“Birkenhead Diner,” G.W.R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hazel Grove & District Model Railway Society Annual Exhibition – October

Hazel Grove & District Model Railway Society Annual Exhibition – October 2013 Chairman’s Welcome I’m delighted to welcome you to this, our 39th Exhibition. I’m sure that you will find much of interest in the layouts on display as well as opportunities to buy that elusive item or tool from the Traders who help to support our hobby. I would like to thank all our advertisers for their support and hope you can enjoy their services in the future. Also the staff of the leisure centre who give us tremendous support in staging the event. If, after your visit, we have stirred your appetite and you would like to visit or join us, please enquire at the club information desk for further details. Late news! Exhibition Special Membership Offer Join our Club during the October Exhibition and get your entrance fee to the Exhibition refunded! Phil Pugh, Chairman From The Exhibition Committee We hope you enjoy the exhibition and the variety of layouts on show. The traders have, between them, a huge selection of items for the enthusiast and also for modellers in general – especially tools and materials. Please ask if your requirements are not on display as many of them have mail order facilities. Some are local for you to visit after the show. This year we have caterers providing refreshments. Just the place to relax and chat in an area close to the centres pay desk – look for the signs. Thank you also to the members of the Manchester Transport Museum for their time to provide us with and drive the courtesy bus. -

Framework Capacity Statement

Framework Capacity Statement Network Rail December 2016 Network Rail Framework Capacity Statement December 2016 1 Contents 1. Purpose 1.1 Purpose 4 2. National overview 2.1 Infrastructure covered by this statement 6 2.2 Framework agreements in Great Britain 7 2.3 Capacity allocation in Great Britain 9 2.4 National capacity overview – who operates where 10 2.5 National capacity overview – who operates when 16 3. Network Rail’s Routes 3.1 Anglia Route 19 3.2 London North East & East Midlands Route 20 3.3 London North Western Route 22 3.4 Scotland Route 24 3.5 South East Route 25 3.6 Wales Routes 27 3.7 Wessex Route 28 3.8 Western Route 29 4. Sub-route and cross-route data 4.1 Strategic Routes / Strategic Route Sections 31 4.2 Constant Traffic Sections 36 Annex: consultation on alternative approaches A.1 Questions of interpretation of the requirement 39 A.2 Potential solutions 40 A.3 Questions for stakeholders 40 Network Rail Framework Capacity Statement December 2016 2 1. Purpose Network Rail Framework Capacity Statement December 2016 3 1.1 Purpose the form in which data may be presented. The contracts containing the access rights are publicly available elsewhere, and links are provided in This statement is published alongside Network Rail’s Network Statement section 2.2. However, the way in which the rights are described when in order to meet the requirements of European Commission Implementing combined on the geography of the railway network, and over time, to meet Regulation (EU) 2016/545 of 7 April 2016 on procedures and criteria the requirements of the regulation, is open to some interpretation. -

Part 3 of the Bibliography Catalogue

Bibliography - L&NWR Society Periodicals Part 3 - Railway Magazine Registered Charity - L&NWRSociety No. 1110210 Copyright LNWR Society 2012 Title Year Volume Page Railway Magazine Photos. Junction at Craven Arms Photos. Tyne-Mersey Power. Lime Street, Diggle 138 Why and Wherefore. Soho Road station 465 Recent Work by British Express Locomotives Inc. Photo. 2-4-0 No.419 Zillah 1897 01/07 20 Some Racing Runs and Trial Trips. 1. The Race to Edinburgh 1888 - The Last Day 1897 01/07 39 What Our Railways are Doing. Presentation to F.Harrison from Guards 1897 01/07 90 What Our Railways are Doing. Trains over 50 mph 1897 01/07 90 Pertinent Paragraphs. Jubilee of 'Cornwall' 1897 01/07 94 Engine Drivers and their Duties by C.J.Bowen Cooke. Describes Rugby with photos at the 1897 01/08 113 Photo.shed. 'Queen Empress' on corridor dining train 1897 01/08 133 Some Railway Myths. Inc The Bloomers, with photo and Precedent 1897 01/08 160 Petroleum Fuel for Locomotives. Inc 0-4-0WT photo. 1897 01/08 170 What The Railways are Doing. Services to Greenore. 1897 01/08 183 Pertinent Paragraphs. 'Jubilee' class 1897 01/08 187 Pertinent Paragraphs. List of 100 mile runs without a stop 1897 01/08 190 Interview Sir F.Harrison. Gen.Manager .Inc photos F.Harrison, Lord Stalbridge,F.Ree, 1897 01/09 193 TheR.Turnbull Euston Audit Office. J.Partington Chief of Audit Dept.LNW. Inc photos. 1897 01/09 245 24 Hours at a Railway Junction. Willesden (V.L.Whitchurch) 1897 01/09 263 What The Railways are Doing. -

