The Pharmacogenomics Journal https://doi.org/10.1038/s41397-018-0016-6

ARTICLE

Associations between genetic polymorphisms of membrane transporter genes and prognosis after chemotherapy: meta-analysis and finding from Seoul Breast Cancer Study (SEBCS)

Ji-Eun Kim1 Jaesung Choi1 JooYong Park1 Chulbum Park1 Se Mi Lee2 Seong Eun Park3 Nan Song4

- ●

- ●

- ●

- ●

- ●

- ●

- ●

Seokang Chung5 Hyuna Sung6 Wonshik Han4,7 Jong Won Lee8 Sue K. Park1,4,9 Mi Kyung Kim10

- ●

- ●

- ●

- ●

- ●

- ●

Dong-Young Noh4,7 Keun-Young Yoo9,11 Daehee Kang1,4,9,12 Ji-Yeob Choi1,4,9

- ●

- ●

- ●

Received: 7 June 2017 / Revised: 13 October 2017 / Accepted: 4 December 2017 © Macmillan Publishers Limited, part of Springer Nature 2018

Abstract

Membrane transporters can be major determinants of the pharmacokinetic profiles of anticancer drugs. The associations between genetic variations of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) and solute carrier (SLC) genes and cancer survival were investigated through a meta-analysis and an association study in the Seoul Breast Cancer Study (SEBCS). Including the SEBCS, the meta-analysis was conducted among 38 studies of genetic variations of transporters on various cancer survivors. The population of SEBCS consisted of 1 338 breast cancer patients who had been treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. A total of 7 750 SNPs were selected from 453 ABC and/or SLC genes typed by an Affymetrix 6.0 chip. ABCB1 rs1045642 was associated with poor progression-free survival in a meta-analysis (HR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.07–1.64). ABCB1, SLC8A1, and SLC12A8 were associated with breast cancer survival in SEBCS (Pgene < 0.05). ABCB1 rs1202172 was differentially associated with survival depending on the chemotherapy (Pinteraction = 0.035). Our finding provides suggestive associations of membrane transporters on cancer survival.

Introduction

chemotherapy has been demonstrated in breast cancer survival, the heterogeneity of response among patients still exists [3–5]. Such inter-individual differences can be elucidated by genetic variations of pharmacogenes that are involved in drug absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) [6].

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer in Korean women, and an increasing trend has been seen in the mortality of breast cancer [1, 2]. Although the effect of adjuvant

Application of genome-wide association studies

(GWAS) in pharmacogenomics has been increased since 2007. Pharmacogenomic information could be used for

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article

(https://doi.org/10.1038/s41397-018-0016-6) contains supplementary

material, which is available to authorized users.

- * Ji-Yeob Choi

- Institute, Bethesda MD USA

7

Department of Surgery, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

1

Department of Biomedical Sciences, Seoul National University Graduate School, Seoul, Korea

8

Department of Surgery, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

2

College of Pharmacy Chonnam National University, Gwangju, Korea

9

Department of Preventive Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

3

College of Pharmacy, Duksung Women’s university, Seoul, Korea

10

Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Management, National Cancer Center, Goyang, Korea

4

Cancer Research Institute, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

11

The Armed Forces Capital Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

5

Division for New Health Technology Assessment, National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency, Seoul, Korea

12

Institute of Environmental Medicine, Seoul National University Medical Research Center, Seoul, Korea

6

Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer

J-E Kim et al.

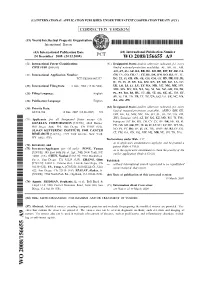

346 records identified through PubMed searching

(Jan, 2000 – Dec, 2016)

472 records identified through EMBASE searching

(Jan, 2000 – Dec, 2016)

making practical decisions on drug prescriptions for an individual patient [7, 8]. However, GWAS in pharmacogenomics has potential limitations on sample size, replication of findings and understanding of drug response mechanisms [7, 9]. Previously, a two-stage GWAS on disease-free survival (DFS) in breast cancer stratified by tumor subtypes in the Seoul Breast Cancer Study (SEBCS) was conducted. Although two loci close to the methenyltetrahyfrofolate synthetase (MTHFS) and H3 histone protein (H3K27Ac) detected from GWAS were associated with DFS in response to treatment, it is difficult to understand the mechanisms of inter-individual differences in drug response from the GWAS in SEBCS [10].

