmental organization PPP private-public partnership STCDA Stone Town Conservation and Development Authority SWM solid waste management TISAP tourism integrated strategic action plan TVET technical and vocational education and training UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation UWAMWIMA Zanzibar Vegetable Producers’ Association VTA Vocational -

Kwanini Carrying Capacity Assessment Study

Kwanini Carrying Capacity Assessment June - September 2014 Investors Government Guests Kwanini People Workforce Prepared for Ministry of Information, Culture, Tourism and Sports Hon. Said Ali Mbarouk By Denise Bretlaender & Pavol Toth Table of Contents KWANINI CARRYING CAPACITY ASSESSMENT ................................................................................................................. 1 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 3 2. LITERATURE REVIEW ....................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 SUSTAINABLE TOURISM ....................................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 MANAGEMENT TOOLS FOR SUSTAINABLE TOURISM .................................................................................................. 4 3. CARRYING CAPACITY EXERCISE ........................................................................................................................ 5 4. METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................................................................. 8 5. ANALYSES ...................................................................................................................................................... 10 5. 1 CURRENT STATE OF TOURISM ............................................................................................................................ -

MOZAMBIQUE November 2019 - October 2020

MOZAMBIQUE November 2019 - October 2020 1 There would be no us without you. 2 4 Sense of Oceans - Who we are 6 About Us 8 Our people 10 Product offering 12 Sustainable tourism 14 Systems through technology 16 Regional maps 18 Parks of Mozambique 20 Attractions of Mozambique MOZAMBIQUE 22 Introduction 24 Country information 26 Tours at a Glance COMFORT TOUR 28 Mozambique Highlights CLASSIC TOUR 30 Northern Mozambique Explorer COMFORT SELF-DRIVE TOUR 32 Bush and Beach Comfort 34 Accommodation KENYA 44 Introduction 46 Country information CLASSIC GUIDED TOUR 48 Tsavo East and Tsavo West: Safari and Beach TANZANIA 50 Introduction 52 Country information CLASSIC GUIDED TOUR 54 Tanzania and Zanzibar: Safari and Beach 56 ADD ON PACKAGES 58 COMING SOON Reunion and Madagascar 60 INDEX Contents 3 Sense of Oceans… Who we are For over three decades, Tourvest Destination Management has prided itself in offering only the highest quality, most memorable and professional tour services to both local and international travellers. With our aim to grow our already expansive African footprint, we have joined hands with Mozambique Voyages to form Sense of Oceans – a division that will take both organisations into a new phase of exploring travel possibilities throughout the Indian Ocean, starting with Mozambique. Sense of Oceans combines the expertise of two successful organisations. Mozambique Voyages specialises in both self-drive and tailor-made holidays in Mozambique and are known for providing travellers with an unprecedented level of access and specialisation to ensure truly unforgettable travel experiences. On the other hand, Tourvest Destination Management’s heritage and reputation as one of the best destination management companies in Africa is proven by our inbound business unit being the largest ground handler of foreign tourists to Africa. -

Tanzania Civil Aviation Authority Public Notice

TANZANIA CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY PUBLIC NOTICE THE TANZANIA CIVIL AVIATION (LICENSING OF AIR SERVICES) REGULATIONS, 2006 AND (GROUND HANDLING SERVICES) REGULATIONS, 2007 BOARD DECISIONS ON APPLICATIONS FOR AIR AND GROUND HANDLING SERVICES LICENCES At its 9th Ordinary Licensing Meeting held on 21 October 2009 at Mövenpick Royal Palm Hotel, the Tanzania Civil Aviation Authority Board considered among other things, applications for air and ground handling services licences from companies/operators listed hereunder and reached the following decisions: A. APPLICANTS FOR AIR SERVICES LICENCES NO. APPLICANT APPLICATION BOARD DECISION STATUS SERVICES APPLIED FOR 1. M/S Blue Sky Aviation Licence renewal Air charter services Approved for a period of Limited, six (6) months, with P.O. Box 18518, conditions. Nairobi, Kenya. 2. M/S Spears Air Limited, Licence renewal Air charter services Approved for a period of P.O. Box 2782, two (2) years, with Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. conditions. 3. M/S Tanzanair Limited, Licence renewal (i) Scheduled services on the following Approved for a period of P.O. Box 364, routes: two (2) years, with Dar es Salaam, Tanzania conditions. Dar-Zanzibar-Dar; Dar-Zanzibar-Arusha-Zanzibar-Dar; Dar-Mwanza-Bukoba-Mwanza-Dar; Dar-Mafia-Dar; Dar-Kilwa-Dar; Dar-Lindi-Dar; Dar-Iringa-Mbeya-Iringa-Dar; Dar-Songea-Dar. (ii) Air charter services; (iii) Aerial work services. 4. M/S Desert Locust Control Licence renewal Air charter services Approved for a period of of Eastern Africa (DLCO- two (2) years, with EA), conditions. P.O. Box 2273, Mwanza, Tanzania. 5. M/S Airspray (T) Limited, Licence renewal Aerial work services (crop spraying) Approved for a period of P.O. -