Third Party Funding

THIRD PARTY FUNDING IS WORKING IAN BAXTER, Strategy Director at SLC Rail, cheers enterprising local authorities and other third parties making things happen on Britain’s complex railway n 20 January 1961, John F. Kennedy used being delivered as central government seeks be up to them to lead change, work out how his inaugural speech as US President more external investment in the railway. to deliver it and lever in external investment Oto encourage a change in the way of into the railway. It is no longer safe to assume thinking of the citizens he was to serve. ‘Ask DEVOLUTION that central government, Network Rail or not what your country can do for you,’ intoned So, the theme today is: ‘Ask not what the train operators will do this for them. JFK, ‘but what you can do for your country.’ the railway can do for you but what However, it hardly needs to be said, least of Such a radical suggestion neatly sums up you can do for the railway’. all to those newly empowered local railway the similar change of approach represented Central government will sponsor, develop, promoters themselves, enthusiastic or sceptical, collectively by the Department for Transport’s fund and deliver strategic railway projects that the railway is a complex entity. That March 2018 ‘Rail Network Enhancements required for UK plc, such as High Speed 2, applies not only in its geographical reach, Pipeline’ (RNEP) process, Network Rail’s ‘Open for electrification, long-distance rolling stock scale and infrastructure, but also in its regularly Business’ initiative and the ongoing progress of replacement or regeneration at major stations reviewed post-privatisation organisation, often devolution of railway planning and investment like London Bridge, Reading or Birmingham New competing or contradictory objectives, multiple to the Scottish and Welsh governments, Street. -

Integrated Coaching Management System in Indian Railways

Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Integrated Coaching Management System in Indian Railways for the year ended March 2016 Laid in Lok Sabha/Rajya Sabha on ___________ Union Government (Railways) Report No.32 of 2016 PREFACE This Report has been prepared for submission to the President of India under Article 151 of the Constitution of India. This Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India contains the results of the ITAudit of Integrated Coaching Management System in Indian Railways. The instances mentioned in this Report are those which came to the notice during course of test audit during the year 2015-16. Matters to the period prior to April 2015 and after March 2016 have also been included wherever necessary. The audit has been conducted in conformity with the Auditing Standards issued by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India. Audit wishes to acknowledge the co-operation received from Ministry of Railways at each stage of the audit process. CONTENTS Paragraph Pages Abbreviations used in the Report i Executive Summary iii to vi Chapter1 Introduction Modules of ICMS 1.1 1 Objectives of the ICMS 1.2 2 System Architecture 1.3 2 Organization 1.4 2 Audit Objectives 1.5 3 Audit Criteria 1.6 3 Audit Methodology and Scope 1.7 3 Sample size 1.8 4 Acknowledgement 1.9 4 Chapter 2 Achievement of objectives of ICMS Monitoring punctuality of trains through ICMS 2.1 5 Monitoring status of coaching stock through ICMS 2.2 10 Managing coach maintenance through ICMS 2.3 18 Chapter 3 Application Controls Deficiencies in integration between ICMS and other 3.1 22 applications viz. -