572 records remained after duplicates removed

274 records removed

Not original article or meta-analysis (n=107) Unrelated topic (n=160) Not accessible (n=7)

298 records screened on the base of abstract and title

206 records excluded

No chemotherapy or antitumor agent (n=47) Not for human study (n=35) No transporter genes (n=54) Abstract without full-text (n=70)

Full-text articles assessed for eligibility (n=92)

In this study, we mainly focused on drug transporters involved in drug absorption and elimination. There are two major subfamilies of transporters: ATP-binding cassette (ABC) and solute carrier (SLC). The ABC transporters are efflux pumps that are involved in the movement of intracellular substrates using ATP hydrolysis energy, often against the concentration gradient. The SLC transporters are involved in the uptake of substrates depending on concentration gradient [11–13]. Impaired delivery of drug can result in poor absorption and, increased elimination of drug and can affect drug sensitivity due to genetic alterations of transporter genes [14].

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between genetic polymorphisms of ABC and SLC transporters and breast cancer survival among patients who had been treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. First, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to summarize previously conducted genetic association studies. Second, we investigated the association between genetic variations of transporter genes and breast cancer survival among patients who had received adjuvant chemotherapy based on GWAS in SEBCS.

55 full-text articles excluded

No qualified data (n=55)

37 studies met the inclusion criteria

The current study (SEBCS) included

38 studies included in the meta-analysis

Fig. 1 Flow chart summarizing the literature search and selection process for inclusion of studies

(d) no chemotherapy or antitumor agent (n = 47); (e) not for human study (n = 35); (f) no transporter gene (n = 54); (g) abstract without full text (n = 70); (h) no qualified data (n = 55). A total of 38 studies including SEBCS were considered eligible for the meta-analysis. All the reviewed articles in the present study were limited to English language reports (Fig. 1).

Data extraction and outcomes for meta-analysis

The following data were extracted: author, year, ethnicity, gene, variant, type of cancer, regimen of chemotherapy, type of outcome and estimates (hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI)) by three reviewers (JEK, CBP, and JYC). If one study was conducted separately by the type of regimen or ethnicity, the study was separated as (a) and (b) [15–19].

Methods

Search strategies and selection criteria for metaanalysis

The outcomes were classified as overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), disease-free survival (DFS), and time-to-progression (TTP). OS is defined as the time from randomization to death from any cause. PFS is defined as time from randomization until disease progression or death from any cause. DFS is defined as the time from randomization until recurrence of tumor or death from any cause [20]. TTP is defined as the time from treatment start to disease progression [21].

A systematic literature search was performed in PubMed and EMBASE from January 2000 to December 2016 using the following terms: “transporter” (“ABC” OR “SLC”) AND “cancer [title]” AND (“pharmacogenetics” OR “pharmacogenomics” OR “SNP”) AND (“therapy” OR “treatment” OR “drug” OR “medicine”) AND (“survival” OR “response” OR “outcome” OR “prognosis”).

After removing duplicates in the electronic databases, the following study exclusion criteria was applied for 572 studies: (a) not original article or meta-analysis (n = 107); (b) unrelated topic (n = 160); (c) not accessible articles (n = 7);

The results were extracted according to the following genetic models: additive, dominant, and codominant (homozygote and heterozygote). In the additive model, the

Associations between genetic polymorphisms of membrane transporter genes and prognosis after. . .

risk of disease depends on increasing the number of the minor alleles. In the dominant model, genotypes including any minor allele contribute equally to the phenotype. In the codominant model, the heterozygote is between a major allele homozygote and minor allele homozygote. in the previous study [23]. SNPs were mapped to genes considering 10 kb upstream and downstream of the coding region. We excluded the SNPs with minor allele frequency (MAF)<1% and a P-value <10−4 for deviation from Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE).

- Study population of SEBCS

- Statistical analysis

As a multicenter case-control study, the SEBCS included 4 040 incident breast cancer patients who were recruited from Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH), ASAN Medical Center (AMC) and the National Cancer Center (NCC) from 2001 to 2007. Detailed information has been presented in the previous studies [10, 22]. All patients provided written informed consent for the study. The study design was approved by the Committee on Human Research of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. H-0503- 144-004).

After the exclusion of subjects with no or insufficient

DNA samples, 2 342 breast cancer patients with sufficient DNA samples were suitable to be genotyped. We excluded 198 patients who had a history of breast or other cancers, had benign breast cancers, or had no clinical pathological information. A total 421 patients who had missing followup duration and no information of chemotherapy were additionally excluded for the survival analysis. A final total of 1 721 incident breast cancer patients with genotypes remained. Among them, 1 338 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy, and 383 patients did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy.

A meta-analysis of reviewed studies was conducted in various cancer patients with chemotherapy. The associations of genetic variants with each outcome (PFS and OS) were estimated by summary hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Heterogeneity was evaluated by Q-test and I2 statistic. We used the fixed-effect model if I2 was <30% and P-value by Q-test was >0.05; otherwise, the random-effect model was used. If the SNPs included in the meta-analysis does not exist in the SEBCS, the highest correlated SNPs based on linkage disequilibrium (LD) on the Han Chinese from Beijing and Japanese from Tokyo (CHB + JPT) from the HapMap phase II database (release 22) were considered. If possible, subgroup analysis was performed by ethnicity, cancer site, study design, and regimen. The funnel plot and Egger’s test were carried out to detect the publication bias.