The Tanzanian Tide Gauge Network

THE TANZANIAN SEA LEVEL NETWORK: A NATIONAL REPORT (DRAFT) Shigalla B. Mahongo Tanzania Fisheries Research Institute P.O. Box 9750, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania [Tel: +255 51 650045; Fax: +255 51 650043; Email: [email protected]] BACKGROUND This report has been prepared for the Western Indian Ocean Project within the framework of the IOC-Sida-Flinders Marine Science Programme and in response to recommendations that were put forward by IOCINCWIO-IV. 1. INTRODUCTION The Tanzanian sea level network consists of two operational stations of Zanzibar and Dar es Salaam. There are also three non-operational tide gauges at Mtwara, Tanga and Pemba. The Zanzibar Station has a Handar encoder with satellite communication. In the 1990 GLOSS plan, Zanzibar and Mtwara were proposed as GLOSS stations among 17 stations in the IOCINCWIO. An IOCINCWIO workshop held in Mombassa in 1991 further recommended the establishment of Dar es Salaam and Tanga stations, out of 15 extra GLOSS stations proposed in the region. The new tide gauge in Zanzibar was installed in 1990, replacing the old Munro IH 109 float gauge (1983-1993). The Dar es Salaam station has a mechanical SEBA float gauge, which was installed in 1997. This tide gauge replaced a Leupold and Stevens float gauge (1986-1990) whose stilling well was damaged by a boat. The tide gauge in Mtwara was a Munro IH 109 float type, which worked from 1959 to 1962. Previously, a Munro IH 40 was in operation from 1956 to 1957. A Munro IH 40 tide gauge in Tanga worked from 1962 to 1966, while that of Pemba (Munro IH 109) was incorrectly installed in 1991 and so it never worked. -

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze Zestawienie Zawiera 8372 Kody Lotnisk

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze zestawienie zawiera 8372 kody lotnisk. Zestawienie uszeregowano: Kod ICAO = Nazwa portu lotniczego = Lokalizacja portu lotniczego AGAF=Afutara Airport=Afutara AGAR=Ulawa Airport=Arona, Ulawa Island AGAT=Uru Harbour=Atoifi, Malaita AGBA=Barakoma Airport=Barakoma AGBT=Batuna Airport=Batuna AGEV=Geva Airport=Geva AGGA=Auki Airport=Auki AGGB=Bellona/Anua Airport=Bellona/Anua AGGC=Choiseul Bay Airport=Choiseul Bay, Taro Island AGGD=Mbambanakira Airport=Mbambanakira AGGE=Balalae Airport=Shortland Island AGGF=Fera/Maringe Airport=Fera Island, Santa Isabel Island AGGG=Honiara FIR=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGH=Honiara International Airport=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGI=Babanakira Airport=Babanakira AGGJ=Avu Avu Airport=Avu Avu AGGK=Kirakira Airport=Kirakira AGGL=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova Airport=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova, Santa Cruz Island AGGM=Munda Airport=Munda, New Georgia Island AGGN=Nusatupe Airport=Gizo Island AGGO=Mono Airport=Mono Island AGGP=Marau Sound Airport=Marau Sound AGGQ=Ontong Java Airport=Ontong Java AGGR=Rennell/Tingoa Airport=Rennell/Tingoa, Rennell Island AGGS=Seghe Airport=Seghe AGGT=Santa Anna Airport=Santa Anna AGGU=Marau Airport=Marau AGGV=Suavanao Airport=Suavanao AGGY=Yandina Airport=Yandina AGIN=Isuna Heliport=Isuna AGKG=Kaghau Airport=Kaghau AGKU=Kukudu Airport=Kukudu AGOK=Gatokae Aerodrome=Gatokae AGRC=Ringi Cove Airport=Ringi Cove AGRM=Ramata Airport=Ramata ANYN=Nauru International Airport=Yaren (ICAO code formerly ANAU) AYBK=Buka Airport=Buka AYCH=Chimbu Airport=Kundiawa AYDU=Daru Airport=Daru -