Donkey 115 Dec 06

Contents: Edition 100 Years of the Joint Line - Part 3 115 Real Steam is Alive in Africa December 2006 Spirited Away The Magazine of the Marlow & District Railway Society President: Sir William McAlpine Bt Chairman: Tim Speechley. 11 Rydal Way, High Wycombe, Bucks., HP12 4NS. Tel.: 01494 638090 email: [email protected] Vice-Chairman Julian Heard. 58 Chalklands, Bourne End, Bucks., SL8 5TJ. Tel.: 01628 527005 email: [email protected] Treasurer: Peter Robins. 95 Broome Hill, Cookham, Berks., SL6 9LJ. Tel.: 01628 527870 email: [email protected] Secretary: Malcolm Margetts. 4 Lodge Close, Marlow, Bucks., SL7 1RB. Tel.: 01628 486433 email: [email protected] Webmaster: Tim Edmonds. 90 Green Hill, High Wycombe, Bucks., HP13 5QE. Tel.: 01494 526346 email: [email protected] Committee: Roger Bowen. 10 Cresswell Way, Holmer Green, High Wycombe, Bucks., HP15 6TE Tel.: 01494 713887 email: [email protected] Outings Organiser: Mike Hyde. 11 Forty Green Drive, Marlow, Bucks., SL7 2JX. Tel.: 01628 485474 email: [email protected] Donkey Editor: Mike Walker, Solgarth, Marlow Road, Little Marlow, Marlow, Bucks., SL7 3RS. Tel.: 01628 483899 email: [email protected] Website: www.mdrs.org.uk TIMETABLE - Forthcoming meetings Page 2 CHAIRMAN'S NOTES Tim Speechley 2 SOCIETY & LOCAL NEWS 3 AUTUMN HIGHLANDER Mike Hyde 4 100 YEARS OF THE JOINT LINE Part 3 Mike Walker 5 REAL STEAM IS ALIVE IN AFRICA Dave Theobald 9 25 AND !% YEARS AGO Tim Edmonds 13 SPIRITED AWAY Gordon Rippington 15 FRONT COVER PHOTOGRAPHS Top: 45533 ‘Lord Rathmore’ on Bushey troughs May 1960 Photo: Ken Lawrie. -

West Midlands and Chilterns Route Utilisation Strategy Draft for Consultation Contents 3 Foreword 4 Executive Summary 9 1

November 2010 West Midlands and Chilterns Route Utilisation Strategy Draft for Consultation Contents 3 Foreword 4 Executive summary 9 1. Background 11 2. Dimensions 20 3. Current capacity, demand, and delivery 59 4. Planned changes to infrastructure and services 72 5. Planning context and future demand 90 6. Gaps and options 149 7. Emerging strategy and longer-term vision 156 8. Stakeholder consultation 157 Appendix A 172 Appendix B 178 Glossary Foreword Regional economies rely on investment in transport infrastructure to sustain economic growth. With the nation’s finances severely constrained, between Birmingham and London Marylebone, as any future investment in transport infrastructure well as new journey opportunities between Oxford will have to demonstrate that it can deliver real and London. benefits for the economy, people’s quality of life, This RUS predicts that overall passenger demand in and the environment. the region will increase by 32 per cent over the next 10 This draft Route Utilisation Strategy (RUS) sets years. While Network Rail’s Delivery Plan for Control out the priorities for rail investment in the West Period 4 will accommodate much of this demand up Midlands area and the Chiltern route between to 2019, this RUS does identify gaps and recommends Birmingham and London Marylebone for the next measures to address these. 30 years. We believe that the options recommended Where the RUS has identified requirements for can meet the increased demand forecast by this interventions to be made, it seeks to do so by making RUS for both passenger and freight markets and the most efficient use of capacity. -