For SEBCS, we conducted SNP-based and gene-based analyses to investigate the association of transporter genes on breast cancer survival (DFS and OS). As the first step, SNP-based analysis was performed using multivariate Cox proportional hazard models in the additive genetic model. Violations of the proportional hazard assumption were assessed by Schoenfeld residuals test. We selected SNPs that had association at P-values < 0.001 among the patients who received chemotherapy. For the second step, genes that contain significant SNPs from the SNP-based results were further investigated by gene-based method based on an adaptive rank truncated product (ARTP) in a nested case-control study design, because the ARTP was not available for the survival analysis [24]. Patients who had no event (DFS and OS) were selected by frequencymatching based on follow-up duration (in 3 year strata) and age (in 10 year strata) as a 1:1 ratio. The ARTP method summarizes gene-level P-values as combining significant SNP-level P-values. SNPs with correlation r2 > 0.3 were removed in the gene-based analysis to avoid any associated signals for the genes caused by their top SNPs. P-values for gene-based analysis were estimated by 10,000 parametric permutation steps [25]. The P-values were corrected by the false discovery rate (FDR) based on the number of tested genes.

Outcomes for breast cancer survival

According to the retrospective medical record review, the outcomes in the cohort were defined as follows: DFS is defined as the time from the date of first breast cancer surgery to the date of recurrence, such as loco-regional recurrence, distant metastasis, contralateral recurrence, and any cause of death; OS is the time from the date of first breast cancer surgery to the date of death from any cause or last follow-up until December 2011 for censored patients.

Genotyping

A total of 453 ABC and SLC transporter genes were included in this study. We selected 49 ABC and 404 SLC transporter genes from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway and the Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB).

A total of 7,750 SNPs in the 453 ABC and SLC transporter genes were extracted from 555,117 genotyped SNPs in the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP array 6.0 chip (Affymetrix Inc.). Quality control measures were described

From the SEBCS results, LD structure of 34 SNPs in

ABCB1 was determined by using the Haploview 4.2 software (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, USA) [26]. Among 5 haplotype blocks, rs1045642 was correlated with

- J-E Kim et al.

- Associations between genetic polymorphisms of membrane transporter genes and prognosis after. . .

- J-E Kim et al.

Table 2 Summary of meta-analysis of survival after chemotherapy by genetic variation of ABCB1, ABCC2 and ABCG2

- Gene

- SNP

- Type of

survival

- Genetic model

- No. of

studies

- Summary HRs (95% CI)a

- P for

heterogeneity

I2

ABCB1

- rs1045642, C>Tb

- PFS

- Dominant

- 9

558553442244336555554334

1.33 1.04 0.94 1.11 0.96 0.98 1.07 1.00 1.08 1.13 1.30 0.96 1.06 0.71 0.74 1.17 0.96 0.95 1.17 0.91 1.06 0.84 1.19 0.98 1.00

(1.07–1.64) (0.89–1.21) (0.76–1.16) (0.89–1.40) (0.81–1.15) (0.77–1.23) (0.90–1.28) (0.80–1.24) (0.95–1.24) (0.71–1.82) (0.92–1.84) (0.74–1.24) (0.82–1.36) (0.41–1.23) (0.57–0.97) (0.84–1.63) (0.84–1.09) (0.83–1.08) (0.76–1.79) (0.75–1.11) (0.93–1.21) (0.69–1.02) (0.77–1.84) (0.73–1.32) (0.85–1.18)

0.046 0.448 0.783 0.070 0.668 0.282 0.540 0.020 0.139 0.698 0.792 0.194 0.143 0.041 0.305 0.002 0.558 0.676 0.090 0.591 0.328 0.477 0.058 0.040 0.405

49.3%

- 0.0%

- Heterozygote

Homozygote Dominant

0.0%

- OS

- 46.6%

- 0.0%

- Heterozygote

Homozygote Additive

20.8% 0.0% rs1045642, T>C

rs1128503, C>Tb rs2032582, G>T/A

PFS OS

Heterozygote Homozygote Heterozygote Homozygote Heterozygote Homozygote Heterozygote Homozygote Dominant