PRECISION AIR to LAUNCH FLIGHTS to PEMBA Dar Es

PRECISION AIR TO LAUNCH FLIGHTS TO PEMBA Dar es Salaam…. Tanzania’s leading airline, Precision Air will start flights to Pemba Island in Zanzibar. The announcement was made through a press release issued yesterday by the Corporate Communications Office. Flights to the exotic island are expected to commence on 24th May 2016 with three flights a week. Using their state of the art aircraft; ATR72-500. Precision Air will be flying to Pemba via Zanzibar every Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, Departing from Dar es salaam at 07:30am and arriving in Pemba at 09:05am. Returning leg will see flights departing from Pemba at 09:30am and arriving in Dar es salaam at 11:00am The announcement came shortly after Zanzibar Airport Authority (ZAA) upgraded Pemba airport to category four, which meets international required standards for any commercial flight operations. Commenting on the launch, Precision Air’s Commercial Director Mr. Robert Owusu said that, Precision Air is set to offer reliable and comfortable flights to Pemba. He hailed ZAA efforts to upgrade Pemba airport as this will ensure the safety of passengers and aircraft using it. He also stated that Precision Air is the only IOSA certified airline in Tanzania, and always puts safety standards above everything else. “We are very excited about this new route, this will be our 11th domestic route in our mission to connect Tanzania with our network. We are happy to give our customers access to the exotic beaches in Pemba. This will also play a hand in businesses booming in Pemba through the movements between Zanzibar and the mainland.” He added. -

January 2021

PRODUCT | OFFERS | NEWS QUARTERLY DESTINATION UPDATE - JANUARY 2021 1 > CONTENTS SOUTHERN AFRICA • COVID-19 Facts Page 3 • Exclusive Journeys Page 4 • South Africa Update Page 5 • Botswana Update Page 6 KENYA • COVID-19 Facts Page 7 • Special Offers Page 8 • Product Update Page 9 • News Page 10 TANZANIA • COVID-19 Facts Page 11 • Special Offers & News Page 12 • Product Update Page 13 RWANDA & UGANDA • Rwanda COVID-19 Facts Page 14 • Uganda COVID-19 Facts Page 15 • Rwanda & Uganda Updates Page 16 CONTACT US Page 17 2 < > SOUTHERN AFRICA | COVID-19 FACTS As the world’s premier network of luxury destination A&K is there every step of the way management companies, A&K Destination We pride ourselves in being on the ground with our guests Management is unsurpassed at delivering customized, every step of the way - and that was even before the pandemic. We provide 24/7 support, seven days a week. expertly managed travel experiences - and uniquely A&K’s worldwide network is always on hand to answer qualified to protect your wellbeing when travelling in questions and address any concerns you may have. Our the wake of COVID-19. offices are experienced in handling emergencies and have the contacts and knowledge to support guests around the clock in Guest safety comes first the event of medical challenges, including, if necessary, In recognition of our dedication and commitment to Safe arranging doctor’s visits or even emergency Travel Protocols, A&K has received the global World Travel & medical evacuation. Tourism Council’s (WTTC) Safe Travels Stamp. We follow the guidelines established by the leading health experts As destination experts we are here to assist our Travel (including World Health Organization) to minimize any Partners every step of the way. -

Zanzibar Statistical Abstract 2017

ZANZIBAR STATISTICAL ABSTRACT 2017 Annual Inflation Rate 25.0 20.5 20.0 14.7 15.0 9.2 9.4 10.0 Percent 6.1 6.7 5.0 5.6 5.7 5.6 5.0 0.0 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Year Office of the Chief Government Statistician Zanzibar May, 2018 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF GOVERNMENT STATISTICIAN ZANZIBAR STATISTICAL ABSTRACT 2017 Office of the Chief Government Statistician P. O. Box 2321 Telephone: +255 24 331869 Fax: +255 24 331742 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ocgs.go.tz Zanzibar i P R E F A C E The Statistical Abstract has been such an important source of information which presents data for the users. Data from all sectors of the economy and social aspects are compiled and presented by OCGS. This will hopefully enhance the use of statistics for planning and decision-making. The Abstract presents brief information on the legislature, population, agriculture, industries, electricity and water, hotel and commerce, employment, Consumer Price Index and the general economy for the years 2008-2017. We are most grateful and thankful to all who participated in making this publication available. We look forward to continue cooperating with them all. Office of the Chief Government Statistician welcomes comments from users not only on the quality of data published but also on the relevance and additional statistical series they would like to be included in order to strengthen the Zanzibar Statistical System. Any comment should be channeled to: E-mail [email protected].