LNW Route Specification 2017

Delivering a better railway for a better Britain Route Specifications 2017 London North Western London North Western July 2017 Network Rail – Route Specifications: London North Western 02 SRS H.44 Roses Line and Branches (including Preston 85 Route H: Cross-Pennine, Yorkshire & Humber and - Ormskirk and Blackburn - Hellifield North West (North West section) SRS H.45 Chester/Ellesmere Port - Warrington Bank Quay 89 SRS H.05 North Transpennine: Leeds - Guide Bridge 4 SRS H.46 Blackpool South Branch 92 SRS H.10 Manchester Victoria - Mirfield (via Rochdale)/ 8 SRS H.98/H.99 Freight Trunk/Other Freight Routes 95 SRS N.07 Weaver Junction to Liverpool South Parkway 196 Stalybridge Route M: West Midlands and Chilterns SRS N.08 Norton Bridge/Colwich Junction to Cheadle 199 SRS H.17 South Transpennine: Dore - Hazel Grove 12 Hulme Route Map 106 SRS H.22 Manchester Piccadilly - Crewe 16 SRS N.09 Crewe to Kidsgrove 204 M1 and M12 London Marylebone to Birmingham Snow Hill 107 SRS H.23 Manchester Piccadilly - Deansgate 19 SRS N.10 Watford Junction to St Albans Abbey 207 M2, M3 and M4 Aylesbury lines 111 SRS H.24 Deansgate - Liverpool South Parkway 22 SRS N.11 Euston to Watford Junction (DC Lines) 210 M5 Rugby to Birmingham New Street 115 SRS H.25 Liverpool Lime Street - Liverpool South Parkway 25 SRS N.12 Bletchley to Bedford 214 M6 and M7 Stafford and Wolverhampton 119 SRS H.26 North Transpennine: Manchester Piccadilly - 28 SRS N.13 Crewe to Chester 218 M8, M9, M19 and M21 Cross City Souh lines 123 Guide Bridge SRS N.99 Freight lines 221 M10 ad M22 -

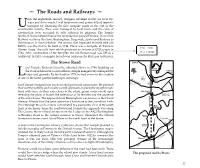

The Roads and Railways

The Roads and Railways ntil the eighteenth century, villagers travelled slowly on local by- ways and drove roads. Local landowners and gentry helped improve Utransport by financing the first turnpike roads at the end of the seventeenth century. They were managed by local trusts and the costs of construction were recouped by tolls collected by pikemen. The Temple family of Stowe helped finance the turnpike that passed Finmere. It ran from Bedford via Stony Stratford, Buckingham, Tingewick, Aynho and Banbury to Warmington in Warwickshire. The section that bypassed Finmere (the old B4031) was the first to be built in 1744. There was a turnpike at ‘Finmere 1784 2000 Warren Gates,’ the tolls from which produced an income of £253 a year in 1784. After construction of the turnpike, the old Roman road was left as a £253 £20,000 bridleway. In 1813, a turnpike branch was laid from the Red Lion to Bicester. The Stowe Road Dadford ord Temple, Richard Grenville, inherited Stowe in 1749. Building on Stowe House Corinthian the work of his uncle, Lord Cobham, Temple energetically reshaped the Arch Oxford Avenue Lhouse and grounds. By his death in 1779, he had overseen the creation NORTH Boycott of one of the finest garden landscapes in Europe. Welsh Oxford Manor Water To Lan Biddenham e The Lord Temple’s magnificent estate needed good road connections. He planned Course that visiting nobility and royalty would approach on perfectly straight roads Water Stratford lined with trees. As they rode closer to the estate, grand vistas would open Lodge Buffler's Holt revealing the glory of Stowe, the splendour of its temples and the opulence (Robin Hood) of the main house. -

Rolling Stock: Locomotives and Rail Cars

Rolling Stock: Locomotives and Rail Cars Industry & Trade Summary Office of Industries Publication ITS-08 March 2011 Control No. 2011001 UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMISSION Karen Laney Acting Director of Operations Michael Anderson Acting Director, Office of Industries This report was principally prepared by: Peder Andersen, Office of Industries [email protected] With supporting assistance from: Monica Reed, Office of Industries Wanda Tolson, Office of Industries Under the direction of: Deborah McNay, Acting Chief Advanced Technology and Machinery Division Cover photo: Courtesy of BNSF Railway Co. Address all communication to Secretary to the Commission United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 www.usitc.gov Preface The United States International Trade Commission (USITC) has initiated its current Industry and Trade Summary series of reports to provide information on the rapidly evolving trade and competitive situation of the thousands of products imported into and exported from the United States. Over the past 20 years, U.S. international trade in goods and services has risen by almost 350 percent, compared to an increase of 180 percent in the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP), before falling sharply in late 2008 and 2009 due to the economic downturn. During the same two decades, international supply chains have become more global and competition has increased. Each Industry and Trade Summary addresses a different commodity or industry and contains information on trends in consumption, production, and trade, as well as an analysis of factors affecting industry trends and competitiveness in domestic and foreign markets. This report on the railway rolling stock industry primarily covers the period from 2004 to 2009, and includes data for 2010 where available. -