15.3% 49.3% 0.0% 0.0%

PFS

OS

36.3% 44.8% 68.6% 15.7% 74.4% 0.0%

PFS

Heterozygote Homozygote Dominant

0.0%

- OS

- 50.2%

- 0.0%

- Heterozygote

Homozygote Additive

13.5% 0.0%

ABCC2 ABCG2

rs717620, C>Tb rs2231137, G>Ab rs2231142, C>Ab

OS OS PFS OS

- Dominant

- 64.9%

69.0% 0.0%

Dominant Dominant

aSummary HRs (95% CI) were estimated by fixed-effect models if I2 was <30% and P for heterogeneity was >0.05; otherwise, the summary HRs (95% CIs) were estimated by random-effect models

bMeta-analysis was conducted to include the SEBCS

6 SNPs, rs1128503 was correlated with 11 SNPs and rs1202172 was correlated with 8 SNPs (r2 > 0.3). Three SNPs in block 4 of ABCB1 were considered to construct haplotypes, with two SNPs (rs4148738 (T>C, LD with rs1045642 (r2 = 0.516)), and rs10276036 (C>T, LD with rs1128503 (r2 = 1)) shown significant results from metaanalysis and one SNP (rs1202172 (A>C)) shown significant results from SEBCS (Supplementary Figure 1). After excluding the missing genotype with at least one of three polymorphic sites, individual haplotypes were estimated by using the PHASE program version 2.1 [27]. The hazard of breast cancer survival was estimated by each haplotype compared with the haplotype containing all the major alleles as a reference. Based on the haplotype results, the diplotype (combination of haplotype) analysis was conducted to assess effects by the increased number of risk haplotype. All analyses of SEBCS were adjusted for age, tumor size, node status and metastasis (TNM) stage, and subtype based on estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). Patients with TNM stage IV were excluded for the association of DFS.

We evaluated the interaction of the SNPs and chemotherapy by the likelihood ratio test comparing models with and without an interaction terms. Among patients who received chemotherapy, a subgroup analysis was performed by prescribed regimen (anthracycline, CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil), and taxane) and additionally adjusted for other regimen types that were not considered as a stratification factor.

Statistical analysis was performed by PLINK software

version 1.07 (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/), “ARTP2”,

“GenABEL” and “meta” packages in R version 3.3.2 (the R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and SAS statistical software package version 9.4 (SAS Institute., Cary, NC, USA).

Associations between genetic polymorphisms of membrane transporter genes and prognosis after. . .

Most studies included Asian patients (n = 19). Most of the studies were conducted for lung cancer (n = 16), and 4 studies were conducted among breast cancer patients. The number of patients varied within a range from 53 to 973 patients. Most studies included ABCB1 (n = 22), with 8 and 7 studies including ABCC2 and ABCG2, respectively. The summary of the included studies from a systematic review is identified in Supplementary Table 1. Considering the number of studies that can be analyzed based on outcomes and genetic models, the meta-analysis was conducted on three ABC genes.

Table 2 shows that the meta-analysis in both PFS and OS was conducted by genetic variations of ABCB1, ABCC2, and ABCG2. The SEBCS was included as a study in the meta-analysis of ABCB1 (rs6949448 in LD with rs1045642 (r2 = 0.618), rs10276036 in LD with rs1128503 (r2 = 1)), ABCG2 (rs4148152 in LD with 2231137 (r2 = 1), rs1481012 in LD with rs23231142 (r2 = 1)) and ABCC2 (rs717620). The results of the meta-analysis in the dominant model showed that rs1045642 (C>T) in ABCB1 (HR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.07–1.64) was associated with poor PFS, especially in Asian patients (HR = 1.56, 95% CI: 1.07–2.27) and stomach cancer (HR = 1.88, 95% CI: 1.14–3.10). When stratified by study design, the association of rs1045642 with PFS was significant in observational studies (HR = 1.28, 95% CI: 1.05–1.56), but not significant in clinical trials (HR = 1.47, 95% CI: 0.96–2.27) (Fig. 2). The funnel plot and Egger’s test (P = 0.142) suggested no evidence of publication bias of included studies (Supplementary Figure 2). In the codominant model, homozygotes of rs1128503 (C > T) in ABCB1 was associated with longer overall survival (HR = 0.74, 95% CI: 0.57–0.97). However, there was no significant association between ethnicity. The funnel plot and Egger’s test (P = 0.520) suggested no evidence of publication bias of included studies. There was no significant association with survival in either ABCC2 or ABCG2. The result of meta-analysis limited to breast cancer indicated that ABCB1 rs2032582 (G>T/A) was not significant association with OS (HR = 2.03, 95% CI: 0.53–7.84).

In SEBCS, 195 patients relapsed, and 108 patients died during follow-up duration among 1 338 patients who received chemotherapy. Both the characteristics of patients in the total cohort study for SNP-based analysis and in the nested case-control study for gene-based analysis showed similar patterns of significant association of TNM stage and tumor subtype on DFS and OS (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 2). In the 383 patients who did not receive chemotherapy, 23 patients relapsed, and 9 patients died during follow-up duration (Supplementary Table 3).