REPORT of SURVEY 1 Progress in Railway Mechanical Engineering, 1967-1968

REPORT OF SURVEY 1 Progress in Railway Mechanical Engineering, 1967-1968 Introduction the side post, and floor stringers are made of high density poly- urethane [3]. DEVELOPMENTS in the carbuilding field continued at a Pullman-Standard has developed an atmosphere control sys- brisk pace even though there was a sharp decline in the purchasing tem (Figs. 5 and 6) which will both refrigerate and control the of uew equipment by the railroad industry. The trend to pro- oxygen content of the environmental air in an insulated railroad duce specialized equipment designed to help the consignor and car. The Pullman-Standard system combines nitrogen storage Downloaded from http://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/manufacturingscience/article-pdf/91/3/817/6499103/817_1.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 consignee in the loading and unloading of a specific commodity tanks, spray headers, and temperature sensing, and control equip- continues to dominate the development of new equipment. As ment, which are standard components of Linde's "Polarstream" the users of the railroad's service continue to approach their system with Pullman-Standard's specified orifice, heat exchanger, physical distribution problems on a total cost basis, this trend air motor, and fan to achieve the desired temperature and atmo- toward specialized equipment can be expected to continue, and spheric condition within the lading area. The sj'stem operates perhaps accelerate, in the near future. by releasing liquid nitrogen into the lading area. The nitrogen instantly vaporizes and absorbs heat in the lading air space. The orifice draws in outside air to maintain the desired oxygen New Freight Cars percentages in the lading area. -

Forward Crossword …………………..………………………………………………………………

Journal of the Great Central Railway Society No. 154 December 2007 Front cover caption BR class C13 4-4-2T no. 67416 at Chesham with the branch push-pull service from Chalfont in the 1950s. The locomotive was built in 1903 as GCR class 9K and survived until 1958. The ex- Metropolitan Railway stock used on this service (built by Ashbury of Manchester) has been the subject of an award-winning restoration project on the Bluebell Railway. Photo: E. D. Thomas The Journal of the Great Central Railway Society No. 154 ~ December 2007 Contents Editorial by Bob Gellatly …………………………………………………………………….………….. 2 The Wombwell accident of 1911 by Jim Thompson .……………………………….……. 4 Len's Stratford-on-Avon & Midland Joint (part 2) bus trip by Ken Grainger… 8 The Knightsbridge connection by Michael Minter Taylor…………………………….... 12 The LNER Study Group symposium…………………………………………………….………. 13 Sheffield Victoria through the lens of 'loose grip 99' photo feature………..… 14 Demolition of Staveley Central by Chris Booth …………………………………………… 15 Sale of books by Colin Walker ………………………………………………………..…..……. 18 On Great Central lines today by Kim Collinson….…..……………………….….….……... 19 Caption feedback on Whitworth photos at Guide Bridge ………………….…….. 20 Members and their models – 'A Robinson 0-8-4T ' by Geoff Burton ………..…. 21 The GCRS Autumn Meeting at Ruddington by Paul White ..…………….……..….. 22 Locomotive performance in the declining days of the GCR route an article by John F. Clay from 'The Railway Observer' of June 1964 …………………. 27 The fall and rise of the GC main line by Dennis Wilcock …………………...…………. 33 Forward crossword …………………..……………………………………………………………….. 36 The Warsop Curve dispute of 1908 by Bill Taylor ………………………………………… 37 Readers forum …………………………………………………………………….……………………… 40 back Meetings diary …………………………………………………………………………………………… cover - 1 - Editorial by Bob Gellatly I have been told by one GCRS member that the editorial in the last issue had made him feel depressed.